Murzaku's "Returning Home to Home: the Basilian Monks of Grottaferrata in Albania" - Book Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures by Sean Delaine Griffin 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Byzantine Liturgy and the Primary Chronicle by Sean Delaine Griffin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Gail Lenhoff, Chair The monastic chroniclers of medieval Rus’ lived in a liturgical world. Morning, evening and night they prayed the “divine services” of the Byzantine Church, and this study is the first to examine how these rituals shaped the way they wrote and compiled the Povest’ vremennykh let (Primary Chronicle, ca. 12th century), the earliest surviving East Slavic historical record. My principal argument is that several foundational accounts of East Slavic history—including the tales of the baptism of Princess Ol’ga and her burial, Prince Vladimir’s conversion, the mass baptism of Rus’, and the martyrdom of Princes Boris and Gleb—have their source in the feasts of the liturgical year. The liturgy of the Eastern Church proclaimed a distinctively Byzantine myth of Christian origins: a sacred narrative about the conversion of the Roman Empire, the glorification of the emperor Constantine and empress Helen, and the victory of Christianity over paganism. In the decades following the conversion of Rus’, the chroniclers in Kiev learned these narratives from the church services and patterned their own tales of Christianization after them. The ii result was a myth of Christian origins for Rus’—a myth promulgated even today by the Russian Orthodox Church—that reproduced the myth of Christian origins for the Eastern Roman Empire articulated in the Byzantine rite. -

Reflections on the Religionless Society: the Case of Albania

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 16 Issue 4 Article 1 8-1996 Reflections on the Religionless Society: The Case of Albania Denis R. Janz Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Janz, Denis R. (1996) "Reflections on the Religionless Society: The Case of Albania," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 16 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol16/iss4/1 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REFLECTIONS ON THE RELIGIONLESS SOCIETY: THE CASE OF ALBANIA By Denis R. Janz Denis R. Janz is professor of religious studies at Loyola University, New Orleans, · Louisiana. From the time of its inception as a discipline, the scientific study of religion has raised the question of the universality of religion. Are human beings somehow naturally religious? Has there ever been a truly religionless society? Is modernity itself inimical to religion, leading slowly but nevertheless inexorably to its extinction? Or does a fundamental human religiosity survive and mutate into ever new forms, as it adapts itself to the exigencies of the age? There are as of yet no clear answers to these questions. And religiologists continue to search for the irreligious society, or at least for the society in which religion is utterly devoid of any social significance, where the religious sector is a tiny minority made up largely of elderly people and assorted marginal figures. -

Some Symbols of Identity of Byzantine Catholics I Robert J

Some Symbols of Identity of Byzantine Catholics I Robert J. Skovira Introduction This essay is a descript�on of some of an ethnic group's symbols of identity2; itsa im is to explore the meanings of the following statement: [Byzantine Catholics] are no longer an immigrant and ethnic group. Byzantine Catholics are American in every sense of the word, that the rite itself is American as opposed to fo reign, and that both the rite and its adherents have become part and parcel of the American scene.;l This straight-forward statement claims that there ha been a rei nterpretation an d reexpression of identity within a new political and sociocultural envrionment.� It is common ense, for example, to think that individuals as a group do, re-do, rearrange, and change the expressions of values and beliefs in new situations. But, in order to ensure continuity in the midst of change, people will usually use already ex isting symbols-or whatever is at hand and fa miliar. Byzan tine Catholic identity is a case of new bottles with old wine. Ethnic groups and their members rely upon any number of factors to symbolize the values and beliefs with which they identify and by which they are identified. Such symbol of identity are manipulated, exploited, reinterpreted or changed, over time, according to the requirements of the context. In any event, people always use whatever is present to them for maintaining some continuity of identity while, at the same time, adjusting to new state -of-affairs. Herskovits shows, for exampl ,that We are dealing with a basi proce s in the adjustment of individual behavior and of institutional structures to be found in all situations where people having different ways of life come into con tact. -

