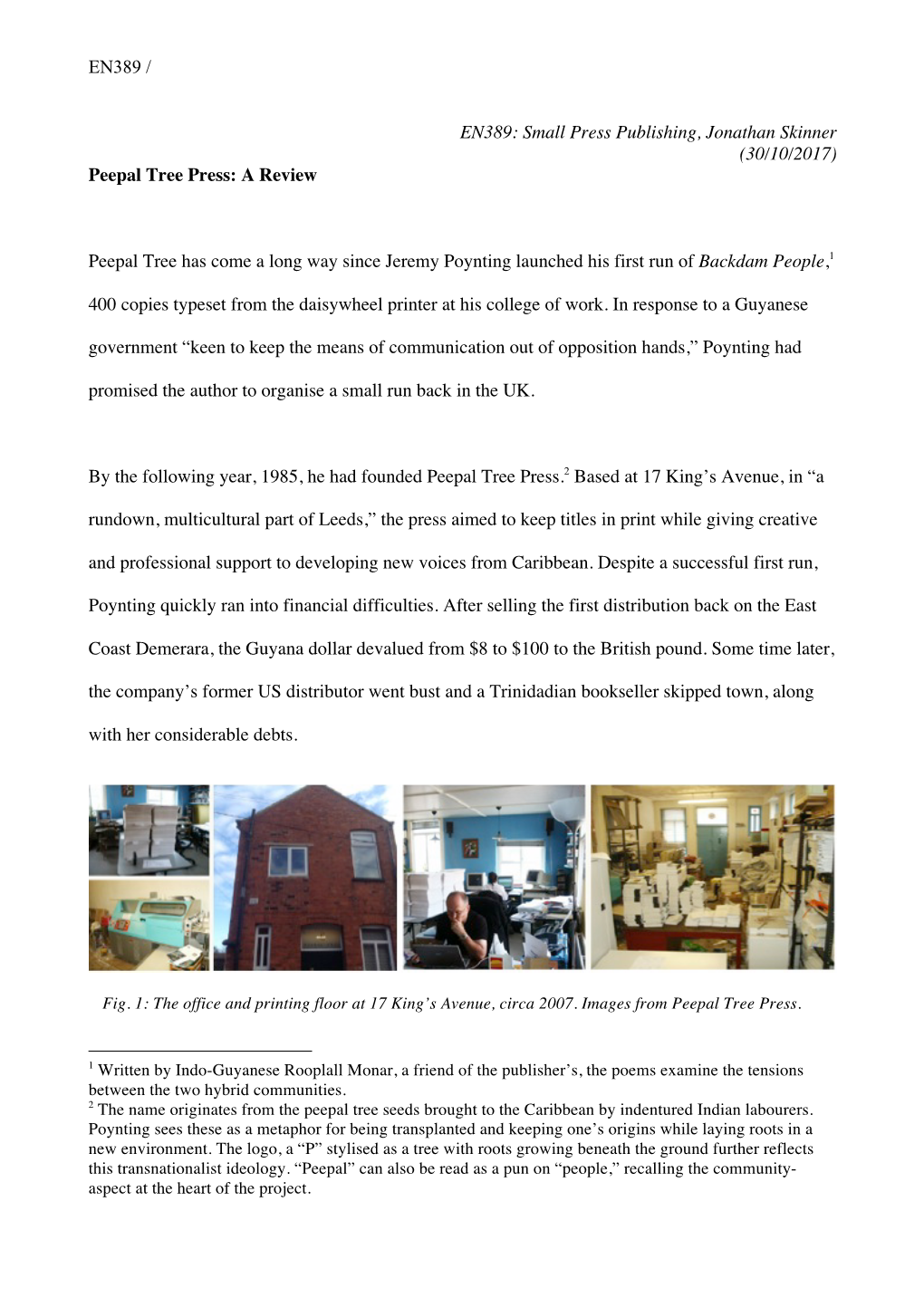

Small Press Publishing, Jonathan Skinner (30/10/2017) Peepal Tree Press: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Document

Below is a list of further reading about Windrush. In this list, you will find an eclectic mix of novels, poetry, plays and non-fiction publications, compiled with the help of Peepal Tree Press, who publish Caribbean and Black British fiction, poetry, literary criticism, memoirs and historical studies. NOVELS, POETRY & PLAYS SMALL ISLAND, ANDREA LEVY (HACHETTE UK) A delicately wrought and profoundly moving novel about empire, prejudice, war and love, Small Island was the unique winner of both the Orange Prize for Fiction and the Whitbread book of the Year, in addition to the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize and the Orange Prize ‘Best of the Best’. Andrea Levy was born in England to Jamaican parents who came to Britain in 1948. After attending writing workshops when she was in her mid-thirties, Levy began to write the novels that she, as a young woman, had always wanted to read – entertaining novels that reflect the experiences of black Britons, which look at Britain and its changing population and at the intimacies that bind British history with that of the Caribbean. IN PRAISE OF LOVE AND CHILDREN, BERYL GILROY (PEEPAL TREE PRESS) After false starts in teaching and social work, Melda Hayley finds her mission in fostering the damaged children of the first generation of black settlers in a deeply racist Britain. Born in what was then British Guiana, Beryl Gilroy moved to the UK in the1950s. She was the author of six novels, two autobiographical books, and she was a pioneering teacher and psychotherapist, becoming London’s first black headteacher. She is considered “one of Britain’s most significant post-war Caribbean migrants”. -

