Strat-O-Matic Negro League All-Stars Guide Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbered Panel 1

PRIDE 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E The African-American Baseball Experience Cuban Giants season ticket, 1887 A f r i c a n -American History Baseball History Courtesy of Larry Hogan Collection National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 1 8 4 5 KNICKERBOCKER RULES The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club establishes modern baseball’s rules. Black Teams Become Professional & 1 8 5 0 s PLANTATION BASEBALL The first African-American professional teams formed in As revealed by former slaves in testimony given to the Works Progress FINDING A WAY IN HARD TIMES 1860 – 1887 the 1880s. Among the earliest was the Cuban Giants, who Administration 80 years later, many slaves play baseball on plantations in the pre-Civil War South. played baseball by day for the wealthy white patrons of the Argyle Hotel on Long Island, New York. By night, they 1 8 5 7 1 8 5 7 Following the Civil War (1861-1865), were waiters in the hotel’s restaurant. Such teams became Integrated Ball in the 1800s DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD DECISION NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BA S E BA L L PL AY E R S FO U N D E D lmost as soon as the game’s rules were codified, Americans attractions for a number of resort hotels, especially in The Supreme Court allows slave owners to reclaim slaves who An association of amateur clubs, primarily from the New York City area, organizes. R e c o n s t ruction was meant to establish Florida and Arkansas. This team, formed in 1885 by escaped to free states, stating slaves were property and not citizens. -

Jan-29-2021-Digital

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 64, No. 2 Friday, Jan. 29, 2021 $4.00 Innovative Products Win Top Awards Four special inventions 2021 Winners are tremendous advances for game of baseball. Best Of Show By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Editor/Collegiate Baseball Awarded By Collegiate Baseball F n u io n t c a t REENSBORO, N.C. — Four i v o o n n a n innovative products at the recent l I i t y American Baseball Coaches G Association Convention virtual trade show were awarded Best of Show B u certificates by Collegiate Baseball. i l y t t nd i T v o i Now in its 22 year, the Best of Show t L a a e r s t C awards encompass a wide variety of concepts and applications that are new to baseball. They must have been introduced to baseball during the past year. The committee closely examined each nomination that was submitted. A number of superb inventions just missed being named winners as 147 exhibitors showed their merchandise at SUPERB PROTECTION — Truletic batting gloves, with input from two hand surgeons, are a breakthrough in protection for hamate bone fractures as well 2021 ABCA Virtual Convention See PROTECTIVE , Page 2 as shielding the back, lower half of the hand with a hard plastic plate. Phase 1B Rollout Impacts Frontline Essential Workers Coaches Now Can Receive COVID-19 Vaccine CDC policy allows 19 protocols to be determined on a conference-by-conference basis,” coaches to receive said Keilitz. -

EARNING FASTBALLS Fastballs to Hit

EARNING FASTBALLS fastballs to hit. You earn fastballs in this way. You earn them by achieving counts where the Pitchers use fastballs a majority of the time. pitcher needs to throw a strike. We’re talking The fastball is the easiest pitch to locate, and about 1‐0, 2‐0, 2‐1, 3‐1 and 3‐2 counts. If the pitchers need to throw strikes. I’d say pitchers in previous hitter walked, it’s almost a given that Little League baseball throw fastballs 80% of the the first pitch you’ll see will be a fastball. And, time, roughly. I would also estimate that of all after a walk, it’s likely the catcher will set up the strikes thrown in Little League, more than dead‐center behind the plate. You could say 90% of them are fastballs. that the patience of the hitter before you It makes sense for young hitters to go to bat earned you a fastball in your wheelhouse. Take looking for a fastball, visualizing a fastball, advantage. timing up for a fastball. You’ll never hit a good fastball if you’re wondering what the pitcher will A HISTORY LESSON throw. Visualize fastball, time up for the fastball, jump on the fastball in the strike zone. Pitchers and hitters have been battling each I work with my players at recognizing the other forever. In the dead ball era, pitchers had curveball or off‐speed pitch. Not only advantages. One or two balls were used in a recognizing it, but laying off it, taking it. -

