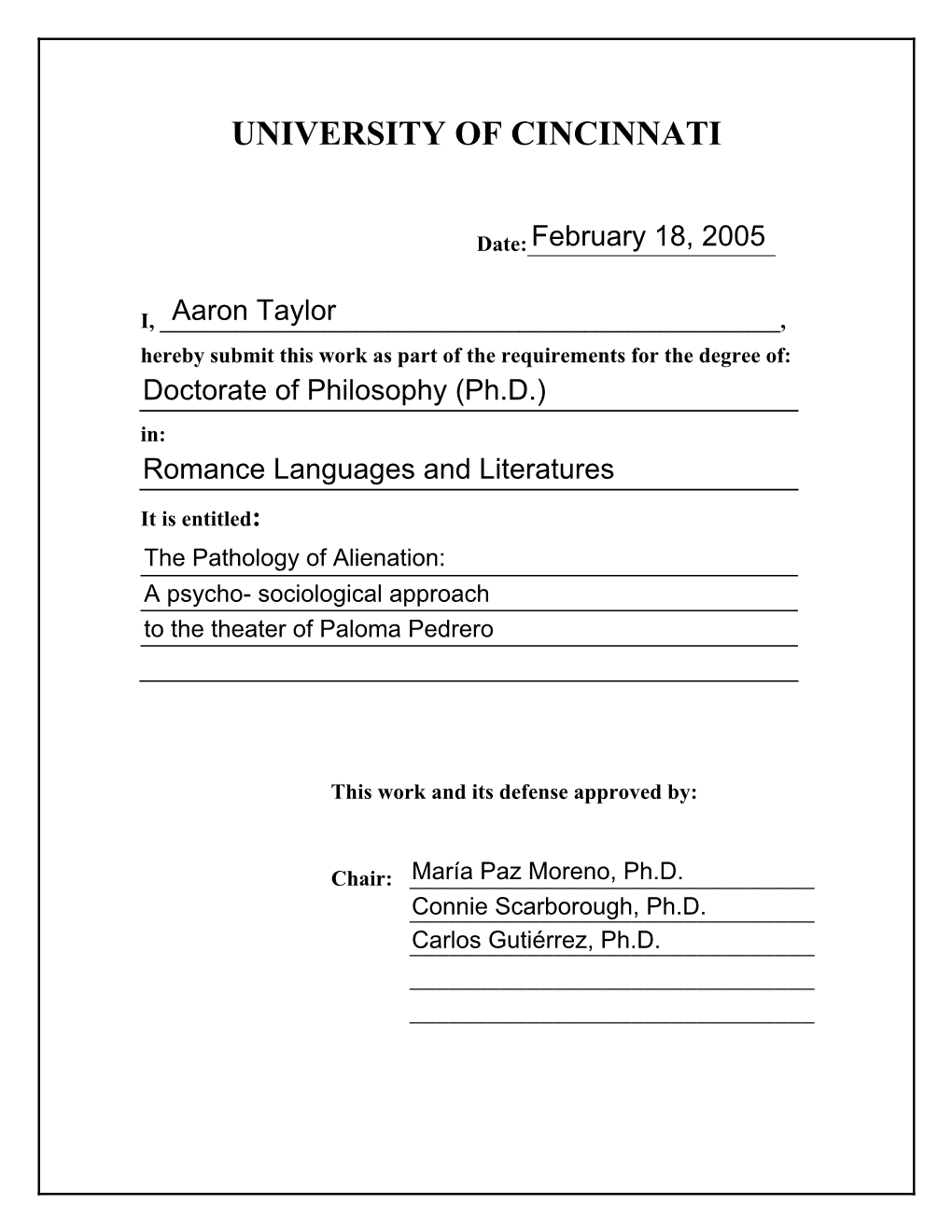

University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Resistencia Como Práctica Que Posibilita La Subjetivación

