Considerations on the Allergy-Risks Related to the Consumption of Fruits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stomata Size in Relation to Ploidy Level in North American Hawthorns (Crataegus, Rosaceae) Author(S): Brechann V

Stomata Size in Relation to Ploidy Level in North American Hawthorns (Crataegus, Rosaceae) Author(s): Brechann V. McGoey Kelvin Chau Timothy A. Dickinson Source: Madroño, 61(2):177-193. 2014. Published By: California Botanical Society DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3120/0024-9637-61.2.177 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3120/0024-9637-61.2.177 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. MADRON˜ O, Vol. 61, No. 2, pp. 177–193, 2014 STOMATA SIZE IN RELATION TO PLOIDY LEVEL IN NORTH AMERICAN HAWTHORNS (CRATAEGUS,ROSACEAE) BRECHANN V. MCGOEY Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada M5S 3B2 [email protected] KELVIN CHAU Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 1124 Finch Ave. W, Unit 2, Toronto, ON, Canada M3J 2E2 TIMOTHY A. DICKINSON Green Plant Herbarium (TRT), Department of Natural History, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, ON, Canada M5S 2C6, and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada M5S 3B2 ABSTRACT The impacts of ploidy level changes on plant physiology and ecology present interesting avenues of research, and many questions remain unanswered. -

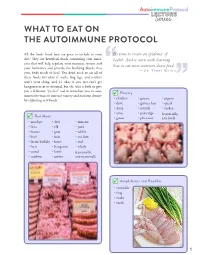

What to Eat on the Autoimmune Protocol

WHAT TO EAT ON THE AUTOIMMUNE PROTOCOL All the foods listed here are great to include in your It’s time to create an epidemic of - health. And it starts with learning ents that will help regulate your immune system and how to eat more nutrient-dense food. your hormones and provide the building blocks that your body needs to heal. You don’t need to eat all of these foods (it’s okay if snails, frog legs, and crickets aren’t your thing, and it’s okay if you just can’t get kangaroo meat or mizuna), but the idea is both to give Poultry innovative ways to increase variety and nutrient density • chicken • grouse • pigeon by exploring new foods. • dove • guinea hen • quail • duck • ostrich • turkey • emu • partridge (essentially, Red Meat • goose • pheasant any bird) • antelope • deer • mutton • bear • elk • pork • beaver • goat • rabbit • beef • hare • sea lion • • horse • seal • boar • kangaroo • whale • camel • lamb (essentially, • caribou • moose any mammal) Amphibians and Reptiles • crocodile • frog • snake • turtle 1 22 Fish* Shellfish • anchovy • gar • • abalone • limpet • scallop • Arctic char • haddock • salmon • clam • lobster • shrimp • Atlantic • hake • sardine • cockle • mussel • snail croaker • halibut • shad • conch • octopus • squid • barcheek • herring • shark • crab • oyster • whelk goby • John Dory • sheepshead • • periwinkle • bass • king • silverside • • prawn • bonito mackerel • smelt • bream • lamprey • snakehead • brill • ling • snapper • brisling • loach • sole • carp • mackerel • • • mahi mahi • tarpon • cod • marlin • tilapia • common dab • • • conger • minnow • trout • crappie • • tub gurnard • croaker • mullet • tuna • drum • pandora • turbot Other Seafood • eel • perch • walleye • anemone • sea squirt • fera • plaice • whiting • caviar/roe • sea urchin • • pollock • • *See page 387 for Selenium Health Benet Values. -

