You Girls Stay Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vintage Or Classic

Dates for the Diary 2012 June 16-17th Vintage Parasol Pietenpol Club and Bicester Weekend VAC 30th International Rally VAC Bembridge www.vintageaircraftclub.org.ukwww.vintageaircraftclub.org.uk IssueIssue 3838 SummerSummer 20122012 July 1st International Rally VAC Bembridge August 4th-5th Stoke Golding Stake SG Stoke Golding Out 11th-12th International Luscombe Oaksey Park Luscombe Rally 18th-19th International Moth dHMC Belvoir Castle Rally 18th-19th Sywell Airshow and Sywell Sywell Vintage Fly-In 31st LAA Rally LAA Sywell September 1st - 2nd LAA Rally LAA Sywell October 6th / 7th MEMBERS ONLY EVENT 13th VAC AGM VAC Bicester 28th All Hallows Rally VAC Leicester Dates for the Diary 2013 January 20th Snowball Social VAC Sywell February 10th Valentine Social VAC TBA VA C March 9th Annual Dinner VAC Littlebury, Bicester Spring Rally Turweston VAC April 13th Daffodil Rally VAC Fenland The Vintage Aircraft Club Ltd (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Registered Address: Winter Hills Farm, Silverstone, Northants, NN12 8UG Registered in England No 2492432 The Journal of the Vintage Aircraft Club VAC Honorary President D.F.Ogilvy. OBE FRAeS Chairman’s Notes Vintage & Classic ne recent comment summed it up perfectly. “If this Pietenpol builders. The tenth share, which has been given VAC Committee drought goes on much longer, I’ll have to buy some by John to the UK Pietenpol Club and is held in Trust by O new wellies!” the Chairman, will each year be offered to a suitable Chairman Steve Slater 01494-776831 Summer 2012 recipient, who pays a proportion of running and insurance [email protected] Hopefully, by the time you read this, the winds will have costs in return for being allowed to fly the aeroplane. -

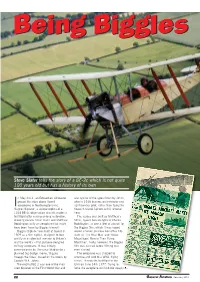

Being Biggles Biggles

BeingBeing Biggles Biggles Steve Slater tells the story of a BE-2c which is not quite 100 years old but has a history of its own n May 2011, an Edwardian silhouette was typical of the types flown by Johns, graced the skies above Sywell who in 1918 became an instructor and Iaerodrome in Northamptonshire. light bomber pilot, rather than flying the ‘Biggles Biplane’, a unique replica of a Sopwith Camel fighters of his fictional 1914 BE-2c observation aircraft, made its hero. first flight after a six-year-long restoration, The replica was built by Matthew’s allowing owners Steve Slater and Matthew father, Sywell-based engineer Charles Boddington to fly an aeroplane that might Boddington, as one a fleet of aircraft for have been flown by Biggles himself. the Biggles film, which it was hoped ‘Biggles Biplane’ was built at Sywell in would emulate previous box office hits 1969 as a film replica, designed to look such as ‘The Blue Max’ and ‘Those and fly in an identical manner to Britain’s – Magnificent Men in Their Flying and the world’s – first purpose-designed Machines’. Sadly, however, the Biggles military aeroplane. It was initially film was canned before filming was commissioned by Universal Studios for a even started. planned big-budget movie, ‘Biggles The aeroplane was shipped to Sweeps the Skies’, based on the books by America and sold to a WW1 ‘flying Captain W.E. Johns. circus’. It made its last flight in the The original BE-2 was one of the most- USA on June 14th 1977. -

Airpilotjune 2018 ISSUE 27

2 AirPilot JUNE 2018 ISSUE 27 RAF ISSUE Centenar y Diary JUNE 2018 AI R PILOT 14th General Purposes & Finance Committee Cutlers’ Hall 25th Election of Sheriffs Guildhall THE HONOURABLE 28th T&A Committee Dowgate Hill House COMPANY OF AIR PILOTS incorporating Air Navigators JULY 2018 12th Benevolent Fund Dowgate Hill House PATRON : 12th ACEC Dowgate Hill House His Royal Highness 16th Summer Supper Watermen’s Hall The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh KG KT 16th Instructors’ Working Group Dowgate Hill House 19th General Purposes & Finance Committee Dowgate Hill House GRAND MASTER : 19th Court Cutlers’ Hall His Royal Highness The Prince Andrew Duke of York KG GCVO MASTER : VISITS PROGRAMME Captain Colin Cox FRAeS Please see the flyers accompanying this issue of Air Pilot or contact Liveryman David Curgenven at [email protected]. CLERK : These flyers can also be downloaded from the Company's website. Paul J Tacon BA FCIS Please check on the Company website for visits that are to be confirmed. Incorporated by Royal Charter. A Livery Company of the City of London. PUBLISHED BY : GOLF CLUB EVENTS The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Please check on Company website for latest information Dowgate Hill House, 14-16 Dowgate Hill, London EC4R 2SU. EDITOR : Paul Smiddy BA (Econ), FCA EMAIL: [email protected] FUNCTION PHOTOGRAPHY : Gerald Sharp Photography View images and order prints on-line. TELEPHONE: 020 8599 5070 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.sharpphoto.co.uk PRINTED BY: Printed Solutions Ltd 01494 478870 Except where specifically stated, none of the material in this issue is to be taken as expressing the opinion of the Court of the Company. -