ANAGRAMAS - UNIVERSIDAD DE MEDELLIN La resistencia como práctica que posibilita la subjetivación. Un acercamiento al concierto-ritual de música de resistencia* Mariana Rebeca Ferrari Violante** Recibido: 2016-08-12 Enviado a pares: 2016-08-23 Aprobado por pares: 2016-09-18 Aceptado: 2016-11-11 DOI: 10.22395/angr.v15n30a7 Resumen En la sociedad actual existe un interés, por parte de los aparatos de poder, de gobernar al ser humano. Sin embargo, también está presente una inquietud genuina en los gobernados de no ser administrados. En este sentido, la búsqueda de estrategias para ejercer resistencia es algo necesario. Esta no es una tarea fácil, pero existe la posibilidad de que el sujeto encuentre en un pequeño pliegue del discurso opresor la oportunidad de resistir y comandar desde sí y para sí su pensamiento, conducta y acciones. La subjetivación, entendida como un proceso por medio del cual un sujeto puede tener acción sobre sí mismo y moldearse bajo sus propios designios, es una de las consecuencias de la resistencia, y en este trabajo la exploramos en un contexto en específico: los conciertos de música de resistencia entendidos como rituales. En esta investigación describimos uno de estos conciertos-rituales tomando en cuenta solo tres elementos: la música de resistencia, el lugar donde se llevan a cabo y los sujetos que asisten. Cada uno de estos componentes posee características particulares que pueden propiciar prácticas de resistencia y, en consecuencia, el proceso de subjetivación. Así pues, el objetivo de este trabajo es explorar brevemente la relación entre la resistencia, la subjetivación y la práctica ética en un contexto específico que es el concierto-ritual. -

Cultura-Popular-Y-Contrahegemonia

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y HUMANIDADES DEPARTAMENTO DE LITERATURA CULTURA POPULAR Y CONTRAHEGEMONÍA EN LAS LÍRICAS DEL RAP CHILENO INDEPENDIENTE Memoria para optar al grado de Magíster en Literatura, mención Hispanoamericana y Chilena Estudiante: Eduardo Asfura Insunza Profesor Guía: Dr. Horst Nitschack Santiago, Chile 2011 EPÍGRAFES Porque el rap es parte / del arte popular, / que no es arte de salón, / es arte marginal; / la voz poblacional, / que es más que ritmo y poesía: / es el soundtrack y el retrato fiel / de nuestro día a día. Andi Portavoz O rapper não possui mitologia nem habita o Parnaso, mas caminha no chão de asfalto da cidade e tenta transformar em canto a matéria vulgar, suja e violenta do cotidiano. Ferreira Gullar 2 DEDICATORIA A Paula, amor que me ilumina. A la memoria de Salvador Asfura Lama, mi padre (1923 – 2011). 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS Agradezco a Paula Jaramillo, por su amor, confianza y consejos; antes, durante y después de la elaboración de este trabajo. Deseo agradecer también a las familias Asfura Insunza y Martínez Jaramillo, por su permanente afecto y preocupación. A mis queridos amigos Nino, Gaby, Marcelo, Sally, Glenda, Cote, Andrea y Roberto, por mantener alejada la tentación de su compañía durante esta temporada de “arresto domiciliario”. De igual modo, agradezco a los profesores del programa de Magíster en Literatura de la Universidad de Chile, por conducirme en esta maravillosa experiencia de conocimiento. De manera especial, al profesor Horst Nitschack, por sus oportunos consejos y orientaciones en el desarrollo de esta investigación. 4 TABLA DE CONTENIDOS Página EPÍGRAFE........................................................................... 2 DEDICATORIA………………………………………………... 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS………………………………………… 4 TABLA DE CONTENIDOS………………………………….. -

