Handbook of Poisonous and Injurious Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

JOURNAL of the AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY, INC. July 1966 AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY

~GAZ.NE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY, INC. July 1966 AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY 1600 BLA DENSBURG ROA D, N O RT H EAST / W ASHIN GTON, D. c. 20002 Fo r United H orticulture *** to accum ula te, inaease, and disseminate horticultural information Editorial Committee Directors T erms Expi?'i71 g 1966 FRANCIS DE V OS, Cha irman J. H AROLD CLARKE J O H N L. CREECH Washingtoll FREDERIC P. LEE FREDERIC P. LEE Maryland CARLTON P. LEES CO~ R A D B. LI NK Massachusetts R USSELL J. S EIBERT FREnERICK C . M EYER Pennsylvan ia D ONALD WATSON WILBUR H. YOUNGMAN H awaii T erms Ex pi?'ing 1967 MRS. ROBERT L. E MERY, JR. o [ficers Louisiana A. C. HILDRETH PRESIDENT Colorado D AVID L EACH J OH N H . '''' ALKER Pennsylvania A lexand?'ia, Vi?'ginia CHARLES C . MEYER New York F IR ST VICE· PRESIDENT MRS. STANLEY ROWE Ohio F RED C. CALLE Pill e M ountain, Geo?-gia T erms Expi?-ing 1968 F RANCIS DE V OS M aryland SECON D VI CE-PRESIDENT MRS. E LSA U. K NOLL TOM D . T HROCKMORTON California Des ili/oines, I owa V ICTOR RIES Ohio S TEWART D. " ' INN ACTI NG SECRETARY·TREASURER GRACE P. 'WILSON R OBE RT WINTZ Bladensburg, Maryland Illinois The A merican Horticultural Magazine is the official publication of the American Horticultural Society and is issued four times a year during the quarters commencing with January, April, July and October. It is devoted to the dissemination of knowledge in the science and art of growing ornamental plants, fruits, vegetables, and related subjects. -

Site Report: Hotel Indigo Site, Volume 2 Appendices (2017)

INOVA CENTER FOR PERSONALIZED HEALTH Archeological Evaluation and Mitigation of Hotel Indigo (220 South Union Street) Daniel Baicy, M.A., RPA, David Carroll M.A., RPA, Elizabeth Waters Johnson, M.A. and John P. Mullen, M.A., RPA Volume II Hotel Indigo (220 South Union Street) Alexandria, Virginia WSSI #22392.02 Archaeological Evaluation and Mitigation at Site 44AX0229 September 2017 Revised December 2020 Prepared for: Carr City Centers 1455 Pennsylvania Ave NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20004 Prepared by: Daniel Baicy, M.A., RPA, David Carroll M.A., RPA, Elizabeth Waters Johnson, M.A. and John P. Mullen, M.A., RPA With Contributions from: Susan Trevarthen Andrews, ID Bones Linda Scott Cummings and R. A. Varney, PaleoResearch Institute, Inc. Kathryn Puseman, Paleoscapes Archaeobotanical Services Team, (PAST) LLC Michael J. Worthington and Jane I. Seiter, Oxford Tree‐Ring Laboratory 5300 Wellington Branch Drive, Suite 100 Gainesville, Virginia 20155 Tel: 703-679-5600 Email: [email protected] www.wetlandstudies.com TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................... i LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. iii LIST OF PLATES .................................................................................................................... v APPENDIX I ............................................................................................................................ -

