Major Warren Richard Colvin Wynne R.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flash Flood History Southeast and Coast Date and Sources

Flash flood history Southeast and coast Hydrometric Rivers Tributaries Towns and Cities area 40 Cray Darent Medway Eden, Teise, Beult, Bourne Stour Gt Stour, Little Stour Rother Dudwell 41 Cuckmere Ouse Berern Stream, Uck, Shell Brook Adur Rother Arun, Kird, Lod Lavant Ems 42 Meon, Hamble Itchen Arle Test Dever, Anton, Wallop Brook, Blackwater Lymington 101 Median Yar Date and Rainfall Description sources Sept 1271 <Canterbury>: A violent rain fell suddenly on Canterbury so that the greater part of the city was suddenly Doe (2016) inundated and there was such swelling of the water that the crypt of the church and the cloisters of the (Hamilton monastery were filled with water’. ‘Trees and hedges were overthrown whereby to proceed was not possible 1848-49) either to men or horses and many were imperilled by the force of waters flowing in the streets and in the houses of citizens’. 20 May 1739 <Cobham>, Surrey: The greatest storm of thunder rain and hail ever known with hail larger than the biggest Derby marbles. Incredible damage done. Mercury 8 Aug 1877 3 Jun 1747 <Midhurst> Sussex: In a thunderstorm a bridge on the <<Arun>> was carried away. Water was several feet deep Gentlemans in the church and churchyard. Sheep were drowned and two men were killed by lightning. Mag 12 Jun 1748 <Addington Place> Surrey: A thunderstorm with hail affected Surrey (and <Chelmsford> Essex and Warwick). Gentlemans Hail was 7 inches in circumference. Great damage was done to windows and gardens. Mag 10 Jun 1750 <Sittingbourne>, Kent: Thunderstorm killed 17 sheep in one place and several others. -

The Stately Homes of England

The Stately Homes of England Burghley House…Lincolnshire The Stately Homes of England, How beautiful they stand, To prove the Upper Classes, Have still the Upper Hand. Noel Coward Those comfortably padded lunatic asylums which are known, euphemistically, as the Stately Homes of England Virginia Woolf The development of the Stately home. What are the origins of the ‘Stately Home’ ? Who acquired the land to build them? Why build a formidable house? What purpose did they signify? Defining a Stately House or Home A large and impressive house that is occupied or was formerly occupied by an aristocratic family Kenwood House Hampstead Heath Upstairs, Downstairs…..A life of privilege and servitude There are over 500 Stages of evolution Fortified manor houses 11th -----15th C. Renaissance – 16th— early 17thC. Tudor Dynasty Jacobean –17th C. Stuart Dynasty Palladian –Mid 17th C. Stuart Dynasty Baroque Style—17th—18th C. Rococo Style or late Baroque --early to late 18thC. Neoclassical Style –Mid 18th C. Regency—Georgian Dynasty—Early 19th C. Victorian Gothic and Arts and Crafts – 19th—early 20th C. Modernism—20th C. This is our vision of a Stately Home Armour Weapons Library Robert Adam fireplaces, crystal chandeliers. But…… This is an ordinary terraced house Why are we fascinated By these mansions ? Is it the history and fabulous wealth?? Is it our voyeuristic tendencies ? Is it a sense of jealousy ,or a sense of belonging to a culture? Where did it all begin? A basic construction using willow and ash poles C. 450 A.D. A Celtic Chief’s Round House Wattle and daub walls, reed thatch More elaborate building materials and upper floor. -

