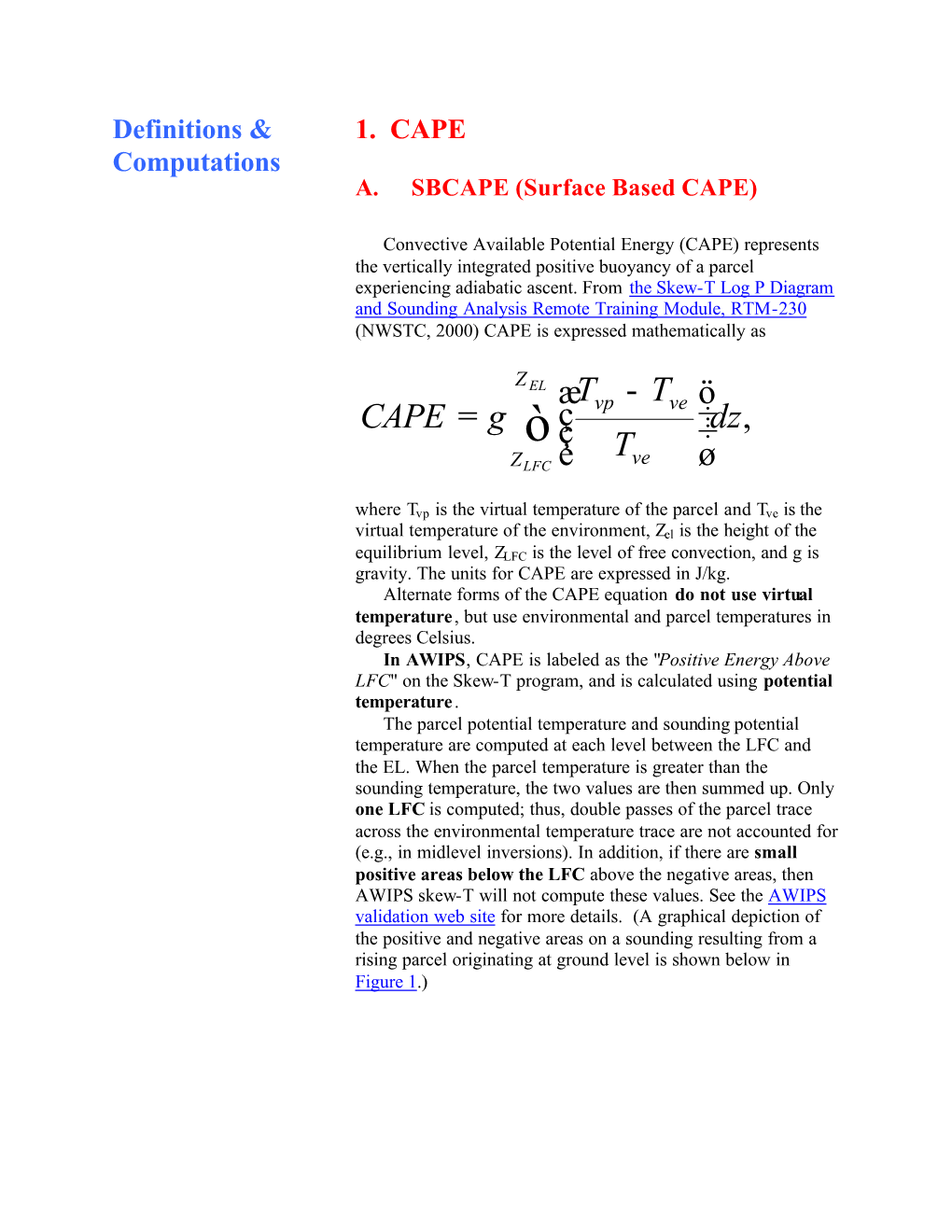

Dz T T T G CAPE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Local Large Hail Probability Equation for Columbia, Sc

