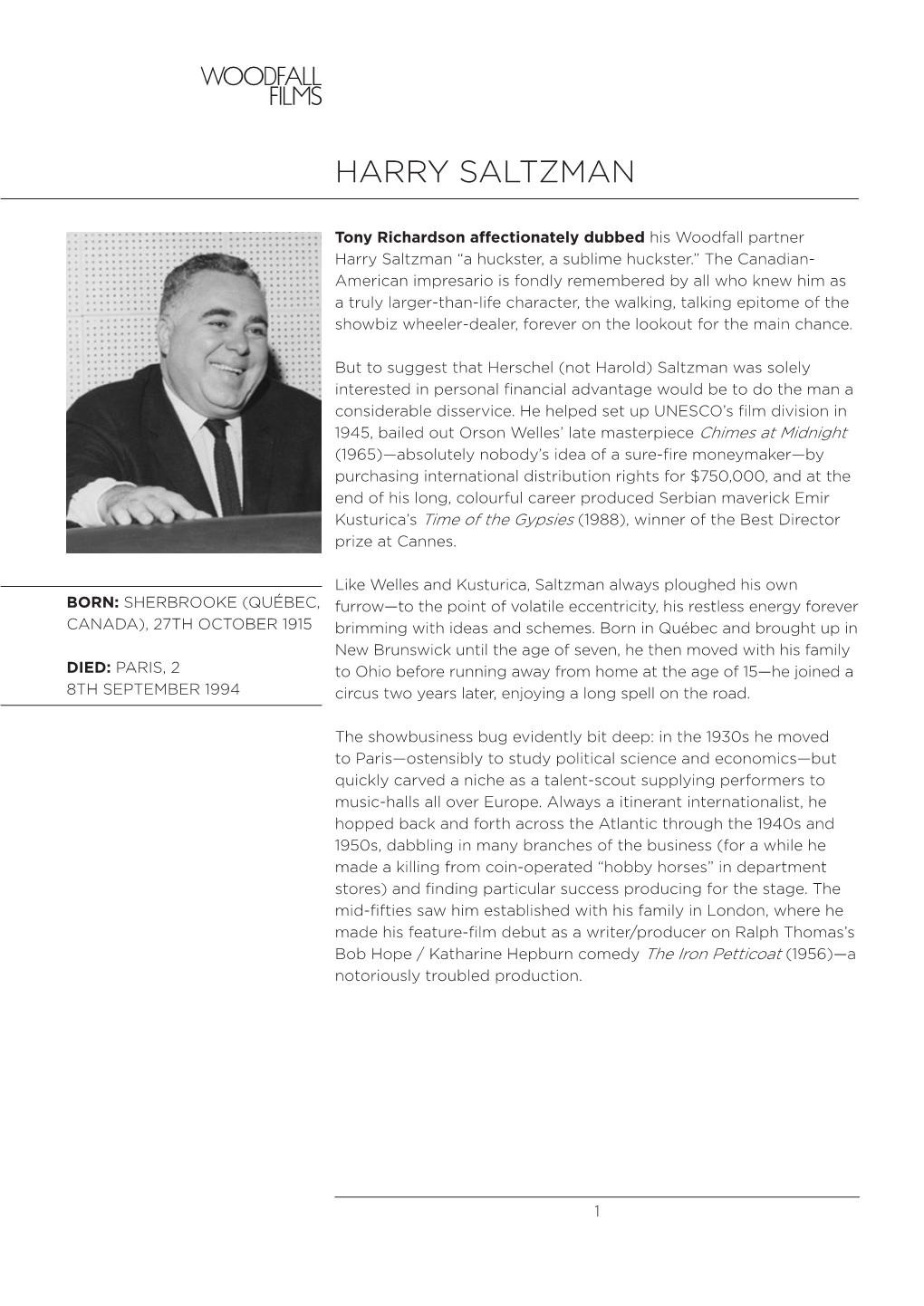

Harry Saltzman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

On Her Majesty's Secret Service"

