Brozura Oskeruše.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Potential of the Sorb (Sorbus Domestica L.) As a Minor Fruit Species in the Mediterranean Areas: Description and Quality Tr

Progress in Nutrition 2017; Vol. 19, Supplement 1: 41-48 DOI: 10.23751/pn.v19i1-S.5054 © Mattioli 1885 Original article The potential of the Sorb (Sorbus domestica L.) as a minor fruit species in the Mediterranean areas: description and quality traits of underutilized accessions Francesco Sottile1, Maria Beatrice Del Signore1, Nicole Roberta Giuggioli2, Cristiana Peano2 1Dipartimento Scienze Agrarie e Forestali, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy; 2Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie, Forestali e Alimentari, University of Torino, Grugliasco (TO) Italy - E-mail: [email protected] Summary. Biodiversity linked to fruit cultivation plays a key role in terms of the availability of quality products and nutraceutical compounds for the food industry. Thus underutilized species such as Sorbus domestica L. can be an important resource. The aim of this study was to evaluate 31 local accessions from different growing areas on the Island of Sicily and characterize the fruits according to the biometric-carpological features that constitute their qual- ity in order to understand the potential that this species may have not only regarding the recovery and preservation of genetic resources in the Mediterranean area but also the nutraceutical compounds it offers. The results from this preliminary study showed significant differences in quality between the considered accessions and suggested that these local varieties are a good source of total polyphenol compounds. Key words: biodiversity, Sorbus domestica L., minor fruits, quality, polyphenols Introduction acteristics both regarding size and qualitative parameters has inevitably caused a flattening of consumer tastes and Among the distribution ranges that fall within the indirectly the progressive loss of the plant patrimony that Mediterranean basin, Italy has always been an important was once the foundation of Italian fruit cultivation (1). -

Palace Tours − Luxury Tours Collection the Crimean Express (Northbound) the Crimean Express (Northbound)

Palace Tours − Luxury Tours Collection The Crimean Express (Northbound) The Crimean Express (Northbound) Embark on the brand−new Crimean Express journey from Kiev, which debuts in 2010! Spend two days in Kiev, one of Europe's oldest cities, before traveling by air to Yalta, where you will stay for two nights and enjoy visits to such places as Massandra Palace and the famous fairy−tale castle, the "Swallow's Nest." Travel on board the Golden Eagle private train for seven nights as you head north−west from Balaklava through Moldova, through Lviv, and Belarus' capital of Minsk. This fascinating tour continues as you are taken to several important destinations such as the Catherine Palace in Pushkin near St. Petersburg and the Red Square in Moscow, where your epic journey comes to an end. ITINERARY • Day 1 − Welcome to Ukraine Arrive at Simferopol Airport, where you are met and transferred to the luxury Hotel Oreanda in Yalta for a three−night stay. • Day 2 − Enjoy a full day of Yalta sightseeing Today there is a guided tour of Yalta including Chekhov's House and the Botanical Gardens, followed by lunch at the Swallow's Nest, a fairy−tale castle breathtakingly perched high above the sea. This restaurant is a world famous location and many world leaders have eaten here. In the afternoon we take a scenic cruise along the picturesque coastline before visiting the Massandra Palace and Imperial Winery, touring the cellars (they have bottles dating back to 1775 and many bottles from the Tsars personal collection). • Day 3 − Adventure in Yalta This morning we visit Alupka Palace which was built for Count Mikhail Vorontsov, former special envoy to the United Kingdom and friend of the Marlborough Family. -