Beca Y Eva Dicen Que Se Quieren

BECA Y EVA DICEN QUE SE QUIEREN Premio Leopoldo Alas/ LGTB/ SGAE 2011 Juan Luis Mira Beca y Eva dicen que se quieren Juan Luis Mira Para Carmen y Marisol e Irene y Cris y Charo y Débora y Gu y Roberto y Omar y Martín y Tábata y Josi y Vero y todos los amores posibles e imposibles. Personajes: BECA, alrededor de diecisiete años EVA, lo mismo. Tiempo: hoy. 2 Beca y Eva dicen que se quieren Juan Luis Mira NOTA DEL AUTOR: -BECA y EVA DICEN QUE SE QUIEREN no debe leerse/actuarse como un texto para jóvenes, aunque evidentemente tiene a estos –los grandes olvidados de la escena- como principales destinatarios. -Tanto BECA como EVA deben ser interpretadas por actrices jóvenes que “representen” la edad indicada. -Las dos actrices, además de sus respectivos personajes, se desdoblarán para interpretar la galería de personajes que aparecen en la obra de la forma más natural posible, sin forzar la voz, la actitud o el gesto. Detrás de cada personaje están siempre ellas, y es el texto el que define siempre al personaje y no al revés. -Las escenas pueden leerse o representarse en el orden propuesto o en cualquier otro. El tránsito de una escena a otra debe hacerse de forma fluida y sin interrupciones. 3 Beca y Eva dicen que se quieren Juan Luis Mira Uno. Un mes antes de que acabe el curso. Habitación 302. EVA: ¿Entonces? BECA: ¿Qué? EVA: No me has contestado. BECA: Si ya lo sabes... EVA: No, no lo sé. BECA: Pues claro que lo sabes. -

Q Oprecaricen

“Este fanzine no es un producto del sistema, el precio lo pones tu. Colabora con nosotros si puedes y quieres” eL INSOLENTE Órgano de expresión de la Juventud Comunista de Castilla y León Q nº3 - Marzo - Abril - Mayo 2006 UE NO PRECARICEN la reTbeUlionVesIDJUASTICIA www.jccl.tk inicio INDICE: Lo único que falta.... Pag. 2. Contratas y subcontratas Pag. 3. Editorial/Cita para la reflexión Págs. 4-5. Nepal en la encrucijada Págs. 6-7-8. El problema de la vivienda Pág. 9. Datos a tocateja Págs. 10-11. Cómic: Forges Pág.12. 75º aniversario de la “democracia plena” Pag. 13. Dos años del 11M / Fascismo en Valladolid Pág. 14. Reforma laboral/ Mujer trabajadora hoy Pág. 15. Los estupidos animales de San Glorio Págs. 16-17. Así habló Zaratustra Tomy. Rebelión.org 02-03-06 Págs. 18-19.El Reggaeton ¿Qué son................las CONTRATAS y SUBCONTRATAS? SEGUIMOS CON NUESTRA SECCIÓN “QUE ES...”, EN ESTE NÚMERO ciones y formación profesional totalmente dispares. ACLARAMOS LO QUE SON LAS CONTRATAS Y SUBCONTRATAS, FIGURAS QUE SE DAN MUCHO EN LAS GRANDES EMPRESAS HOY EN DÍA, Y QUE Recurrentemente aparecen las subcontratas como TIENEN MUCHA TRASCENDENCIA COMO EN EL ASUNTO DEL ACCIDENTE protagonistas de aciagos accidentes. Una tragedia que DEL YAKOLEV. ya es estructural, siendo acusadas -salvándose de críti- cas la empresa contratista- de tener trabajadores inex- CONTRATA: Se produce cuando un Empresario realiza pertos o que incumplen las normas de prevención de un contrato civil denominado Contrata con otro empre- accidentes. Este sistema conlleva gran precariedad lab- sario al que se denomina Contratista, para que éste oral y a pesar de ello es un sistema legal de aporte sus propios trabajadores con el fin de auxiliar al explotación, incluido en el Estatuto de los Principal en una determinada obra o servicio. -