From Buchan to Johns: Thematic Variety in Imperial Adventure Fiction

Academiejaar 2008-2009 From Buchan to Johns: Thematic Variety in Imperial Adventure Fiction Promotor: Dr. Kate Macdonald Masterproef voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte voor het verkrijgen van de graad van Master in de taal- en letterkunde: Engels door Kevin Denoyette Denoyette 1 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I should like to thank Dr. Kate Macdonald for her unwavering support, guidance, and – above all – patience throughout this project. She has been graceful in assisting me as I clumsily encroached on her area of expertise, provided erudite commentary whenever it was needed, and I could not have asked for a better mentor. Secondly, I feel obliged to briefly mention my elephant man, Mark Lillas, for his persistent motivation through the summer months and his enthusiastic – albeit limited – proofreading. Denoyette 2 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................... 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1. THE ADVENTURE NOVEL: RISE AND RECEPTION .............................................................................. 4 1.1 AN EMERGING READERSHIP .......................................................................................................................... -

Conventional Weapons

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 45 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2009 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group Windrush House Avenue Two Station Lane Witney OX28 4XW 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman FRAeS Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore G R Pitchfork MBE BA FRAes *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain A J Byford MA MA RAF *Wing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS RFC BOMBS & BOMBING 1912-1918 by AVM Peter Dye 8 THE DEVELOPMENT OF RAF BOMBS, 1919-1939 by 15 Stuart Hadaway RAF BOMBS AND BOMBING 1939-1945 by Nina Burls 25 THE DEVELOPMENT OF RAF GUNS AND 37 AMMUNITION FROM WORLD WAR 1 TO THE -

The Life and Politics of David Widgery David Renton

The Life and Politics of David Widgery David Renton David Widgery (1947-1992) was a unique figure on the British left. Better than any one else, his life expressed the radical diversity of the 1968 revolts. While many socialists could claim to have played a more decisive part in any one area of struggle - trade union, gender or sexual politics, radical journalism or anti- racism - none shared his breadth of activism. Widgery had a remarkable abili- ty to "be there," contributing to the early debates of the student, gay and femi- nist movements, writing for the first new counter-cultural, socialist and rank- and-file publications. The peaks of his activity correspond to the peaks of the movement. Just eighteen years old, Widgery was a leading part of the group that established Britain's best-known counter-cultural magazine Oz. Ten years later, he helped to found Rock Against Racism, parent to the Anti-Nazi League, and responsible for some of the largest events the left has organised in Britain. RAR was the left's last great flourish, before Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, and the movement entered a long period of decline, from which even now it is only beginning to awake. David Widgery was a political writer. Some of the breadth of his work can be seen in the range of the papers for which he wrote. His own anthology of his work, compiled in 1989 includes articles published in City Limits, Gay Left, INK, International Socialism, London Review of Books, Nation Review, New Internationalist, New Socialist, New Society, New Statesman, Oz, Radical America, Rank and File Teacher,Socialist Worker, Socialist Review, Street Life, Temporary Hoarding, Time Out and The Wire.' Any more complete list would also have to include his student journalism and regular columns in the British Medical Journal and the Guardian in the 1980s. -