WTO Documents Online

WORLD TRADE G/RO/45/Add.8/Rev.3 20 June 2002 ORGANIZATION (02-3429) Committee on Rules of Origin INTEGRATED NEGOTIATING TEXT FOR THE HARMONIZATION WORK PROGRAMME CHAPTERS 1-24 (AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS AND FISH) Note by the Secretariat Revision 1. At its meeting on 10 May 1996, the Committee on Rules of Origin (CRO) decided to establish an Integrated Negotiating Text (INT) for the Harmonization Work Programme. The first INT was circulated in document G/RO/W/13 (24 May 1996), and had been periodically updated (G/RO/W/13/Rev.1-3, G/RO/W/13/Rev.3/Add.1 and 2). A further consolidated INT was circulated in document G/RO/41(3 September 1999), and has also been periodically updated. 2. The attached document is the latest update of the negotiating text for Chapters 1-24 and reflects the progress made by the CRO in November 2001 and April 2002. G/RO/45/Add.8/Rev.3 Page 2 TERMINOLOGY GUIDE I. Rules presented at heading level: (a) If the rule is for the whole heading: CTH - change to this heading from any other heading (b) If the rule is for a split heading: CTHS - change to this split heading from any other split of this heading or from any other heading CTH - change to this split heading from any other heading (N.B. change from any other split of this heading is excluded.) II. Rules presented at subheading level: (a) If the rule is for the whole subheading: CTSH - change to this subheading from any other subheading or from any other heading CTH - change to this subheading from any other heading (N.B. -

Genome-Wide Characterization of Simple Sequence Repeats in Pyrus

Xue et al. BMC Genomics (2018) 19:473 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-4822-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Genome-wide characterization of simple sequence repeats in Pyrus bretschneideri and their application in an analysis of genetic diversity in pear Huabai Xue1,2†, Pujuan Zhang1†, Ting Shi1, Jian Yang2, Long Wang2, Suke Wang2, Yanli Su2, Huirong Zhang2, Yushan Qiao1* and Xiugen Li2* Abstract Background: Pear (Pyrus spp.) is an economically important temperate fruit tree worldwide. In the past decade, significant progress has been made in pear molecular genetics based on DNA research, but the number of molecular markers is still quite limited, which hardly satisfies the increasing needs of geneticists and breeders. Results: In this study, a total of 156,396 simple sequence repeat (SSR) loci were identified from a genome sequence of Pyrus bretschneideri ‘Dangshansuli’. A total of 101,694 pairs of SSR primers were designed from the SSR loci, and 80,415 of the SSR loci were successfully located on 17 linkage groups (LGs). A total of 534 primer pairs were synthesized and preliminarily screened in four pear cultivars, and of these, 332 primer pairs were selected as clear, stable, and polymorphic SSR markers. Eighteen polymorphic SSR markers were randomly selected from the 332 polymorphic SSR markers in order to perform a further analysis of the genetic diversity among 44 pear cultivars. The 14 European pears and their hybrid materials were clustered into one group (European pear group); 29 Asian pear cultivars were clustered into one group (Asian pear group); and the Zangli pear cultivar ‘Deqinli’ from Yunnan Province, China, was grouped in an independent group, which suggested that the cultivar ‘Deqinli’ is a distinct and valuable germplasm resource. -

SZENT ISTVÁN EGYETEM Kertészettudományi Kar

SZENT ISTVÁN EGYETEM Kertészettudományi Kar SORBUS FAJKELETKEZÉS TRIPARENTÁLIS HIBRIDIZÁCIÓVAL A KELET- ÉS DÉLKELET- EURÓPAI TÉRSÉGBEN (Nothosubgenus Triparens) Doktori (PhD) értekezés Németh Csaba BUDAPEST 2019 A doktori iskola megnevezése: Kertészettudományi Doktori Iskola tudományága: Növénytermesztési és kertészeti tudományok vezetője: Zámboriné Dr. Németh Éva egyetemi tanár, DSc Szent István Egyetem, Kertészettudományi Kar, Gyógy- és Aromanövények Tanszék Témavezető: Dr. Höhn Mária egyetemi docens, CSc Szent István Egyetem, Kertészettudományi Kar, Növénytani Tanszék és Soroksári Botanikus Kert A jelölt a Szent István Egyetem Doktori Szabályzatában előírt valamennyi feltételnek eleget tett, az értekezés műhelyvitájában elhangzott észrevételeket és javaslatokat az értekezés átdolgozásakor figyelembe vette, azért az értekezés védési eljárásra bocsátható. .................................................. .................................................. Az iskolavezető jóváhagyása A témavezető jóváhagyása 2 Édesanyám emlékének. 3 4 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK RÖVIDÍTÉSEK JEGYZÉKE .......................................................................................................... 7 1. BEVEZETÉS ÉS CÉLKITŰZÉS .................................................................................................. 9 2. IRODALMI ÁTTEKINTÉS ..................................................................................................... 11 2.1. A Sorbus nemzetség taxonómiai vonatkozásai .................................................................... -