Production, Pomological and Nutraceutical Properties of Apricot

1 Production, pomological and nutraceutical properties of apricot Khaled Moustafa1* and Joanna Cross2 1Editor of ArabiXiv (arabixiv.org), Paris, France 2Nigde Omer Halisdemir University, Nigde, Turkey Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Apricot (Prunus sp.) is an important fruit crop worldwide. Despite recent advances in apricot research, much is still to be done to improve its productivity and environmental adaptability. The availability of wild apricot germplasms with economically interesting traits is a strong incentive to increase research panels toward improving its economic, environmental and nutritional characteristics. New technologies and genomic studies have generated a large amount of raw data that the mining and exploitation can help decrypt the biology of apricot and enhance its agronomic values. Here, we outline recent findings in relation to apricot production, pomological and nutraceutical properties. In particular, we retrace its origin from central Asia and the path it took to attain Europe and other production areas around the Mediterranean basin while locating it in the rosaceae family and referring to its genetic diversities and new attempts of classification. The production, nutritional, and nutraceutical importance of apricot are recapped in an easy readable and comparable way. We also highlight and discuss the effects of late frost damages on apricot production over different growth stages, from swollen buds to green fruits formation. Issues related to the length of production season and biotic and abiotic environmental challenges are also discussed with future perspective on how to lengthen the production season without compromising the fruit quality and productivity. Keywords Apricot kernel oil, plum pox virus, prunus armeniaca, spring frost, stone fruit, sharka. -

Wellesley College Botanic Gardens Edible Ecosystem Teaching Garden Plant List 2011-2015

Wellesley College Botanic Gardens Edible Ecosystem Teaching Garden Plant List 2011-2015 Genus species 'Cultivar' Common name # year habitat within garden planted planted Achillea 'Apfelblute' 'Apfelblute' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea 'Cassis' 'Cassis' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea 'Moonshine' 'Moonshine' yarrow 5 2013 Fruit Woodland, Asian Pear Achillea 'Oertel's Rose' 'Oertel's Rose' 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus yarrow Achillea 'Paprika' 'Paprika' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea 'Strawberry Seduction' 'Strawberry 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Seduction' yarrow Achillea 'Summer Wine' 'Summer Wine' 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus yarrow Achillea 'Terracotta' 'Terracotta' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea 'Velvet Red' 'Velvet Red' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea ageratifolia white tansy yarrow 43 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums Achillea millefolium yarrow 26 2011 Nut Grove Agastache foeniculum anise hyssop 4 2014 Fruit Thicket Ajuga reptans carpetweed 105 2011 Nut Grove Ajuga reptans 'Black Scallop' 'Black Scallop' 41 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums carpetweed Ajuga reptans 'Braunherz' or 'Braunherz' or 41 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums 'Bronze Heart' 'Bronze Heart' carpetweed Ajuga reptans 'Dixie Chip' 'Dixie Chip' 41 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums carpetweed Ajuga reptans 'Mahogany' 'Mahogany' 41 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums carpetweed Allium canadense wild garlic 4 2013 Fruit Woodland, Jujubes Allium canadense Canadian garlic 8 2015 Fruit Woodland Allium cepa aggregatum -

Phylogeny of Maleae (Rosaceae) Based on Multiple Chloroplast Regions: Implications to Genera Circumscription

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2018, Article ID 7627191, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7627191 Research Article Phylogeny of Maleae (Rosaceae) Based on Multiple Chloroplast Regions: Implications to Genera Circumscription Jiahui Sun ,1,2 Shuo Shi ,1,2,3 Jinlu Li,1,4 Jing Yu,1 Ling Wang,4 Xueying Yang,5 Ling Guo ,6 and Shiliang Zhou 1,2 1 State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China 2University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100043, China 3College of Life Science, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang 050024, China 4Te Department of Landscape Architecture, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China 5Key Laboratory of Forensic Genetics, Institute of Forensic Science, Ministry of Public Security, Beijing 100038, China 6Beijing Botanical Garden, Beijing 100093, China Correspondence should be addressed to Ling Guo; [email protected] and Shiliang Zhou; [email protected] Received 21 September 2017; Revised 11 December 2017; Accepted 2 January 2018; Published 19 March 2018 Academic Editor: Fengjie Sun Copyright © 2018 Jiahui Sun et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Maleae consists of economically and ecologically important plants. However, there are considerable disputes on generic circumscription due to the lack of a reliable phylogeny at generic level. In this study, molecular phylogeny of 35 generally accepted genera in Maleae is established using 15 chloroplast regions. Gillenia isthemostbasalcladeofMaleae,followedbyKageneckia + Lindleya, Vauquelinia, and a typical radiation clade, the core Maleae, suggesting that the proposal of four subtribes is reasonable. -

