Is It a Fallacy to Believe in the Hot Hand in the NBA Three-Point Contest?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribute to Champions

HLETIC C AT OM M A IS M S O I C O A N T Tribute to Champions May 30th, 2019 McGavick Conference Center, Lakewood, WA FEATURING CONNELLY LAW OFFICES EXCELLENCE IN OFFICIATING AWARD • Boys Basketball–Mike Stephenson • Girls Basketball–Hiram “BJ” Aea • Football–Joe Horn • Soccer–Larry Baughman • Softball–Scott Buser • Volleyball–Peter Thomas • Wrestling–Chris Brayton FROSTY WESTERING EXCELLENCE IN COACHING AWARD Patty Ley, Cross Country Coach, Gig Harbor HS Paul Souza, Softball & Volleyball Coach, Washington HS FIRST FAMILY OF SPORTS AWARD The McPhee Family—Bill and Georgia (parents) and children Kathy, Diane, Scott, Colleen, Brad, Mark, Maureen, Bryce and Jim DOUG MCARTHUR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Willie Stewart, Retired Lincoln HS Principal Dan Watson, Retired Lincoln HS Track Coach DICK HANNULA MALE & FEMALE AMATEUR ATHLETE OF THE YEAR AWARD Jamie Lange, Basketball and Soccer, Sumner/Univ. of Puget Sound Kaleb McGary, Football, Fife/Univ. of Washington TACOMA-PIERCE COUNTY SPORTS HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES • Baseball–Tony Barron • Basketball–Jim Black, Jennifer Gray Reiter, Tim Kelly and Bob Niehl • Bowling–Mike Karch • Boxing–Emmett Linton, Jr. and Bobby Pasquale • Football–Singor Mobley • Karate–Steve Curran p • Media–Bruce Larson (photographer) • Snowboarding–Liz Daley • Swimming–Dennis Larsen • Track and Field–Pat Tyson and Joel Wingard • Wrestling–Kylee Bishop 1 2 The Tacoma Athletic Commission—Celebrating COMMITTEE and Supporting Students and Amateur Athletics Chairman ������������������������������Marc Blau for 76 years in Pierce -

Interview with Craig Hodges During His Ten Years in the NBA, Craig

Interview with Craig Hodges During his ten years in the NBA, Craig Hodges achieved many great successes as a player, winning two NBA Finals championships with the Chicago Bulls and three consecutive Three-Point Contest titles at the NBA’s All-Star Weekend. As an activist, he fought for and continues to fight for many of the most vulnerable in American society. The following is a transcript of Craig Hodges’ interview with Brian Burmeister on May 5, 2017. BB: Hi, this is Brian Burmeister with the Sport Literature Association. Today I’m joined by Craig Hodges, one of the greatest three-point shooters in NBA history. He recently wrote and released the book Long Shot: The Triumphs and Struggles of an NBA Freedom Fighter. ThanK you so much for joining me here today, Craig. CH: Appreciate it, man. BB: The booK itself really explores your whole life, from your upbringing, through your college and NBA careers, all the way up through today. Much of the early part of the book focuses on your upbringing in Chicago Heights. Would you be willing to talK us through the role your family and the community itself played in shaping your mind and your values. CH: I appreciate it man. Once again just thanKing God for an opportunity to speaK about things that have been pertinent in my life. And nothing more pertinent than the family and the community that I was raised in. I wouldn’t change it for anything in the world. Knowing that it was truly a village. To Know that everybody cared. -

MEDIA INFORMATION to the MEDIA: Welcome to the 30Th Season of Kings Basketball in Sacramento

MEDIA INFORMATION TO THE MEDIA: Welcome to the 30th season of Kings basketball in Sacramento. The Kings media relations department will do everything possible to assist in your coverage of the club during the 2014-15 NBA season. If we can ever be of assistance, please do not hesitate to contact us. In an effort to continue to provide a professional working environment, we have established the following media guidelines. CREDENTIALS: Single-game press credentials can be reserved by accredited media members via e-mail (creden- [email protected]) until 48 hours prior to the requested game (no exceptions). Media members covering the Kings on a regular basis will be issued season credentials, but are still required to reserve seating for all games via email at [email protected] to the media relations office by the above mentioned deadline. Credentials will allow working media members entry into Sleep Train Arena, while also providing reserved press seating, and access to both team locker rooms and the media press room. In all cases, credentials are non-transferable and any unauthorized use will subject the bearer to ejection from Sleep Train Arena and forfeiture of the credential. All single-game credentials may be picked-up two hours in advance of tip-off at the media check-in table, located at the Southeast security entrance of Sleep Train Arena. PRESS ROOM: The Kings press room is located on the Southeast side of Sleep Train Arena on the operations level and will be opened two hours prior to game time. Admittance/space is limited to working media members with credentials only. -