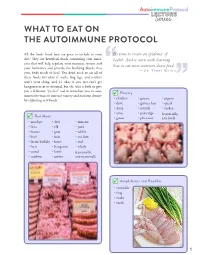

What to Eat on the Autoimmune Protocol

WHAT TO EAT ON THE AUTOIMMUNE PROTOCOL All the foods listed here are great to include in your It’s time to create an epidemic of - health. And it starts with learning ents that will help regulate your immune system and how to eat more nutrient-dense food. your hormones and provide the building blocks that your body needs to heal. You don’t need to eat all of these foods (it’s okay if snails, frog legs, and crickets aren’t your thing, and it’s okay if you just can’t get kangaroo meat or mizuna), but the idea is both to give Poultry innovative ways to increase variety and nutrient density • chicken • grouse • pigeon by exploring new foods. • dove • guinea hen • quail • duck • ostrich • turkey • emu • partridge (essentially, Red Meat • goose • pheasant any bird) • antelope • deer • mutton • bear • elk • pork • beaver • goat • rabbit • beef • hare • sea lion • • horse • seal • boar • kangaroo • whale • camel • lamb (essentially, • caribou • moose any mammal) Amphibians and Reptiles • crocodile • frog • snake • turtle 1 22 Fish* Shellfish • anchovy • gar • • abalone • limpet • scallop • Arctic char • haddock • salmon • clam • lobster • shrimp • Atlantic • hake • sardine • cockle • mussel • snail croaker • halibut • shad • conch • octopus • squid • barcheek • herring • shark • crab • oyster • whelk goby • John Dory • sheepshead • • periwinkle • bass • king • silverside • • prawn • bonito mackerel • smelt • bream • lamprey • snakehead • brill • ling • snapper • brisling • loach • sole • carp • mackerel • • • mahi mahi • tarpon • cod • marlin • tilapia • common dab • • • conger • minnow • trout • crappie • • tub gurnard • croaker • mullet • tuna • drum • pandora • turbot Other Seafood • eel • perch • walleye • anemone • sea squirt • fera • plaice • whiting • caviar/roe • sea urchin • • pollock • • *See page 387 for Selenium Health Benet Values. -

Noble Hardwoods Network

EUROPEAN FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES PROGRAMME (EUFORGEN) Noble Hardwoods Network Report of the second meeting 22-25 March 1997 Lourizan, Spain J. Turok, E. Collin, B. Demesure, G. Eriksson, J. Kleinschmit, M. Rusanen and R. Stephan, compilers ii NOBLE HARDWOODS NETWORK: SECOND MEETING The International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRl) is an autonomous international scientific organization, supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). IPGRl's mandate is to advance the conservation and use of plant genetic resources for the benefit of present and future generations. IPGRl's headquarters is based in Rome, Italy, with offices in another 14 countries worldwide. It operates through three programmes: (1) the Plant Genetic Resources Programme, (2) the CGIAR Genetic Resources Support Programme, and (3) the International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain (INIBAP). The international status of IPGRl is conferred under an Establishment Agreement which, by January 1998, had been signed and ratified by the Governments of Algeria, Australia, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, China, Congo, Costa Rica, Cote d'Ivoire, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, Guinea, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Malaysia, Mauritania, Morocco, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Slovak Republic, Sudan, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and Ukraine. Financial support for the Research Agenda of -

Wellesley College Botanic Gardens Edible Ecosystem Teaching Garden Plant List 2011-2015

