Prescribed Burning Notebook Winter 2012 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Appendices

LAKE HOOD SEAPLANE BASE MASTER PLAN UPDATE Report Appendices September 2017 DOWL in conjunction with : RS&H, Southeast Strategies, and Solstice Advertising APPENDIX A Historical Photos of LHD THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK APPENDIX B Initial Survey Report THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK LAKE HOOD SEAPLANE BASE MASTER PLAN UPDATE User Survey Results April 2015 DOWL in conjunction with : RS&H, Southeast Strategies, and Solstice Advertising LAKE HOOD MASTER PLAN USER SURVEY RESULTS ANCHORAGE, ALASKA Prepared for: State of Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport P.O. Box 196960 Anchorage, Alaska 99519 Prepared by: DOWL 4041 B Street Anchorage, Alaska 99503 (907) 562-2000 AKSAS Number: 57737 April 2015 Lake Hood Master Plan Anchorage, Alaska User Survey Report April 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE ...............................................................................................1 WHO RESPONDED TO THE SURVEY .......................................................................................3 WHY DO YOU OPERATE FROM LHD .......................................................................................6 AIRCRAFT TYPES OPERATING OR POTENTIALLY OPERATING AT LHD .......................8 CAN/SHOULD LHD GROW .........................................................................................................9 INTEREST IN LEASING AND DEVELOPING AT LHD ..........................................................10 TYPE -

Early Winter 2004 on the Inside a “Look” Before and After the Skiing

SPECIAL ELECTION ISSUE FOR MEMBERS IN REGION 3, 4 & 7 Early Winter 2004 The Offi cial Publication of the Professional Ski Instructors of Amer i ca Eastern/Education Foundation A “Look” Before and After the Skiing Exams of 2003-04 by Peter Howard PSIA-E Chair, Alpine Education & Certifi cation Committee Over the years, progressions have been was a quality of performance that supersedes width, amount of wedge, when matching oc- used for teaching skiing and testing the com- the ability to get close in look to a certain curs, width of wedge, and the timing, duration petence of instructors. In the seventies, PSIA maneuver. But, perhaps because we couldn’t and intensity of movements. It is important brought the world the wonderful ski teaching quite fi gure out how to articulate the qual- that teachers can choose from, and demon- concept of being “Student- Centered”. The ity of performance we were looking for, we strate with, these tactical variations in order to practice of sticking with a narrow linear ap- continued in many cases to test for “one way provide an image that is tailored to the learning proach to learn to traverse, to snow plow, to do a wedge turn”. Sadly, the exam process needs of the students. When all of these tactical to stem, and to Christie was replaced by this was still somewhat maneuver-centered in an variations are supported by effi cient, modern, new concept. The bold and liberating idea of evolving Student-Centered era. and mechanically consistent movements, the student-centered teaching encouraged teach- So, what are the implications of these new marriage is complete. -

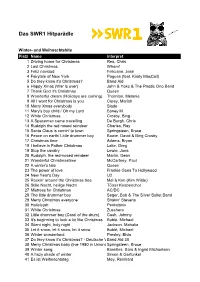

Das SWR1 Hitparädle

Das SWR1 Hitparädle Winter- und Weihnachtshits Platz Name Interpret 1 Driving home for Christmas Rea, Chris 2 Last Christmas Wham! 3 Feliz navidad Feliciano, José 4 Fairytale of New York Pogues (feat. Kirsty MacColl) 5 Do they know it's Christmas? Band Aid 6 Happy Xmas (War is over) John & Yoko & The Plastic Ono Band 7 Thank God it's Christmas Queen 8 Wonderful dream (Holidays are coming) Thornton, Melanie 9 All I want for Christmas is you Carey, Mariah 10 Merry Xmas everybody Slade 11 Mary's boy child / Oh my Lord Boney M. 12 White Christmas Crosby, Bing 13 A Spaceman came travelling De Burgh, Chris 14 Rudolph the red nosed reindeer Charles, Ray 15 Santa Claus is comin' to town Springsteen, Bruce 16 Peace on earth/ Little drummer boy Bowie, David & Bing Crosby 17 Christmas time Adams, Bryan 18 I believe in Father Christmas Lake, Greg 19 Stop the cavalry Lewie, Jona 20 Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer Martin, Dean 21 Wonderful Christmastime McCartney, Paul 22 A winter's tale Queen 23 The power of love Frankie Goes To Hollywood 24 New Year's Day U2 25 Rockin' around the Christmas tree Mel & Kim (Kim Wilde) 26 Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht Tölzer Knabenchor 27 Mistress for Christmas AC/DC 28 The little drummer boy Seger, Bob & The Silver Bullet Band 29 Merry Christmas everyone Shakin' Stevens 30 Hallelujah Pentatonix 31 White Christmas Zucchero 32 Little drummer boy (Carol of the drum) Cash, Johnny 33 It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas Bublé, Michael 34 Silent night, holy night Jackson, Mahalia 35 Let it snow, let it snow, let it -