Fiesta De Difuntos En" Casablanca La Bella" De Fernando Vallejo

201-216 FIESTA DE DIFUNTOS EN CASABLANCA LA BELLA DE FERNANDO VALLEJO A feast for the dead in Casablanca la bella by Fernando Vallejo María Luisa Martínez Muñoz* Resumen Casablanca la bella (2013) de Fernando Vallejo continúa el diálogo que el narrador sostiene con la muerte en sus textos anteriores. La novela evidencia y despliega las obsesiones del autor a partir de la compra y restauración de Casablanca, antigua casa ubicada en el barrio Laureles, Medellín, y cifra de un antiguo esplendor, ahora devastado y vencido por el paso del tiempo. La refacción de la casona constituye una empresa utópica que, aunque condenada al fracaso, trasciende el plano arquitectónico y alcanza alturas revolucionarias, políticas, en el delirio narrativo. La entronización del Corazón de Jesús cuando la casa es inaugurada se erige como la posibilidad de reunir a las presencias amadas en una fiesta heterotópica y soñar con ganarle la batalla no solo a Colombia, la mala patria, sino fundamentalmente a la destrucción y a la muerte. Así, la escritura deviene funeraria, poblada de los vestigios y de la irreductible presencia de los otros, los muertos y los animales, quienes encuentran un espacio hospitalario en el recuerdo y la memoria. Palabras clave: Fernando Vallejo, Casablanca la bella, devastación, muerte, animales, heterotopía, memoria. Abstract Casablanca la bella (2013), the latest novel by Fernando Vallejo, is a continuation of the dialogue the writer has with Death in earlier works. The novel shows and displays the writer‘s obsession from the moment he buys Casablanca, an old house in the Laureles neighbourhood, Medellin, and begins its restoration. -

“Conmigo Ella No Quiere Bailar” Los Estereotipos

Facultad de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales Grado en Relaciones Internacionales Trabajo Fin de Grado “Conmigo ella no quiere bailar” Los Estereotipos de Género y su Reflejo en las Letras de las Canciones de Reggaetón Estudiante: Isabel García de Paredes Sánchez Directora: Prof. Isabel Maravall Buckwalter Madrid, mayo de 2020 1 ÍNDICE I. INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................... ¡Error! Marcador no definido. 1. Finalidad y motivos ........................................................................................ 4 2. Estado de la cuestión y marco teórico ........................................................... 5 3. Objetivos del trabajo ...................................................................................... 5 4. Metodología del trabajo ................................................................................. 6 5. Estructura del trabajo .................................................................................... 6 II. EL ARTÍCULO 5 DE LA CONVENCIÓN CONTRA LA DISCIMINACIÓN DE LA MUJER .............................................................................. 6 1. Un análisis de los estereotipos de género ...................................................... 7 2. Obligaciones de los Estados respecto a los estereotipos de género .............. 9 III. ANÁLISIS DE DOS ESTEREOTIPOS: LA MASCULINIDAD TÓXICA Y EL CONSENTIMIENTO ........................................................................ 11 1. Los estereotipos de lo “masculino”: un constructo tóxico .......................... 12 -

Carcajadas Desde Lo Bizarro

CARCAJADAS DESDE LO BIZARRO: Las contrafactas como herramienta feminista de resignificación, subversión y empoderamiento. María del Carmen Romero Alcalá Trabajo fin de máster para optar al título de Máster Erasmus Mundus en Estudios de las Mujeres y de Género Directora Principal: Ana Gallego Cuiñas, Universidad de Granada. Directora de apoyo: Suzanne M Clisby, University of Hull. Granada, septiembre de 2015 CARCAJADAS DESDE LO BIZARRO: Las contrafactas como herramienta feminista de resignificación, subversión y empoderamiento. María del Carmen Romero Alcalá Directora Principal: Ana Gallego Cuiñas, Universidad de Granada. Directora de apoyo: Suzanne M Clisby, University of Hull. Granada, septiembre de 2015 Firma de aprobación: 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Gracias primero a lxs primerxs: mi familia. Si no fuera por los privilegios que ellxs me han dado, no estaría aquí. Por desgracia en este país ni siquiera cuando el estado considera que sí necesitas una beca, te la da a tiempo. Si no fuera por ellxs, aparte de no existir, y de no ser en gran medida quien soy, no podría jamás haber vivido la experiencia de este máster. A mi tutora, Ana Gallego, por su dedicación, y apoyo, así como a todas las profesoras del máster que me han ayudado a orientarme en todo mi limbo inicial. A Víctor y Miriam, por ayudarme con sus conversaciones en este trabajo, por dejarme basarme en ellxs, por su amabilidad e interés. A mis compañeras Marcelinas que me han apoyado tanto, con las que me he sentido y me siento tan querida, tan apoyada, y tan libre de ser quien soy. De quien más he aprendido en este viaje ha sido de vosotrxs y con vosotrxs. -

Estudio Del Metalenguaje En Las Letras De Javier Ibarra Ramos. Study of Metalanguage in the Lyrics of Javier Ibarra Ramos

