Thesis-2001-P115f.Pdf (9.583Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arkansas History (Spring Semester)

Year At A Glance 2019-2020 Central High School Social Studies Department Subject: Arkansas History (Spring Semester) Major Concept/Topic Chapter(s)/Pages Standards Quarter 3 Arkansas Today/Arkansas Land Regions Chapter 1: A Land Called G.1.AH.7-8.1 Compare and January 7-- Arkansas, Land of Abundant contrast the six geographic March 13 Waters, Arkansas’s Natural regions of Arkansas using (9weeks) Ecosystems, Physical and geographic representations and Cultural Geography, Climate: available geospatial Geography in Motion technologies. Pages: 4-30 G.1.AH.7-8.2 Analyze the availability of resources and their effects on the development of each geographic region of the state (e.g., diamonds, bauxite, oil, timber, agricultural, wild game). G.1.AH.7-8.3 Evaluate the reciprocal impact of humans and water systems in Arkansas over time (e.g., trade, transportation, recreation, flood control). G.1.AH.7-8.4 Analyze effects of weather, climate, and natural phenomena on the environment of specific regions over time (e.g., New Madrid earthquakes, Flood of 1927, Drought of 1930, tornado alley). Early Arkansas Chapter 2: Two Worlds H.7.AH.7-8.1 Evaluate ways that Meet: historical events in Arkansas Archaeology and the Earliest were shaped by circumstances in Arkansans, From time and place. Mississippian to Modern, The Spanish Arrive, The French Settle Pages: 36-66. G.2.AH.7-8.3 Examine ways the geography of Arkansas affected cultural characteristics of places and regions. Frontier Arkansas Chapter 3: Americans Settle G.2.AH.7-8.1 Analyze the impact Arkansas: The Louisiana of geography on settlement and Purchase, Frontier Arkansas movement patterns over time using geographic representations and a variety of primary and secondary sources (e.g., Louisiana Purchase survey, westward movement, voluntary and involuntary migration and immigration). -

Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings - Volume 8 1955 Academy Editors

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 8 Article 1 1955 Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings - Volume 8 1955 Academy Editors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Recommended Citation Editors, Academy (1955) "Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings - Volume 8 1955," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 8 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol8/iss1/1 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Entire Issue is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 8 [1955], Art. 1 ARKANSAS ACADEMY OF SCIENCE Founded 1917 proceedings Volume Vni 195? Published by Arkansas Academy of Science, 1955 107 Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 8 [1955], Art. 1 CONTENTS —VOLUME VIII --------------------- Program of 38th Annual Meeting --------------- iQg Secretary's Report of 38th Annual Meeting ---------- Abstracts of Papers Presented at 38th Annual Meeting ------ nj Cowpea and Bean Weevils. W. D. Wylie 13n Cationic Activities and the Exchange Phenomena of Plant Roots; Relationship to Practical Problems of Nutrient--- Uptake. -

Case 4:15-Cv-00784-KGB Document 142 Filed 07/02/18 Page 1 of 148

Case 4:15-cv-00784-KGB Document 142 Filed 07/02/18 Page 1 of 148 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS WESTERN DIVISION PLANNED PARENTHOOD ARKANSAS and EASTERN OKLAHOMA, d/b/a PLANNED PARENTHOOD OF THE HEARTLAND; and STEPHANIE HO, M.D., on behalf of themselves and their patients PLAINTIFFS v. Case No. 4:15-cv-00784-KGB LARRY JEGLEY, Prosecuting Attorney for Pulaski County, in his official capacity, his agents and successors; and MATT DURRETT, Prosecuting Attorney for Washington County, in his official capacity, his agents and successors DEFENDANTS PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION ORDER Before the Court is the second motion for preliminary injunction filed by plaintiffs Planned Parenthood of Arkansas and Eastern Oklahoma, d/b/a Planned Parenthood of the Heartland (“PPAEO”), and Stephanie Ho, M.D., on behalf of themselves and their patients (Dkt. No. 116). Plaintiffs bring this action seeking declaratory and injunctive relief on behalf of themselves and their patients under the United States Constitution and 42 U.S.C. § 1983 to challenge Section 1504(d) of the Abortion-Inducing Drugs Safety Act, 2015 Arkansas Acts 577 (2015) (“Section 1504(d),” “the Act,” or “the contracted physician requirement”), codified at Arkansas Code Annotated § 20-16-1501 et seq. This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343(a)(3). Defendants Larry Jegley, prosecuting attorney for Pulaski County, in his official capacity, his agents and successors, and Matt Durrett, prosecuting attorney for Washington County, in his official capacity, his agents and successors, responded in opposition to the motion (Dkt. No. -