The Rees and Carrington Extracts

THE REES AND CARRINGTON EXTRACTS CUMULATIVE INDEX – PEOPLE, PLACES AND THINGS – TO 1936 (INCLUSIVE) This index has been compiled straight from the text of the ‘Extracts’ (from January 1914 onwards, these include the ‘Rees Extracts’. – in the Index we have differentiated between them by using the same date conventions as in the text – black date for Carrington, Red date for Rees). In listing the movements, particularly of Kipling and his family, it is not always clear when who went where and when. Thus, “R. to Academy dinner” clearly refers to Kipling himself going alone to the dinner (as, indeed would have been the case – it was, in the 1890s, a men-only affair). But “Amusing dinner, Mr. Rhodes’s” probably refers to both of them going, and has been included as an entry under both Kipling, Caroline, and Kipling, Rudyard. There are many other similar events. And there are entries recording that, e.g., “Mrs. Kipling leaves”, without any indication of when she had come – but if it’s not in the ‘Extracts’ (though it may well have been in the original diaries) then, of course, it has not been possible to index it. The date given is the date of the diary entry which is not always the date of the event. We would also emphasise that the index does not necessarily give a complete record of who the Kiplings met, where they met them and what they did. It’s only an index of what remains of Carrie’s diaries, as recorded by Carrington and Rees. (We know a lot more about those people, places and things from, for example, Kipling’s published correspondence – but if they’re not in the diary extracts, then they won’t be found in this index.) Another factor is that both Carrington and Rees quite often mentions a name without further explanation or identification. -

The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) Author: John Morley Release Date: May 24, 2010, 2009 [Ebook 32510] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE (VOL 2 OF 3)*** The Life Of William Ewart Gladstone By John Morley In Three Volumes—Vol. II. (1859-1880) Toronto George N. Morang & Company, Limited Copyright, 1903 By The Macmillan Company Contents Book V. 1859-1868 . .2 Chapter I. The Italian Revolution. (1859-1860) . .2 Chapter II. The Great Budget. (1860-1861) . 21 Chapter III. Battle For Economy. (1860-1862) . 49 Chapter IV. The Spirit Of Gladstonian Finance. (1859- 1866) . 62 Chapter V. American Civil War. (1861-1863) . 79 Chapter VI. Death Of Friends—Days At Balmoral. (1861-1884) . 99 Chapter VII. Garibaldi—Denmark. (1864) . 121 Chapter VIII. Advance In Public Position And Other- wise. (1864) . 137 Chapter IX. Defeat At Oxford—Death Of Lord Palmer- ston—Parliamentary Leadership. (1865) . 156 Chapter X. Matters Ecclesiastical. (1864-1868) . 179 Chapter XI. Popular Estimates. (1868) . 192 Chapter XII. Letters. (1859-1868) . 203 Chapter XIII. Reform. (1866) . 223 Chapter XIV. The Struggle For Household Suffrage. (1867) . 250 Chapter XV. -

Lambeth Daily 28Th July 1998

The LambethDaily ISSUE No.8 TUESDAY JULY 28 1998 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE 1998 LAMBETH CONFERENCE TODAY’S KEY EVENTS What’s 7.00am Eucharist Mission top of Holy Land serves as 9.00am Coaches leave University campus for Lambeth Palace 12.00pm Lunch at Lambeth Palace agenda for cooking? 2.45pm Coaches depart Lambeth Palace for Buckingham Palace c. 6.00pm Coaches depart Buckingham Palace for Festival Pier College laboratory An avalanche of food c. 6.30pm Embarkation on Bateaux Mouche Japanese Church 6.45 - 9.30pm Boat trip along the Thames Page 3 Page 4 9.30pm Coaches depart Barrier Pier for University campus Page 3 Bishop Spong apologises to Africans by David Skidmore scientific theory. Bishop Spong has been in the n escalating rift between con- crosshairs of conservatives since last Aservative African bishops and November when he engaged in a Bishop John Spong (Newark, US) caustic exchange of letters with the appears headed for a truce. In an Archbishop of Canterbury over interview on Saturday Bishop homosexuality. In May he pub- Spong expressed regret for his ear- lished his latest book, Why Chris- Bishops on the run lier statements characterising tianity Must Change or Die, which African views on the Bible as questions the validity of a physical Bishops swapped purple for whites as teams captained by Bishop Michael “superstitious.” resurrection and other central prin- Photos: Anglican World/Jeff Sells Nazir-Ali (Rochester, England) and Bishop Arthur Malcolm (North Queens- Bishop Spong came under fire ciples of the creeds. land,Australia) met for a cricket match on Sunday afternoon. -