Four Master Teachers Who Fostered American Turn-Of-The-(20<Sup>TH

MYCOTAXON ISSN (print) 0093-4666 (online) 2154-8889 Mycotaxon, Ltd. ©2021 January–March 2021—Volume 136, pp. 1–58 https://doi.org/10.5248/136.1 Four master teachers who fostered American turn-of-the-(20TH)-century mycology and plant pathology Ronald H. Petersen Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37919-1100 Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract—The Morrill Act of 1862 afforded the US states the opportunity to found state colleges with agriculture as part of their mission—the so-called “land-grant colleges.” The Hatch Act of 1887 gave the same opportunity for agricultural experiment stations as functions of the land-grant colleges, and the “third Morrill Act” (the Smith-Lever Act) of 1914 added an extension dimension to the experiment stations. Overall, the end of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th was a time for growing appreciation for, and growth of institutional education in the natural sciences, especially botany and its specialties, mycology, and phytopathology. This paper outlines a particular genealogy of mycologists and plant pathologists representative of this era. Professor Albert Nelson Prentiss, first of Michigan State then of Cornell, Professor William Russel Dudley of Cornell and Stanford, Professor Mason Blanchard Thomas of Wabash College, and Professor Herbert Hice Whetzel of Cornell Plant Pathology were major players in the scenario. The supporting cast, the students selected, trained, and guided by these men, was legion, a few of whom are briefly traced here. Key words—“New Botany,” European influence, agrarian roots Chapter 1. Introduction When Dr. Lexemual R. -

Lecture 30 Origins of Horticultural Science

Lecture 30 1 Lecture 30 Origins of Horticultural Science The origin of horticultural science derives from a confl uence of 3 events: the formation of scientifi c societies in the 17th century, the creation of agricultural and horticultural societies in the 18th century, and the establishment of state-supported agricultural research in the 19th century. Two seminal horticultural societies were involved: The Horticultural Society of London (later the Royal Horticulture Society) founded in 1804 and the Society for Horticultural Science (later the American Society for Horticultural Science) founded in 1903. Three horticulturists can be considered as the Fathers of Horticultural Science: Thomas Andrew Knight, John Lindley, and Liberty Hyde Bailey. Philip Miller (1691–1771) Miller was Gardener to the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries at their Botanic Garden in Chelsea and is known as the most important garden writer of the 18th century. The Gardener’s and Florist’s Diction- ary or a Complete System of Horticulture (1724) was followed by a greatly improved edition entitled, The Gardener’s Dictionary containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit and Flower Garden (1731). This book was translated into Dutch, French, German and became a standard reference for a century in both England and America. In the 7th edition (1759), he adopted the Linnaean system of classifi cation. The edition enlarged by Thomas Martyn (1735–1825), Professor of Botany at Cambridge University, has been considered the largest gardening manual to have ever existed. Miller is credited with introducing about 200 American plants. The 16th edition of one of his books, The Gardeners Kalendar (1775)—reprinted in facsimile edition in 1971 by the National Council of State Garden Clubs—gives direc- tions for gardeners month by month and contains an introduction to the science of botany. -

Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education Volume 25, Issue 2

Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education Volume 25, Issue 2 doi: 10.5191/jiaee.2018.25202 U.S. International Agricultural Development: What Events, Forces, Actors, and Philosophical Perspectives Presaged Its Approach? Brandon M. Raczkoski Center for Veterinary Health Sciences Oklahoma State University M. Craig Edwards Oklahoma State University Abstract The philosophical perspectives, including significant actors, events, and forces, that influenced and presaged the United States’ approach to international agricultural development are somewhat unclear. The purpose of this historical narrative, therefore, was to understand the key drivers responsible for forging the U.S. framework for technical agricultural assistance abroad, especially in its formative years. The study’s findings were reported by answering two questions. The first question explored historical events, including federal legislative acts and statutes, which precipitated the U.S. approach to international agricultural development. The second research question addressed the philosophical primers imbued in the U.S. approach to international agricultural development, including significant actors responsible for championing it. We assert the environmental pragmatism of Liberty Hyde Bailey and its other proponents was the philosophical foundation and worldview that informed many of the pioneers who guided the U.S. approach to offering agricultural assistance as part of the nation’s international development efforts. As such, we recommend the inclusion of certain aspects of environmentalism in agricultural and extension educator preparation with implications for international and domestic development, including long-term sustainability initiatives. Keywords: environmentalism; Extension; international agricultural development (IAD); sustainable agriculture; United States Agency for International Development (USAID) 11 Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education Volume 25, Issue 2 Introduction the significant factors influencing the U.S. -