EASTERN REGION TECHNICAL ATTACHMENT NO. 98-6 AUGUST, 1998 A LOCAL LARGE HAIL PROBABILITY EQUATION FOR COLUMBIA, SC Mark DeLisi NOAA/National Weather Service Forecast Office West Columbia, SC Editor’s Note: The author’s current affiliation is NWSFO Mt. Holly, NJ. 1. INTRODUCTION Skew-T/Hodograph Analysis and Research Program, or SHARP (Hart and Korotky Billet et al. (1997) derived a successful 1991). The dependent variable, hail diameter probability of large hail (diameter greater than or the absence of hail, was derived from or equal to 0.75 inch) equation as an aid in spotter reports for the CAE warning area from National Weather Service (NWS) severe May, 1995 through September, 1996. There thunderstorm warning operations. Hail of that were 136 cases used to develop the regression diameter or larger requires a severe equation. thunderstorm warning be issued by NWS offices. Shortly thereafter, a Weather The LPLH was verified using 69 spotter Surveillance Radar-1988 Doppler (WSR- reports from the period September, 1996 88D) radar probability of severe hail (POSH) through September, 1997. The POSH was became available for warning operations (Witt verified as well. Verification statistics et al. 1998). This study recreates the steps included the Brier score and the chi-square taken in Billet et al. (1997) to derive a local (32) statistic. probability of large hail equation (LPLH) for the Columbia, SC National Weather Service The goal of this study was to develop an Forecast Office (CAE) warning area, and it objective method to estimate the probability assesses the utility of the LPLH relative to the of large hail for use in forecast operations. -

Use Style: Paper Title

Environmental Conditions Producing Thunderstorms with Anomalous Vertical Polarity of Charge Structure Donald R. MacGorman Alexander J. Eddy NOAA/Nat’l Severe Storms Laboratory & Cooperative Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies Studies Affiliation/ Univ. of Oklahoma and NOAA/OAR Norman, Oklahoma, USA Norman, Oklahoma, USA [email protected] Earle Williams Cameron R. Homeyer Massachusetts Insitute of Technology School of Meteorology, Univ. of Oklhaoma Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA Norman, Oklahoma, USA Abstract—+CG flashes typically comprise an unusually large Tessendorf et al. 2007, Weiss et al. 2008, Fleenor et al. 2009, fraction of CG activity in thunderstorms with anomalous vertical Emersic et al. 2011; DiGangi et al. 2016). Furthermore, charge structure. We analyzed more than a decade of NLDN previous studies have suggested that CG activity tends to be data on a 15 km x 15 km x 15 min grid spanning the contiguous delayed tens of minutes longer in these anomalous storms than United States, to identify storm cells in which +CG flashes in most storms elsewhere (MacGorman et al. 2011). constituted a large fraction of CG activity, as a proxy for thunderstorms with anomalous vertical charge structure, and For this study, we analyzed more than a decade of CG data storm cells with very low percentages of +CG lightning, as a from the National Lightning Detection Network throughout the proxy for thunderstorms with normal-polarity distributions. In contiguous United States to identify storm cells in which +CG each of seven regions, we used North American Regional flashes constituted a large fraction of CG activity, as a proxy Reanalysis data to compare the environments of anomalous for storms with anomalous vertical charge structure. -

Chapter 8 Atmospheric Statics and Stability

Chapter 8 Atmospheric Statics and Stability 1. The Hydrostatic Equation • HydroSTATIC – dw/dt = 0! • Represents the balance between the upward directed pressure gradient force and downward directed gravity. ρ = const within this slab dp A=1 dz Force balance p-dp ρ p g d z upward pressure gradient force = downward force by gravity • p=F/A. A=1 m2, so upward force on bottom of slab is p, downward force on top is p-dp, so net upward force is dp. • Weight due to gravity is F=mg=ρgdz • Force balance: dp/dz = -ρg 2. Geopotential • Like potential energy. It is the work done on a parcel of air (per unit mass, to raise that parcel from the ground to a height z. • dφ ≡ gdz, so • Geopotential height – used as vertical coordinate often in synoptic meteorology. ≡ φ( 2 • Z z)/go (where go is 9.81 m/s ). • Note: Since gravity decreases with height (only slightly in troposphere), geopotential height Z will be a little less than actual height z. 3. The Hypsometric Equation and Thickness • Combining the equation for geopotential height with the ρ hydrostatic equation and the equation of state p = Rd Tv, • Integrating and assuming a mean virtual temp (so it can be a constant and pulled outside the integral), we get the hypsometric equation: • For a given mean virtual temperature, this equation allows for calculation of the thickness of the layer between 2 given pressure levels. • For two given pressure levels, the thickness is lower when the virtual temperature is lower, (ie., denser air). • Since thickness is readily calculated from radiosonde measurements, it provides an excellent forecasting tool. -

