A Case for Change in Indian Historic Preservation Planning: Re-Evaluating Attitudes Toward the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UP State Biodiversity Board BBIIOODDIIVV Nneewwss Volume : 6 N Issue : 22 N Jan - Mar 2015 a Quarterly E‐Newsletter

UP State Biodiversity Board BBIIOODDIIVV NNeewwss Volume : 6 n Issue : 22 n Jan - Mar 2015 A Quarterly e‐Newsletter Editorial Esteemed Readers, Environmentalists, biologists and others concerned about the health of the planet and its inhabitants recognize the key role wetlands play in life on Earth. Besides containing a disproportionately high number of plant and animal species compared to other land forms, wetlands serve a variety of ecological services including feeding downstream waters, trapping floodwaters, recharging groundwater supplies, removing pollution and providing fish and wildlife habitat. Wetlands are critical for human development and wellbeing, especially in India where a large number of people are dependent on them for drinking water, food and livelihood. Despite their immense importance, wetlands are one of the most degraded ecosystems globally. Research suggests that over-exploitation of fish resources, discharge of industrial effluents, fertilizers and pesticides and uncontrolled siltation Painted storks and weed infestation, among other reasons, have wiped out or severely damaged over Photo Credit : (Mycteria leucocephala) Neeraj Mishra 1/3rd of India's wetlands. Wetlands are on the “front-line” as development pressures increase everywhere. When they are viewed as unproductive or marginal lands, wetlands are targeted for drainage and conversion. The rate of loss and deterioration of wetlands is accelerating in all regions of the world. The pressure on wetlands is likely to intensify in the coming decades due to increased global demand for land and water, as well as climate change. The Wetlands (Conservation and Management) Rules, 2010 is a positive step towards conservation of wetlands in India. Under the Rules, wetlands have been classified for better management and easier identification. -

Factors Responsible for Adoption of Gobindabhog Rice in Some Selected Areas of Burdwan District, West Bengal, India

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2019) 8(2): 107-113 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 8 Number 02 (2019) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2019.802.013 Factors Responsible for Adoption of Gobindabhog Rice in Some Selected Areas of Burdwan District, West Bengal, India Chowdhury Nazmul Haque*, Dinesh Das Kaibartya and Arup Kumar Bandyopadhyay Department of Agricultural Extension, Bidhan Chandra KrishiViswavidyalaya, Mohanpur, Nadia, West Bengal, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Adoption is a process of making a decision about an innovation of technology option offered to anyone. Even though we have brought about green revolution and moving for second green revolution, more than 60% of technology cannot reach the domain of farmer‟s innovation decision. So the present study takes care of adoption process of „Gobindabhog‟ famous traditional aromatic rice, to explore the process and complexity of Ke yw or ds its adoption and subsequent socialization. Aromatic rice like Gobindabhog has got social, ecological and economic importance. The general objective is estimating the factors Adoption, Aromatic responsible for adoption of Gobindabhog rice and following are the specific objectives: -1. rice, Gobindabhog To find out the relationship of the selected independent variables with the adoption behaviour of the farmers engaged in „Gobindabhog‟ rice cultivation. 2. To identify the Article Info degree to which the adoption behaviour may be predicted from this characteristics. 3. To access the different problems faced by the farmers hindering the adoption process and the Accepted: measures suggested by them as remedies. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Ministry of Culture Government of India

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 MINISTRY OF CULTURE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 1 Ministry of Culture 2 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview – 5 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India – 11 2.2 Museums – 28 2.2a National Museum – 28 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art – 31 2.2c Indian Museum – 37 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall – 39 2.2e Salar Jung Museum – 41 2.2f Allahabad Museum – 44 2.2g National Council of Science Museum – 46 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities – 50 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology – 50 2.3.b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property – 51 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) – 54 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) – 57 2.6 UNESCO Matters – 59 2.7 National Missions – 61 2.7a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities – 61 2.7b National Mission for Manuscripts – 61 2.7c National Mission on Libraries – 64 2.7d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites – 65 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama – 69 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts – 72 3.3 Akademies – 75 3.3a Sahitya Akademi – 75 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi – 77 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi – 81 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training – 85 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation – 90 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres – 94 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre – 95 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre – 95 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre – 96 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre – 97 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre – 99 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site 3 Ministry of Culture 4. -