The Winter Season December 1, 1990-February 28, 1991

STANDARDABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE REGIONALREPORTS Abbreviations used in placenames: THE In mostregions, place names given in •talictype are counties. WINTER Other abbreviations: Cr Creek SEASON Ft. Fort Hwy Highway I Island or Isle December1, 1990-February28, 1991 Is. Islands or Isles Jct. Junction km kilometer(s) AtlanticProvinces Region 244 TexasRegion 290 L Lake Ian A. McLaren GregW. Lasleyand Chuck Sexton mi mile(s) QuebecRegion 247 Mt. Mountain or Mount YvesAubry, Michel Gosselin, Idaho/ Mts. Mountains and Richard Yank Western Montana Region 294 N.F. National Forest ThomasH. Rogers 249 N.M. National Monument New England Blair Nikula MountainWest Region 296 N.P. National Park HughE. Kingety N.W.R. NationalWildlife Refuge Hudson-DelawareRegion 253 P P. Provincial Park WilliamJ. Boyle,Jr., SouthwestRegion 299 Pen. Peninsula Robert O. Paxton, and Arizona:David Stejskal Pt. Point (not Port) David A. Culter andGary H. Rosenberg New Mexico: R. River MiddleAtlantic Coast Region 258 Sartor O. Williams III Ref. Refuge HenryT. Armistead andJohn P. Hubbard Res. Reservoir(not Reservation) S P. State Park Sonthern Atlantic AlaskaRegion 394 262 W.M.A. WildlifeManagement Area CoastRegion T.G. Tobish,Jr. and (Fall 1990 Report) M.E. Isleib HarryE. LeGrand,Jr. Abbreviations used in the British Columbia/ names of birds: Florida Region 265 Yukon Region 306 Am. American JohnC. Ogden Chris Siddle Corn. Common 309 E. Eastern OntarioRegion 268 Oregon/WashingtonRegion Ron D. Weir (Fall 1990 Report) Eur. Europeanor Eurasian Bill Tweit and David Fix Mt. Mountain AppalachianRegion 272 N. Northern GeorgeA. Hall Oregon/WashingtonRegion 312 S. Southern Bill Tweit andJim Johnson W. Western Western Great Lakes Region 274 DavidJ. -

Substance-Exposed Infants: State Responses to the Problem

Substance-Exposed Infants: State Responses to the Problem www.samhsa.gov Substance Exposed Infants: State Responses to the Problem Acknowledgments This document was prepared by the National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare (NCSACW) under Contract No. 270‐027108 for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), both within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Nancy K. Young, Ph.D., developed the document with assistance from Sid Gardner, M.P.A.; Cathleen Otero, M.S.W., M.P.A.; Kim Dennis, M.P.A.; Rosa Chang, M.S.W.; Kari Earle, M.Ed., L.A.D.C.; and Sharon Amatetti, M.P.H. Sharon Amatetti, M.P.H., served as the Government Project Officer from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) and Irene Bocella, M.S.W., served as the Project Officer from Children’s Bureau. Disclaimer The views, opinions, and content of this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of SAMHSA or HHS. Resources listed in this document are not all‐inclusive and inclusion in the list does not constitute an endorsement by SAMHSA or HHS. Public Domain Notice All material appearing in this document is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without the permission of SAMHSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. However, this publication may not be reproduced or distributed for a fee without the specific, written authorization of the Office of Communications, SAMHSA, HHS. Electronic Access and Copies of Publication This publication may be downloaded or ordered at www.samhsa.gov/shin. -