Photographic Collection 5-6-2013 the Photographic Collection Is Contained in Albums on the Library Room Shelves Against the External Wall

Photographic Collection 5-6-2013 The Photographic Collection is contained in Albums on the Library Room shelves against the external wall. County Parishes Title Country Date Range Topic Box Id Pub year Ambrotype Photograph c1854. Example. 1854 Ambrotype Photo PHC4901 1854 Cabinet Card c1870 to c1900 UK, c1866 USA, 1870-1900 Cabinet Card UK USA Photo PHC4903 Example. Crimean War, Christmas British officers Ukraine 1853-856 Ukraine Crimean War PHC6151 celebrate. Military Photo Cycling Club Outing. England 1898 Cycling Sport Photo PHC7503 1898 Harvest, Agricultural Labourer. England Harvest Agricultural PHC5901 Labourer Occupation Photo Holidays, Seaside. England 1920 Seaside Holidays Photo PHC4911 1920 Steeplechase. Victorian painting By Henry Alken. England Horse racing Sport Victorian PHC7501 Painting Alken Photo Manchester Manchester Mail Coach England 1837 Manchester Mail Coach PHC6901 1837 Occupation Transport Travel Photo Marple Photo taken in Marple of Ada Brownlow. Post 1898-1940 Post Card photos PHC4905 Card photos. Ruchterneed Highland Railway at Ruchterneed. Scotland 1906 Scotland Transport Train PHC6902 1906 Occupation Photo West Roxbury Jamica Pond, West Roxbury. Skating. England 1859 Skating Sport Jamica Pond PHC5403 1859 West Roxbury Photo Devon Paignton 14 June 2013 Page 1 of 9 The Photographic Collection is contained in Albums on the Library Room shelves against the external wall. County Parishes Title Country Date Range Topic Box Id Pub year Devon Paignton Paignton Pier, Devon. England 1879 Seaside Holidays Devon PHC5401 1879 Paignton Pier Photo Teignmouth Teignmouth. In late Victoria times. England 1880-1900 Seaside Holidays Devon PHC5402 Teignmouth Photo Essex Dagenham Summer Fun. Duchess of York at Dagenham, England Dagenham Essex Duchess PHC4912 Essex York Photo Kent Margate, Kent. -

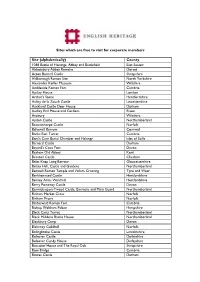

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Written Guide

Invasion coast A self-guided walk between Walmer and Deal in Kent Explore two towns shaped by the sea Discover how the East Kent coast has faced centuries of invasion Find out how this fragile landscape has evolved over the centuries Enjoy beautiful shingle beaches with diverse wildlife and spectacular views .discoveringbritain www .org ies of our land the stor scapes throug discovered h walks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed route maps and stopping points 8 Commentary 10 Further information 37 Credits 38 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2014 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: WW2 pillbox above Kingsdown beach © Grant Sibley 3 Invasion coast Explore a changing coastline between Walmer and Deal The East Kent coast between Walmer, Kingsdown and Deal has faced the threat of invasion for centuries. Its flat shores and proximity to Europe have attracted many overseas invaders from Julius Caesar’s Roman legions to Napoleon’s warships, from First World War bombers to Hitler’s planned invasion in 1940. But humans are not the only threat to this part of Britain’s coast. This coastline faces constant attack from the powerful forces of the North Sea. Wave and storm erosion along this coastline creates both threat and opportunity in a constantly shifting landscape. This walk explores the dynamic East Kent coast from the medieval village of Old Walmer to the twenty-first century seaside town of Deal. -

Walmer Design Statement (January 2006)