Origins of Biocentric Thought and How Changes In

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses) Department of History 4-20-2007 "When Nature Holds the Mastery": The Development of Biocentric Thought in Industrial America Aviva R. Horrow University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Kathy Peiss This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "When Nature Holds the Mastery": The Development of Biocentric Thought in Industrial America Abstract This thesis explores the concept of "biocentrism" within the context of American environmental thought at the turn of the twentieth century. Biocentrism is the view that all life and elements of the universe are equally valuable and that humanity is not the center of existence. It encourages people to view themselves as part of the greater ecosystem rather than as conquerors of nature. The development of this alternative world view in America begins in mid-nineteenth to early twentieth century, during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization as some Americans began to notice the destruction they wrought on the environment and their growing disconnect with nature. Several individuals during this time introduced the revolutionary idea of biocentrism including: John Muir, Liberty Hyde Bailey, Nathaniel Southgate Shaler and Edward Payson Evans. This thesis traces the development of their biocentrism philosophies, attributing it to several factors: more mainstream reactions to the changes including the Conservation movement and Preservation movements, new spiritual and religious approaches towards nature, and Darwin's theory of evolution which spurred the development of the field of ecology and the concept of evolving ethics. -

West Michigan Pike Route but Is Most Visible Between Whitehall and Shelby

Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 198 Oceana Drive, Rothbury New England Barn & Queen Anne Residence Hart-Montague Trail, Rothbury The trail is twenty-two miles of the former rail bed of the Pere Marquette Railroad. It was made a state park in 1988. The railroad parallels much of the West Michigan Pike route but is most visible between Whitehall and Shelby. New Era New Era was found in 1878 by a group of Dutch that had been living in Montague serving as mill hands. They wanted to return to an agrarian lifestyle and purchased farms and planted peach orchards. In 1947, there were eighty-five Dutch families in New Era. 4856 Oceana, New Era New Era Canning Company The New Era Canning Company was established in 1910 by Edward P. Ray, a Norwegian immigrant who purchased a fruit farm in New Era. Ray grew raspberries, a delicate fruit that is difficult to transport in hot weather. Today, the plant is still owned by the Ray family and processes green beans, apples, and asparagus. Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 199 4775 First Street, New Era New Era Reformed Church 4736 First Street, New Era Veltman Hardware Store Concrete Block Buildings. New Era is characterized by a number of vernacular concrete block buildings. Prior to 1900, concrete was not a common building material for residential or commercial structures. Experimentation, testing and the development of standards for cement and additives in the late 19th century, led to the use of concrete a strong reliable building material after the turn of the century. Concrete was also considered to be fireproof, an important consideration as many communities suffered devastating fires that burned blocks of their wooden buildings Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 200 in the late nineteenth century. -

Tote Gal/Eae. EAST LANSING . . . Julu 1945 • **••••••• Albert John Cepela, 1946 Albert J

JUL 23 1945 LIBRARY MiCHMJAN VTATtf CUt.LRGB QFAOKI. AINU AFP SCIMNC* y *k»L }*• .- •'••- WLM~- 1 *Z±£"M W* h *£ w l:m&r'^jfc&*<* tote Gal/eae. EAST LANSING . Julu 1945 • **••••••• Albert John Cepela, 1946 Albert J. Cepela, a private first class in the Army, was killed in action in France on March 7, 1945. Pfc. Cepela entered from Grand Rapids * ^llt&ie Men Qaue AU * and was enrolled in engineering during 1942-43. Chester F. Czajkowski, 1944 *****•••** Lt. Chester F. Czajkowski, a B-24 pilot and holder of the Air Medal and the Purple Heart, was killed in action in the Pacific area on March 10, 1945. Lt. Czajkowski entered from Ham- Leland Keith Dewey, 192S John H. Spalink, Jr., 1944 tramck and was enrolled as a sophomore in engi Leland K. Dewey, a major in the Army, died in John H. Spalink, Jr.. a staff sergeant in in neering during 1941-42. a Japanese prison camp in the Philippine Islands fantry, was killed in action on Luzon Island in on July 24, 1942. Major Dewey was graduated in the Philippines on February 4, 1945. Entering Jack Chester Grant, 1945 engineering on June 22. 1925, entering from from Grand Rapids. Michigan, Sgt. Spalink was Cedar Springs, Michigan. He is survived by his enrolled in business administration during 1940-42. Jack C. Grant, a second lieutenant in the Army, wife, the former Dorothy Fisk. w'27, a son. a was killed in action in Germany on March 16, daughter, and his parents. 1945. Lt. Grant was enrolled in business admin James David Evans, 1941 istration during 1941-43, entering from Grand James D. -