W E Johns and Biggles : the Reality and the Legend by Philip L Scowcroft

Occasional Paper 2nd Series No. 343 W E Johns And Biggles : The Reality and The Legend By Philip L Scowcroft William Earl Johns (1893-1968), a children’s writer and journalist, whose hobbies were shooting and fishing, was born in Hertfordshire. When the Great War broke out, he joined up in the Norfolk Yeomanry and served with it at Gallipoli and later with the Machine Gun Corps at Salonika. He transferred to the RFC in 1917, was commissioned as a pilot and joined 55 Squadron, flying DH4s. he was shot down, wounded and taken prisoner in September 1918. He was tried and condemned to death for indiscriminate bombing of civilians (rather like the pot calling the kettle black for the Germans to do that). He was reprieved because of the likelihood of an armistice; there was still time for him to attempt escape from his prisoner of war camp before 11 November 1918. Johns remained in the RAF post-war and was promoted Flying Officer in 1920, being demobilised in 1927 after flying in RAF displays. He became an aviation illustrator, in 1932 he became founder editor of the monthly periodical Popular Flying which introduced the fictional airman Biggles, first in a collection “The Camels Are Coming” (doubtless after the iconic fighter the Sopwith Camel). By the date of his death, Johns had written 102 books involving Biggles showing his hero as a freelance airman, then as a RAF Second War Squadron Leader, fighting in the Battle of Britain in Spitfire Parade (to be historically accurate the title should be “Hurricane Parade” as there were two Hurricanes to every Spitfire in the Battle) and post-war as Sgt Bigglesworth CID of Scotland Yard. -

JILLENE BYDDER University of Waikato Library Better Than Biggles: Michael Annesley's 'Lawrie Fenton' Spy Thrillers. ABST

Peer Reviewed Proceedings: 6th Annual Conference, Popular Culture Australia, Asia and New Zealand (PopCAANZ), Wellington 29 June – 1 July, 2015, pp. 1-12. ISBN: 978-0-473-34578-5. © 2015 JILLENE BYDDER University of Waikato Library Better than Biggles: Michael Annesley’s ‘Lawrie Fenton’ spy thrillers. ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Captain F.A.M. Webster, the athlete, athletics coach and author who F.A.M. Webster lived from 1886 to 1949, wrote a series of fifteen spy thrillers under the Spy thrillers pseudonym of Michael Annesley. His hero, Lawrie Fenton, is a lively and Michael laid-back secret agent for the fictional Intelligence Branch of the (British) Annesley Foreign Office. The books were published between 1935 and 1950, and Lawrie Fenton the series is important because of its European settings, analyses of The Great Game contemporary politics, insights into contemporary points of view, and snapshots of events and places. Fenton was a new and exciting hero for his times. The paper establishes Webster’s unrecognized but important influence on the development of the spy thriller. The photographs are from the Webster family collection. MICHAEL ANNESLEY = F.A.M. WEBSTER Frederick Annesley Michael Webster was born on 27 June 1886. He was an athlete who started his long involvement with British athletics and the Olympic movement by reporting on the London Olympics in 1908. He originated the idea of the Amateur Field Events Association in 1910, was the English javelin throwing champion in 1911 and 1923 and began his writing career with a book called Olympian Field Events: Their History and Practice (Webster 1913). -

Study 1 – Control Parable Condition

Study 1 – Control Parable Condition Once upon a time there was a hare who, boasting how he could run faster than anyone else, was forever teasing tortoise for its slowness. Then one day, the irate tortoise answered back: "Who do you think you are? There's no denying you're swift, but even you can be beaten!" The hare squealed with laughter. "Beaten in a race? By whom? Not you, surely! I bet there's nobody in the world that can win against me, I'm so speedy. Now, why don't you try?" Annoyed by such bragging, the tortoise accepted the challenge. A course was planned, and the next day at dawn they stood at the starting line. The hare yawned sleepily as the meek tortoise trudged slowly off. When the hare saw how painfully slow his rival was, he decided, half asleep on his feet, to have a quick nap. "Take your time!" he said. "I'll have forty winks and catch up with you in a minute." The hare woke with a start from a fitful sleep and gazed round, looking for the tortoise. But the creature was only a short distance away, having barely covered a third of the course. Breathing a sigh of relief, the hare decided he might as well have breakfast too, and off he went to munch some cabbages he had noticed in a nearby field. But the heavy meal and the hot sun made his eyelids droop. With a careless glance at the tortoise, now halfway along the course, he decided to have another snooze before flashing past the winning post. -