MGNREGA): Its Impact and Women’S Participation Dr

International Journal of Research in management ISSN 2249-5908 Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ijrm/ijrm_index.htm Issue 2, Vol. 6 (November-2012) Examining India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA): Its Impact and Women’s Participation Dr. Dinesh Das Assistant Professor, Dept. of Economics, Gossaigaon College, Kokrajhar, Assam, INDIA __________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is the central government response to the constitutionally manifested right to work and means to promote livelihood security in India’s rural areas. MGNREGA is the flagship rural employment generation programme in rural areas for 100 days in a financial year. While providing employment, priority shall be given to women in such a way that at least one-third of the beneficiaries shall be women who have registered and requested for work under the scheme. Equal wages shall be paid to both men and women workers. By generating employment for women at fair wages in the village, NREGA can play a substantial role in economically empowering women and laying the basis for greater independence and self- esteem. One of the most distinguishing features of MGNREGA is its approach towards empowering citizen including women citizen to play an active role in the implementation of the scheme, through gram sabha, social audit, participatory planning and other activities. Keywords: MGNREGA, Women’s Participation, Development, NE India __________________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Gender is the inevitable push factor for growth and development of a nation like India. In India women constitute a major share of chronically poor population. They are facing vulnerabilities of life. -

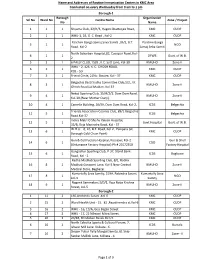

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

ANSWERED ON:23.08.2007 HISTORICAL PLACES in up Verma Shri Bhanu Pratap Singh

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1586 ANSWERED ON:23.08.2007 HISTORICAL PLACES IN UP Verma Shri Bhanu Pratap Singh Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) the details of Centrally protected monuments in Uttar Pradesh (UP) at present; (b) the agency responsible for the maintenance of these places; (c) the amount spent on the maintenance of these monuments during the last three years; and (d) the details of revenue earned from these monuments during each of the last three years? Answer MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND CULTURE (SHRIMATI AMBIKA SONI) (a)&(b) There are 742 monuments/sites declared as of national importance in the Uttar Pradesh (U.P.) as per list at Annexure. Archaeological Survey of India looks after their proper upkeep, maintenance, conservation and preservation. (c) The expenditure incurred on conservation, preservation, maintenance and environmental development of these centrally protected monuments during the last three years is as under: Rupees in Lakhs Year Total 2004-05 1392.48 2005-06 331.14 2006-07 1300.36 (d) The details of revenue earned from these monuments during the last three years are as under: Rupees in Lakhs Year Total 2004-05 2526.33 2005-06 2619.92 2006-07 2956.46 ANNEXURE ANNEXURE REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PART (a)&(b) OF THE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTIO NO.1586 FOR 23.8.2007 LIST OF CENTRALLY PROTECTED MONUMENTS IN UTTAR PRADESH Agra Circle Name of monument/site Locality District 1. Agra Fort Including Akbari Mahal Agra Agra Anguri Bagh Baoli of the Diwan-i-Am Quadrangle. -

Sync Sound and Indian Cinema | Upperstall.Com 29/02/12 2:30 PM

Sync Sound and Indian Cinema | Upperstall.Com 29/02/12 2:30 PM Open Feedback Dialog About : Wallpapers Newsletter Sign Up 8226 films, 13750 profiles, and counting FOLLOW US ON RECENT Sync Sound and Indian Cinema Tere Naal Love Ho Gaya The lead pair of the film, in their real life, went in the The recent success of the film Lagaan has brought the question of Sync Sound to the fore. Sync Sound or Synchronous opposite direction as Sound, as the name suggests, is a highly precise and skilled recording technique in which the artist's original dialogues compared to the pair of the are used and eliminates the tedious process of 'dubbing' over these dialogues at the Post-Production Stage. The very first film this f... Indian talkie Alam Ara (1931) saw the very first use of Sync Feature Jodi Breakers Sound film in India. Since then Indian films were regularly shot I'd be willing to bet Sajid Khan's modest personality and in Sync Sound till the 60's with the silent Mitchell Camera, until cinematic sense on the fact the arrival of the Arri 2C, a noisy but more practical camera that the makers of this 'new particularly for outdoor shoots. The 1960s were the age of age B... Colour, Kashmir, Bouffants, Shammi Kapoor and Sadhana Ekk Deewana Tha and most films were shot outdoors against the scenic beauty As I write this, I learn that there are TWO versions of this of Kashmir and other Hill Stations. It made sense to shoot with film releasing on Friday. -