The Connecticut College Literary Magazine Student Publications

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College The Connecticut College Literary Magazine Student Publications Spring 1973 The Connecticut College Literary Magazine Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/studentpubs_literarymag Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "The Connecticut College Literary Magazine" (1973). The Connecticut College Literary Magazine. 3. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/studentpubs_literarymag/3 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Connecticut College Literary Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Cover design: Allen Carroll The Connecticut College Literary Magazine Spring 1973 Co-Editors Susan Black Susan Urbanetti Associate Editors Jack Blossom Amy Bogert Ellen Ficklen Elizabeth Goldstein Katherine Williston Art Tod Gangler Litlepage Mark Wilson 1 Tod Gangler 6 Amy Bogert 9 Nancy Herschatter 12 Tod Gangler 13 David Katzenstein 15 Katherine Williston 17 Tom Hallett 20 Ted Gangler 21 Sarah Lipson 25 Tom Hallett 28 Katherine Wimston 30 Mark Heitner 32 Tod Gangler 33 Tod Gangler 35 Sarah Lipson 36 1 Writings Peter Carlson 4 Shadows M. Alexander Wilson 5 Early Morning, Late Winter Anita Perry 6 Chairs Ellen Ficklen 7 Susan Black 8 Afternoon Sleep Nikki Lloyd 11 river view Kevin Smith 12 Walking Nancy Cutting 13 Piefd Peter Carlson 14 You Hit an Artery Ellen Ficklen 15 Susan Black 16 Scene Jack Blossom 18 Jay B. Levin 19 Physics Lee Mills 22 open winter Tom Hallet 23 In Conversation M. -

The Winter Season December 1, 1973 -March 31, 1974

The Winter Season December 1, 1973 -March 31, 1974 NORTHEASTERN MARITIME REGION (EFA). Two more winter Greater Shearwaters in addi- tion to thoseof recentyears were a singlebird seenfrom /Davis W. Finch the "Princessof Acadia" in the Bay of Fundy Dec. 18 Mild conditions throughout New England and the (RDE) and another seen Feb. 18 in the same area as the Marltimes during late fall and early winter allowedmany just mentioned20,000 fulmars(VL). An interestingif in- speciesto remain far beyondtheir usualdeparture or kill- conclusivereport was that of a Great Cormorant so off dates, the phenomenonbeing perhapsmost apparent white-headedas to suggestthe Old World racesinensis, in Nova Scotia and coastal southernNew England. Wea- studied at Gloucester, Mass.. Feb. 16 (RAC, RJO et al.). ther later in the season returned to normal but nonethe- Single early winter Double-crestedCormorants were lessthere were a numberof casesof provenoverwinter- recorded on CBCs at Brier I., N.S., Dec. 20, N. Cha- ing by marginallyhardy species.Rough-legged Hawks. tham, Mass., Dec. 29, and New Bedford, Mass.. Dec. 30. AIcids, Snowy Owls. Bohemian Waxwings and N. Certainly the most surprisingbird on this year's CBCs Shrikes occurred in low or moderate numbers. and win- was a female Magnificent Frigatebird discoveredoff Sec- ter finch distribution was complex and interesting. ond Beach in Middletown, R.I.. Dec. 21 (LOG) and scrutinizedthe following day by other experiencedob- servers(TSG, RM). This was a fifth state record. and the latest ever in the Northeast, the only comparable record being a Nova Scotia specimentaken Dec. 5, 1932. HERONS--Indicative of the mild early winter were CBC totals of 149Great Blue Herons on Cape Cod Dec. -