Wellesley College Botanic Gardens Edible Ecosystem Teaching Garden Plant List 2011-2015 Genus species 'Cultivar' Common name # year habitat within garden planted planted Achillea 'Apfelblute' 'Apfelblute' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea 'Cassis' 'Cassis' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea 'Moonshine' 'Moonshine' yarrow 5 2013 Fruit Woodland, Asian Pear Achillea 'Oertel's Rose' 'Oertel's Rose' 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus yarrow Achillea 'Paprika' 'Paprika' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea 'Strawberry Seduction' 'Strawberry 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Seduction' yarrow Achillea 'Summer Wine' 'Summer Wine' 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus yarrow Achillea 'Terracotta' 'Terracotta' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea 'Velvet Red' 'Velvet Red' yarrow 7 2013 Fruit Thicket, Prunus Achillea ageratifolia white tansy yarrow 43 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums Achillea millefolium yarrow 26 2011 Nut Grove Agastache foeniculum anise hyssop 4 2014 Fruit Thicket Ajuga reptans carpetweed 105 2011 Nut Grove Ajuga reptans 'Black Scallop' 'Black Scallop' 41 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums carpetweed Ajuga reptans 'Braunherz' or 'Braunherz' or 41 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums 'Bronze Heart' 'Bronze Heart' carpetweed Ajuga reptans 'Dixie Chip' 'Dixie Chip' 41 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums carpetweed Ajuga reptans 'Mahogany' 'Mahogany' 41 2014 Fruit Thicket, Vacciniums carpetweed Allium canadense wild garlic 4 2013 Fruit Woodland, Jujubes Allium canadense Canadian garlic 8 2015 Fruit Woodland Allium cepa aggregatum -

Phylogeny of Maleae (Rosaceae) Based on Multiple Chloroplast Regions: Implications to Genera Circumscription

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2018, Article ID 7627191, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7627191 Research Article Phylogeny of Maleae (Rosaceae) Based on Multiple Chloroplast Regions: Implications to Genera Circumscription Jiahui Sun ,1,2 Shuo Shi ,1,2,3 Jinlu Li,1,4 Jing Yu,1 Ling Wang,4 Xueying Yang,5 Ling Guo ,6 and Shiliang Zhou 1,2 1 State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China 2University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100043, China 3College of Life Science, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang 050024, China 4Te Department of Landscape Architecture, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China 5Key Laboratory of Forensic Genetics, Institute of Forensic Science, Ministry of Public Security, Beijing 100038, China 6Beijing Botanical Garden, Beijing 100093, China Correspondence should be addressed to Ling Guo; [email protected] and Shiliang Zhou; [email protected] Received 21 September 2017; Revised 11 December 2017; Accepted 2 January 2018; Published 19 March 2018 Academic Editor: Fengjie Sun Copyright © 2018 Jiahui Sun et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Maleae consists of economically and ecologically important plants. However, there are considerable disputes on generic circumscription due to the lack of a reliable phylogeny at generic level. In this study, molecular phylogeny of 35 generally accepted genera in Maleae is established using 15 chloroplast regions. Gillenia isthemostbasalcladeofMaleae,followedbyKageneckia + Lindleya, Vauquelinia, and a typical radiation clade, the core Maleae, suggesting that the proposal of four subtribes is reasonable. -

Characterisation of Crude Pectin Extracted from Banana Peels.Pdf

THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND VETERINARY SCIENCES FACUL TY OF AGRICULTURE FINAL YEAR PROJECT CHARACTERISATION OF CRUDE PECTIN EXTRACTED FROM BANANA PEELS BY ACID METHOD. BY NYAGA M.WANGECI REG NO: A24/011112007 A project report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Degree of B.Sc. Food Science and technology. 2011 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this project is my work only with the guidance of my instructor and to my knowledge it has not been submitted to any other institution of higher learning. Signature: . Date: . Name: •..._..•.............................................. This project report has been submitted for examination with my approval to: Signature . Date •...••......................................... UNMRSllY OF NAIROBI DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SCIENCE, NUTRITION AND TECHNOLOGY 2 Acknowledgement I thank God the almighty for seeing me through my undergraduate more so this project. My acknowledgement goes to my supervisor, Prof J K Imungi of Food Technology and Nutrition Department for dedicating his time, sharing his knowledge, expertise and encouragement throughout my project work. My sincere appreciation also goes to the departments' technical staff; Mr.M'Thika, Ms.Rosemary and Ms. Jacinta who supported me fully and offered all the necessary assistance. lastly I thank The Department of Food Technology and Nutrition for funding this project and making a success. TABLE OF CONTENT Page CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 4-5 1.3: PROBLEM STATEMENT 6 1.4: JUSTIFICATION 6 1.5: OBJECTIVES 7 • Main and sub objectives 1.6: HYPOTHESIS 7 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW 7-10 CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY 11-12 CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Results 17-18 Discussion 19-20 CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION 21 CHAPTER SIX: RECOMMENDATION 21 REFERENCES 3 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.2: Background information 1.2.1: Pectin Pectin is a structural heteropolysaccharide contained in the primary cell walls ofterrestrial plants. -