Class 2 - the 2004 Red Sox - Agenda

The 2004 Red Sox Class 2 - The 2004 Red Sox - Agenda 1. The Red Sox 1902- 2000 2. The Fans, the Feud, the Curse 3. 2001 - The New Ownership 4. 2004 American League Championship Series (ALCS) 5. The 2004 World Series The Boston Red Sox Winning Percentage By Decade 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 .522 .572 .375 .483 .563 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 .510 .486 .528 .553 .521 2001-10 11-17 Total .594 .549 .521 Red Sox Title Flags by Decades 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 1 WS/2 Pnt 4 WS/4 Pnt 0 0 1 Pnt 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 0 1 Pnt 1 Pnt 1 Pnt/1 Div 1 Div 2001-10 11-17 Total 2 WS/2 Pnt 1 WS/1 Pnt/2 Div 8 WS/13 Pnt/4 Div The Most Successful Team in Baseball 1903-1919 • Five World Series Champions (1903/12/15/16/18) • One Pennant in 04 (but the NL refused to play Cy Young Joe Wood them in the WS) • Very good attendance Babe Ruth • A state of the art Tris stadium Speaker Harry Hooper Harry Frazee Red Sox Owner - Nov 1916 – July 1923 • Frazee was an ambitious Theater owner, Promoter, and Producer • Bought the Sox/Fenway for $1M in 1916 • The deal was not vetted with AL Commissioner Ban Johnson • Led to a split among AL Owners Fenway Park – 1912 – Inaugural Season Ban Johnson Charles Comiskey Jacob Ruppert Harry Frazee American Chicago NY Yankees Boston League White Sox Owner Red Sox Commissioner Owner Owner The Ruth Trade Sold to the Yankees Dec 1919 • Ruth no longer wanted to pitch • Was a problem player – drinking / leave the team • Ruth was holding out to double his salary • Frazee had a cash flow crunch between his businesses • He needed to pay the mortgage on Fenway Park • Frazee had two trade options: • White Sox – Joe Jackson and $60K • Yankees - $100K with a $300K second mortgage Frazee’s Fire Sale of the Red Sox 1919-1923 • Sells 8 players (all starters, and 3 HOF) to Yankees for over $450K • The Yankees created a dynasty from the trading relationship • Trades/sells his entire starting team within 3 years. -

Hitting Mechanics 101

Hitting Mechanics 101 BAT SELECTION & GRIPPING THE BAT When selecting a bat: • Find a bat you can handle. Too many players use bats that are too big for them. • Select a bat that you can choke up on a little. When gripping a bat: • Hold the bat in your fingers • Line up the middle knuckles NOTE: Holding the bat too far in the palm of the hand will prevent you from maximizing the wrist snap during your swing. PREPARATION: 1. Take practice swings by swinging the bat down to the contact point and then bring it back to the shoulder. 2. Take eyes from mound to plate as you practice swing. 3. Make sure you bring hands back before going forward on swing. 4. Take short, quick swings while pitcher is getting the sign from the catcher. 5. Once pitcher starts wind up bring hands back up to top of the zone and get them still. 6. Don’t wiggle bat. Get your hands still when pitcher throws the ball so you can go right into Trigger Stride position. Hitting Mechanics 101 STANCE 1. Maintain a wide base – set up with your feet more than shoulder-width apart to gain balance and to avoid over-striding. 2. Knees should be inside ankles. Weight should be on the balls of the feet. 3. Bend at the knees and the waist. 4. Hands should be at the top of the strike zone. 5. Elbows should point toward the ground. (Holding the back elbow up can lead to a loop in the swing.) 6. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Negro Leaguers in Service If They Can Fight and Die on Okinawa and Guadalcanal in the South Pacific, They Can Play Baseball in America

Issue 37 July 2015 Negro Leaguers in Service If they can fight and die on Okinawa and Guadalcanal in the South Pacific, they can play baseball in America. Baseball Commissioner AB "Happy" Chandler This edition of the Baseball in Wartime Newsletter is dedicated to all the African- American baseball players who served with the armed forces during World War II. More than 200 players from baseball’s Negro Leagues entered military service between 1941 and 1945. Some served on the home front, while others were in combat in Europe, North Africa and the Pacific. These were the days of a segregated military and life was never easy for these men, but, for some, playing baseball made the summer days a little more bearable. Willard Brown and Leon Day (the only two black players on the team) helped the OISE All-Stars win the European Theater World Series in 1945, Joe Greene helped the 92nd Infantry Division clinch the Mediterranean Theater championship the same year, Jim Zapp was on championship teams in Hawaii in 1943 and 1944, and Larry Doby, Chuck Harmon, Herb Bracken and Johnny Wright were Midwest Servicemen League all- stars in 1944. Records indicate that no professional players from the Negro Leagues lost their lives in service during WWII, but at least two semi-pro African-American ballplayers made the ultimate sacrifice. Grady Mabry died from wounds in Europe in December 1944, and Aubrey Stewart was executed by German SS troops the same month. With Brown and Day playing for the predominantly white OISE All-Stars, Calvin Medley pitching for the Fleet Marine Force team in Hawaii, and Don Smith pitching alongside former major leaguers for the Greys in England, integrated baseball made its appearance during the war years and quite possibly paved the way for the signing of Jackie Robinson. -

Rules and Equipment Rules and Equipment 71

7 Rules and Equipment Rules and Equipment 71 n this chapter we introduce you to some of the basic rules of Babe Ruth League, Inc. We don’t try to cover all the rules of the game, but rather we Igive you what you need to work with players who are 4 to 18 years old. We provide information on terminology, equipment, field size and markings, player positions, and game procedures. In a short section at the end of the chapter we show you the umpire’s signals for Babe Ruth Baseball. Terms to Know Baseball has its own vocabulary. Be familiar with the following common terms to make your job easier. In some cases we go into more depth on terms to explain related rules. appeal—The act of a fielder in claiming violation of the rules by the offensive team; this most commonly occurs when a runner is thought to have missed a base. balk—An illegal motion by the pitcher intended to deceive the baserunners resulting in all runners advancing one base as determined by the umpire. ball—A pitch that the batter doesn’t swing at and that is outside of the strike zone. base—One of four points that must be touched by a runner in order to score. base coach—A team member or coach who is stationed in the coach’s box at first or third base for the purpose of directing the batter and runners. base on balls—An award of first base granted to a batter who, during his or her time at bat, receives four pitches outside the strike zone before receiving three pitches inside the strike zone. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Ernie Banks