This document is dedicated to the memory of Derek W. Featherstone Chairman of the Walmer Design Statement Group April 2001 - August 2003 The Walmer Design Statement Group The Group was formed in April 2001, with the support of Walmer Parish Council, to prepare and publish a Design Statement for the Parish of Walmer. It is recognised that decisions made on planning matters within the parish must conform to current local authority planning policy. This Statement has been produced by the local community and is intended to influence the operation of the statutory planning system and give guidance for the design of all development in Walmer. Our objectives were: • to focus on the special character and design features in different parts of this large and diverse parish, • to set out Design Principles that could be applied appropriately, and • to give local residents an opportunity to influence future planning decisions in a constructive way. The document prepared had to represent their vision. The document has been the subject of a six-week public consultation exercise arranged by Dover District Council. Some alterations were made on the basis of comments received. Dover District Council has agreed to adopt the Walmer Design Statement as a material planning consideration in the assessment and determination of planning applications. ________ The Design Statement Group would like to express its appreciation to those listed Front Cover: Walmer Castle below for the time and expertise they gave to assist in the preparation of this Back Cover : Royal Marines Memorial Bandstand document. Sue Beer, Leslie Bulmer, David Collyer, English Heritage, Graham Hoskins, Arthur Leathern, Valerie LeVaillant, Gertrude Nunns, Richard Wells, Leon Williams, Fred Yardley © January 2006 All rights reserved. -

B Südengland - Die Vorschau 20

B Südengland - Die Vorschau 20 B Südengland - Hintergründe & Infos 24 Landschaft und Geographie 26 Wirtschaft und Politik 33 Klima und Reisezeit 28 Feste und andere kulturelle Flora, Fauna und Naturschutz 31 Highlights 36 Geschichte 38 Stonehenge und Caesar 38 Industrielle Revolution 51 Vom römischen Britannia zum Die Entdeckung der Küste 52 angel- sächsischen Königreich 39 Viktorianisches Zeitalter 54 1066 und die Folgen 42 Erster und Zweiter Weltkrieg 54 Schwarzer Tod und Rosenkriege 45 Zwischen Kriegsende und Die Häuser Tudor und Stuart 46 Millennium 55 Architektur 58 Normannisch (1066-1200) 58 Georgianisch (1714-1810) 59 Gotik (1200-1480) 58 Regency (1810-1830) 60 Tudor (1480-1600) 59 Viktorianisch (1830-1901) 60 Elisabethanisch (1558-1603) 59 20. Jahrhundert 60 Renaissance (1603-1714) 59 Literatur 60 Anreise 65 Mit dem Auto oder Motorrad 66 Mit dem Bus 73 Mit dem Flugzeug 70 Mitfahrzentralen/Trampen 73 Mit dem Zug 72 Unterwegs in Südengland _ 75 Mit dem eigenen Fahrzeug 75 Mit dem Fahrrad 79 Mit der Bahn 77 Taxi 80 Mit dem Bus 79 Übernachten 81 Hotels 82 Wohnungstausch 84 Bed & Breakfast (B & B) 83 Jugendherbergen 84 Ferienhäuser und -Wohnungen 84 Camping 85 http://d-nb.info/1038809436 Essen und Trinken 86 Freizeit, Sport und Strände 92 Angeln und Fischen 92 Heißluftballon 94 Badminton 92 Reiten 94 Birdwatching 93 Sauna 94 Cricket 93 Segeln und Surfen 94 Fußball 93 Strände und Baden 95 Golf 94 Tennis 95 Greyhoundracing 94 Wandern und Bergsteigen 96 Wissenswertes von A bis Z 97 Behinderte 97 Notruf 102 Diplomatische Vertretungen 97 Öffnungszeiten 102 Dokumente 97 Parken 103 Feiertage 97 Post 103 Geld 98 Radio und Fernsehen 103 Gesundheit 98 Rauchen 103 Gezeiten 99 Reisegepäckversicherung 104 Goethe-Institut 99 Schwule und Lesben 104 Haustiere 99 Sprachkurse 104 Information 100 Strom 105 Internet 100 Telefonieren 105 Landkarten 100 Trinkgeld 106 Maße und Gewichte 101 Uhrzeit 106 Museen und Zeitungen/Zeitschriften 106 Sehenswürdigkeiten 101 Zollbestimmungen 107 Südengland - London 108 London 110 City of London 136 Chelsea 159 Strand. -