2008-09 Playoff Guide.Pdf

▪ TABLE OF CONTENTS ▪ Media Information 1 Staff Directory 2 2008-09 Roster 3 Mitch Kupchak, General Manager 4 Phil Jackson, Head Coach 5 Playoff Bracket 6 Final NBA Statistics 7-16 Season Series vs. Opponent 17-18 Lakers Overall Season Stats 19 Lakers game-By-Game Scores 20-22 Lakers Individual Highs 23-24 Lakers Breakdown 25 Pre All-Star Game Stats 26 Post All-Star Game Stats 27 Final Home Stats 28 Final Road Stats 29 October / November 30 December 31 January 32 February 33 March 34 April 35 Lakers Season High-Low / Injury Report 36-39 Day-By-Day 40-49 Player Biographies and Stats 51 Trevor Ariza 52-53 Shannon Brown 54-55 Kobe Bryant 56-57 Andrew Bynum 58-59 Jordan Farmar 60-61 Derek Fisher 62-63 Pau Gasol 64-65 DJ Mbenga 66-67 Adam Morrison 68-69 Lamar Odom 70-71 Josh Powell 72-73 Sun Yue 74-75 Sasha Vujacic 76-77 Luke Walton 78-79 Individual Player Game-By-Game 81-95 Playoff Opponents 97 Dallas Mavericks 98-103 Denver Nuggets 104-109 Houston Rockets 110-115 New Orleans Hornets 116-121 Portland Trail Blazers 122-127 San Antonio Spurs 128-133 Utah Jazz 134-139 Playoff Statistics 141 Lakers Year-By-Year Playoff Results 142 Lakes All-Time Individual / Team Playoff Stats 143-149 Lakers All-Time Playoff Scores 150-157 MEDIA INFORMATION ▪ ▪ PUBLIC RELATIONS CONTACTS PHONE LINES John Black A limited number of telephones will be available to the media throughout Vice President, Public Relations the playoffs, although we cannot guarantee a telephone for anyone. -

2007-08 Friar Basketball Charles Burch Charles Burch Career Game-By-Game

Quick Facts 2007-08 Friar Basketball PROVIDENCE COLLEGE MEN'S BASKETBALL PROSPECTUS GENERAL INFORMATION HEAD COACH: Tim Welsh ALMA MATER/YEAR: Potsdam State (1984) LOCATION: Providence, RI 02918 RECORD AT PC/SEASONS: 145/127 (66-80 Big East)/9 seasons FOUNDED: 1917 OVERALL RECORD/SEASONS: 215-149/12 seasons ENROLLMENT: 3,912 NCAA TOURN. RECORD: 0-3/3 appearances (1998, 2001, 2004) NICKNAME: Friars BEST TIME TO REACH COACH: Contact SID COLORS: Black, White and Silver (PMS 877) ASSOC. HEAD COACH: Steve DeMeo ARENA: Dunkin' Donuts Center (10,800) ASSISTANT COACHES: Vince Cautero AFFILIATION: NCAA Division I Allen Griffin CONFERENCE: BIG EAST DIRECTOR OF BASKETBALL OPER.: Kevin Kurbec PRESIDENT: Reverend Brian J. Shanley, O.P. GRADUATE ASSISTANT: Hank Plona ATHLETIC DIRECTOR: Robert Driscoll BASKETBALL OFFICE: (401) 865-2266 ATHLETIC DEPT. PHONE: (401) 865-2500 BASKETBALL SECRETARY: Susan Gaber TICKET INFORMATION: (401) 865-GOPC ATHLETIC TRAINER: Ben Rohde STRENGTH COACH: Kenneth White TEAM INFORMATION HISTORY 2006-07 RECORD: 18-13 (H: 16-3, A: 2-8, N: 0-2) FIRST YEAR OF BASKETBALL: 1926-27 CONFERENCE RECORD: 8-8 (H: 6-2, A: 2-6) OVERALL ALL-TIME RECORD: 1240-808 (.605) 10th BIG EAST YEARS IN NCAA TOURN./LAST: 15 times/2004 BIG EAST Tournament First Round, Pacific FINAL RANKING LAST SEASON (POLL): 78 (RPI) RESULT: Loss, 66-58 PLAYERS RETURNING/LOST: 11/2 YEARS IN NIT/LAST: 17 times/2007 STARTERS RETURNING/LOST: 4/1 First Round, Bradley NEWCOMERS: 4 RESULT: Loss, 90-78 OT RETURNING PLAYERS (11) 2006-07 NO NAME PTS/REB POS HT WT CL 4 Sharaud Curry 15.9/2.8 G 5-10 170 Jr. -