Graduate Bulletin and Become Completely Familiar with the Organization and the Regulations of the University

STUDENT RESPONSIBILITY Each student should study this Graduate Bulletin and become completely familiar with the organization and the regulations of the university. Failure to do this may result in serious mistakes for which the student shall be held fully responsible. POLICY STATEMENT Policies and procedures stated in this bulletin—from admission through graduation—require continuing evaluation, review, and approval by appropriate university officials. All statements reflect policies in existence at the time this bulletin went to press, and the university reserves the right to change policies at any time and without prior notice. University officials determine whether students have satisfactorily met admission, retention, or graduation requirements. Arkansas State University reserves the right to require a student to withdraw from the university for cause at any time. EQUAL OPPORTUNITY/AFFIRMATIVE ACTION Arkansas State University is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer with a strong institutional commitment to the achievement of excellence and diversity among its faculty and staff. To that end, the University provides opportunities in employment practices, admission and treatment of students without regard to race, color, religion, age, disability, gender, national origin, or veteran status. ASU complies with all applicable federal and state legislation and does not discriminate on the basis of any unlawful criteria. Questions regarding this policy should be addressed to the Affirmative Action Program Coordinator, P.O. Box 1500, State University, Arkansas 72467. Telephone (870) 972-3658. SERVICES FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES Arkansas State University's Coordinator of Services to students, faculty and staff with dis- abilities is also the university's compliance coordinator for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the ADA Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG). -

The Usage and Perceptions of Swamps by African-Americans in Antebellum and Postbellum Arkansas and Louisiana" (2014)

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2014 From swamps to swamping: The su age and perceptions of swamps by African-Americans in Antebellum and Postbellum Arkansas and Louisiana Tessa Annette Neblett vE ans James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Tessa Annette Neblett, "From swamps to swamping: The usage and perceptions of swamps by African-Americans in Antebellum and Postbellum Arkansas and Louisiana" (2014). Masters Theses. 196. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/196 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Swamps to Swamping: The Usage and Perceptions of Swamps by African-Americans in Antebellum and Postbellum Arkansas and Louisiana Tessa Annette Neblett Evans A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2014 DEDICATION To my family ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was greatly aided by the members of my committee, including the director, Dr. Andrew Witmer, who helped me throughout the entire process of researching and writing this thesis. He helped me to narrow my focus and gave me advice regarding historical frameworks that would help to clarify and organize this project. I also wish to thank Dr. Lanier, because she introduced me to cultural geography and landscape studies, and her advice and book suggestions helped me to organize and think about this project in many different ways. -

Arkansas History Grades 7-8 Social Studies Curriculum Framework Arkansas Department of Education Revised 2014

Arkansas History Grades 7-8 Social Studies Curriculum Framework Revised 2014 Arkansas History Grades 7-8 Course Focus and Content In Grades K-6, students receive a foundation in Arkansas History. Arkansas History Grades 7-8 is an in-depth and rigorous study of civics/government, economics, geography, and history of the state. The format of this course encourages teachers to incorporate the social, cultural, and geographic information particular to their locality when developing district curriculum. Skills and Application Throughout the course, students will develop and apply disciplinary literacy skills: reading, writing, speaking, and listening. As students seek answers to compelling and supporting questions, they will examine a variety of primary and secondary sources and communicate responses in multiple ways, including oral, visual, and written forms. Students must be able to select and evaluate sources of information, draw and build upon ideas, explore issues, examine data, and analyze events from the full range of human experience to develop critical thinking skills essential for productive citizens. Arkansas History is required by Act 787 of 1997 and the Standards for Accreditation and does not need Arkansas Department of Education approval. The acquisition of content knowledge and skills is paramount in a robust social studies program rooted in inquiry. The chart below summarizes social studies practices in Dimensions 1, 3, and 4 of The College, Career, & Civic Life C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards. These practices should be addressed throughout Grades K-12, building as students acquire the skills. Dimension 2 sets forth the conceptual content, and the alignment to this dimension is embedded in the student learning expectations (SLEs). -

