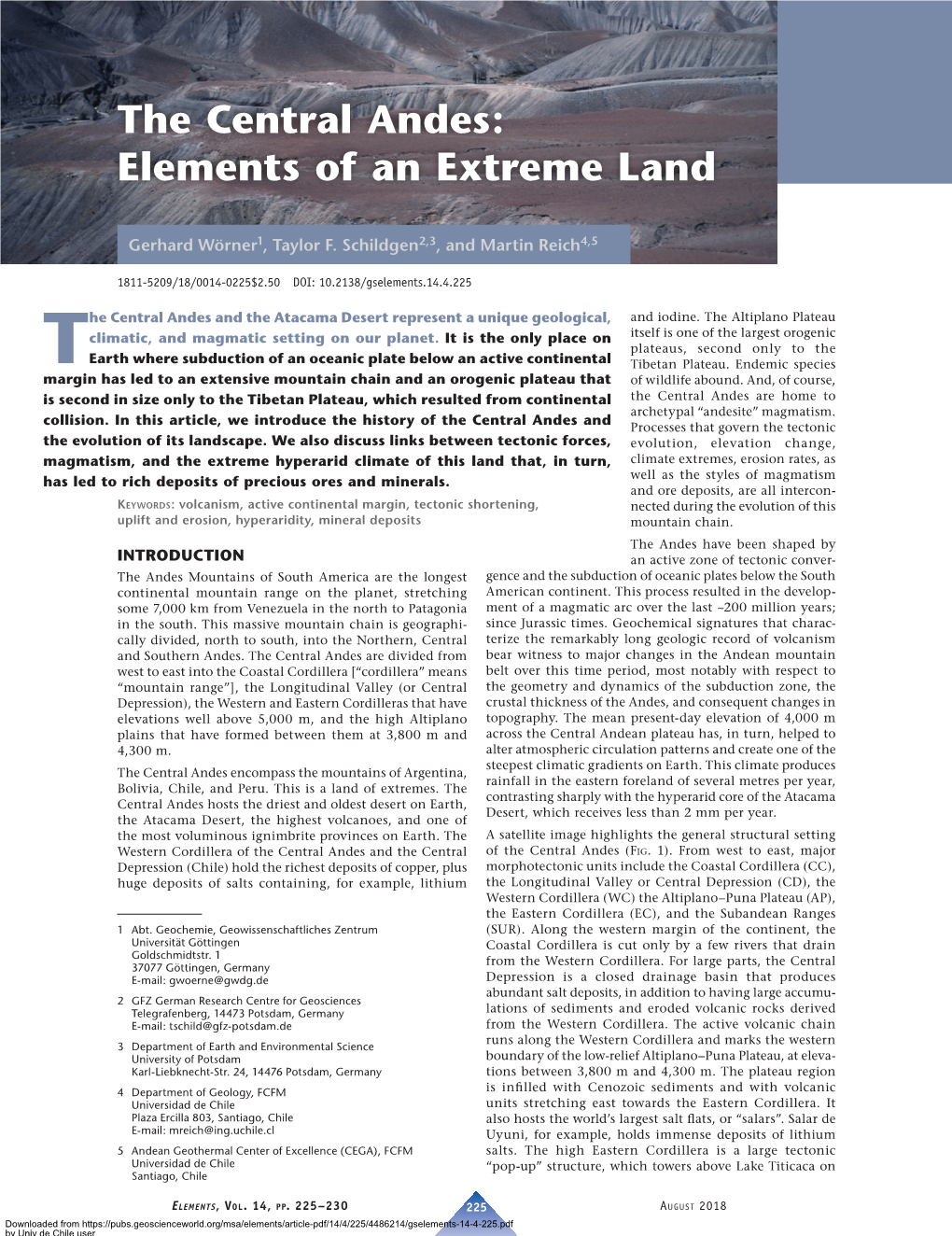

The Central Andes: Elements of an Extreme Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caking Caliche (Lime-Pan)

