Constraints Experienced by Elite Athletes with Disabilities in Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conserving Wildlife in African Landscapes Kenya’S Ewaso Ecosystem

Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press smithsonian contributions to zoology • number 632 Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press AConserving Chronology Wildlife of Middlein African Missouri Landscapes Plains Kenya’sVillage Ewaso SitesEcosystem Edited by NicholasBy Craig J. M. Georgiadis Johnson with contributions by Stanley A. Ahler, Herbert Haas, and Georges Bonani SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of “diffusing knowledge” was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: “It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge.” This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com- mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to History and Technology Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report on the research and collections of its various museums and bureaus. The Smithsonian Contributions Series are distributed via mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institu- tions throughout the world. Manuscripts submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press from authors with direct affilia- tion with the various Smithsonian museums or bureaus and are subject to peer review and review for compliance with manuscript preparation guidelines. -

Kenya.Pdf 43

Table of Contents PROFILE ..............................................................................................................6 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Facts and Figures.......................................................................................................................................... 6 International Disputes: .............................................................................................................................. 11 Trafficking in Persons:............................................................................................................................... 11 Illicit Drugs: ................................................................................................................................................ 11 GEOGRAPHY.....................................................................................................12 Kenya’s Neighborhood............................................................................................................................... 12 Somalia ........................................................................................................................................................ 12 Ethiopia ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 Sudan.......................................................................................................................................................... -

Impact of Sporting Activities on the Environment in Kenya: Proposal for a Specific Policy on Sports and Environment

Impact of Sporting Activities on the (2021) Journalofcmsd Volume 6(1)) Environment in Kenya: Proposal for a Specific Policy on Sports and Environment: Caroline Shisubili Maingi & Mercury Shitindo Impact of Sporting Activities on the Environment in Kenya: Proposal for a Specific Policy on Sports and Environment By: Caroline Shisubili Maingi* & Mercury Shitindo* Abstract Sport is a necessary part of life that is intricately interconnected to the environment. On one hand, sports need a good environment to be played on whilst at the same time, sports through its activities affects the environment. When the world was hit with a global pandemic in 2019, sports was one of the areas that was most affected. With the encouragement of social and physical distance as a means of reducing infection rates and limiting physical contact in sports, it also acted as a period of restoration of the environment. This article emphasizes how sport promotes good health, physical fitness, mental well-being, social interaction and contributes to the socio-economic, political and cultural development of a country. The article highlights how sports can attract infrastructure that requires heavy machinery that can impact the environment negatively, this in addition to the economic activities linked to it, and how this directly affects man. The article delves into sports in Kenya identifying how there are no clear guidelines on how to do sports while taking care of the environment. The study will recommend policies that will encourage a balance between having sports while also giving consideration to the environment. 1. Introduction Sport, like any other human activity, is set in the physical environment and is bound to have effects on it and be affected by it. -

Music, Dance and Sports in Kenya. Traditional Music and Dance of Kenyan Communities

Music, dance and sports in Kenya. Traditional music and dance of Kenyan communities. By Naomi Wachuka Kiai .Music was a part of everyday life in traditional African INTRODUCTION. communities. It was as a result of the desire of the people to express different feelings. .Occasions for music making include ceremonies for rites of passage, successful raids/ wars, sacred ceremonies and wedding ceremonies. Traditional Akamba dance. SOLO EDUCATIVE DANCE ORGAISATION OF MUSIC AND DANCE. VOCAL TECHNIQUES. INSTRUMENTS. DANCE PATTERNS. Maasai traditional dance. The chivoti and nzumari of the Mijikenda community. The emouo, a horn of the Maasai community. The adongo, a plucked ideophone of the Iteso community. The Obokano. This is an eight-stringed Gusii lyre. The litungu, a Luhya lyre. It is smaller than the Obokano of the Gusii. A raft zither, makhana of the Marachi community. The orutu, a fiddle of the Luo community. The Ajawa. This is a Luo hand-held rattle. The Adeudeu, an Iteso harp. The mabubumbu, Mijikenda drums. Peke, Luo rattle. CONT. • A certain criteria is used in the classification of Kenyan instruments. The main factors are: 1. The external and internal basic shape of the instruments. 2. The mode of sound production. 3. The material used. 4. The mode of tuning the instrument. 5. The mode of holding the instrument. 6. The role of the instrument in the community. Kenyan traditional dance Different communities have different dances for different occasions. Dance is a series of body movements in response to musical stimuli. Kikuyu female dance. • Some characteristics of Kenyan traditional music are the music was gender specific, there was no definite pitching pattern and the most common style of singing was the call and response style. -

The Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXII—No. 126 NAIROBI, 3rd December, 2010 Price Sh. 50 GAZETTE NOTICE NO.15883 Certificate Number Name ofNGO THE NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS CO- OP. 218/051/2001/0236/2001 Africa Co - Operation And ORDINATION ACT Development Programme (No. 19 of 1990) OP.218/05 1/2003/0464/3094 Africa Community Development Foundation CANCELLATION OF REGISTRATION CERTIFICATES OP.O/2 18/05 1/0185/1685 Africa Cultural Relief Organization OP.218/05 1/2003/0422/2983 Africa Development And NOTICE is hereby given pursuant to section 16 of the Non- Education Foundation Governmental Organizations Co-ordination Act, which the Non- OP.218/05 1/2002/0111/2427 Africa Development Consortium Governmental Organizations Co-ordination Board intends to Cancel OP.218/05 1/9643/738 Africa Focus the Registration Certificates of the Non-Governmental Organizations OP. 218/051/2005/0239/3654 Africa Nature Stream listed in the schedule hereto on the grounds that they have breached OP.218/051/97167/1047 Africa Old Age Network - Kenya the provisions of the Non-Governmental Organizations Act of 1990 OP.218/05 1/96127/734 Africa Partnership Aid For and violated the terms or conditions attached to their certificates. Rehabilitation And Development Cancellation of the said certificates shall take effect after fourteen (14) OP.218/05 1/93224/303 Africa Recovery Team days after the date of this notice. OP.218/05 1/9268/36 Africa Rehabilitation & Education SCHEDULE Programme (Arep - Foundation) OP.218/05 1/2005/019/3532 Africa Resource Development Technologies (Afridet) Certificate Number Name ofNGO OP. -

CAPSTONE 20-2 Africa Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-2 Africa Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Djibouti ....................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 2 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 21 Culture Gram .......................................................... 26 Kenya ......................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 35 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 56 Culture Gram .......................................................... 60 Niger .......................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 70 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 90 Culture Gram .......................................................... 94 Senegal ...................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 103 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 123 Culture Gram .......................................................... 128 Africa :: Djibouti — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency Page 1 of 19 AFRICA :: DJIBOUTI Introduction :: DJIBOUTI Background: The French Territory of the Afars and the Issas became Djibouti in 1977. Hassan Gouled APTIDON installed an authoritarian one-party state and proceeded to serve as president -

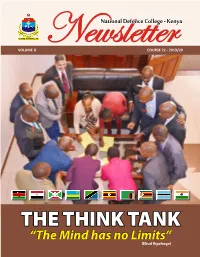

Course 22 Newsletter Volume 2

National Defence College - Kenya VOLUME II NewsletterCOURSE 22 - 2019/20 THE THINK TANK “The Mind has no Limits” (Eliud Kipchoge) Course 22 in traditional attire during the Cultural Day. Contents National Defence College - Kenya From the Commandant’s Desk ................................................................ 3 COURSE 22 - 2019/20 Newsletter Message from the Sponsor SDS .............................................................. 4 VOLUME II Message from the Chairman Editorial Board .......................................... 5 ‘Water Security’future in the Nile River Basin ........................................ 6 Diplomatic Intelligence ........................................................................... 7 Circumcision Rite Among the Bukusu Community .................................. 9 Social and Recreation Benefits .............................................................. 10 A Tour To Masai Mara ........................................................................... 12 Rethinking Strategically for Development ............................................. 13 Transition Reality: Change Is Inevitable: Old Cheese vs New Cheese ... 15 Kenya’s Food Security: The Role of Science, Technology and Innovation ... 16 THE THINK TANK(Eliud Kipchoge) “The Mind has no Limits” Kenya’s Wildlife Protected Areas – Havens of Ecosystem Services to Mankind ........................................... 18 The Importance of The Media in Influencing Foreign Policy ................. 20 Protect Yourself .................................................................................... -

When Celebrity Athletes 2015, Vol

IRS0010.1177/1012690213506005International Review for the Sociology of SportWilson et al. 5060052013 Article International Review for the Sociology of Sport When celebrity athletes 2015, Vol. 50(8) 929 –957 © The Author(s) 2013 are ‘social movement Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav entrepreneurs’: A study of the DOI: 10.1177/1012690213506005 irs.sagepub.com role of elite runners in run-for- peace events in post-conflict Kenya in 2008 Brian Wilson University of British Columbia, Canada Nicolien Van Luijk University of British Columbia, Canada Michael K Boit Kenyatta University, Kenya Abstract This paper reports findings from a study of the role played by high-profile Kenyan runners in the organization of Run-for-Peace events that took place in response to election-related violence in Kenya in late 2007 and early 2008. Acknowledging concerns expressed by some sociologists of sport about the role of celebrity athletes in the sport for development and peace movement, we suggest that in the particular contexts we studied, high-profile athletes played a crucial role in the organization of reconciliation events. Informed by interviews with former and current elite Kenyan runners and others involved in the organization of these events, we argue that the apparent effectiveness of the athletes in mobilizing resources, pursuing political opportunities and devising a collective action frame was possible because of the extant positioning of the athletes in the impacted communities, the active involvement in and personal investment of the athletes in the outcome of the peace-promoting activities, and the unique pre-Olympic moment in which the events took place. -