Southern Arkansas Studies

Southern & INTERDISCIPLINARY Arkansas Studies (21 hours total required) MINOR ! Core IN (9 hours required) select from the followinG courses: SOUTHERN AND ENGL 4362 Southern Literature & Folklore HIST 4345 The South to 1865 RKANSAS TUDIES HIST 4346 The South since 1865 A S HIST 4355 The Role of Arkansas in the Nation GEOG 3380 Geography in Arkansas PSCI 3336 Local Government & Politics ANTH 3300 Regional Anthropology (when Ozarks is the topic) ! Electives (9 hours required) select from the remaining core courses above and/or from the following: ENGL 4380 African & African-American Literature ENGL 4382 Race in American Literature (when southern writers are the focus) HIST 3353 African- American History to 1868 HIST 3354 African-American History since 1868 HIST 4330 Civil War & Reconstruction ANTH 3315 Native American Cultures In consultation with the minor advisor, students may substitute appropriate courses from any department for one !of the electives listed above. ! Capstone Course (3 hours required) Dr. Story Matkin-Rawn selected from the following: Coordinator, Independent study: Research project to be Southern & Arkansas supervised by faculty of student's choice Studies Minor Internship: Internship approved by coordinator in consultation with the student Department of History UNIVERSITY Students seeking to continue the minor must meet with the Irby Hall 417 coordinator the semester before finishing the program in 501.450.5630 OF order to set up the independent study or internship. CENTRAL ARKANSAS Interdisciplinary Minor in Southern and Arkansas Studies GOAL OF THIS PROGRAM The Interdisciplinary Minor in Southern and Arkansas Studies provides undergraduates with an opportunity to broaden their understanding of the unique culture, politics, history, and geography of Arkansas and the South. -

EXPEDITION Exploring the Louisiana Purchase and Its Impact on Arkansas

The GRE AT EXPEDITION Exploring the Louisiana Purchase and Its Impact on Arkansas Arts + Humanities Arkansas Sponsored by the Quapaw Tribe ABOUT FUSION: ARTS + HUMANITIES ARKANSAS Fusion: Arts + Humanities Arkansas is an educational program designed to enrich the teaching of our state’s heritage and culture and celebrate our human achievement through programs in history, literature, philosophy, civics, and other disciplines. To achieve these goals, the Clinton Presidential Center convenes cultural institutions, historians, and community organizations to plan and execute an annual Fusion program featuring a series of symposia and an exhibition highlighting one theme from Arkansas’s history and culture. The 2018 Fusion: Arts + Humanities Arkansas program is entitled Exploring the Louisiana Purchase and Its Impact on Arkansas. The Louisiana Purchase is the largest land acquisition in American history. It doubled the size of the United States and included all or part of 15 present-day U.S. states – including the entire state of Arkansas – and parts of two Canadian provinces. The 2018 Fusion program features conversations with historians and authors on the subject, an Acadian-Creole musical performance, and period-appropriate reenactors participating in-character. It is designed to bring a new perspective of the history of the Louisiana Purchase to the classroom. The Great Expedition: Exploring the Louisiana Purchase and Its Impact on Arkansas highlights the domestic and international importance of the Louisiana Purchase and also tells the story of what became known as The Great Expedition, led by William Dunbar and George Hunter through present-day northern Louisiana and southern Arkansas. The exhibit includes three original Louisiana Purchase Treaty documents from the National Archives and Records Administration. -

VITA HUBERT B. STROUD Mailing Address

VITA HUBERT B. STROUD Mailing Address P. O. Box 2410 State University, Arkansas 72467 (870) 972-3125 Home Address 1900 MacArthur Park Jonesboro, Arkansas 72401 (870) 935-4791 Date/Place of Birth September 7, 1944 Springfield, Tennessee Marital Status Married, one child Education B.S. Geography Austin Peay State University 1966 M.A. Geography Memphis State University 1968 Thesis Title: "Land Use in Robertson County, Tennessee." Ph.D. Geography University of Tennessee 1974 Dissertation Title: "Amenity Land Developments as an Element of Geographic Change: A Case Study, Cumberland County, Tennessee." Committee: Theodore H. Schmudde (Chairman) Edwin H. Hammond, John Rehder, William Cole Areas of Expertise Teaching Introduction to Geography Physical Geography Resource Management (Conservation and Water Resources) Climatology Research Amenity Land Developments Water Resources Planning Problems Associated with Pre-Platted Communities Rural and Recreational Land Use HUBERT B. STROUD/Vita, continued 2 Professional Organizations: American Planning Association Association of American Geographers Southwest Division, Association of American Geographers Southeast Division, Association of American Geographers Arkansas Geographical Society Gamma Theta Upsilon National Geographic Society Audubon Society Teaching Experience: 1985 – Present Professor of Geography Arkansas State University 1978 – 1985 Associate Professor of Geography Arkansas State University 1974 – 1978 Assistant Professor of Geography Arkansas State University 1971 – 1973 Teaching Assistant -