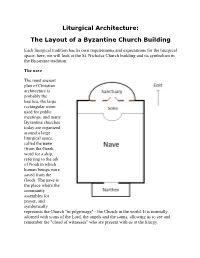

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

Eastern Rite Catholicism

Eastern Rite Catholicism Religious Practices Religious Items Requirements for Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals Sacred Writings Organizational Structure History Theology RELIGIOUS PRACTICES Required Daily Observances. None. However, daily personal prayer is highly recommended. Required Weekly Observances. Participation in the Divine Liturgy (Mass) is required. If the Divine Liturgy is not available, participation in the Latin Rite Mass fulfills the requirement. Required Occasional Observances. The Eastern Rites follow a liturgical calendar, as does the Latin Rite. However, there are significant differences. The Eastern Rites still follow the Julian Calendar, which now has a difference of about 13 days – thus, major feasts fall about 13 days after they do in the West. This could be a point of contention for Eastern Rite inmates practicing Western Rite liturgies. Sensitivity should be maintained by possibly incorporating special prayer on Eastern Rite Holy days into the Mass. Each liturgical season has a focus; i.e., Christmas (Incarnation), Lent (Human Mortality), Easter (Salvation). Be mindful that some very important seasons do not match Western practices; i.e., Christmas and Holy Week. Holy Days. There are about 28 holy days in the Eastern Rites. However, only some require attendance at the Divine Liturgy. In the Byzantine Rite, those requiring attendance are: Epiphany, Ascension, St. Peter and Paul, Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and Christmas. Of the other 15 solemn and seven simple holy days, attendance is not mandatory but recommended. (1 of 5) In the Ukrainian Rites, the following are obligatory feasts: Circumcision, Easter, Dormition of Mary, Epiphany, Ascension, Immaculate Conception, Annunciation, Pentecost, and Christmas. -

Byzantine Liturgical Hymnography: a Stumbling Stone for the Jewish-Orthodox Christian Dialogue? Alexandru Ioniță*

Byzantine Liturgical Hymnography: a Stumbling Stone for the Jewish-Orthodox Christian Dialogue? Alexandru Ioniță* This article discusses the role of Byzantine liturgical hymnography within the Jewish- Orthodox Christian dialogue. It seems that problematic anti-Jewish hymns of the Orthodox liturgy were often put forward by the Jewish side, but Orthodox theologians couldn’t offer a satisfactory answer, so that the dialogue itself profoundly suffered. The author of this study argues that liturgical hymnography cannot be a stumbling stone for the dialogue. Bringing new witnesses from several Orthodox theologians, the author underlines the need for a change of perspective. Then, beyond the intrinsic plea for the revision of the anti-Jewish texts, this article actually emphasizes the need to rediscover the Jewishness of the Byzantine liturgy and to approach the hymnography as an exegesis or even Midrash on the biblical texts and motives. As such, the anti-Jewish elements of the liturgy can be considered an impulse to a deeper analysis of Byzantine hymnography, which could be very fruitful for the Jewish-Christian Dialogue. Keywords: Jewish-Orthodox Christian Dialogue; Byzantine Hymnography; anti-Judaism; Orthodox Liturgy. Introduction The dialogue between Christian Orthodox theologians and Jewish repre- sentatives is by far one of the least documented and studied inter-religious interchanges. However, in recent years several general approaches to this topic have been issued1 and a complex study of it by Pier Giorgio Tane- burgo has even been published.2 Yet, because not all the reports presented at different Christian-Jewish joint meetings have been published and also, * Alexandru Ioniță, research fellow at the Institute for Ecumenical Research, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu. -

Byzantine Lutheranism!