2020 History Booklet

CEKENA 311/1 HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT PAPER 1 SECTION A: (25 MARKS) Answer all the questions in this section in the booklet provided 1. What is oral tradition as a source of History? (1 mark) 2. Identify the main economic activity of the Akamba during the pre-colonial period. (1 mark) 3. Identify two natural factors that caused the Abagusii to migrate from Mount Elgon region to their present homeland. (2 marks) 4. Identify the town that was established by missionaries in Kenya as a centre for freed slaves during the 19th century. (1 mark) 5. Give two categories of persons who qualify to become Kenyan citizens by registration (2marks) 6. Identify one economic cause of conflicts in Kenya. (1 mark) 7. State one way in which direct democracy is exercised in Kenya (1 mark) 8. Give the main provision of the Independence Constitution of Kenya (1 mark) 9. Identify two powers granted to the Imperial British East Africa Company through the royal charter in 1887. (2 marks) 10. Identify two communities which portrayed mixed reactions towards the British occupation of Kenya (2 marks) 11. State the main reason why the white settlers were disappointed with the Devonshire White Paper of 1923 (1 mark) 12. State two similar grievances of the Taita Hills Association and the Ukamba Members Association to the colonial government. (2 marks) 13. State the main reason why the Second Lancaster House Conference was held in1962 (1 mark) 14. Identify two independent school associations established in central Kenya during the colonial period (2marks) 15. Name the two branches of National Police Service in Kenya. -

Materials and Methods

Materials and Methods Permissions and sampling protocols Permissions to conduct research and to export samples for destructive analysis Permission to conduct research in Kenya was obtained from the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI permit P/17/34239/17088 issued to MEP), through affiliation with the National Museums of Kenya (NMK). Permission to export skeletal samples for destructive sampling was issued by the Cabinet Secretary, Ministry of Sports and Heritage. Permission to conduct research in Tanzania was granted by the Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH permits 2017-220/221/222-NA-2012-50 issued to MEP/EAS/JO), through affiliation with the National Museums of Tanzania (NMT). Permission to export skeletal samples for destructive sampling was granted by the Division of Antiquities, Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (Export License 03/2018/2019). Permission to conduct research in the Livingstone Museum, Zambia was granted by the Director of the Museum. Permissions to loan and sample skeletal remains for destructive sampling were received from the Director and from the National Heritage Conservation Commission (Permit NHCC/8WR/004/17). Skeletal sampling protocols Samples were selected following protocols outlined in detail by (53). In brief: 1) Skeletons were chosen for sampling based upon their relevance to archaeological questions, preservation, available context information, and geographic location, among other factors. 2) No more than two skeletal tissue samples (bone and/or tooth) were selected per individual. In the vast majority of cases, the second sample, taken as a backup for aDNA or radiocarbon dating, was returned without having been sampled. 3) Samples were chosen to maximize aDNA success by preferentially choosing petrous or tooth, or where unavailable, dense postcranial bone; and by using appropriate protections to minimize contamination with modern DNA. -

U.S.-Kenya Relations: Current Political and Security Issues

U.S.-Kenya Relations: Current Political and Security Issues -name redacted- Specialist in African Affairs July 23, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R42967 U.S.-Kenya Relations: Current Political and Security Issues Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Political Background ....................................................................................................................... 2 Justice and Reconciliation ......................................................................................................... 3 The New Constitution ................................................................................................................ 5 The 2013 Elections .................................................................................................................... 5 Recent Political Developments .................................................................................................. 7 The Economy ................................................................................................................................... 8 Regional Security Dynamics ......................................................................................................... 10 U.S.-Kenya Relations .................................................................................................................... 12 U.S. Assistance ....................................................................................................................... -

Soccer Is Kenya's Most Popular Sport, Watched by Almost Every Kenyan

Dan Siegehnan History 91 12/22/2018 Political Goals: Soccer as a Langnage of Politics in Kenya Soccer is Kenya's most popular sport, watched by almost every Kenyan Soccer has a long history in Kenya, beginning with its introduction in the colonial period, when it was used by British colonists as a way to teach Kenyans European morals and values, In the postcolonial period, football was a similar political tool for Kenyan nationalist leaders, who built a sense ofKenyan identity on the back ofthe national team, But the Kenyan team has largely failed to produce results based on its level of support Faced with political challenges like corruption and the persecution of dissidents, soccer has emerged as a coded language for discussing politics, Football allows Kenyans to discuss the issues facing their country without fear, and this essay tries to understand what the game means not just as a political tool, but as a part ofKenyan life, Aden Marwa Range was set to be the only Kenyan referee at the 2018 World Cup in Russia, a proud moment for a nation whose rabid support of their soccer team has not been matched by its success on the international stage, Then, on June 7th, the BBC released footage of Marwa Range accepting a bribe from an undercover journalist, about $600 to fix a match at the African Nations Championship earlier that year. 1 On the eve of the tournament, the expose shocked the world, and led to a reexamination of the state of African football. Nowhere was this more true than in Marwa Range's home country, Kenya.