SCHILTHORN CABLEWAY LTD – MEDIA RELEASE 50 Years "On Her Majesty's Secret Service" Interlaken, Mürren, 18 April 2019: Fifty years ago, filming wrapped on the iconic James Bond movie "On Her Majesty's Secret Service" and the film launched in cinemas worldwide. Schilthorn Cableway is looking back and planning a special anniversary weekend. "Schilthorn Cableway is focusing its strategy on the unsurpassed mountain landscape and the legend surrounding James Bond," says Schilthorn Cableway CEO Christoph Egger. Filming for the James Bond movie On Her Majesty's Secret Service ran from 21 October 1968 to 17 May 1969 in the village of Mürren and on the Schilthorn summit. "The Schilthorn wouldn't exist in its current form without the film," Egger continues. More than enough reason to celebrate the 50th anniversary in style. Anniversary weekend with public autograph signing In order to mark the anniversary with James Bond fans from all over the globe, a special anniversary weekend has been put together by Martjin Mulder of On the Tracks of 007. The tour takes in the film's various settings and locations and includes a gala evening on the Schilthorn summit. Schilthorn Cableway has an autograph signing planned for Sunday, 2 June 2019, taking place at the Hotel Eiger in Mürren from 10:30 am to 12:30 pm. Several actors and other personalities with connections to the film are expected to attend: Catherine Schell (Nancy), Eddie Stacey (Stuntman), Erich Glavitza (Coordinator, stock car race and drivers), George Lazenby (James Bond), Helena Ronee (Israeli Girl), Jenny Hanley (Irish Girl), John Glen (2nd Unit Director, Editor, Director of Five Bond Films), Monty Norman (Composer of the original Dr. -

Museum Salutes James Bond and His Creators Critic Judith Crist Moderates Forum

The Museum of Modern Art % 50th Anniversary to MUSEUM SALUTES JAMES BOND AND HIS CREATORS CRITIC JUDITH CRIST MODERATES FORUM In any time capsule of the 20th century, there is sure to be a commentary on and, more than likely, a print of a James Bond movie. So great is the impact of Secret Agent 007, archetypical hero of the second half of this century, that it is estimated one out of three people throughout the world have at one time or another viewed one of his spy thrillers. The most popular Bond film so far, "The Spy Who Loved Me" reportedly has drawn one and a half billion viewers or over one eighth of the earth's population. Given these facts, the Department of Film of The Museum of Modern Art, considers the phenomenon of James Bond noteworthy and is rendering, at an appropriate time concurrent with the premiere of the new James Bond "Moonraker," an homage to the producer, Albert R. Broccoli and his colleagues. Recognizing that each of the Bond films is a collabora tive project, Larry Kardish, Associate Curator in the Department of Film, has included in this tribute Lewis Gilbert, the director, Ken Adam, production designer, and Maurice B inder, title creator and graphics artist. The James Bond program, organized by Mr. Kardish, opens on June 25, with a documentary titled "The Making Of James Bond." It takes the viewer behind the scenes of the production of "The Spy Who Loved Me." Produced by BBC, it consists of four half-hour films: the first deals 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. -

37 Agenda Bibliomediateca Dal 26.10 Al 01.11.2012 Ok

Agenda settimanale degli eventi in Bibliomediateca da venerdì 26 ottobre a giovedì 1 novembre 2012 Bibliomediateca “Mario Gromo” - Sala Eventi Via Matilde Serao 8/A, Torino tel. +39 011 8138 599 - email: [email protected] Sommario: 29.10 – SHAKESPEARE A HOLLYWOOD – La sottana di ferro di Ralph Thomas (ore 15.30) 30.10 – NUOVI ORIZZONTI DELLA TEORIA E DELLA STORIOGRAFIA – Il cinema italiano negli anni ’30: nuove ricerche (15.00) LUNEDI’ 29 OTTOBRE – ORE 15.30 Ultimo appuntamento della rassegna SHAKESPEARE A HOLLYWOOD con la proiezione del film La sottana di ferro di Ralph Thomas. Ultimo appuntamento della rassegna SHAKESPEARE A HOLLYWOOD. Ben Hecht sceneggiatore con la proiezione, lunedì 29 ottobre , alle ore 15.30 , nella sala eventi della Bibliomediateca, del film La sottana di ferro di Ralph Thomas. Realizzato nel 1956 da Ralph Thomas, il film fu sceneggiato in origine da Ben Hecht che aveva scelto un titolo completamente differente: Not For Money. Svariate vicissitudini produttive e l’arrivo di Bob Hope nel ruolo del co-protagonista (inizialmente assegnato a Cary Grant) causarono non pochi problemi: Hope e i suoi scrittori modificarono intere parti di sceneggiatura tagliando le maggiori scene con la Hepburn e modificando il titolo in The Iron Petticoat. Questa operazione non piacque a Hecht che decise di abbandonare il progetto rifiutandosi persino di apparire nei credits. La commedia, fortemente influenzata da Ninotchka - film del 1939 di Ernst Lubitsch - nonostante l'abbandono di Hecht, conserva, in alcune parti, il “tocco” dello sceneggiatore americano nei classici dialoghi/battibecchi tra i due protagonisti e nell'ironia con cui si prende gioco dei tipici cliché anticomunisti dell'epoca. -