Trabajo Fin de Grado Estudio del metalenguaje en las letras de Javier Ibarra Ramos. Study of metalanguage in the lyrics of Javier Ibarra Ramos. Autor Belén Subías Peirón Director José Ángel Blesa Lalinde Facultad de Filosofía y Letras 2019/2020 1 Resumen: En el presente trabajo se realiza un estudio del metalenguaje en las letras del cantante Javier Ibarra Ramos, mediante una clasificación de las diferentes partes que engloban el metalenguaje. para ello me he basado principalmente en los estudios de Jakobson de su ensayo “Lingüística y poética” (Jakobson, 1975) y de Coseriu (Coseriu, 1990), tomando como referencia la clasificación que realiza de los tres niveles fundamentales del lenguaje en nivel universal, nivel histórico y nivel individual. Para las clasificaciones pertinentes en los tres niveles del lenguaje he seguido los estudios de Óscar Loureda Lamas (Loureda Lamas, 2009), así como los que realiza juntamente con Ramón González Ruiz (González Ruiz y Loureda Lamas, 2005). Palabras clave: metalenguaje, Jakobson, Coseriu, nivel universal, nivel histórico, nivel individual. Abstract: In the present work, a study of the metalanguage in the lyrics of the singer Javier Ibarra Ramos is carried out, through a classification of the different parts that encompass the metalanguage. For this, I have mainly based on Jakobson's studies of his essay "Linguistics and Poetics" and on Coseriu, taking as a reference the classification he makes of the three fundamental levels of language at the universal, historical and individual levels. For the pertinent classifications in the three levels of language, I have followed the studies of Óscar Loureda Lamas, as well as those carried out together with Ramón González Ruiz. -

1. La Maraña ¿? 1 Ext./Int. Creditos; Aereo Ciudad; Casa

1. LA MARAÑA ¿? 1 EXT./INT. CREDITOS; AEREO CIUDAD; CASA JUANJO - NOCHE NAVIDAD. Aparecen los CRÉDITOS sobre las luces de la ciudad. Los edificios más altos parecen muy cercanos. Vamos buscando la cristalera de uno de esos edificios de lujo, en una de las plantas más altas, a través de los cristales, descubrimos a JUANJO (45), envuelto en una toalla de baño, su atlético torso desnudo. Estamos en el VESTIDOR, todo respira orden y mucha pulcritud. Con el efecto necesario nos colamos en el interior. La cámara nos muestra el interior de los armarios abiertos, todos los trajes siguen un patrón según color, igual ocurre con pantalones, jerséis, zapatos… De fondo se deja sentir una melodía alegre de Mozart. Por fin descubrimos un “smoking” colgado de un “buenas noches” (o perchero de pie). El barrido del smoking nos lleva a: ENCADENADO A: 2 INT. CASA JUANJO; VESTIDOR - NOCHE Siguen los CRÉDITOS Imagen viene de sec. anterior. De fondo se deja oír a Mozart. Las puertas de todos los armarios se van cerrando dejando que la imagen de JUANJO se refleje en todos los espejos. Terminan los CRÉDITOS. Mozart se funde con la música de una orquesta de la sec. siguiente, algo festivo. Se apaga la luz: FUNDE A NEGRO 2. 3 INT. MANSIÓN LUJO - NOCHE La imagen y el sonido vienen de sec. anterior. Sobre la orquesta, un letrero: FELIZ AÑO (¿?) y el logo de la cadena (a crear). La sala se llena de barullo y de gentes vestidas para la ocasión. Dos matrimonios charlan animadamente. Pasan la cincuentena de años. -

Análisis Semiótico De Calle 13: Hacia Una Identidad Latinoamericana

Universidad de San Andrés Departamento de Ciencias Sociales Trabajo de Licenciatura en Comunicación “Soy América Latina, un pueblo sin piernas, pero que camina” Análisis semiótico de Calle 13: Hacia una identidad latinoamericana Autor: Manuel Freixas 20096 Mentor: Gastón Cingolani Victoria, 2014 A Eliseo Verón, de quien no sólo tomé prestada una teoría, sino una forma de entender la comunicación, QEPD “Y es que, por la virginidad del paisaje, por la formación, por la ontología, por la presencia fáustica del indio y del negro, por la Revolución que constituyó su reciente descubrimiento, por los fecundos mestizajes que propició, América está muy lejos de haber agotado su caudal de mitologías.” Alejo Carpentier, El Reino de este Mundo 2 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................. 4 ¿Por qué Calle 13? ........................................................................................................................ 5 MARCO TEÓRICO ............................................................................... 9 Teoría de los Discursos Sociales ............................................................................................ 9 Hipótesis ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Estrategia metodológica.......................................................................................................... 12 Estructura .................................................................................................................................... -