C CAKING CAPILLARITY Changing of a powder into a solid mass by heat, pressure, The tendency of a liquid to enter into the narrow pores or water. within a porous body, due to the combination of the cohe- sive forces within the liquid (expressed in its surface ten- sion) and the adhesive forces between the liquid and the solid (expressed in their contact angle). CALICHE (LIME-PAN) Bibliography Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics. (First Edition). 2003. (I)A zone near the surface, more or less cemented by sec- Elsevier Inc. Daniel Hillel (ed.) http://www.sciencedirect.com/ ondary carbonates of Ca or Mg precipitated from the soil science/book/9780123486554 solution. It may occur as a soft thin soil horizon, as a hard thick bad, or as a surface layer exposed by erosion. Cross-references (II) Alluvium cemented with NaNO3, NaCl and/or other Sorptivity of Soils soluble salts in the nitrate deposits of Chile and Peru. Bibliography CAPILLARY FRINGE Glossary of Soil Science Terms. Soil Science Society of America. 2010. https://www.soils.org/publications/soils-glossary The thin zone just above the water table that is still satu- rated, though under sub-atmospheric pressure (tension). The thickness of this zone (typically a few centimeters or CANOPY STRUCTURE decimeters) represents the suction of air entry for the par- ticular soil. Plant canopy structure is the spatial arrangement of the above-ground organs of plants in a plant community. Bibliography Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics. (First Edition). 2003. Elsevier Inc. Daniel Hillel (ed.) http://www.sciencedirect.com/ Bibliography science/book/9780123486554 Russel, G., Marshall, B., and Gordon Jarvis, P. -

And Gas-Based Geochemical Prospecting Of

Water- and gas-based geochemical prospecting of geothermal reservoirs in the Tarapacà and Antofagasta regions of northern Chile Tassi, F.1, Aguilera, F.2, Vaselli, O.1,3, Medina, E.2, Tedesco, D.4,5, Delgado Huertas, A.6, Poreda, R.7 1) Department of Earth Sciences, University of Florence, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121, Florence, Italy 2) Departamento de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad Católica del Norte, Av. Angamos 0610, 1280, Antofagasta, Chile 3) CNR-IGG Institute of Geosciences and Earth Resources, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121, Florence, Italy 4)Department of Environmental Sciences, 2nd University of Naples, Via Vivaldi 43, 81100 Caserta, Italy 5) CNR-IGAG National Research Council, Institute of Environmental Geology and Geo-Engineering, Pzz.e A. Moro, 00100 Roma, Italy. 6) CSIS Estacion Experimental de Zaidin, Prof. Albareda 1, 18008, Granada, Spain. 7) Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, 227 Hutchinson Hall, Rochester, NY 14627, U.S.A.. Studied area The Andean Central Volcanic Zone, which runs parallel the Central Andean Cordillera crossing from North to This study is mainly focused on the geochemical characteristics of water and gas South the Tarapacà and Antofagasta regions of northern Chile, consists of several volcanoes that have shown phases of thermal fluids discharging in several geothermal areas of northern Chile historical and present activity (e.g. Tacora, Guallatiri, Isluga, Ollague, Putana, Lascar, Lastarria). Such an intense (Fig. 1); volcanism is produced by the subduction process thrusting the oceanic Nazca Plate beneath the South America Plate. The anomalous geothermal gradient related to the geodynamic assessment of this extended area gives El Tatio, Apacheta, Surire, Puchuldiza-Tuya also rise to intense geothermal activity not necessarily associated with the volcanic structures. -