Goldfinger: James Bond 007 Ebook Free Download

GOLDFINGER: JAMES BOND 007 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ian Fleming,Kate Mosse | 384 pages | 04 Oct 2012 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099576075 | English | London, United Kingdom Goldfinger: James Bond 007 PDF Book Previously, he wrote for Taste of Cinema and BabbleTop. Goldfinger audio commentary. Goldfinger's own gold will then increase in value and the Chinese gain an advantage from the resulting economic chaos. Retrieved 18 July Films produced by Harry Saltzman. Retrieved 1 June Retrieved 1 October Goldfinger plans to breach the U. Do you like this video? You can read all about him in this archived NY Times obituary. Company Credits. The road is now called Goldfinger Avenue. Views Read Edit View history. Edit Cast Cast overview, first billed only: Sean Connery The film's plot has Bond investigating gold smuggling by gold magnate Auric Goldfinger and eventually uncovering Goldfinger's plans to contaminate the United States Bullion Depository at Fort Knox. Share Share Tweet Email 0. No , suggested the scene where Oddjob puts his car into a car crusher to dispose of Mr. Jill Masterson. In the vault, Goldfinger's henchman, Kisch, handcuffs Bond to the bomb. In the film, Bond notes it would take twelve days for Goldfinger to steal the gold, before the villain reveals he actually intends to irradiate it with the then topical concept of a Red Chinese atomic bomb. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Fiddling with Goldfinger's golf set, Bond discovers a hidden room with a safe containing details of a meeting for "Operation Bluegrass". Start a Wiki. Plot Keywords. Namespaces Article Talk. Goldfinger: James Bond 007 Writer London: Bloomsbury Publishing. -

Bond File the Bonds Were New and Which Creates an Immediate Bond First Exercised His License to Kill in Fleming's Dynamic

CULTURE 'The target of my books lies occasioned by working on somewhere between the Bend Below something that is not unequi- solar plexus and the upper vocably 'right on'. After all, thigh', said Ian Fleming of The Belt these are films which the his James Bond novels, Left regards as sexist and neatly summing up their at- James Bond returns this month with Licence To Kill. Sally racist and stemming directly traction and intention as well Hibbin, a confirmed Bond girl, explains the fascination of from, and maybe even fuel- as that of the films. Fle- the long-running series of films ling, the cold-war climate. ming's novels were imme- But to write them off in that diately popular in England way is too easy because I, when they came out in the like I suspect many other 50s but only made it interna- readers of Marxism Today, tionally when John F Ken- thoroughly enjoy the Bond nedy included them in a list films. They are exciting to of his favourite, presidential watch and eminently satisfy- bedside reading. The films, ing. beginning with Dr No in There are, of course, those 1962, have become the most who will quarrel with even successful movie series of that. The Bond films, they all time. argue, are too predictable, It is estimated that over too similar to each other to half the world's population be interesting. If you've seen has seen a Bond film at one one you've seen them all. But time or another, and this wi- these critics are missing the thout the films ever having fun of the series. -

Montana Kaimin, November 21, 1980 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 11-21-1980 Montana Kaimin, November 21, 1980 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, November 21, 1980" (1980). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 7083. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/7083 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. montana kaimin Friday, Nov. 21,1980 Missoula, Mont. Vol. 83, No. 27 Hunger myths challenged By MICHAEL CRATER • the myth that technology can they inevitably underuse and mis Montana Kalmln Reporter solve hunger problems. Collins use the producing resources,” he said that improvements in said. An example he cited was one World hunger is not caused by technology favor only those who district in India where he said scarcity and cannot be resolved by control the productive land. They increased technology and increased technology, cannot be tend to use technology to produce American aid has led to solved or even decreased by foods for export, and to do so with agricultural “yields three times American aid and cannot be blam less labor, he said. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Film Criticism

ALEXANDER FEDOROV FILM CRITICISM FEDOROV, A. FILM CRITICISM. МOSCOW: ICO “INFORMATION FOR ALL”. 2015. 382 P. COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY ALEXANDER FEDOROV [email protected] ALL RIGHT RESERVED. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 2 1 FEDOROV, ALEXANDER. 1954-. FILM CRITICISM / ALEXANDER FEDOROV. P. CM. INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES. 1. FILM CRITICISM. 2. FILM STUDIES. 3. MEDIA LITERACY. 4. MEDIA EDUCATION. 5. MEDIA STUDIES. 6. FILM EDUCATION. 7. STUDENTS. 8. CINEMA. 9. FILM. 10. MASS MEDIA. 11. STUDY AND TEACHING. 2 Contents The Mystery of Russian Cinema ………………………………..…... ..6 Phenomenon of Russian Film-Hits ………………………………….. 10 Russian Screen Distribution …………………………………..………..12 Video-pirates from Russia ……………………………………..…….. 15 Film Criticism and Press in Russia …………………………………… 17 Russian Cinematography and the Screen Violence ………………....….21 The Gloom of Russian Fantastic Movie-Land …………….………..….27 Sex-Cinema: Made in Russia …………………………………… ..….. 29 America, America… ……………………………………………….… .31 French Motives and Russian Melodies ………………………….…… .33 Fistful of Russian Movies ……………………………………….…… .41 Nikita Mikhalkov before XXI Century ………………………….…… 78 Karen Shakhnazarov: a Fortune's Favorite? ……………………….… 86 Pyotr Todorovsky: Dramatic Romance ……………………….……. 92 Oleg Kovalov, Former Film Critic .........................................................99 How to Shoot the “True” Film about Russia …………………………102 Locarno Film Fest: The View of a Film Educator ……………………103 The Analysis of Detective Genre at Film Education in Students’ Audience ……………………………………………… ……….…..106 Hermeneutical -