2021 Civic Trust Awards & Pro Tem Regional Finalists

2021 CIVIC TRUST AWARDS & PRO TEM REGIONAL FINALISTS SCHEME NAME LA AREA REGION APPLICANT Mernda Rail Extension Melbourne Australia Grimshaw Borden Park Natural Swimming Pool (BPNSP) Edmonton Canada gh3* The Edge Edmonton Canada Dub Architects Shui Cultural Center Guizhou Province China West-line Studio Lille Langebro Copenhagen Denmark WilkinsonEyre Lea Fields Crematorium Lincoln East Midlands Haverstock Marmalade Lane Cambridge Eastern TOWN. & Mole Architects Student Services Centre University of Cambridge Cambridge Eastern Bennetts Associates City Park West, Chelmsford Chelmsford Eastern Pollard Thomas Edwards The Ark, Noah's Ark Children's Hospice Barnet Greater London Squire & Partners Crystal Palace Park Cafe Bromley Greater London Chris Dyson Architects LLP Granary Square Pavilion Camden Greater London Bell Phillips Architects Lincoln's Inn Great Hall and Library Camden Greater London MICA Architects The Standard, London Camden Greater London Orms Zayed Centre for Research into Rare Disease in Children Camden Greater London Stanton Williams 1 Finsbury Avenue City of London Greater London Allford Hall Monaghan Morris Illuminated River (Phase 1) City of London Greater London Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands The Post Building City of London Greater London Allford Hall Monaghan Morris Fairfield Halls Croydon Greater London MICA Architects The Officers' House, Royal Arsenal Greenwich Greater London Allford Hall Monaghan Morris The Plumstead Centre Greenwich Greater London Hawkins\Brown Build Up Hackney Hackney Greater London Build Up Foundation -

County Index, Hosts' Index, and Proposed Progresses

County Index of Visits by the Queen. Hosts’ Index: p.56. Proposed Progresses: p.68. Alleged and Traditional Visits: p.101. Mistaken visits: chronological list: p.103-106. County Index of Visits by the Queen. ‘Proposed progresses’: the section following this Index and Hosts’ Index. Other references are to the main Text. Counties are as they were in Elizabeth’s reign, disregarding later changes. (Knighted): knighted during the Queen’s visit. Proposed visits are in italics. Bedfordshire. Bletsoe: 1566 July 17/20: proposed: Oliver 1st Lord St John. 1578: ‘Proposed progresses’ (letter): Lord St John. Dunstable: 1562: ‘Proposed progresses’. At The Red Lion; owned by Edward Wyngate; inn-keeper Richard Amias: 1568 Aug 9-10; 1572 July 28-29. Eaton Socon, at Bushmead: 1566 July 17/20: proposed: William Gery. Holcot: 1575 June 16/17: dinner: Richard Chernock. Houghton Conquest, at Dame Ellensbury Park (royal): 1570 Aug 21/24: dinner, hunt. Luton: 1575 June 15: dinner: George Rotherham. Northill, via: 1566 July 16. Ridgmont, at Segenhoe: visits to Peter Grey. 1570 Aug 21/24: dinner, hunt. 1575 June 16/17: dinner. Toddington: visits to Henry Cheney. 1564 Sept 4-7 (knighted). 1570 Aug 16-25: now Sir Henry Cheney. (Became Lord Cheney in 1572). 1575 June 15-17: now Lord Cheney. Willington: 1566 July 16-20: John Gostwick. Woburn: owned by Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford. 1568: ‘Proposed progresses’. 1572 July 29-Aug 1. 1 Berkshire. Aldermaston: 1568 Sept 13-14: William Forster; died 1574. 1572: ‘Proposed progresses’. Visits to Humphrey Forster (son); died 1605. 1592 Aug 19-23 (knighted).