Comparison Between Observed Convective Cloud-Base Heights and Lifting Condensation Level for Two Different Lifted Parcels

AUGUST 2002 NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE 885 Comparison between Observed Convective Cloud-Base Heights and Lifting Condensation Level for Two Different Lifted Parcels JEFFREY P. C RAVEN AND RYAN E. JEWELL NOAA/NWS/Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma HAROLD E. BROOKS NOAA/National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma 6 January 2002 and 16 April 2002 ABSTRACT Approximately 400 Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS) observations of convective cloud-base heights at 2300 UTC were collected from April through August of 2001. These observations were compared with lifting condensation level (LCL) heights above ground level determined by 0000 UTC rawinsonde soundings from collocated upper-air sites. The LCL heights were calculated using both surface-based parcels (SBLCL) and mean-layer parcels (MLLCLÐusing mean temperature and dewpoint in lowest 100 hPa). The results show that the mean error for the MLLCL heights was substantially less than for SBLCL heights, with SBLCL heights consistently lower than observed cloud bases. These ®ndings suggest that the mean-layer parcel is likely more representative of the actual parcel associated with convective cloud development, which has implications for calculations of thermodynamic parameters such as convective available potential energy (CAPE) and convective inhibition. In addition, the median value of surface-based CAPE (SBCAPE) was more than 2 times that of the mean-layer CAPE (MLCAPE). Thus, caution is advised when considering surface-based thermodynamic indices, despite the assumed presence of a well-mixed afternoon boundary layer. 1. Introduction dry-adiabatic temperature pro®le (constant potential The lifting condensation level (LCL) has long been temperature in the mixed layer) and a moisture pro®le used to estimate boundary layer cloud heights (e.g., described by a constant mixing ratio. -

How Appropriate They Are/Will Be Using Future Satellite Data Sources?

Different Convective Indices - - - How appropriate they are/will be using future satellite data sources? Ralph A. Petersen1 1 Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS), University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA Will additional input from Steve Weiss, NOAA/NWS/Storm Prediction Center ✓ Increasing the Utility / Value of real-time Satellite Sounder Products to fill gaps in their short-range forecasting processes Creating Temperature/Moisture Soundings from Infra-Red (IR) Satellite Observations A Conceptual Tutorial All level of the atmosphere is continually emit radiation toward space. Satellites observe the net amount reaching space. • Conceptually, we can think about the atmosphere being made up of many thin layers Start from the bottom and work up. 1 – The greatest amount of radiation is emitted from the earth’s surface 4 - Remember, Stefan’s Law: Emission ~ σTSfc 2 – Molecules of various gases in the lowest layer of the atmosphere absorb some of the radiation and then reemit it upward to space and back downward to the earth’s surface - Major absorbers are CO2 and H2O 4 - Emission again ~ σT , but TAtmosphere<TSfc - Amount of radiation decreases with altitude Creating Temperature/Moisture Soundings from Infra-Red (IR) Satellite Observations A Conceptual Tutorial All level of the atmosphere is continually emit radiation toward space. Satellites observe the net amount reaching space. • Conceptually, we can think about the atmosphere being made up of many thin layers Start from the bottom and work -