Byzantine Lutheranism? Byzantine Lutheranism! Through the 1596 Union of Brest, many Ruthenian Orthodox bishops, with their eparchies, entered into communion with the Pope at Rome. They did this with the understanding that they and their successors would always be able to preserve their distinctive Eastern customs, such as a married priesthood, and the use of the Byzantine Rite for worship, in a language understood by the people. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church became (and remains) the heir of this 1596 union. The region of Galicia in eastern Europe (now a part of Ukraine), inhabited mostly by ethnic Ukrainians, was a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the end of the First World War. After a few years of regional conflict Galicia then came under the jurisdiction of a newly reconstituted Polish state. Soon thereafter, under pressure from the hierarchy of the Polish Roman Catholic Church and with the collusion of the Pope, the Stanyslaviv Eparchy of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Galicia began to undergo an imposed Latinization. This Latinization process manifested itself chiefly in the prohibition of any future ordinations of married men, and in the requirement that the Western Rite Latin Mass be used for worship. The Ukrainians who were affected by this felt betrayed, and many of them began to reconsider their ecclesiastical associations and allegiance to the Pope. This was the setting for the emergence of a Lutheran movement among the Ukrainians of this region, in the 1920s. This movement was initially prompted by two -

Rome's Last Efforts Towards the Union of Orthodox Albanians (1929-1946)

Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 58(1-2), 41-83. doi: 10.2143/JECS.58.1.2017736 © 2006 by Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. All rights reserved. ROME’S LAST EFFORTS TOWARDS THE UNION OF ORTHODOX ALBANIANS (1929-1946) INES ANGJELI MURZAKU* INTRODUCTION It would probably be improper to study the history of the Albanian Greek Catholic Church in unity with Rome in isolation from a concurrent move- ment, that is, the struggle to establish an Albanian Autocephalous Church. The two movements have something in common: they were both animated by the desire of the Albanian people for national identity. Indeed, Albania is not an isolated case scenario in ecclesiastical history. Analogous developments have taken place in other Eastern European countries; the case of Bulgaria is the classical example. The move of the Bulgarian Orthodoxy toward Rome was largely inspired by the wish to restore their national identity after cen- turies of coercion, not only by the Turks but also from the Greeks.1 In nine- teenth-century Bulgaria, when the struggle for autocephaly was gaining momentum, several influential Bulgarian Orthodox faithful in Constantino- ple began to contemplate union with Rome as a solution to their national problems. They thought that as Orthodox they would be able to revive their national ecclesiastical traditions, which they thought Constantinople had denied them.2 In fact, the Greeks were profoundly hated in Bulgaria, because * Ines Angjeli Murzaku is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Seton Hall Univer- sity in South Orange, New Jersey, an Adjunct Associate Professor of Historical Theology at the Graduate School of Theology, Immaculate Conception Seminary, and Lecturer at the Centro per l’Europa Centro-Orientale e Balcanica of the University of Bologna. -

Mythology and Destiny Albert Doja

Mythology and Destiny Albert Doja To cite this version: Albert Doja. Mythology and Destiny. Anthropos -Freiburg-, Richarz Publikations-service GMBH, 2005, 100 (2), pp.449-462. 10.5771/0257-9774-2005-2-449. halshs-00425170 HAL Id: halshs-00425170 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00425170 Submitted on 1 May 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. H anthropos 100.2005:449-462 1^2 Mythologyand Destiny AlbertDoja Abstract.- In Albaniantradition, the essential attributes of larlyassociated with the person's spirit, with their the mythologicalfigures of destinyseem to be symbolic lifeand death,their health, their future character, interchangeablerepresentations of birth itself. Their mythical theirsuccesses and setbacks. the combatis butthe symbolic representation of the cyclic return Theysymbolize in thewatery and chthonianworld of death,leading, like the person'sproperties, are thespiritual condensation vegetation,tothe cosmic revival of a newbirth. Both protective of theirqualities. They have suchclose mystical anddestructive positions of theattributes of birth,symbolized tieswith the person that merely the way they are by the amnioticmembranes, the caul, and othersingular dealtwith or theaim are ascribeddetermines ofmaternal they markers,or by the means of the symbolism water, theindividual's own and fate. -

Country Advice Albania Albania – ALB36773 – Greece – Orthodox Christian Church – Baptisms – Albania – Church Services – Tirana – Trikala 9 July 2010