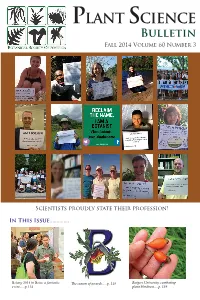

PLANT SCIENCE Bulletin Fall 2014 Volume 60 Number 3

PLANT SCIENCE Bulletin Fall 2014 Volume 60 Number 3 Scientists proudly state their profession! In This Issue.............. Botany 2014 in Boise: a fantastic The season of awards......p. 119 Rutgers University. combating event......p.114 plant blindness.....p. 159 From the Editor Reclaim the name: #Iamabotanist is the latest PLANT SCIENCE sensation on the internet! Well, perhaps this is a bit of BULLETIN an overstatement, but for those of us in the discipline, Editorial Committee it is a real ego boost and a bit of ground truthing. We do identify with our specialties and subdisciplines, Volume 60 but the overarching truth that we have in common Christopher Martine is that we are botanists! It is especially timely that (2014) in this issue we publish two articles directly relevant Department of Biology to reclaiming the name. “Reclaim” suggests that Bucknell University there was something very special in the past that Lewisburg, PA 17837 perhaps has lost its luster and value. A century ago [email protected] botany was a premier scientific discipline in the life sciences. It was taught in all the high schools and most colleges and universities. Leaders of the BSA Carolyn M. Wetzel were national leaders in science and many of them (2015) had their botanical roots in Cornell University, as Biology Department well documented by Ed Cobb in his article “Cornell Division of Health and University Celebrates its Botanical Roots.” While Natural Sciences Cornell is exemplary, many institutions throughout Holyoke Community College the country, and especially in the Midwest, were 303 Homestead Ave leading botany to a position of distinction in the Holyoke, MA 01040 development of U.S. -

Taxonomy and Arboretum Design

Taxonomy and Arboretum Design Scot Medbury In the second half of the nineteenth century, arboreta joined natural history museums and zoological gardens as archetypal embodiments of the Victorian fascination with the natural world. Grouping plants by type is a familiar practice tions. This is especially problematic when the in North American gardens where small, sepa- concept is applied to a plant collection that rate collections of maples, oaks, or other gen- strives to be all-inclusive. The arboretum era are common features. Although it is now projects of the Olmsted landscape architec- unusual to follow a taxonomic scheme in the tural firms illustrate some of these problems layout of an entire garden, such arrangements and also exhibit how changes in plant tax- were the vogue in nineteenth-century botani- onomy were expressed in the landscape. cal gardens and arboreta. The plant collections Historical in these gardens were frequently grouped into Background families or genera and then planted out along The historical antecedents for arranging plant a winding pathway so that visitors encoun- collections taxonomically include the first Eu- tered specimens in a taxonomic sequence. ropean botanical garden, the Orto Botanica, Growing related plants together, in effect, founded in Pisa in 1543. The plants in this gar- organizes a collection into a living encyclope- den were grouped according to their medicinal dia, allowing for comparison of the character- properties and, by the end of the sixteenth cen- istics of species within a genus or genera tury, by morphological characteristics as well within a family. By planting related taxa in an (Hill 1915). -

The Proposal for the Liberty Hyde Bailey Walk At

THE PROPOSAL FOR THE LIBERTY HYDE BAILEY WALK FOR THE AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY IN ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA by Melody Joy Gray A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Public Horticulture Spring 2006 Copyright 2006 Melody Joy Gray All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 1435928 UMI Microform 1435928 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 THE PROPOSAL FOR THE LIBERTY HYDE BAILEY WALK FOR THE AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY IN ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA by Melody Joy Gray Approved: __________________________________________________________ Robert E. Lyons, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Robin W. Morgan, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: __________________________________________________________ Conrado M. Gempesaw, II, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Academic and International Programs ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this thesis is the culmination of months of hard work and dedication. Special thanks are extended to my thesis committee: Bob Lyons, Ron Kagawa, Jim Swasey, and Tom Underwood. Thank you for your hours of editing and advising and your thoughtful insights. I truly had no clue how to accomplish this when I started and now look where I am because of you! Gerry Zuka, thank you for your shoulder to cry on and your constant encouragement. It has been a delight working with you.