MSE3 Ch14 Thunderstorms

Chapter 14 Copyright © 2011, 2015 by Roland Stull. Meteorology for Scientists and Engineers, 3rd Ed. thunderstorms Contents Thunderstorms are among the most violent and difficult-to-predict weath- Thunderstorm Characteristics 481 er elements. Yet, thunderstorms can be Appearance 482 14 studied. They can be probed with radar and air- Clouds Associated with Thunderstorms 482 craft, and simulated in a laboratory or by computer. Cells & Evolution 484 They form in the air, and must obey the laws of fluid Thunderstorm Types & Organization 486 mechanics and thermodynamics. Basic Storms 486 Thunderstorms are also beautiful and majestic. Mesoscale Convective Systems 488 Supercell Thunderstorms 492 In thunderstorms, aesthetics and science merge, making them fascinating to study and chase. Thunderstorm Formation 496 Convective Conditions 496 Thunderstorm characteristics, formation, and Key Altitudes 496 forecasting are covered in this chapter. The next chapter covers thunderstorm hazards including High Humidity in the ABL 499 hail, gust fronts, lightning, and tornadoes. Instability, CAPE & Updrafts 503 CAPE 503 Updraft Velocity 508 Wind Shear in the Environment 509 Hodograph Basics 510 thunderstorm CharaCteristiCs Using Hodographs 514 Shear Across a Single Layer 514 Thunderstorms are convective clouds Mean Wind Shear Vector 514 with large vertical extent, often with tops near the Total Shear Magnitude 515 tropopause and bases near the top of the boundary Mean Environmental Wind (Normal Storm Mo- layer. Their official name is cumulonimbus (see tion) 516 the Clouds Chapter), for which the abbreviation is Supercell Storm Motion 518 Bulk Richardson Number 521 Cb. On weather maps the symbol represents thunderstorms, with a dot •, asterisk , or triangle Triggering vs. Convective Inhibition 522 * ∆ drawn just above the top of the symbol to indicate Convective Inhibition (CIN) 523 Trigger Mechanisms 525 rain, snow, or hail, respectively. -

Potential Vorticity

POTENTIAL VORTICITY Roger K. Smith March 3, 2003 Contents 1 Potential Vorticity Thinking - How might it help the fore- caster? 2 1.1Introduction............................ 2 1.2WhatisPV-thinking?...................... 4 1.3Examplesof‘PV-thinking’.................... 7 1.3.1 A thought-experiment for understanding tropical cy- clonemotion........................ 7 1.3.2 Kelvin-Helmholtz shear instability . ......... 9 1.3.3 Rossby wave propagation in a β-planechannel..... 12 1.4ThestructureofEPVintheatmosphere............ 13 1.4.1 Isentropicpotentialvorticitymaps........... 14 1.4.2 The vertical structure of upper-air PV anomalies . 18 2 A Potential Vorticity view of cyclogenesis 21 2.1PreliminaryIdeas......................... 21 2.2SurfacelayersofPV....................... 21 2.3Potentialvorticitygradientwaves................ 23 2.4 Baroclinic Instability . .................... 28 2.5 Applications to understanding cyclogenesis . ......... 30 3 Invertibility, iso-PV charts, diabatic and frictional effects. 33 3.1 Invertibility of EPV ........................ 33 3.2Iso-PVcharts........................... 33 3.3Diabaticandfrictionaleffects.................. 34 3.4Theeffectsofdiabaticheatingoncyclogenesis......... 36 3.5Thedemiseofcutofflowsandblockinganticyclones...... 36 3.6AdvantageofPVanalysisofcutofflows............. 37 3.7ThePVstructureoftropicalcyclones.............. 37 1 Chapter 1 Potential Vorticity Thinking - How might it help the forecaster? 1.1 Introduction A review paper on the applications of Potential Vorticity (PV-) concepts by Brian -