Geomorphology of Neogene Volcanic Mountains in Hungary

Geogr. Fis. Dinam. Quat. 21 (1998), 79-85, 7 jigg. ANDRAs SZEKELY t ( ~'~) GEOMORPHOLOGY OF NEOGENE VOLCANIC MOUNTAINS IN HUNGARY ABSTRACT:SZEKELY A., Geomorphology 0/ Neogene volcanic moun INTRODUCTION tains in Hungary. (IT ISSN 0391-9838, 1998). This paper summarizes the achievements of detailed field work car Although mountains of low medium height only com ried out over more than 40 years, comp ares the results with earlier held prise about 20 per cent of the area of Hungary, some two views and present s the methods elabo rated for this research. These latter are : the study comp arison of landforms in relation to geological struct ure, thirds of th em are of Tertiary volcanic origin. Cons equent lith ology and bedding and a detailed analysis and interpretation of drain ly, volcanological and volcano-morphological research age pattern s. have been prominent topics of geological and geomorpho The analysis of drainage patterns provide valuable inform ation for logical investigations. Geologists have collected considera the recons truction of volcanic form s, since the main lines of the original (incip ient ) dr ainage network are preserved. D rainage patterns character ble information over th e last hundred years and produced istic of the various types of volcanoes are presented; the direct and indi many maps on the structure of volcanic mountains in Hun rect impacts of primary volcanic features and their governing function in gary. Th e first to present a comprehensive geomorphologi denudation are demonstrated. The origina l forms and sequence of era cal evaluation of all the volcanic mountains in the Car sion in the Terti ary volcanic areas are outline d with regard to the extent of post volcanic tectonic movements and their major impact on geomor pathian region was Cholnoky (1936), whose volcano phic evolution. -

Mountainous Crimea: a Frontier Zone of Ancient Civilization

Mountainous Crimea: A Frontier Zone of Ancient Civilization Natalia G. Novičenkova Mountainous Crimea, Taurica, was a region separated from the ancient cen- ters of the peninsula and the communication lines connecting Chersonesos and the Bosporan Kingdom. This region is not particularly well studied and therefore it has been impossible to trace its development in Antiquity, and to clarify its role in the history of ancient Crimea as a whole. The geographical conditions of the Mountainous Crimea determined that the ancient population of this area dwelled almost entirely on the main moun- tain range. From a modern point of view it seems unlikely that a mountain ridge could unite a population into a single ethnic group instead of splitting it into several distinct segments. Yet our evidence from Antiquity suggests the opposite. Thus, for example, Plinius the Elder wrote that the Scytho-Taurians inhabited the range (Plin. NH 4.85). This evidence has evoked bewilderment among scholars1 because this part of Crimea has the harshest weather condi- tions and is covered with snow from November to May almost every year. The main mountain range of Crimea is formed by a chain of plateaus situ- ated at about 1,000-1,500 m above sea level. Here an ancient road system was laid out uniting all the mountain passes into a single system of communica- tion.2 The plateaus with their alpine meadows served as excellent summer pastures. They were effectively protected against any threats from outside. The Taurians, who inhabited the mountain range, were not obliged to strug- gle for the steppe’s nomad territories or to drive their cattle for hundreds of kilometers.