1.CEINTURE DE FEU, Paris

Cette ligne est matérialisée par une rainure dans la façade, dans laquelle sera logée une ligne de néons rouge/orangé, couleurd’origine dugaznéon. danslafaçade, danslaquelleseralogéeunelignedenéonsrouge/orangé, Cette ligneestmatérialisée parunerainure estla plus intense que l’activitéterrestre Ce qui projet, se déploie sur les 4 façades du bâtiment central de est la de la Ceinture Feu, représentation ligne qui par imaginaire relie, 352 points, tous les volcans le émergés long de la plaque Pacifique. C’est dans cette zone ontdatél’originedusystèmesolaire. del’IPGPqui,lespremiers, etàsonétudescientifique.Cesontleschercheurs àlaTerre dePhysiqueduGlobe,rueCuvieràParis,estundes10lieuxaumondeconsacrés L’Institut Vinson Murphy Takahe Toney Frakes Steere Siple Hampton Sidley Waesche Andrus Moulton Berlin Morning Discovery Terror Erebus - · · Melbourne autre. Overlord DE FEU. JUIN 2009 Burney Lautaro Hudson Macá AGENCE PIECES MONTEES Melimoyu Corcovado ANGELA DETANICO, RAFAEL LAIN Minchinmávida Tronador INSTITUT DE PHYSIQUE DU GLOBE, PARIS Osorno Nouvelle-Zélande dans le Pacifique Sud. LA CEINTURE DE FEU Puntiagudo Cette zone est également caractérisée par de l’Amérique Centrale et des zones côtières de Un très grand nombre des volcans mondiaux est plus de la moitié des volcans en activité au- Cette intense activité volcanique et sismique Lanín actifs sont situés dans la ceinture de feu, et d’enfoncement d’une plaque tectonique sous une l’Australie pour englober les îles Fidji et la La CEINTURE DE FEU est une ligne imaginaire qui Elle suit en grande partie la plaque pacifique. rassemblé sur cette ligne de 40 000 km de long. Parmi les 1500 volcans sur la planète, les plus dessus du niveau de la mer forme cette CEINTURE correspond à des zones de subduction, processus Cette longue guirlande d’îles volcaniques prend naissance à la pointe méridionale de l’Amérique relie les 452 volcans qui bordent l’Océan Pacifique. -

Magmatic Evolution of the Nevado Del Ruiz Volcano, Central Cordillera, Colombia Minera1 Chemistry and Geochemistry

Magmatic evolution of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano, Central Cordillera, Colombia Minera1 chemistry and geochemistry N. VATIN-PÉRIGNON “‘, P. GOEMANS “‘, R.A. OLIVER ‘*’ L. BRIQUEU 13),J.C. THOURET 14J,R. SALINAS E. 151,A. MURCIA L. ” Abstract : The Nevado del RU~‘, located 120 km west of Bogota. is one of the currently active andesitic volcanoes that lies north of the Central Cordillera of Colombia at the intersection of two dominant fault systems originating in the Palaeozoïc basement. The pre-volcanic basement is formed by Palaeozoïc gneisses intruded by pre-Cretaceous and Tertiarygranitic batholiths. They are covered by lavas and volcaniclastic rocks from an eroded volcanic chain dissected during the late Pliocene. The geologic history of the Nevado del Ruiz records two periods of building of the compound volcano. The stratigraphie relations and the K-Ar dating indicate that effusive and explosive volcanism began approximately 1 Ma ago with eruption of differentiated andesitic lava andpyroclastic flows and andesitic domes along a regional structural trend. Cataclysmic eruptions opened the second phase of activity. The Upper sequences consist of block-lavas and lava domes ranging from two pyroxene-andesites to rhyodacites. Holocene to recent volcanic eruptions, controled by the intense tectonic activity at the intersection of the Palestina fawlt with the regional fault system, are similar in eruptive style and magma composition to eruptions of the earlier stages of building of the volcano. The youngest volcanic activity is marked by lateral phreatomagmatic eruptions, voluminous debris avalanches. ash flow tuffs and pumice falls related to catastrophic collapse during the historic eruptions including the disastrous eruption of 1985. -