38Th Annual Meeting, 1954. Program Academy Editors

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 8 Article 3 1955 38th Annual Meeting, 1954. Program Academy Editors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Education Commons, Engineering Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Editors, Academy (1955) "38th Annual Meeting, 1954. Program," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 8 , Article 3. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol8/iss1/3 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Arkansas Academy Annual Meeting report is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 8 [1955], Art. 3 ARKANSAS ACADEMY OF SCIENCE Thirty-Ei gh th Annual Meeting University of Arkansas, Fayetteville April 23-24, 1954 Friday, April 23 9:00 a.m. Registration 11:00 a.m. Meeting Called to Order, Dr. Z. V. Harvalik presiding. Welcoming address by Mayor Roy Scott of the City of Fayetteville, and Dr. Joe E. -

Here's the Judge's 100-Page Ruling

Case 4:15-cv-00784-KGB Document 114 Filed 06/18/18 Page 1 of 100 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS WESTERN DIVISION PLANNED PARENTHOOD ARKANSAS & EASTERN OKLAHOMA, d/b/a PLANNED PARENTHOOD OF THE HEARTLAND; and STEPHANIE HO, M.D., on behalf of themselves and their patients PLAINTIFFS v. Case No. 4:15-cv-00784-KGB LARRY JEGLEY, Prosecuting Attorney for Pulaski County, in his official capacity, his agents and successors; and MATT DURRETT, Prosecuting Attorney for Washington County, in his official capacity, his agents and successors DEFENDANTS TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER Before the Court is the renewed motion for temporary restraining order filed by plaintiffs Planned Parenthood of Arkansas & Eastern Oklahoma, d/b/a Planned Parenthood of the Heartland (“PPAEO”) and Stephanie Ho, M.D., on behalf of themselves and their patients (Dkt. No. 84). Plaintiffs bring this action seeking declaratory and injunctive relief on behalf of themselves and their patients under the United States Constitution and 42 U.S.C. § 1983 to challenge Section 1504(d) of the Abortion-Inducing Drugs Safety Act, 2015 Arkansas Acts 577 (2015) (“Section 1504(d),” “the Act,” or “the contracted physician requirement”), codified at Arkansas Code Annotated § 20-16-1501 et seq. This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343(a)(3). Defendants Larry Jegley, prosecuting attorney for Pulaski County, in his official capacity, his agents and successors, and Matt Durrett, prosecuting attorney for Washington County, in his official capacity, his agents and successors, responded in opposition to the motion (Dkt. No. 101). -

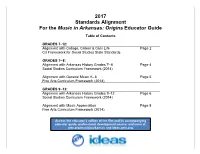

Standards Alignment

2017 Standards Alignment For the Music in Arkansas: Origins Educator Guide Table of Contents GRADES 7–12: Alignment with College, Career & Civic Life Page 2 C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards GRADES 7–8: Alignment with Arkansas History Grades 7–8 Page 4 Social Studies Curriculum Framework (2014) Alignment with General Music K–8 Page 5 Fine Arts Curriculum Framework (2014) GRADES 9–12: Alignment with Arkansas History Grades 9–12 Page 6 Social Studies Curriculum Framework (2014) Alignment with Music Appreciation Page 8 Fine Arts Curriculum Framework (2014) Access the educator’s edition of the film and its accompanying educator guide, professional development course, and more at: aetn.org/musicinarkansas and ideas.aetn.org. Alignment with College, Career & Civic Life C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards LOCATION STANDARD/COMPONENT IN GUIDE DIMENSION 1: DEVELOPING QUESTIONS & PLANNING INQUIRIES Alignment with Components of the Inquiry Arc: Compelling Questions: The questions associated with standards have been framed in the form of “compelling questions.” Students may also be encouraged to develop their own compelling questions, which would further support standards within Dimension One. Supporting Questions: The remainder of the questions for each era have been framed in the form of “supporting questions.” Helpful Sources: Our recommended resources can be found on P12 of the educator guide. Students may also be encouraged to find and evaluate resources on their own. Formative Tasks: The discussion and writing tasks for each era have been designed as “formative tasks.” DIMENSION 2: APPLYING DISCIPLINARY CONCEPTS & TOOLS Individual C3 Framework standards for civics, economics, geography, history, and anthropology are referenced throughout this document and are aligned with Arkansas standards.