West Bengal Towards Change

West Bengal Towards Change Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation Research Foundation Published By Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation 9, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 Web :- www.spmrf.org, E-Mail: [email protected], Phone:011-23005850 Index 1. West Bengal: Towards Change 5 2. Implications of change in West Bengal 10 politics 3. BJP’s Strategy 12 4. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 14 Statements on West Bengal – excerpts 5. Statements of BJP National President 15 Amit Shah on West Bengal - excerpts 6. Corrupt Mamata Government 17 7. Anti-people Mamata government 28 8. Dictatorship of the Trinamool Congress 36 & Muzzling Dissent 9. Political Violence and Murder in West 40 Bengal 10. Trinamool Congress’s Undignified 49 Politics 11. Politics of Appeasement 52 12. Mamata Banerjee’s attack on India’s 59 federal structure 13. Benefits to West Bengal from Central 63 Government Schemes 14. West Bengal on the path of change 67 15. Select References 70 West Bengal: Towards Change West Bengal: Towards Change t is ironic that Bengal which was once one of the leading provinces of the country, radiating energy through its spiritual and cultural consciousness across India, is suffering today, caught in the grip Iof a vicious cycle of the politics of violence, appeasement and bad governance. Under Mamata Banerjee’s regime, unrest and distrust defines and dominates the atmosphere in the state. There is a no sphere, be it political, social or religious which is today free from violence and instability. It is well known that from this very land of Bengal, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore had given the message of peace and unity to the whole world by establishing Visva Bharati at Santiniketan. -

Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh RPS ITC UPZJ7C Name Ram Piyare Singh Industrial Training Centre Address Maharwa Gola , , , Ambedkar Nagar - File Nos. DGET-6/24/16/2003-TC Govt. ITI UPZJ8C Name Govt. Industrial Training Institute, Tanda Address Tanda , , , Ambedkar Nagar - File Nos. DGET-6/24/7/2001-TC Chandra Audyogik UPZLPX Name Chandra Audyogik Prashikshan Kendra Address Dhaurhara, Sinjhauli , , , Ambedkar Nagar - File Nos. DGET-6/24/152/2009-TC WITS ITC UPZLQ4 Name WITS ITC Address Patel Nagar Akbarpur , , , Ambedkar Nagar - 224122 File Nos. DGET-6/24/160/2009-TC Kamla Devi Memorial Voc. UPZLT9 Name Kamla Devi Memorial Vocational Training Institute Address Pura Baksaray, Barua Jalaki, Tanda , , , Ambedkar Nagar - File Nos. DGET-6/24/235/2009-TC Hazi Abdullah ITC UPZLTK Name Hazi Abdullah ITC Address Sultanpur Kabirpur, Baskhari , , , Ambedkar Nagar - File Nos. DGET-6/24/238/2009-TC K.B.R ITC UPZM02 Name K.B.R ITC Address Shastri Nagar, Akbarpur , , , Ambedkar Nagar - File Nos. DGET-6/24/236/2009-TC Govt.ITI (W) Agra UP1750 Name Govt. Industrial Training Institute (Women Branch) Address , , , Agra - 0 File Nos. 0 Women Govt ITI, Agra UP1751 Name Govt. Industrial Training Institute for Women (WB) Address Vishwa Bank , , , Agra - 0 File Nos. DGET-6/24/16/2000-TC Govt ITI Agra UP1754 Name Govt Industrial Training Institute Address , , , Agra - 282001 File Nos. DGET-6/24/20/92 - TC Fine Arts Photography Tra UP2394 Name Fine Arts Photography Training Institute Address Baba Bldg. Ashok Nagar , , , Agra - 282001 File Nos. DGET-6/21/1/88 - TC National Instt of Tech Ed UPZJZ2 Name National Institute of Tech Educational Vijay Nagar Colony Address North Vijay Nagar Colony , , , Agra - 282004 File Nos. -