Appendix A. Supplementary Material to the Manuscript

Appendix A. Supplementary material to the manuscript: The role of crustal and eruptive processes versus source variations in controlling the oxidation state of iron in Central Andean magmas 1. Continental crust beneath the CVZ Country Rock The basement beneath the sampled portion of the CVZ belongs to the Paleozoic Arequipa- Antofalla terrain – a high temperature metamorphic terrain with abundant granitoid intrusions that formed in response to Paleozoic subduction (Lucassen et al., 2000; Ramos et al., 1986). In Northern Chile and Northwestern Argentina this Paleozoic metamorphic-magmatic basement is largely homogeneous and felsic in composition, consistent with the thick, weak, and felsic properties of the crust beneath the CVZ (Beck et al., 1996; Fig. A.1). Neodymium model ages of exposed Paleozoic metamorphic-magmatic basement and sediments suggest a uniform Proterozoic protolith, itself derived from intrusions and sedimentary rock (Lucassen et al., 2001). AFC Model Parameters Pervasive assimilation of continental crust in the Central Andean ignimbrite magmas is well established (Hildreth and Moorbath, 1988; Klerkx et al., 1977; Fig. A.1) and has been verified by detailed analysis of radiogenic isotopes (e.g. 87Sr/86Sr and 143Nd/144Nd) on specific systems within the CVZ (Kay et al., 2011; Lindsay et al., 2001; Schmitt et al., 2001; Soler et al., 2007). Isotopic results indicate that the CVZ magmas are the result of mixing between a crustal endmember, mainly gneisses and plutonics that have a characteristic crustal signature of high 87Sr/86Sr and low 145Nd/144Nd, and the asthenospheric mantle (low 87Sr/86Sr and high 145Nd/144Nd; Fig. 2). In Figure 2, we model the amount of crustal assimilation required to produce the CVZ magmas that are targeted in this study. -

Evaluación Del Riesgo Volcánico En El Sur Del Perú

EVALUACIÓN DEL RIESGO VOLCÁNICO EN EL SUR DEL PERÚ, SITUACIÓN DE LA VIGILANCIA ACTUAL Y REQUERIMIENTOS DE MONITOREO EN EL FUTURO. Informe Técnico: Observatorio Vulcanológico del Sur (OVS)- INSTITUTO GEOFÍSICO DEL PERÚ Observatorio Vulcanológico del Ingemmet (OVI) – INGEMMET Observatorio Geofísico de la Univ. Nacional San Agustín (IG-UNSA) AUTORES: Orlando Macedo, Edu Taipe, José Del Carpio, Javier Ticona, Domingo Ramos, Nino Puma, Víctor Aguilar, Roger Machacca, José Torres, Kevin Cueva, John Cruz, Ivonne Lazarte, Riky Centeno, Rafael Miranda, Yovana Álvarez, Pablo Masias, Javier Vilca, Fredy Apaza, Rolando Chijcheapaza, Javier Calderón, Jesús Cáceres, Jesica Vela. Fecha : Mayo de 2016 Arequipa – Perú Contenido Introducción ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Objetivos ............................................................................................................................................ 3 CAPITULO I ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Volcanes Activos en el Sur del Perú ........................................................................................ 4 1.1 Volcán Sabancaya ............................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Misti .................................................................................................................................. -

Final Copy 2021 03 23 Ituarte

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Ituarte, Lia S Title: Exploring differential erosion patterns using volcanic edifices as a proxy in South America General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Exploring differential erosion patterns using volcanic edifices as a proxy in South America Lia S. Ituarte A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Master by Research in the Faculty of Science, School of Earth Sciences, October 2020. -