La Mediadora.Indd

A n PREMIO ABOGADOS DE nOVELA Sólo aceptando nuestra realidad, 2015 podremos cambiar nuestro destino LA A n Es muy probable que la historia que se cuenta en esta novela, la de Mavi PREMIO y Agustín, nos toque muy de cerca. Su divorcio engrosa esa estadística que MEDIADORA ABOGADOS sitúa a España como el quinto país del mundo por número de rupturas DE nOVELA matrimoniales. 2015 JESÚS SÁNCHEZ ADALID (Villanueva de El relato del desamor de esta pareja nos resultará tan familiar que incluso la Serena, Badajoz, 1962) se licenció en Derecho en algún momento nos parecerá haberlo vivido personalmente: es la vida El Consejo General de la Abogacía por la Universidad de Extremadura y realizó Española, la Mutualidad de la los cursos de doctorado en la Universidad misma, con su carga de incertidumbre, desconcierto y hasta fracaso. Pero Abogacía y Ediciones Martínez Roca Complutense de Madrid. Ejerció de juez durante también el misterioso juego de las oportunidades; la esperanza en que dos años, tras los cuales estudió Filosofía algunos desastres no tienen por que acabar necesariamente mal. (Grupo Planeta) han convocado la LA MEDIADORA y Teología. Además se licenció en Derecho sexta edición del Premio Abogados de Canónico por la Universidad Pontifi cia de Esta es la historia de toda una generación que tal vez no estaba preparada Novela, con la intención de premiar Salamanca. Es profesor de ética en el Centro del todo para los grandes cambios que iban a afectar a sus relaciones, a sus una novela que ayude al lector a Universitario Santa Ana de Almendralejo. -

Diario De Sesiones Del Congreso De Los Diputados

CORTES GENERALES DIARIO DE SESIONES DEL CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS PLENO Y DIPUTACIÓN PERMANENTE Año 2020 XIV LEGISLATURA Núm. 56 Pág. 1 PRESIDENCIA DE LA EXCMA. SRA. D.ª MERITXELL BATET LAMAÑA Sesión plenaria núm. 53 celebrada el jueves 22 de octubre de 2020 Página ORDEN DEL DÍA: Moción de censura. (Continuación): — Moción de censura al Gobierno presidido por don Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón, que incluye como candidato a la Presidencia del Gobierno a don Santiago Abascal Conde. «BOCG. Congreso de los Diputados», serie D, número 156, de 8 de octubre de 2020. (Número de expediente 82/000001) ................................................................................... 3 cve: DSCD-14-PL-56 DIARIO DE SESIONES DEL CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS PLENO Y DIPUTACIÓN PERMANENTE Núm. 56 22 de octubre de 2020 Pág. 2 SUMARIO Se reanuda la sesión a las nueve de la mañana. Página Moción de censura. (Continuación) ........................................................................................ 3 Página Moción de censura al Gobierno presidido por don Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón, que incluye como candidato a la Presidencia del Gobierno a don Santiago Abascal Conde .......... 3 Intervienen las señoras Muñoz Dalda, Fernández Castañón, Vidal Sáez y Maestro Moliner, del Grupo Parlamentario Confederal de Unidas Podemos-En Comú Podem-Galicia en Común. Contesta el señor candidato propuesto en la moción de censura, Abascal Conde. Replica la señora Fernández Castañón y duplica el señor candidato propuesto en la moción de censura, Abascal Conde. La Presidencia informa de que la votación presencial no tendrá lugar antes de las trece horas. Asimismo anuncia que la finalización del plazo para la emisión del voto telemático será a las doce de la mañana.