Phylogenetic Inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) Using Chloroplast Ndhf and Nuclear Ribosomal ITS Sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T

Journal of Systematics and Evolution 46 (3): 322–332 (2008) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1002.2008.08050 (formerly Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica) http://www.plantsystematics.com Phylogenetic inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) using chloroplast ndhF and nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T. BERGGREN 3Chung-Hee LEE 4Stefanie ICKERT-BOND 5Ting-Shuang YI 6Ki-Oug YOO 7Lei XIE 8Joey SHAW 9Dan POTTER 1(Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, MRC 166, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA) 2(Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA) 3(Korean National Arboretum, 51-7 Jikdongni Soheur-eup Pocheon-si Gyeonggi-do, 487-821, Korea) 4(UA Museum of the North and Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-6960, USA) 5(Key Laboratory of Plant Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650204, China) 6(Division of Life Sciences, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 200-701, Korea) 7(State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China) 8(Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, TN 37403-2598, USA) 9(Department of Plant Sciences, MS 2, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA) Abstract Sequences of the chloroplast ndhF gene and the nuclear ribosomal ITS regions are employed to recon- struct the phylogeny of Prunus (Rosaceae), and evaluate the classification schemes of this genus. The two data sets are congruent in that the genera Prunus s.l. and Maddenia form a monophyletic group, with Maddenia nested within Prunus. -

Edible Perennial Gardening and Landscaping”

“Edible Perennial Gardening and Landscaping” PLANTS NUTS: Chinese Chestnut (Castanea mollissima), Black Walnut (Juglans nigra), Heartnut (Juglans cordifolia), Buartnut (Juglans x bisbyi), Northern Pecan (Carya illinoiensis), Shellbark Hickory (Carya laciniosa), Hican (Carya illinoensis x ovata), Hardy Almond (Prunus amygdalus), Korean Nut Pine (Pinus koraiensis), Hazelnut (Corylus spp.) FRUITS: Mulberry (Morus nigra, M. rubra, M. alba), Chinese Mulberry (Cudrania tricuspidata), Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), Sweet Cherry (Prunus avium), Sour Cherry (Prunus cerasus), Nanking Cherry (Prunus tomentosa), Bush Cherry (Prunus japonica x P. jacquemontii), Quince (Cydonia oblonga), Apple Malus spp.), European Pear (Pyrus communis), Asian Pear (Pyrus pyrifolia), Shipova (Sorbus x Pyrus), Peach (Prunus persica), American Plum (Prunus americana), Beach Plum (Prunus maratima), Juneberry (Amelanchier spp.), Pawpaw (Asimina triloba), Hardy Orange (Poncirus trifoliata), Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas), Goumi (Elaeagnus multiflora), Goji (Lycium barbarum), Seaberry (Hippophae rhamnoides), Honeyberry (Lonicera kamchatika), Currants and Gooseberries (Ribes spp.), Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa), American Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.), Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon), Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), Raspberry (Rubus idaeus), Thornless Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus), Strawberries (Fragaria spp.), Hardy Kiwi (Actinidia arguta, A. kolomikta), Grape (Vitis spp.), Sandra Berry (Shisandra chinensis), Rugosa Rose (Rosa -

Basic Tree Information and Early Care Guide 4Th Edition by Kim Burnham, 2012 (Revised January 2015)

