Idlib Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education in Danger

Education in Danger Monthly News Brief December Attacks on education 2019 The section aligns with the definition of attacks on education used by the Global Coalition to Protect Education under Attack (GCPEA) in Education under Attack 2018. Africa This monthly digest compiles reported incidents of Burkina Faso threatened or actual violence 10 December 2019: In Bonou village, Sourou province, suspected affecting education. Katiba Macina (JNIM) militants allegedly attacked a lower secondary school, assaulted a guard and ransacked the office of the college It is prepared by Insecurity director. Source: AIB and Infowakat Insight from information available in open sources. 11 December 2019: Tangaye village, Yatenga province, unidentified The listed reports have not been gunmen allegedly entered an unnamed high school and destroyed independently verified and do equipment. The local town hall was also destroyed in the attack. Source: not represent the totality of Infowakat events that affected the provision of education over the Cameroon reporting period. 08 December 2019: In Bamenda city, Mezam department, Nord-Ouest region, unidentified armed actors allegedly abducted around ten Access data from the Education students while en route to their campus. On 10 December, the in Danger Monthly News Brief on HDX Insecurity Insight. perpetrators released a video stating the students would be freed but that it was a final warning to those who continue to attend school. Visit our website to download Source: 237actu and Journal Du Cameroun previous Monthly News Briefs. Mali Join our mailing list to receive 05 December 2019: Near Ansongo town, Gao region, unidentified all the latest news and resources gunmen reportedly the director of the teaching academy in Gao was from Insecurity Insight. -

II. Cross Shelling Between Syrian Regular Forces and Armed Opposition Groups

22 Dead, 65 Others Injured, in Syrian Regular Forces’ Shelling of Regions in Hama and Idlib www.stj-sy.com 22 Dead, 65 Others Injured, in Syrian Regular Forces’ Shelling of Regions in Hama and Idlib The shelling incidents took place in January 2019, in a violation of the de-escalation deal. In return, armed opposition groups bombarded several posts held by the Syrian government Page | 2 22 Dead, 65 Others Injured, in Syrian Regular Forces’ Shelling of Regions in Hama and Idlib www.stj-sy.com In southern rural Idlib and northern rural Hama1, several regions witnessed a rising tempo of the Syrian regular forces and their Russian ally’s shelling in January 2019, for the regions have endured almost daily shelling that on numerous cases targeted civilian areas, leading to the death of no less than 22 persons, women and children included, and the injury of about 65 others. The shelling that targeted the city of Maarrat al-Nu'man, Idlib, is, however, considered the most violent, where the toll rose to 11 dead civilians and 35 injured others. On the other side, armed opposition groups bombarded several Syrian regular forces-held posts in Hama, responding to the latter’s violation of the de-escalation deal, according to testimonies obtained by Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ. I. Shelling of Southern Rural Idlib: STJ’s field researchers monitored attacks on no less than 16 towns and cities, which have been targeted with artillery, missile and aerial shelling by the Syrian regular forces and the Russian forces in January 2019. -

Seven Years of Crisis Islamic Relief’S Humanitarian Response in Syria 2012-2017

SEVEN YEARS OF CRISIS ISLAMIC RELIEF’S HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IN SYRIA 2012-2017 1 ISLAMIC RELIEF USA Islamic Relief USA has been serving humanity for the past 25 years. With an active presence in over 30 countries across the globe, we strive to work together for a better world for the three billion people still living in poverty. Since we received our first donation in 1993, we Our Values have helped millions of the world’s poorest and We remain guided by the timeless values and most vulnerable people. Inspired by the Islamic teachings of the Qur’an and the prophetic faith and guided by our values, we believe that example (Sunnah), most specifically: we have a duty to help those less fortunate – regardless of race, political affiliation, gender, or Sincerity (Ikhlas) belief. In responding to poverty and suffering, our efforts Our projects provide vulnerable people with are driven by sincerity to God and the need to fulfil access to vital services. We protect communities our obligations to humanity. from disasters and deliver life-saving emergency aid. We provide lasting routes out of poverty, and Excellence (Ihsan) empower vulnerable people to transform their lives and their communities. Our actions in tackling poverty are marked by excellence in our operations and the conduct Our Mission through which we help the people we serve. Islamic Relief USA provides relief and Compassion (Rahma) development in a dignified manner regardless of We believe the protection and well-being of every gender, race, or religion, and works to empower life is of paramount importance and we shall join individuals in their communities and give them a with other humanitarian actors to act as one in voice in the world. -