The Journal of the Vintage Aircraft Club VAC Honorary President D.F.Ogilvy

Dates for the Diary 2012 www.vintageaircraftclub.org.ukwww.vintageaircraftclub.org.uk IssueIssue 3636 WinterWinter 20112011 Saturday 21st January IssueIssue 3636 WinterWinter 20112011 Snowball Rally - Sywell (Incl. Biggles Biplane restoration hangar tour) Sunday 12th February Valentine Rally - Old Sarum Saturday 10th March Annual Dinner - Littlebury Hotel, Bicester Sunday 25th March Spring Meeting - Turweston Saturday 14th April Daffodil Rally - Fenland July - Date to be confirmed International Fly-In—Bembridge Isle of Wight 4th/5th August Members only event 6th / 7th October Members Only Saturday 13th October Annual General Meeting and Members Fly-In - TBC VA C Saturday 27th October All Hallows - Leicester The Vintage Aircraft Club Ltd (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Registered Address: Winter Hills Farm, Silverstone, Northants, NN12 8UG Registered in England No 2492432 The Journal of the Vintage Aircraft Club VAC Honorary President D.F.Ogilvy. OBE FRAeS Chairman’s Notes VAC Committee Vintage & Classic ello and first of all, to those who joined us at the Chairman Steve Slater 01494-776831 Winter 2008 H AGM at Old Warden, thank you for electing me as [email protected] the Club’s new chairman. Contents Vice Chairman Paul Loveday 01327-351556 Thank you too, to John Broad, who for more than a decade Newsletter Editor & e-mail [email protected] has been much more than the VAC chairman, he has been Booking in Team Page Title an indefatigable supporter of light aviation in general. I am delighted I can still rely on his advice. Secretary & Sandy Fage 01327-858138 1 Who’s Who Treasurer e-mail [email protected] 2 Chairman’s Notes Indeed we are all lucky to be able to rely on so many club Editor’s Column stalwarts, some on the VAC Committee, others (and their Membership Carol Loveday 01327-351556 3 Introducing the new aeroplanes too!) who simply enhance the club by regularly Secretary e-mail [email protected] Chairman. -

Biplanes and Bombsights: British Bombing in Word War I

Biplanes and Bombsights British Bombing in World War I George K. WMiams Air University Press Maxell Air Force Base, Alabama May 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data Williams. George Kent, 1944- Biplanes and bombsights : British Bombing in World War I / George Kent Williams. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ' 1. World War, 1914-1918-Aerial operations, British. 2. Bombers-Great Britain. I. ' Title. D602.W48 1999 940 .4'4941-dc21 ~9-26205 CIP Disclaimer opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressedor implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release : distribution unlimited. e il Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . .. ' , ix INTRODUCTION . : . 1 - NO. 3 WING ROYAL NAVAL AIR SERVICE (JULY 1916-MAY 1917) . .. ... 30f Notes . 2 BRITISH BOMBING BEGINS . 35 Notes . .. 67 3 41ST WING ROYAL FLYING CORPS (JUNE 1917-JANUARY 1918) . 73 Notes . .. 125 4 . EIGHTH BRIGADE AND INDEPENDENT FORCE (FEBRUARY-NOVEMBER 1918) . 133 Notes . 180 5 EIGHTH BRIGADE AND INDEPENDENT FORCE OPERATIONS . 189 Notes . 231 6 POSTWAR ASSESSMENTS . 239 Notes . 264 APPENDIX . 269 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 289 INDEX . 299 iii Illustrations Table Page 1 'Battle Casualties, Night Squadrons, June-November 1918 . 210 Photographs Handley Page . 9 DeHavilland 4B . 43 Me . 63 Foreword This study measures wartime claims against actual results of the British bombing campaign against Germany in the Great War. Components of the' Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), the Royal Flying Corps (RFC); and the Royal Air Force (RAF) conducted bombing raids between July 1916 and the Armistice. -

Biggles Goes to War Free Download

BIGGLES GOES TO WAR FREE DOWNLOAD W. E. Johns | 192 pages | 06 Sep 1996 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780099634416 | English | London, United Kingdom Biggles Goes to War Seller Inventory Expedited UK Delivery Available. Thanks for telling us about the problem. The cultural and social world of Biggles whether in the s or some earlier period does not persist completely unchanged through the whole series — for instance, in an early book, the evidence points to an English nobleman as the perpetrator but Biggles Biggles Goes to War this out of hand as the gentry would never commit a Biggles Goes to War in a later novel, one of the gentry is the Biggles Goes to War. Later in the evening, Biggles and co. Postage is reduced on multiple orders. Maltovia needs Biggles to help set up its air force. A book that every boy should read. The band of intrepid Britishers is much encouraged by a clandestine visit from the head of state, Princess Mariana, who also happens to be young and beautiful. It turns out to be a new aircraft for the Lovitzna Air Force. May 02, Jacob Quinn rated it Biggles Goes to War liked it. The blatant message of 'what those effete foreigners and women in positions of authority need is a Biggles' is, well, blatant. If they have a strong handshake, they are good. The group takes on criminals who have taken to the air, both at home in Britain and around the globe, as well as battling opponents behind the Iron Curtain. Biggles, Ginger and the Count have to struggle to the border and this includes being chased by wolves and Biggles Goes to War a river under fire.