! Skagway Fruit and Nut Tree Planting Initiative Basic Tree Information and Early Care guide 4th Edition by Kim Burnham, 2012 (Revised January 2015) This is intended to be a very basic guide to selecting and planting fruit and nut trees. Following these instructions should help your tree(s) get off to a good start, but there is a lot more detailed information available elsewhere to help beginning fruit/nut tree growers care for their trees beyond the planting stage. A short list of additional resources is provided at the end of this guide, as are several tree nursery/suppliers. Why plant fruit or nut trees? The main reason to plant fruit trees, of course, is for the flavorful, nutritious fruit they will provide, for many years, once they become established. Essential nutrients (especially vitamin C) in fresh fruit can degrade quickly during the time fruit is transported from elsewhere, even when shipping conditions are optimal. Fresh, locally harvested fruit will not only taste better, but also may be more nutritious. Most nut trees are not cold- climate tolerant, but there are a couple of varieties (bush hazelnuts, dwarf Korean pine nut) that can tolerate cold winters, and could potentially provide a good source of protein. Any local food production will also help reduce Skagway’s carbon footprint and improve our food security. Fruit trees will also sequester small amounts of carbon while they add to the beauty of our “Garden City” with springtime blossoms and colorful fruit-ladened branches throughout the summer and into fall. Due to their longevity, many fruit and nut trees can also serve as heritage or memorial trees. -

Cornelian Cherry Dogwood

crops listed in many catalogs BUT ARE NOT READY FOR COMMERCIAL PRODUCTION CORNELIAN CHERRY DOGWOOD Cornelian cherry is not a true cherry, but a slow Cornelian cherries work perfectly in edible growing, globe-shaped, ornamental species of landscaping. The trees have a great form, along with dogwood (Cornus mas). The fruit is yellow to red tiny fragrant blossoms that open early in the spring. and oblong, similar to both the fruit of the flowering The fruits are even easy to harvest. Most people put dogwood of Eastern North America and the tiny a tarp under the tree when the fruit is ripe, shake the bunchberry plant in the northern forests. Cornelian tree and then gather the fruit off the ground to be cherries are the only dogwood species grown for used in jellies, juice and wine. fruit. Most Cornelian cherries are hardy through USDA Zone 4, and the tree does appear to be Note from Thaddeus: suitable for the southern third of Minnesota, with experimental plantings further north. I once visited the farm of a woman who had planted several of what she Cornelian cherries were primarily grown for their fruit in Eastern Europe from Austria to Turkey. Attempts to thought were true cherry trees but develop a market for the fruit in North America have were, in fact, Cornelian cherry trees. largely stuttered. Cornelian cherries have two traits After pointing out to the disappointed that make the trees difficult to grow profitably. The first is that there are few varieties available in the U.S. that woman that the slow growing trees in were selected for fruit quality. -

Molecular Phylogenetic Analyses Reveal a Close Evolutionary Relationship Between Podosphaera (Erysiphales: Erysiphaceae) and Its Rosaceous Hosts

Persoonia 24, 2010: 38–48 www.persoonia.org RESEARCH ARTICLE doi:10.3767/003158510X494596 Molecular phylogenetic analyses reveal a close evolutionary relationship between Podosphaera (Erysiphales: Erysiphaceae) and its rosaceous hosts S. Takamatsu1, S. Niinomi1, M. Harada1, M. Havrylenko 2 Key words Abstract Podosphaera is a genus of the powdery mildew fungi belonging to the tribe Cystotheceae of the Erysipha ceae. Among the host plants of Podosphaera, 86 % of hosts of the section Podosphaera and 57 % hosts of the 28S rDNA subsection Sphaerotheca belong to the Rosaceae. In order to reconstruct the phylogeny of Podosphaera and to evolution determine evolutionary relationships between Podosphaera and its host plants, we used 152 ITS sequences and ITS 69 28S rDNA sequences of Podosphaera for phylogenetic analyses. As a result, Podosphaera was divided into two molecular clock large clades: clade 1, consisting of the section Podosphaera on Prunus (P. tridactyla s.l.) and subsection Magnicel phylogeny lulatae; and clade 2, composed of the remaining member of section Podosphaera and subsection Sphaerotheca. powdery mildew fungi Because section Podosphaera takes a basal position in both clades, section Podosphaera may be ancestral in Rosaceae the genus Podosphaera, and the subsections Sphaerotheca and Magnicellulatae may have evolved from section Podosphaera independently. Podosphaera isolates from the respective subfamilies of Rosaceae each formed different groups in the trees, suggesting a close evolutionary relationship between Podosphaera spp. and their rosaceous hosts. However, tree topology comparison and molecular clock calibration did not support the possibility of co-speciation between Podosphaera and Rosaceae. Molecular phylogeny did not support species delimitation of P. aphanis, P. -