Country Advice Albania Albania – ALB36773 – Greece – Orthodox Christian Church – Baptisms – Albania – Church services – Tirana – Trikala 9 July 2010 1. Please search for information on Greece in relation to whether a person cannot be baptised Orthodox if they are illegally in Greece. Information regarding whether a person cannot be baptised Orthodox if they are illegally in Greece was not located in a search of the sources consulted. The Greek constitution establishes the Eastern Orthodox Church of Christ (Greek Orthodox Church) as the prevailing religion in Greece and it was estimated that 97 percent of the population identified itself as Greek Orthodox. The Greek Orthodox Church exercises significant influence and “[m]any citizens assumed that Greek ethnicity was tied to Orthodox Christianity. Some non-Orthodox citizens complained of being treated with suspicion or told that they were not truly Greek when they revealed their religious affiliation.”1 It is reported that most of Greece‟s native born population are baptised into the Orthodox Church.2 A 2004 report indicates that the “Orthodox Church takes on the self anointed role as keeper of the national identity”. The report refers to the comments of a priest in Athens who said that “in Greece, we regard Greeks as the ones who are baptised” and people who were not baptised, immigrants, were not seen as Greek.3 2. Please provide information generally about the Orthodox Church in Albania including, if possible, details about the order of the church service. The Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania is one of four traditional religious groups in Albania. The majority of Albanians do not actively practice a faith,4 but it is estimated that 20 to 25 percent of the Albanian population are in communities that are traditionally Albanian Orthodox. -

Download Download

DOI https://doi.org/10.36059/978-966-397-100-1/164-183 MONASTERIES OF WESTERN DIOCESES OF KYIV UNION METROPOLIYA (90th YEARS OF XVII – 90th YEARS OF XVIII CENTURES): JURISDICTIONAL CONVERSIONS Stetsyk Y. O. INTRODUCTION In today’s conditions of building a netting of Basilian monasteries, it becomes necessary to turn to the historical experience of managing monastic communities. After all, the system of administrative management of the Christian ascetic centers has undergone a certain evolution from the complete autonomy (each monastery had its own charter and was independent of each other) to the gradual legal submission to the local bishops first, and subsequently there was a re-subordination to the newly formed authorities of the Proto-Hegumen and the Proto-Archimandrite. The introduction of these governing institutions in the Union Church allowed the creation of an autonomous system of administrative control of the Basilian monasticism, which was subjected neither to the local rulers nor to the Metropolitan of Kiev, and instead it was subjected to papal law. The answer to this right applies to all provinces of the Basilian Order subordinated to the Pope. The considered management system was borrowed from the administrative organization of the Roman Catholic monasteries for a more effective manner of union monastic communities. Accordingly, in our time, when there is a reform of the system of governance, the conditional development of church institutions and the development of society is reflected in the regular updating of the Constitutions of the Order of St. Basil the Great (hereinafter OSBM), it becomes necessary to examine the historical and legal aspects of the establishment of governance institutions that continue to operate in the modern Greek-Catholic Church, which is considered to be the successor to the Union Church. -

American Protestantism and the Kyrias School for Girls, Albania By

Of Women, Faith, and Nation: American Protestantism and the Kyrias School For Girls, Albania by Nevila Pahumi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Pamela Ballinger, Co-Chair Professor John V.A. Fine, Co-Chair Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Mary Kelley Professor Rudi Lindner Barbara Reeves-Ellington, University of Oxford © Nevila Pahumi 2016 For my family ii Acknowledgements This project has come to life thanks to the support of people on both sides of the Atlantic. It is now the time and my great pleasure to acknowledge each of them and their efforts here. My long-time advisor John Fine set me on this path. John’s recovery, ten years ago, was instrumental in directing my plans for doctoral study. My parents, like many well-intended first generation immigrants before and after them, wanted me to become a different kind of doctor. Indeed, I made a now-broken promise to my father that I would follow in my mother’s footsteps, and study medicine. But then, I was his daughter, and like him, I followed my own dream. When made, the choice was not easy. But I will always be grateful to John for the years of unmatched guidance and support. In graduate school, I had the great fortune to study with outstanding teacher-scholars. It is my committee members whom I thank first and foremost: Pamela Ballinger, John Fine, Rudi Lindner, Müge Göcek, Mary Kelley, and Barbara Reeves-Ellington.