Atmospheric Instability Parameters Derived from Msg Seviri Observations

P3.33 ATMOSPHERIC INSTABILITY PARAMETERS DERIVED FROM MSG SEVIRI OBSERVATIONS Marianne König*, Stephen Tjemkes, Jochen Kerkmann EUMETSAT, Darmstadt, Germany 1. INTRODUCTION K-Index: Convective systems can develop in a thermo- (Tobs(850)–Tobs(500)) + TDobs(850) – (Tobs(700)–TDobs(700)) dynamically unstable atmosphere. Such systems may quickly reach high altitudes and can cause severe Lifted Index: storms. Meteorologists are thus especially interested to Tobs - Tlifted from surface at 500 hPa identify such storm potentials when the respective system is still in a preconvective state. A number of Maximum buoyancy: obs(max betw. surface and 850) obs(min betw. 700 and 300) instability indices have been defined to describe such Qe - Qe situations. Traditionally, these indices are taken from temperature and humidity soundings by radiosondes. As (T is temperature, TD is dewpoint temperature, and Qe radiosondes are only of very limited temporal and is equivalent potential temperature, numbers 850, 700, spatial resolution there is a demand for satellite-derived 300 indicate respective hPa level in the atmosphere) indices. The Meteorological Product Extraction Facility (MPEF) for the new European Meteosat Second and the precipitable water content as additionally Generation (MSG) satellite envisages the operational derived parameter. derivation of a number of instability indices from the brightness temperatures measured by certain SEVIRI 3. DESCRIPTION OF ALGORITHMS channels (Spinning Enhanced Visible and Infrared Imager, the radiometer onboard MSG). The traditional 3.1 The Physical Retrieval physical approach to this kind of retrieval problem is to infer the atmospheric profile via a constrained inversion An iterative solution to the inversion equation (e.g. and compute the indices then directly from the obtained Ma et al. -

Basic Features on a Skew-T Chart

Skew-T Analysis and Stability Indices to Diagnose Severe Thunderstorm Potential Mteor 417 – Iowa State University – Week 6 Bill Gallus Basic features on a skew-T chart Moist adiabat isotherm Mixing ratio line isobar Dry adiabat Parameters that can be determined on a skew-T chart • Mixing ratio (w)– read from dew point curve • Saturation mixing ratio (ws) – read from Temp curve • Rel. Humidity = w/ws More parameters • Vapor pressure (e) – go from dew point up an isotherm to 622mb and read off the mixing ratio (but treat it as mb instead of g/kg) • Saturation vapor pressure (es)– same as above but start at temperature instead of dew point • Wet Bulb Temperature (Tw)– lift air to saturation (take temperature up dry adiabat and dew point up mixing ratio line until they meet). Then go down a moist adiabat to the starting level • Wet Bulb Potential Temperature (θw) – same as Wet Bulb Temperature but keep descending moist adiabat to 1000 mb More parameters • Potential Temperature (θ) – go down dry adiabat from temperature to 1000 mb • Equivalent Temperature (TE) – lift air to saturation and keep lifting to upper troposphere where dry adiabats and moist adiabats become parallel. Then descend a dry adiabat to the starting level. • Equivalent Potential Temperature (θE) – same as above but descend to 1000 mb. Meaning of some parameters • Wet bulb temperature is the temperature air would be cooled to if if water was evaporated into it. Can be useful for forecasting rain/snow changeover if air is dry when precipitation starts as rain. Can also give -

P7.1 a Comparative Verification of Two “Cap” Indices in Forecasting Thunderstorms

P7.1 A COMPARATIVE VERIFICATION OF TWO “CAP” INDICES IN FORECASTING THUNDERSTORMS David L. Keller Headquarters Air Force Weather Agency, Offutt AFB, Nebraska 1. INTRODUCTION layer parcels are then sufficiently buoyant to rise to the Level of Free Convection (LFC), resulting in convection The forecasting of non-severe and severe and possibly thunderstorms. In many cases dynamic thunderstorms in the continental United States forcing such as low-level convergence, low-level warm (CONUS) for military customers is the responsibility of advection, or positive vorticity advection provide the Air Force Weather Agency (AFWA) CONUS Severe additional force to mechanically lift boundary layer Weather Operations (CONUS OPS), and of the Storm parcels through the inversion. Prediction Center (SPC) for the civilian government. In the morning hours, one of the biggest Severe weather is defined by both of these challenges in severe weather forecasting is to organizations as the occurrence of a tornado, hail determine not only if, but also where the cap will break larger than 19 mm, wind speed of 25.7 m/s, or wind later in the day. Model forecasts help determine future damage. These agencies produce ‘outlooks’ denoting soundings. Based on the model data, severe storm areas where non-severe and severe thunderstorms are indices can be calculated that help measure the expected. Outlooks are issued for the current day, for predicted dynamic forcing, instability, and the future ‘tomorrow’ and the day following. The ‘day 1’ forecast state of the capping inversion. is normally issued 3 to 5 times per day, the ‘day 2’ and One measure of the cap is the Convective ‘day 3’ forecasts less frequently. -