History All-Time Coaching Records All-Time Coaching Records

HISTORY ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS REGULAR SEASON PLAYOFFS REGULAR SEASON PLAYOFFS CHARLES ECKMAN HERB BROWN SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT LEADERSHIP 1957-58 9-16 .360 1975-76 19-21 .475 4-5 .444 TOTALS 9-16 .360 1976-77 44-38 .537 1-2 .333 1977-78 9-15 .375 RED ROCHA TOTALS 72-74 .493 5-7 .417 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1957-58 24-23 .511 3-4 .429 BOB KAUFFMAN 1958-59 28-44 .389 1-2 .333 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1959-60 13-21 .382 1977-78 29-29 .500 TOTALS 65-88 .425 4-6 .400 TOTALS 29-29 .500 DICK MCGUIRE DICK VITALE SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT PLAYERS 1959-60 17-24 .414 0-2 .000 1978-79 30-52 .366 1960-61 34-45 .430 2-3 .400 1979-80 4-8 .333 1961-62 37-43 .463 5-5 .500 TOTALS 34-60 .362 1962-63 34-46 .425 1-3 .250 RICHIE ADUBATO TOTALS 122-158 .436 8-13 .381 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT CHARLES WOLF 1979-80 12-58 .171 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT TOTALS 12-58 .171 1963-64 23-57 .288 1964-65 2-9 .182 SCOTTY ROBERTSON REVIEW 18-19 TOTALS 25-66 .274 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1980-81 21-61 .256 DAVE DEBUSSCHERE 1981-82 39-43 .476 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1982-83 37-45 .451 1964-65 29-40 .420 TOTALS 97-149 .394 1965-66 22-58 .275 1966-67 28-45 .384 CHUCK DALY TOTALS 79-143 .356 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1983-84 49-33 .598 2-3 .400 DONNIE BUTCHER 1984-85 46-36 .561 5-4 .556 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1985-86 46-36 .561 1-3 .250 RE 1966-67 2-6 .250 1986-87 52-30 .634 10-5 .667 1967-68 40-42 .488 2-4 .333 1987-88 54-28 .659 14-9 .609 CORDS 1968-69 10-12 .455 1988-89 63-19 .768 15-2 .882 TOTALS 52-60 .464 2-4 .333 -

2012-13 Past & Present HITS Checklist Basketball

2012-13 Past & Present HITS Checklist Basketball Player Set # Team Seq # Arnett Moultrie Signatures 234 76ers Charles Jenkins Signatures 207 76ers Darryl Dawkins Signatures 98 76ers Dikembe Mutombo Signatures 124 76ers Dolph Schayes Modern Marks 31 76ers Hal Greer Signatures 116 76ers Jason Richardson Signatures 138 76ers Jeremy Pargo Signatures 220 76ers Julius Erving Hall Marks 17 76ers Lavoy Allen Signatures 154 76ers Spencer Hawes Dual Jerseys 5 76ers Spencer Hawes Dual Jerseys Prime 5 76ers 25 Bill Walton Hall Marks 15 Blazers Calvin Natt Elusive Ink 40 Blazers Clyde Drexler Dual Jerseys 9 Blazers Clyde Drexler Dual Jerseys Prime 9 Blazers 25 Clyde Drexler Hall Marks 20 Blazers Isaiah Rider Elusive Ink 37 Blazers J.J. Hickson Signatures 134 Blazers LaMarcus Aldridge Gamers 21 Blazers LaMarcus Aldridge Gamers Prime 21 Blazers 10 Meyers Leonard Signatures 233 Blazers Nolan Smith Signatures 212 Blazers Terry Porter Elusive Ink 30 Blazers Victor Claver Signatures 185 Blazers Will Barton Signatures 152 Blazers Ben Gordon Modern Marks 5 Bobcats Ben Gordon Signatures 149 Bobcats Bismack Biyombo Signatures 222 Bobcats Jeff Taylor Signatures 199 Bobcats Kemba Walker Signatures 190 Bobcats Michael Kidd-Gilchrist Modern Marks 39 Bobcats Michael Kidd-Gilchrist Signatures 230 Bobcats Tyrus Thomas Dual Jerseys 13 Bobcats 99 Tyrus Thomas Dual Jerseys Prime 13 Bobcats 25 Ersan Ilyasova Signatures 140 Bucks Gustavo Ayon Signatures 247 Bucks John Henson Signatures 211 Bucks Moses Malone Signatures 121 Bucks Sidney Moncrief Signatures 107 Bucks 2012-13 Past & Present HITS Checklist Basketball Player Set # Team Seq # Artis Gilmore Hall Marks 11 Bulls Artis Gilmore Modern Marks 30 Bulls B.J. -