The 1St Workshop on the Future of Winter Tourism (FWT2017) Collection of Papers

Organized and hosted by University of Lapland and Multidimensional Tourism Institute (MTI) The 1st Workshop on the Future of Winter Tourism (FWT2017) Rovaniemi, Finland, April 3 - April 5, 2017 Collection of Papers How to cite? Authors (2017). Title of presentation. Paper presented at the Workshop in the Future of Winter Tourism 2017 (FWT2017), held at the University of Lapland, April 3-5, Rovaniemi, Lapland, Finland. Unpublished collection of papers, pp. XX–XX. The copyright remains with the authors. This booklet is printed as part of the workshop material. CONTENTS SWOT analysis of winter travelling in the Alps: A Delphi Approach for 2030 3 Jannes Bayer, Hubert Siller, & Astrid Fehringer Arctic charity tourism 17 Daria Mishina Future of winter tourism in Turkey: Destination strategies for the Erzurum-Erzincan-Kars Winter Tourism Corridor (WTC) 36 Gurel Cetin & O. Cenk Demiroglu Skiing unlimited? Acceptance of resort extension by skiers in Tyrol/Austria 54 Ulrike Pröbstl-Haider, Nina Mostegl, & Wolfgang Haider Roles of internal stakeholders in development of a destination brand identity - case Levi ski resort 63 Raija Komppula, Päivi Pahkamaa, & Saila Saraniemi Shaping the future of winter tourism in rural Austria. Experiences from an applied research project. 64 Bruno Abegg & Robert Steiger The transformative capacity of Norwegian ski resorts in the face of climate change 73 Halvor Dannevig, Ida Marie Gildestad, Carlo Aall, Robert Steiger, & Daniel Scott Environmental impacts of winter sport resorts: Where do we go from now? 86 Carmen de Jong International tourism demand to Finnish Lapland in the early winter season 107 Martin Falk & Markku Vieru Future tourism related climate of ski resorts in Northern Finland 121 O. -

2019 Argentum

ARGENTUM The Art & Literary Magazine of Great Basin College 2019: A Modernistic View of the 1940 s Notes on 2019 Argentum At a 2018 summer wedding, a group of Argentum supporters were left unattended at a guest table during the reception, and the subject of the 2019 theme just happened to come up. From that discussion to this final version, the 1940s theme was set, as was the idea of prizes for the student winners. The most exciting aspect was the work and thought individuals put into their submissions, and we thank all those who submitted sincerely. The publication would not exist without you. As with any publication of this type, the work into making it happen doesn’t happen in a void. Special thanks are made to Angie de Braga, Dr. Josh Webster, Jennifer Bean, Patty Fox, and Ursula Stanton for their efforts in encouraging submissions and helping in every way possible from photographing submissions to reviewing material. We hope you enjoy this issue, and consider submitting to the 2020 issue of the publication. Our website is www.gbcnv.edu/argentum and we can be emailed at [email protected]. Dori Andrepont 2019 ARGENTUM EDITOR 1940 Beauty Contest Medium: Photography with background digital editing Susanne Reese Argentum 2019 Typography Notes Baskerville and Baskerville Italic date from 1750s, and variations were a particular favorite of hot typesetting systems of the twentieth century through the early 1960s. Futura was developed in 1927, and is known for its distinctive geometric shapes. was designed based on the work of calligrapher Ross Frederic George as it was depicted in the Advertising Script Speedball 1947 Textbook Manual. -

Saskatchewan Sheep Opportunity

Saskatchewan Sheep Opportunity Prepared by Saskatchewan Sheep Development Board 2213C Hanselman Court Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7L 6A8 Telephone: (306) 933-5200 Fax: (306) 933-7182 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.sksheep.com Sheep have been a part of Saskatchewan's economy for 200 years, with the first sheep arriving on the Canadian prairies in the early 1800's. While the sheep population has shifted with changing times in agriculture, lamb production remains an active part of Saskatchewan agriculture. Advantages to Raising Sheep The sheep industry lends itself well to a family enterprise. Sheep/lamb production can have a relatively low cost of entry with lower breeding stock costs and the ability to easily adapt existing livestock facili- ties to lamb production. Sheep adapt to various feed stuffs quickly. Sheep/lamb production can economically com- pliment other farming enterprises with environ- mental advantages to multi-species grazing. Noxious weeds and brush can be controlled using sheep in grazing programs. Six sheep can be sustained in the same area as one cow. picture provided by Farm and Food Care Saskatchewan Flock size can be increased quickly due to multiple births and short time to maturity. Producers have the potential to increase lambing percentages and lambs marketed per ewe. Sheep can be raised for meat production, wool or both depending on the breed. Sheep can be raised using a variety of production methods from grass-based to dry lot inten- sive . Sheep and the Environment Multispecies grazing can be used as a tool to accomplish specific grazing management goals. Using two species of animals to graze a pasture can diversify the type of forage utilized, the to- pographic location of preferred grazing areas, and may diversify income sources. -