Using Chloroplast Trnl-Trnf Sequence Data

BIOLOGIJA. 2006. Nr. 1. P. 60–63 © Lietuvos mokslų akademija, 2006 60 R. Verbylaitė, B. Ford-Lloyd, J. Newbury © Lietuvos mokslų akademijos leidykla, 2006 The phylogeny of woody Maloideae (Rosaceae) using chloroplast trnL-trnF sequence data R. Verbylaitė, In this study, the most suitable DNA extraction protocols for Maloideae sub- family species were determined. Also, it was shown that the most suitable B. Ford-Lloyd, method to analyse phylogenetic data, such as observed in this study is the maximum parsimony method. J. Newbury The monophyletic origin of Maloideae subfamily including Vauquelinia and Kageneckia were confirmed. Close relationships between Crataegus and School of Biosciences, Mespilus were obtained. However, no intra-specific variation within the Ma- University of Birmingham, U. K. loideae genera according to trnL-trnF plastid region was observed, and the hypothesis of Mespilus canescens origin still needs more data to be confir- med or rejected. Key words: phylogeny, Maloideae, trnL-trnF, sequencing INTRODUCTION quelinia and Lindleya genera which have drupaceous or follicle fruits [3]. A recent phylogenetic analysis The Rosaceae family is subdivided into four subfami- in the subfamily Maloideae, based on ITS1, 5.8S lies. The subfamilies are: Spiraeoideae, Rosoideae, rDNA and ITS2, shows that the genus Mespilus is Amygdaloideae and Maloideae. To the family Rosace- nested within the Crataegus clade. This study also ae belong trees, shrubs and herbs. Leaves are usually suggests that endemic to Arkansas Mespilus canes- deciduous; some members of the family are evergre- cens could be of hybrid origin [4]. en. Rosaceae family plants have hermaphrodite flo- Though a huge amount of work has already been wers and are mostly entomophilous, pollinated by flies. -

Brozura Oskeruše.Indd

The Service Tree The Tree for a New NO Europe PRINT NO The Service Tree PRINT The Tree for a New Europe Mgr. et Mgr. Vít Hrdoušek Mgr. Zdeněk Špíšek prof. Dr. Ing. Boris Krška Ing. Jana Šedivá, Ph.D. Ing. Ladislav Bakay, Ph.D. NO PRINT Please pay 10 euro for use this PDF print. This money will be used for nice paper printing of this book. The Service Tree – the Tree for a New Europe Mgr. et Mgr. Vít Hrdoušek; Mgr. Zdeněk Špíšek; prof. Dr. Ing. Boris Krška; Ing. Jana Šedivá, Ph.D.; Ing. Ladislav Bakay, Ph.D. Published in 2014 by Petr Brázda – vydavatelství and MAS Strážnicko as part of the project “Rural Traditions in the Landscape II” ISBN: 978-80-87387-28-3 Index I. Introductory chapters 9 II. Service tree in history and art; Vít Hrdoušek, Zdeněk Špíšek, Ladislav Bakay 13 • II. 1. Service tree in historical sources • II. 2. Service tree in art • II. 3. Service tree in popular rendition • II. 4. Service tree and local names • II. 5. The history of the name “service tree” • II. 6. Service tree and the beginnings of pomology III. Service tree – description of the species; Vít Hrdoušek, Zdeněk Špíšek, Ladislav Bakay 39 NO• III. 1. Basic data on the species • III. 2. Morphology of the species • III. 3. Service tree variability IV. Service tree – species system and genetics; Zdeněk Špíšek, Vít Hrdoušek 53 • IV. 1. Service tree and related species • IV. 2. Genetics of the European service tree populations V. Service tree – ecology; Vít Hrdoušek, Zdeněk Špíšek, Ladislav Bakay 61 • V.