Dallas Mavericks (42-30) (3-3)

DALLAS MAVERICKS (42-30) (3-3) @ LA CLIPPERS (47-25) (3-3) Game #7 • Sunday, June 6, 2021 • 2:30 p.m. CT • STAPLES Center (Los Angeles, CA) • ABC • ESPN 103.3 FM • Univision 1270 THE 2020-21 DALLAS MAVERICKS PLAYOFF GUIDE IS AVAILABLE ONLINE AT MAVS.COM/PLAYOFFGUIDE • FOLLOW @MAVSPR ON TWITTER FOR STATS AND INFO 2020-21 REG. SEASON SCHEDULE PROBABLE STARTERS DATE OPPONENT SCORE RECORD PLAYER / 2020-21 POSTSEASON AVERAGES NOTES 12/23 @ Suns 102-106 L 0-1 12/25 @ Lakers 115-138 L 0-2 #10 Dorian Finney-Smith LAST GAME: 11 points (3-7 3FG, 2-2 FT), 7 rebounds, 4 assists and 2 steals 12/27 @ Clippers 124-73 W 1-2 F • 6-7 • 220 • Florida/USA • 5th Season in 42 minutes in Game 6 vs. LAC (6/4/21). NOTES: Scored a playoff career- 12/30 vs. Hornets 99-118 L 1-3 high 18 points in Game 1 at LAC (5/22/21) ... hit GW 3FG vs. WAS (5/1/21) 1/1 vs. Heat 93-83 W 2-3 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG ... DAL was 21-9 during the regular season when he scored in double figures, 1/3 @ Bulls 108-118 L 2-4 6/6 9.0 6.0 2.2 1.3 0.3 38.5 1/4 @ Rockets 113-100 W 3-4 including 3-1 when he scored 20+. 1/7 @ Nuggets 124-117* W 4-4 #6 LAST GAME: 7 points, 5 rebounds, 3 assists, 3 steals and 1 block in 31 1/9 vs. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Mike Glenn

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Mike Glenn PERSON Glenn, Mike, 1955- Alternative Names: Mike Glenn; Life Dates: September 10, 1955- Place of Birth: Rome, Georgia, USA Work: Snellville, GA Occupations: Television Sports Commentator; Basketball Player Biographical Note NBA guard and television sports analyst, Michael Theodore “Stinger” Glenn was born on September 10, 1955 in Rome, Georgia. Growing up in Cave Springs, Georgia, his father taught and coached at the Georgia School for the Deaf while Glenn’s mother taught him at E.S. Brown Elementary School. Glenn became the top rated high school basketball player in Georgia, averaging 30 points per game when he graduated from Rome’s Coosa High School, third in his class, in 1973. An All Missouri Valley Conference college basketball Rome’s Coosa High School, third in his class, in 1973. An All Missouri Valley Conference college basketball player, Glenn graduated from Southern Illinois University with honors and a B.S. degree in mathematics in 1977. Drafted twenty-third overall by the NBA’s Chicago Bulls in 1977, Glenn broke his neck in an auto accident and was released from the team. Later that year, he was signed by the NBA’s Buffalo Braves (now the Los Angeles Clippers). In 1978, Glenn signed with the New York Knicks, playing with Ray Williams, Michael Ray Richardson and the legendary Earl “The Pearl” Monroe. Known for his shooting accuracy, Glenn was named “Stinger” by his teammates. In New York, Glenn attended graduate business classes at St. John’s University and Baruch College and earned his stockbroker’s license. -