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Ernie Banks PERSON Banks, Ernie, 1931- Alternative Names: Ernie Banks; Ernest Banks Life Dates: January 31, 1931-January 23, 2015 Place of Birth: Dallas, Texas, USA Residence: Marina Del Rey, CA Occupations: Baseball Player Biographical Note Baseball player Ernie Banks was born in Dallas, Texas, on January 31, 1931. As legend has it, his father had to bribe young Ernie with nickels and dimes in order to get his son to play catch. An all-around athlete, Banks was a high school star in football, basketball and track. At age seventeen, he signed to play baseball with a Negro barnstorming team. Manager Cool Papa Bell recognized Banks’ talent and signed him to a contract with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Baseball League. City Monarchs of the Negro Baseball League. In 1953, Banks was recruited directly from the Negro League into the majors with the Chicago Cubs. He hit his first home run on September 20, 1953, beginning a long career as one of the Cubs’ most beloved players. From 1955 to 1960, Ernie Banks hit more homers than anyone in the majors, including Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron, and he finished his career with five seasons of forty or more home runs. In 1959 he became the first player in National League history to win consecutive Most Valuable Player trophies, a year removed from setting an NL record for homers by a shortstop with forty-seven. After retiring from the major leagues as a career Cub in 1971, Banks became the first Cub to have his uniform number retired. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

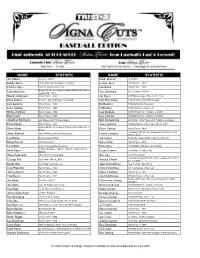

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Negro Southern League Museum Research

Negro Southern League (1920-1951) It was common practice for the teams in the league to all play a different number of games during the season. Standings are presented based on winning percentage for the entire season in “league” games only. Negro Southern League (1920) Newspaper accounts differ in the final standings of the teams that played in the Negro Southern League in 1920. Part of the difference in records reported by Southern newspapers revolved around whether or not certain forfeited games were counted or not counted in a team’s won-loss record. On September 11, 1920 The Chicago Defender reported the following Negro Southern League standings: 1920 Games Record Pct. Knoxville Giants 76 55-21 .724 Montgomery Grey Sox 86 47-39 .547 Atlanta Black Crackers 84 45-39 .536 Birmingham Black Barons 82 43-39 .524 New Orleans Caulfield Ads 82 43-39 .524 Nashville White Sox 80 40-40 .500 Jacksonville Stars 44 18-26 .409 For some explained reason, the Pensacola Giants were left out of the standings. Speculation is that it was a dropped line of type when the newspaper was put together. On September 12, 1920, the Alabama Journal of Montgomery, Alabama reported the following Negro Southern League standings: 1920 Games Record Pct. Montgomery Grey Sox 98 48-40 .545 Knoxville Giants 64 34-30 .531 New Orleans Caulfield Ads 83 44-39 .530 Birmingham Black Barons 82 43-39 .524 Atlanta Black Crackers 89 45-44 .505 Nashville White Sox 80 40-40 .500 Pensacola Giants 83 40-43 .482 Jacksonville Stars 44 18-26 .409 Notes: 1. -

William Bell

Forgotten Heroes: William Bell by Center for Negro League Baseball Research Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz Copyright 2014 Kansas City Monarchs (1924) Negro National League and Negro League World Series Champions ((Lemuel Hawkins, William Bell, Clifford Bell, Carroll “Dink” Mothel, Frank Duncan (Sr.), William “Plunk” Drake, George Sweatt and Homer “Hop” Bartlett) (Jack Marshall, Hurley McNair, Newt Joseph, Harold “Yellowhorse” Morris, Oscar “Heavy” Johnson, Newt Allen, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan, Jose Mendez and Walter “Dobie” Moore) William Bell, Sr. was born on August 31, 1897 in Lavaca County, Texas. He stood 5’ 11” tall and weighed 180 pounds during his playing career. Bell was a right-handed pitcher who was one of the best pitchers in Negro League baseball during the 1920’s. On the mound he was known for his consistency, excellent control and ability to paint the corners. William had command of a wide range of pitches. He had an active fastball that moved in on the hitter, a very good curve ball, a good change-up and slider. During the 1920’s he was a workhorse for the Kansas City Monarchs during their championship seasons. Bell was also known for completing what he started during his career. Our research has revealed that he completed over 75 % of the games he started. In addition William Bell had a reputation for always being able to deliver in the clutch and under pressure. During his career he was occasionally called on to play in the outfield because he was a decent hitter and very good fielder. He had his best two years at the plate in 1929 when he hit .296 and 1932 when he batted .295.