Indian Anthropology

INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN INDIA Dr. Abhik Ghosh Senior Lecturer, Department of Anthropology Panjab University, Chandigarh CONTENTS Introduction: The Growth of Indian Anthropology Arthur Llewellyn Basham Christoph Von-Fuhrer Haimendorf Verrier Elwin Rai Bahadur Sarat Chandra Roy Biraja Shankar Guha Dewan Bahadur L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer Govind Sadashiv Ghurye Nirmal Kumar Bose Dhirendra Nath Majumdar Iravati Karve Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia Dharani P. Sen Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas Shyama Charan Dube Surajit Chandra Sinha Prabodh Kumar Bhowmick K. S. Mathur Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi Triloki Nath Madan Shiv Raj Kumar Chopra Andre Beteille Gopala Sarana Conclusions Suggested Readings SIGNIFICANT KEYWORDS: Ethnology, History of Indian Anthropology, Anthropological History, Colonial Beginnings INTRODUCTION: THE GROWTH OF INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY Manu’s Dharmashastra (2nd-3rd century BC) comprehensively studied Indian society of that period, based more on the morals and norms of social and economic life. Kautilya’s Arthashastra (324-296 BC) was a treatise on politics, statecraft and economics but also described the functioning of Indian society in detail. Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya from 324 BC to 300 BC. He also wrote a book on the structure and customs of Indian society. Al Biruni’s accounts of India are famous. He was a 1 Persian scholar who visited India and wrote a book about it in 1030 AD. Al Biruni wrote of Indian social and cultural life, with sections on religion, sciences, customs and manners of the Hindus. In the 17th century Bernier came from France to India and wrote a book on the life and times of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, their life and times. -

Download Book

"We do not to aspire be historians, we simply profess to our readers lay before some curious reminiscences illustrating the manners and customs of the people (both Britons and Indians) during the rule of the East India Company." @h£ iooi #ld Jap €f Being Curious Reminiscences During the Rule of the East India Company From 1600 to 1858 Compiled from newspapers and other publications By W. H. CAREY QUINS BOOK COMPANY 62A, Ahiritola Street, Calcutta-5 First Published : 1882 : 1964 New Quins abridged edition Copyright Reserved Edited by AmARENDRA NaTH MOOKERJI 113^tvS4 Price - Rs. 15.00 . 25=^. DISTRIBUTORS DAS GUPTA & CO. PRIVATE LTD. 54-3, College Street, Calcutta-12. Published by Sri A. K. Dey for Quins Book Co., 62A, Ahiritola at Express Street, Calcutta-5 and Printed by Sri J. N. Dey the Printers Private Ltd., 20-A, Gour Laha Street, Calcutta-6. /n Memory of The Departed Jawans PREFACE The contents of the following pages are the result of files of old researches of sexeral years, through newspapers and hundreds of volumes of scarce works on India. Some of the authorities we have acknowledged in the progress of to we have been indebted for in- the work ; others, which to such as formation we shall here enumerate ; apologizing : — we may have unintentionally omitted Selections from the Calcutta Gazettes ; Calcutta Review ; Travels Selec- Orlich's Jacquemont's ; Mackintosh's ; Long's other Calcutta ; tions ; Calcutta Gazettes and papers Kaye's Malleson's Civil Administration ; Wheeler's Early Records ; Recreations; East India United Service Journal; Asiatic Lewis's Researches and Asiatic Journal ; Knight's Calcutta; India. -

Dtp1june29final.Qxd (Page 1)

DLD‹‰‰†‰KDLD‹‰‰†‰DLD‹‰‰†‰MDLD‹‰‰†‰C A shock for Hollywood Britney admits to drug use Oops, Britney Spears has ken cocaine in the toilet of Kid Rock: Pam calling: Bebo admitted to having da- a Miami nightclub. Now, THE TIMES OF INDIA bbled in drugs, qualif- of course, the star her- Sunday, dates Durst goes global! ying that it was ‘‘a big self has chosen to co- June 29, 2003 mistake.’’ Not daring me clean. Page 7 Page 8 to actually use the A less shocking word ‘drugs’, Britn- revelation is that Brit- ey explains, ‘‘Let’s ney likes to drink — just say you reach a her favourite tipple stage in your life is ‘‘Malibu and pine- when you are curio- apple juice.’’ But us. And I was curio- she denies cheating us at one point. But on Justin Timberla- I’m way too focused ke and says she was to let anything stop ‘‘shocked’’ to see a Br- me.’’ So,was it a mis- itney-lookalike in his take? ‘‘Yes.’’ video Cry Me a River, Interestingly, not which tells the story too long back, Britney of a woman cheat- maintained that she ing on her boyfriend. OF INDIA would ‘‘sue’’ a US But then, strange things magazine which had happen when love’s lab- THANK GOD IT’S SUNDAY alleged that she had ta- our is lost. Photos: RONJOY GOGOI MANOJ KESHARWANI SOORAJ BARJATYA: THE BIG PICTURE My family was my world: My ng around, my mother decided earliest memories date back to SUNDAY SPECIAL that I needed to get married im- a home full of uncles, aunts and mediately.