Extract Interesting Skyline Points in High Dimension

Extract Interesting Skyline Points in High Dimension Gabriel Pui Cheong Fung1,WeiLu2,3,JingYang3, Xiaoyong Du2,3, and Xiaofang Zhou1 1 School of ITEE, The University of Queensland, Australia {g.fung,zxf}@uq.edu.au 2 Key Labs of Data Engineering and Knowledge Engineering, Ministry of Education, China 3 School of Information, Renmin University of China, China {uqwlu,jyang,duyong}@ruc.edu.cn Abstract. When the dimensionality of dataset increases slightly, the number of skyline points increases dramatically as it is usually unlikely for a point to perform equally good in all dimensions. When the dimensionality is very high, almost all points are skyline points. Extract interesting skyline points in high di- mensional space automatically is therefore necessary. From our experiences, in order to decide whether a point is an interesting one or not, we seldom base our decision on only comparing two points pairwisely (as in the situation of skyline identification) but further study how good a point can perform in each dimension. For example, in scholarship assignment problem, the students who are selected for scholarships should never be those who simply perform better than the weak- est subjects of some other students (as in the situation of skyline). We should select students whose performance on some subjects are better than a reasonable number of students. In the extreme case, even though a student performs outstand- ing in just one subject, we may still give her scholarship if she can demonstrate she is extraordinary in that area. In this paper, we formalize this idea and propose k k a novel concept called k-dominate p-coreskyline(Cp). -

Lebron James Breaks Silence on Darfur 'Human Rights and People's Lives Are in Jeopardy'

LeBron James Breaks Silence on Darfur 'Human Rights and People's Lives Are in Jeopardy' By Shelley Smith May 19, 2008 When LeBron James walked into our makeshift studio at the Four Seasons Hotel in Washington, D.C., we had no idea what the Cleveland Cavaliers' superstar forward was going to say. We had asked for the interview for our "Outside the Lines" story on NBA athletes and political activism, specifically to see if he'd address why he declined to sign then-teammate Ira Newble's letter a year ago condemning China for its role in the genocide in Darfur. At the time Newble presented the letter, James said he didn't have enough information to speak on the issue, let alone sign anything. And he was ripped from coast to coast, by pundits, columnists and social observers. They all characterized James as a greedy, spoiled athlete who cared more about his business interests in China than the slaughter of a reported 400,000 non-Arabs in Darfur. To be sure, China's record on human rights issues was, and remains, a sensitive topic, especially for James' employer, the NBA, which has had its eyes on China for more than 20 years. And then add the pressure of James' $90 million contract with Nike, which has its own designs on the vast LeBron James was criticized for declining to sign a letter of Chinese market. James is so wildly popular protest, circulated by a teammate, over what the letter said there that he already has two China-only was the Chinese government's complicity in the humanitarian marketed shoes and his own museum in crisis in Dafur, Sudan. -

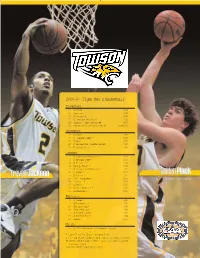

06 MBB Covers.Qxd

2006-07 Tiger Men s Basketball November 13 Hart ford 7:00 16 Samford 7:00 19 @ Kansas # 8:00 21 @ Western Kentucky # 7:00 24 Tennessee Chattanooga ## 8:00 25 Tennessee State/Prairie V iew ## 2:30/5:00 December 1 Vermont 7:00 5 @ W illiam & Mary * 8:00 16 Temple 2:00 20 @ Georgetown (Verizon Center) 7:30 29 W inston-Salem 7:00 January 3 V irginia Commonwealth * 7:00 6 @ Georgia State * 2:00 8 @ Delaware * 7:00 11 George Mason * 7:00 13 @ Virginia Commonwealth * 7:30 15 @ Loyola * 7:00 18 @ Hofstra * 7:00 20 UNC Wilmington * 2:00 24 Delaware * 7:00 27 Hofstra * 4:00 29 @James Madison * 7:00 31 Northeastern * 7:00 February 3 @ Drexel * 4:00 7 @ Northeastern * 7:00 10 Georgia State * 2:00 14 James Madison * 7:00 17 @ Bracket Buster T B D 21 @ Old Dominion * 7:00 24 Drexel * Noon March 2-5 @ C A A Tournament (Richmond Colesium) All Game Times Are Eastern Standard Time # First and Second Rounds, Findlay Toyot a Las Vegas Invit ational ## Championship Round, Findlay Toyot a Las Vegas Invit ational @ Orleans Arena * Colonial Athletic Association games Junior Forward Sean Raboin PlayerPlayer ProfilesProfiles Dennard Abraham 22 DennardSenior Forward · 6-8, 245 lbs. Abraham Owings Mills, Md. · Notre Dame Academy · Sport Studies Major Towsonís big force underneath ... one of the Tigersí In High School: Dennard attended Franklin and captains this season ... showed marked improvement Owings Mills H.S. in Baltimore County before fin- Dennard’s as his junior year progressed.