Sedimentology of Caliche (Calcrete) Occurrences of the Kirşehir Region

Mineral Res. Expl. Bull., 120, 69-80, 1998 SEDIMENTOLOGY OF CALICHE (CALCRETE) OCCURRENCES OF THE KIRŞEHİR REGION Eşref ATABEY*; Nevbahar ATABEY* and Haydar KARA* ABSTRACT.- Study was conducted in the Kırşehir region. Carbonate occurrences within the upper Miocene-Pliocene deposits forming the subsidence basins surrounded by the Kırşehir massive, are described as caliche. These caliche deposits in the alluvial fan-meandering river and lacustrine environments are found in three different zones. In the measured, sections, conglomerate comprises the basement and is overlain by a transition zone made of sandy mudstone (Zone I). Above them is the rarely nodular carbonaceous zone with horizontal and vertical positions in the reddish mudstone-siltstone (Zone II). Finally, laminated caliche (calcrite) comprises the upper most part (Zone III). Carbonates in the basement, country rocks, and in the soil are dissolved in the acidic environment and become a solution saturated with calcium bicarbonate. This solution is transported to the sediments and capillary rises through the sediments during arid-semi arid seasons. Carbondioxide in the Ca and HCO3- bearing solution is removed from the system and as a result, calcium carbonate nodules and laminated caliche are formed. These stromatolite-like laminated caliche occurrences show a criptoalgal structure under polarized microscope and scanning electron microscope (SEM), and they contain microerosional surfaces and caliche pisolites that are formed by dissolution. Caliche occurrences are believed to be source of camotite, thorium, vanadium, sepiolite, huntite, dolomite, and magnesite. INTRODUCTION sand, silt, and soil under semi-arid and arid climate re- gimes. The term of caliche is used as a synonymous of Study area comprises around of the city of Kırşehir calcrete and also known as calcrete crust and limesto- in the Central Anatolia (Fig. -

Effects of Volcanism, Crustal Thickness, and Large Scale Faulting on the He Isotope Signatures of Geothermal Systems in Chile

PROCEEDINGS, Thirty-Eighth Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering Stanford University, Stanford, California, February 11-13, 2013 SGP-TR-198 EFFECTS OF VOLCANISM, CRUSTAL THICKNESS, AND LARGE SCALE FAULTING ON THE HE ISOTOPE SIGNATURES OF GEOTHERMAL SYSTEMS IN CHILE Patrick F. DOBSON1, B. Mack KENNEDY1, Martin REICH2, Pablo SANCHEZ2, and Diego MORATA2 1Earth Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720 USA 2Departamento de Geología y Centro de Excelencia en Geotermia de los Andes, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, CHILE [email protected] agree with previously published results for the ABSTRACT Chilean Andes. The Chilean cordillera provides a unique geologic INTRODUCTION setting to evaluate the influence of volcanism, crustal thickness, and large scale faulting on fluid Measurement of 3He/4He in geothermal water and gas geochemistry in geothermal systems. In the Central samples has been used to guide geothermal Volcanic Zone (CVZ) of the Andes in the northern exploration efforts (e.g., Torgersen and Jenkins, part of Chile, the continental crust is quite thick (50- 1982; Welhan et al., 1988) Elevated 3He/4He ratios 70 km) and old (Mesozoic to Paleozoic), whereas the (R/Ra values greater than ~0.1) have been interpreted Southern Volcanic Zone (SVZ) in central Chile has to indicate a mantle influence on the He isotopic thinner (60-40 km) and younger (Cenozoic to composition, and may indicate that igneous intrusions Mesozoic) crust. In the SVZ, the Liquiñe-Ofqui Fault provide the primary heat source for the associated System, a major intra-arc transpressional dextral geothermal fluids. Studies of helium isotope strike-slip fault system which controls the magmatic compositions of geothermal fluids collected from activity from 38°S to 47°S, provides the opportunity wells, hot springs and fumaroles within the Basin and to evaluate the effects of regional faulting on Range province of the western US (Kennedy and van geothermal fluid chemistry. -

Sr–Pb Isotopes Signature of Lascar Volcano (Chile): Insight Into Contamination of Arc Magmas Ascending Through a Thick Continental Crust N