Security Council Distr.: General 9 October 2012

United Nations S/2012/651 Security Council Distr.: General 9 October 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 16 August 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25, 27 and 28 June, 2, 3, 9, 11, 13, 17 and 24 July, and 1, 2, 8, 10 and 14 to 16 August 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria from Thursday evening, 9 August 2012, until Friday evening, 10 August 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-54062 (E) 221012 231012 *1254062* S/2012/651 Annex to the identical letters dated 16 August 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] List of acts of aggression and violations committed by armed terrorist groups from 2000 hours on 9 August 2012 to 2000 hours on 10 August 2012 No. Place Time Violations committed by armed terrorist groups and outcomes 1 Syrian-Lebanese border 2355 There was an attempted infiltration from Lebanese territory into Syrian territory, and border guards in the vicinity of the Kabir al-Janubi River came under fire. -

In Kafr Nabl in Idlib Province on 26 September 2017

About Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ Syrians for Truth and Justice /STJ is a nonprofit, nongovernmental, independent Syrian organization. STJ includes many defenders and human rights defenders from Syria and from different backgrounds and affiliations, including academics of other nationalities. The organization works for Syria, where all Syrians, without discrimination, should be accorded dignity, justice and equal human rights. 1 Table of Content About Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ ....................................................................................................... 1 Background: .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ 5 First: Attack on Medical Facility in Madyara on September 11, 2017 ......................................................... 6 Second: Attack on al-Hekma Hospital in Kafr Batna in on September 13, 2017 ......................................... 9 Third: Attack on Kafr Nabl Surgical Hospital in Kafr Nabl City on September 19, 2017 ............................ 11 Fourth: Targeting the Al-Rahma Cave Hospital in Khan Sheikhoun City on 19 and 20 September 2017 .. 21 Fifth: News -

“Targeting Life in Idlib”

HUMAN RIGHTS “Targeting Life in Idlib” WATCH Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: https://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Map .................................................................................................................................. i Glossary .......................................................................................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

No. 213/20 September 2017

Syrian Crisis United Nations Response A Weekly Update from the UN Department of Public Information No. 213/20 September 2017 WHO speaks out against attacks on medical personnel and hospitals in Idlib province The World Health Organization (WHO) condemned the attacks on medical personnel and facilities in Idlib province on 19 September which reportedly killed and injured health workers and disrupted health services for thousands of people. According to WHO local partners, several ambulances and hospitals were hit by airstrikes within a few hours. All three hospitals in Kafr Nabl, Khan Sheikhoun and Heish sub-districts are no longer in service. “These attacks deprive civilians caught in the crossfire of the critical trauma care and health services they need. Every day, health workers risk their lives to care for the sick and wounded across the country. We must continue to protect and support them as they work to save lives”, said Dr Peter Salam, Executive Director of WHO Health Emergencies. WHO urges all parties to the conflict to refrain from attacking civilians and civilian infrastructure, as required by International Humanitarian Law. https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/who-condemns-attacks-hospitals-and- health-workers-idlib-and-hama Human rights investigative panel calls for perpetrators of human rights violations to be brought to justice Civilians continue to be deliberately attacked, deprived of humanitarian aid and essential healthcare services, forcibly displaced, and arbitrarily detained or held hostage by all warring parties, according to the latest report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria. Presenting the report to the Human Rights Council on 18 September, the Chair of the investigative panel, Paulo Pinheiro, appealed to all parties – pro-Government and international coalition alike – conducting airstrikes in Syria to ensure they are taking all efforts to spare civilians from harm and refrain from striking hospitals, schools, and religious sites. -

Human Rights Abuses and International Humanitarian Law Violations in the Syrian Arab Republic, 21 July 2016- 28 February 2017*

A/HRC/34/CRP.3 Distr.: Restricted 10 March 2017 English only Human Rights Council Thirty-fourth session 27 February-24 March 2017 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Human rights abuses and international humanitarian law violations in the Syrian Arab Republic, 21 July 2016- 28 February 2017* Conference room paper of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic Summary After almost six years of conflict, civilians continue to bear the brunt of the brutal violence waged by warring parties in the Syrian Arab Republic. Government and pro- Government forces continue to attack civilian objects including hospitals, schools and water stations. A Syrian Air Force attack on a complex of schools in Haas (Idlib), amounting to war crimes, is a painful reminder that instead of serving as sanctuaries for children, schools are ruthlessly bombed and children’s lives senselessly robbed from them. Government and pro-Government forces continue to use prohibited weapons including cluster munitions, incendiary weapons and weaponised chlorine canisters on civilian- inhabited areas, further illustrating their complete disregard for civilian life and international law. The terrorist group Jabhat Fatah al-Sham persists in carrying out summary executions including of women, and recruiting children in Idlib governorate. Coordinated attacks undertaken by the terrorist group alongside armed groups launched by indirect artillery fire resulted in dozens of civilian casualties, including many children. Life under the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) rule continues to be marked by executions and severe corporal punishments of civilians accused of violating the group’s ideology, and the destruction of cultural heritage sites including the Tetrapylon in Palmyra (Homs). -