Approved Christmas Music

1,000 Lights Javier Colon Beach Shag/Swing 2012 A Holly Jolly Christmas Alan Jackson Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Justin Bieber/Mariah Carey Beach Shag/Swing 2012 Christmas Canon Trans-Siberian Orchestra Entrance 2012 Christmas U2 Swing 2010 Christmas (Baby Please Come Home to Me) Mariah Carey Foxtrot (Medium) 2006 Christmas All Over Again Tom Petty Grand March 2005 Christmas Eve Justin Bieber Cha-Cha 2012 Fa La La Justin Bieber ft. Boyz II Men Foxtrot 2017 Gloria Van Morrison Foxtrot 1995 Hark the Herald Angels Sing Mariah Carey Listening 2005 Home This Christmas feat. The Band Perry Justin Bieber Background 2012 Honky Tonk Christmas Alan Jackson - Ultimate Christmas CD Line Dance 2006 Jesus What a Wonderful Child Mariah Carey Foxtrot (Medium) 2006 Jingle Bell Rock Randy Travis Shag/Swing 2005 Jingle Bell Rock Bobby Helms Swing 2010 Jingle Bell Rock Bobby Helms Beach Shag/Swing/Cha-Cha 2012 Joy to the World Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 Last Christmas Glee Cast Cha-Cha 2010 Last Christmas Taylor Swift Beach Shag/Swing/Cha-Cha 2012 Let It Snow, Let It Snow Martina McBride - Ultimate Christmas CD Cha Cha (Medium) 2006 Little Drummer Boy feat. Busta Rhymes Justin Bieber Line Dance 2012 Little Saint Nick Beach Boys Swing 2010 Merry Christmas Darling The Carpenters Foxtrot 2010 Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays N'Sync - Ultimate Christmas CD Cha Cha (Medium) 2006 Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays N'Sync Beach Shag/Swing/Cha-Cha 2012 My Only Wish (This Year) Britney Spears - Ultimate Christmas CD Foxtrot 2006 Now That's What I Call Christmas -The Signature Coll. -

Southern California Guidebook Sustainable and Fire-Safe Landscapes in the Wildland Urban Interface

Southern California Guidebook Sustainable and Fire-Safe Landscapes In The Wildland Urban Interface 1 2 S.A.F.E. LANDSCAPES Southern California Guidebook Sustainable and Fire-Safe Landscapes In The Wildland Urban Interface Sabrina L. Drill, Ph.D. Stephen L. Quarles, Ph.D. Valerie T. Borel University of California Cooperative Extension Drew Ready Jason Casanova Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers Watershed Council John Todd Los Angeles County Fire Department, Forestry Division Bill Nash Ventura County Fire Department University of California Cooperative Extension September 2009 3 THIS PROJECT WAS SUPPORTED BY THE RENEWABLE RESOURCES EXTENSION ACT, THE NATIONAL FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION, THE CALIFORNIA COMMUNITIES FOUNDATION, THE CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION, AND THE CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE. For questions or additional copies, please contact: UCCE - Los Angeles and Ventura Counties Natural Resources Program http://ucanr.org/safelandscapes phone #323-260-2267 4 CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................6 SAFE Landscapes..........................................................................................................................6 What is the Wildland Urban Interface?......................................................................................6 Sustainability..............................................................................................................................7 2. Climate, Fire, and