Sr–Pb isotopes signature of Lascar volcano (Chile): Insight into contamination of arc magmas ascending through a thick continental crust N. Sainlot, I. Vlastélic, F. Nauret, S. Moune, F. Aguilera To cite this version: N. Sainlot, I. Vlastélic, F. Nauret, S. Moune, F. Aguilera. Sr–Pb isotopes signature of Lascar volcano (Chile): Insight into contamination of arc magmas ascending through a thick continental crust. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, Elsevier, 2020, 101, pp.102599. 10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102599. hal-03004128 HAL Id: hal-03004128 https://hal.uca.fr/hal-03004128 Submitted on 13 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Manuscript File Sr-Pb isotopes signature of Lascar volcano (Chile): Insight into contamination of arc magmas ascending through a thick continental crust 1N. Sainlot, 1I. Vlastélic, 1F. Nauret, 1,2 S. Moune, 3,4,5 F. Aguilera 1 Université Clermont Auvergne, CNRS, IRD, OPGC, Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, F-63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France 2 Observatoire volcanologique et sismologique de la Guadeloupe, Institut de Physique du Globe, Sorbonne Paris-Cité, CNRS UMR 7154, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France 3 Núcleo de Investigación en Riesgo Volcánico - Ckelar Volcanes, Universidad Católica del Norte, Avenida Angamos 0610, Antofagasta, Chile 4 Departamento de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad Católica del Norte, Avenida Angamos 0610, Antofagasta, Chile 5 Centro de Investigación para la Gestión Integrada del Riesgo de Desastres (CIGIDEN), Av. -

Fertilizing Home Gardens in Arizona Tom Degomez

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1020 February, 2009 Fertilizing Home Gardens in Arizona Tom DeGomez Gardens provide excellent quality vegetables for fresh Examples: 15-10-5 fertilizer contains 15% nitrogen, 10% use and for processing if the crops are supplied with an phosphate and 5% potash: 21-0-0 fertilizer contains 21% adequate level of nutrients and water. Other important nitrogen, but no phosphate or potash. management practices include plant spacing, insect, weed, and disease control, and timely harvest. This fertilizer guide Application Methods for vegetable gardens aims at ensuring ample levels of all nutrients for optimum yield and quality. There are different methods of applying fertilizer depending on its formulation and the crop needs. Differing opinions have been expressed for many years concerning the merits of fertilizing with manures or other The following terms describe the way fertilizer may be organic fertilizers versus “chemical” fertilizers. Excellent applied to a garden area. gardens can be grown using either method. Soil bacteria and fungi must act on the organic nutrient sources to change Broadcast: The material is scattered uniformly over the them into forms that plants can use. A major consideration surface of the soil before the garden is planted. Nutrients in the use of organic sources is applying materials far are more readily available to plant roots if fertilizers are enough in advance to allow for breakdown of the substance worked into the upper 3” to 4” of the soil. to ensure that an adequate supply of nutrients will be available when the growing plant needs it. Plants do not Band: Fertilizer is placed in a trench about 2-3” deep. -

Long Term Atmospheric Deposition As the Source of Nitrate and Other Salts in the Atacama Desert, Chile

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Vol. 68, No. 20, pp. 4023-4038, 2004 Copyright © 2004 Elsevier Ltd Pergamon Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0016-7037/04 $30.00 ϩ .00 doi:10.1016/j.gca.2004.04.009 Long term atmospheric deposition as the source of nitrate and other salts in the Atacama Desert, Chile: New evidence from mass-independent oxygen isotopic compositions 1, 2 1 GREG MICHALSKI, *J.K.BÖHLKE and MARK THIEMENS 1Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0356, USA 2United States Geological Survey, 431 National Center, Reston, VA 20192, USA (Received August 19, 2003; accepted in revised form April 7, 2004) Abstract—Isotopic analysis of nitrate and sulfate minerals from the nitrate ore fields of the Atacama Desert in northern Chile has shown anomalous 17O enrichments in both minerals. ⌬17O values of 14–21 ‰ in nitrate and0.4to4‰insulfate are the most positive found in terrestrial minerals to date. Modeling of atmospheric processes indicates that the ⌬17O signatures are the result of photochemical reactions in the troposphere and stratosphere. We conclude that the bulk of the nitrate, sulfate and other soluble salts in some parts of the Atacama Desert must be the result of atmospheric deposition of particles produced by gas to particle conversion, with minor but varying amounts from sea spray and local terrestrial sources. Flux calculations indicate that the major salt deposits could have accumulated from atmospheric deposition in a period of 200,000 to 2.0 M years during hyper-arid conditions similar to those currently found in the Atacama Desert.