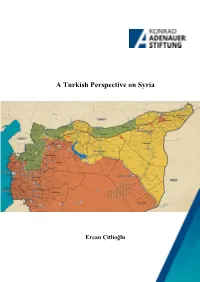

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

Security Council Distr.: General 22 April 2016

United Nations S/2016/368 Security Council Distr.: General 22 April 2016 Original: English Letter dated 21 April 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Saudi Arabia to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit a letter dated 21 April 2016 from the Special Representative of the Syrian National Coalition to the United Nations, Najib Ghadbian (see annex). I should be grateful if you would circulate the attached letter and its annex as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Abdallah Y. Al-Mouallimi Permanent Representative 16-06690 (E) 270416 *1606690* S/2016/368 Annex to the letter dated 21 April 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Saudi Arabia to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council On behalf of the High Negotiations Committee of the Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, and as requested by the Chief Coordinator of the Committee, Riad Hijab, it is my honour to transmit to you a letter from Riad Hijab dated 21 April 2016 (see enclosure), in which he discusses the violations of the cessation of hostilities agreement in Syria, with particular emphasis on the massacres of 19 April 2016. (Signed) Najib Ghadbian Special Representative of the Syrian National Coalition to the United Nations 2/6 16-06690 S/2016/368 Enclosure On behalf of the High Negotiations Committee of the Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, it is with great urgency that I draw your attention to the massacres in the Syrian towns of Kafr Nabl and Ma‘arrat al-Nu‘man, Idlib governorate, and the air strikes in Aleppo and Rif Dimashq committed by the Assad regime and its supporters on 19 April 2016. -

Idlib and Its Environs Narrowing Prospects for a Rebel Holdout REUTERS/KHALIL ASHAWI REUTERS/KHALIL

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ FEBRUARY 2020 ■ PN75 Idlib and Its Environs Narrowing Prospects for a Rebel Holdout REUTERS/KHALIL ASHAWI REUTERS/KHALIL By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi Greater Idlib and its immediate surroundings in northwest Syria—consisting of rural northern Latakia, north- western Hama, and western Aleppo—stand out as the last segment of the country held by independent groups. These groups are primarily jihadist, Islamist, and Salafi in orientation. Other areas have returned to Syrian government control, are held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), or are held by insurgent groups that are entirely constrained by their foreign backers; that is, these backers effectively make decisions for the insurgents. As for insurgents in this third category, the two zones of particular interest are (1) the al-Tanf pocket, held by the U.S.-backed Jaish Maghaweer al-Thawra, and (2) the areas along the northern border with Turkey, from Afrin in the west to Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain in the east, controlled by “Syrian © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. AYMENN JAWAD AL-TAMIMI National Army” (SNA) factions that are backed by in Idlib province that remained outside insurgent control Turkey and cannot act without its approval. were the isolated Shia villages of al-Fua and Kafarya, This paper considers the development of Idlib and whose local fighters were bolstered by a small presence its environs into Syria’s last independent center for insur- of Lebanese Hezbollah personnel serving in a training gents, beginning with the province’s near-full takeover by and advisory capacity.3 the Jaish al-Fatah alliance in spring 2015 and concluding Charles Lister has pointed out that the insurgent suc- at the end of 2019, by which time Jaish al-Fatah had cesses in Idlib involved coordination among the various long ceased to exist and the jihadist group Hayat Tahrir rebel factions in the northwest. -

THE 13TH ANNUAL REPORT on Human Rights in Syria 2014

The Syrian Committe for Human Rights THE 13TH ANNUAL REPORT On human rights in Syria 2014 (January 2014 – December 2014) JANUARY 2015 www.shrc.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 2 Genocide: daily massacres amidst international silence 8 Syrian Prisons: arbitrary detention, forced disappearance 54 and death from torture Violations committed against health and healthcare 48 Displacement: the Syrian crisis becomes an international 97 dilemma Violations against the education sector 79 The use of internationally prohibited weapons 905 Targeting the media and journalists 929 Targeting houses of worship 965 Legal and legislative amendments 989 Preface The year 2014 was a year that saw the violations committed against the Syrian people reach a dangerous level of continuity and repetition, to the extent that they no longer attract much public attention. Even crimes such as massacres and the use of internationally prohibited weapons have become part of the Syrian people's daily lives. The report shows continuity of all the violations committed last year and in some cases an increase in these violations. This excludes the use of chemical weapons, which was replaced this year by the use of poisonous gas. The year 2014 was the bloodiest in the last 4 years as more than 60.000 Syrians were killed this year alone. However, international and local reactions to these on-going violations were the weakest. One of the main factors that played a major role in Syria this year was the presence of the Islamic State in Iraq and Sham (ISIS). The largest massacre this year was committed by ISIS when it attacked the al-Sh'eitat tribe in August.