ESCI 241 – Meteorology Lesson 8 - Thermodynamic Diagrams Dr

ESCI 241 – Meteorology Lesson 8 - Thermodynamic Diagrams Dr. DeCaria References: The Use of the Skew T, Log P Diagram in Analysis And Forecasting, AWS/TR-79/006, U.S. Air Force, Revised 1979 An Introduction to Theoretical Meteorology, Hess GENERAL Thermodynamic diagrams are used to display lines representing the major processes that air can undergo (adiabatic, isobaric, isothermal, pseudo- adiabatic). The simplest thermodynamic diagram would be to use pressure as the y-axis and temperature as the x-axis. The ideal thermodynamic diagram has three important properties The area enclosed by a cyclic process on the diagram is proportional to the work done in that process As many of the process lines as possible be straight (or nearly straight) A large angle (90 ideally) between adiabats and isotherms There are several different types of thermodynamic diagrams, all meeting the above criteria to a greater or lesser extent. They are the Stuve diagram, the emagram, the tephigram, and the skew-T/log p diagram The most commonly used diagram in the U.S. is the Skew-T/log p diagram. The Skew-T diagram is the diagram of choice among the National Weather Service and the military. The Stuve diagram is also sometimes used, though area on a Stuve diagram is not proportional to work. SKEW-T/LOG P DIAGRAM Uses natural log of pressure as the vertical coordinate Since pressure decreases exponentially with height, this means that the vertical coordinate roughly represents altitude. Isotherms, instead of being vertical, are slanted upward to the right. Adiabats are lines that are semi-straight, and slope upward to the left. -

Storm Spotting – Solidifying the Basics PROFESSOR PAUL SIRVATKA COLLEGE of DUPAGE METEOROLOGY Focus on Anticipating and Spotting

Storm Spotting – Solidifying the Basics PROFESSOR PAUL SIRVATKA COLLEGE OF DUPAGE METEOROLOGY HTTP://WEATHER.COD.EDU Focus on Anticipating and Spotting • What do you look for? • What will you actually see? • Can you identify what is going on with the storm? Is Gilbert married? Hmmmmm….rumor has it….. Its all about the updraft! Not that easy! • Various types of storms and storm structures. • A tornado is a “big sucky • Obscuration of important thing” and underneath the features make spotting updraft is where it forms. difficult. • So find the updraft! • The closer you are to a storm the more difficult it becomes to make these identifications. Conceptual models Reality is much harder. Basic Conceptual Model Sometimes its easy! North Central Illinois, 2-28-17 (Courtesy of Matt Piechota) Other times, not so much. Reality usually is far more complicated than our perfect pictures Rain Free Base Dusty Outflow More like reality SCUD Scattered Cumulus Under Deck Sigh...wall clouds! • Wall clouds help spotters identify where the updraft of a storm is • Wall clouds may or may not be present with tornadic storms • Wall clouds may be seen with any storm with an updraft • Wall clouds may or may not be rotating • Wall clouds may or may not result in tornadoes • Wall clouds should not be reported unless there is strong and easily observable rotation noted • When a clear slot is observed, a well written or transmitted report should say as much Characteristics of a Tornadic Wall Cloud • Surface-based inflow • Rapid vertical motion (scud-sucking) • Persistent • Persistent rotation Clear Slot • The key, however, is the development of a clear slot Prof.