The Depiction of Scientists in the Bond Film Franchise Claire Hines

The depiction of scientists in the Bond film franchise Claire Hines The James Bond film franchise began with the release of Dr No (Terence Young, 1962), a film of many notable firsts for the long-running and highly formulaic series. These important firsts include the introduction of Sean Connery as James Bond, the introduction of the criminal organisation SPECTRE and the first major Bond villain, the first of the Bond girls, and a number of key recurring characters. Even though some changes were made to the novel written by Ian Fleming (and published in 1958), the film nevertheless follows the same storyline, where Bond is sent by the British Secret Service to Jamaica and uncovers an evil plot headed by a scientific mastermind. As the first of the Bond films, it is particularly significant that Dr No has a scientist as the very first on-screen Bond villain. Played by Joseph Wiseman, Dr No was based on the literary character from Fleming’s novel, and clearly followed in the tradition of the mad scientist, but also became the prototype for the many Bond villains that followed in the film series (Chapman 2007: 66). According to the stories that circulate about the preparation of Dr No, however, this was almost not the case. In his autobiography Bond producer Albert Broccoli recalls that he and Harry Saltzman rejected an early draft of the screenplay in which the screenwriters had departed from the novel and made the villain a monkey (1998: 158). Broccoli was adamant that the script needed to be rewritten and that Fleming’s Bond villain should be restored to the screenplay (1998: 158). -

Goldfinger (Analyse) Réal La Rochelle

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 00:22 Séquences La revue de cinéma Goldfinger (analyse) Réal La Rochelle Le cinéma imaginaire II Numéro 55, décembre 1968 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/51628ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (imprimé) 1923-5100 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article La Rochelle, R. (1968). Goldfinger (analyse). Séquences, (55), 31–35. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1968 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ GOLDFINGER DÉCEMBRE 1968 31 ^r. aLJOcumentatio 1. Générique minant un style de fabrication auquel Guy Hamilton a dû se plier. Anglais 1964 — Technicolor — Prod. : Harry Saltzman et Albert R. Broccoli — 3. Le scénario Real. : Guy Hamilton —• Seen. : Richard Maibaum et Paul Dehn, d'après lan Fle Après le sigle de la production, un ming — Phot. : Ted Moore — Mus. : pré-générique montre James Bond fai John Barry — Decors : Ken Adams •— sant sauter un complexe industriel, Effets spéciaux : John Steers — Généri puis, parfait gentleman, il électrocute que : Robert Brownjohn — Mont. : Peter un tueur dans la chambre d'une fille : Hunt •—• Int.: Sean Connery (James "shocking" ! murmure-t-il. -

Arrow Video Arrow Vi Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Vi

VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO ARROW 1 VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO PSYCHOMANIA ARROW 2 VIDEO ARROW CAST George Sanders … Shadwell Beryl Reid … Mrs Latham Robert Hardy … Chief Inspector Hesseltine Nicky Henson … Tom Mary Larkin … Abby Roy Holder … Bertram ARROW Director of PhotographyCREW Ted Moore B.S.C. Screenplay by Arnaud D’Usseau and Julian Halevy Film Editor Richard Best Stunt SupervisorArt Director Gerry Maurice Crampton Carter Music by John Cameron Produced by Andrew Donally Directed by Don Sharp 3 VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CONTENTS 4 ARROW 6 Cast and Crew VIDEO An Outstanding Appointment with Fear (2016) 12ARROW by Vic Pratt The Last Movie: George Sanders and Psychomania (2016) VIDEO 18 by William Fowler Psychomania – Riding Free (2016) ARROW 26 by Andrew Roberts VIDEO Taste for Excitement: An Interview with Don Sharp (1998) 38 by Christopher Koetting ARROW VIDEOAbout the Restoration ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO ARROW 4 VIDEO ARROW ARROW 5 VIDEO VIDEO ARROW The thing is, kids, back before cable TV, Netflix or the interweb, old horror films were only AN OUTSTANDING APPOINTMENT WITH FEAR shown on British telly late at night, in a slot clearly labelled ‘Appointment with Fear’, or, for VIDEO the absolute avoidance of doubt, ‘The Horror Film’.