Bookshelf 2017

New West Indian Guide 92 (2018) 80–107 nwig brill.com/nwig Bookshelf 2017 Richard Price and Sally Price Anse Chaudière, 97217 Anses d’Arlet, Martinique [email protected] Once again, in order to provide a window on the current state of Caribbean book publishing for nwig readers and contributors (as well as the authors of books reviewed in the journal), we offer a brief analysis, based on seven of the journal’s most recent issues (volume 89–3&4 [2015] through volume 92–3&4 [2018, not yet published]). Note that because we aim at providing full reviews of more than 50 nonfiction books per issue, this rundown does not include many other books that were published during the relevant period. During this three-and-a-half-year run of issues, we published (or will pub- lish) full reviews of 373 books from 97 publishers. Thirteen publishers pro- vided nine or more titles, accounting for 52 percent of the total, with Palgrave Macmillan contributing the most (27 titles). The others were University Press of Florida (24), University of North Carolina Press (24), University of the West Indies Press (21), Duke University Press (17), University of Virginia Press (15), Routledge (12), Oxford University Press (11), Liverpool University Press (10), Lexington Books (10), Ian Randle (9), University of Mississippi Press (9), and Yale University Press (9). Another 13 publishers contributed 4–8 books each, accounting for 21 percent of books reviewed. The remaining 71 publishers pro- vided 1–3 titles—27 percent of the books reviewed. If we consider the contents of our annual Bookshelf round-up (which, unlike the reviews, includes fiction and poetry), the number of publishers more than doubles (as does the number of books). -

Breaking New Ground: Celebrating

BREAKING NEW GROUND: CELEBRATING BRITISH WRITERS & ILLUSTRATORS OF COLOUR BREAKING NEW GROUND: Work for New Generations BookTrust Contents Represents: 12 reaching more readers by BookTrust Foreword by My time with 5 Speaking Volumes children’s Winter Horses by 14 literature by 9 Uday Thapa Magar Errol Lloyd Our Children Are 6 Reading by Pop Up Projects Reflecting Grandma’s Hair by Realities by Ken Wilson-Max 17 10 the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education Feel Free by Irfan Master 18 Authors and Illustrators by Tiles by Shirin Adl 25 62 Location An Excerpt from John Boyega’s 20 Paper Cup by Full List of Authors Further Reading Catherine Johnson and Illustrators 26 63 and Resources Weird Poster by Author and Our Partners Emily Hughes Illustrator 23 28 Biographies 65 Speaking Volumes ‘To the woman crying Jon Daniel: Afro 66 24 uncontrollably in Supa Hero the next stall’ by 61 Amina Jama 4 CELEBRATING BRITISH WRITERS & ILLUSTRATORS OF COLOUR BREAKING NEW GROUND clear in their article in this publication, we’re in uncertain times, with increasing intolerance and Foreword xenophobia here and around the world reversing previous steps made towards racial equality and social justice. What to do in such times? The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education and BookTrust, who have also contributed to this brochure, point to new generations as the way forward. Research by both organisations shows that literature for young people is even less peaking Volumes is run on passion contribution to the fight for racial equality in the representative of Britain’s multicultural society and a total commitment to reading as arts and, we hoped, beyond. -

P E E P a L T R E E P R E

P E E P A L T R E E P R E S S 2017 Welcome to our 2017 catalogue! Peepal Tree brings you the very best of international writing from the Caribbean, its diasporas and the UK. Founded in 1985, Peepal Tree has published over 370 books and has grown to become the world’s leading publisher of Caribbean and Black British Writing. Our goal is to publish books that make a difference, and though we always want to achieve the best possible sales, we’re most concerned with whether a book will still be alive and have value in the future. Visit us at www.peepaltreepress.com to discover more. Peepal Tree Press 17 Kings Avenue, Leeds LS6 1QS, United Kingdom +44 (0)1 1 3 2451703 contact @ peepaltreepress.com www.peepaltreepress.com Trade Distribution – see back cover Madwoman SHARA MCCALLUM “These wonderful poems open a world of sensation and memory. But it is a world revealed by language, never just controlled. The voice that guides the action here is openhearted and openminded—a lyric presence that never deserts the subject or the reader. Syntax, craft and cadence add to the gathering music from poem to poem with—to use a beautiful phrase from the book, ‘each note tethering sound to meaning.’” —Eavan Boland Sometimes haunting and elusive, but ultimately transformative, the poems in Shara McCallum’s latest collection Madwoman chart and intertwine three stages of a woman’s life from childhood to adulthood to motherhood. Rich with the 9781845233396 / 80 pages / £8.99 POETRY complexities that join these states of being, the poems wrestle with the idea of JANUARY 2017 being girl, woman and mother all at once. -

Including 2016 Titles Visit Us at To

Welcome to our Spring/Summer 2017 catalogue! Including 2016 titles Peepal Tree brings you the very best of international writing from the Caribbean, its diasporas and the UK. Founded in 1985, Peepal Tree has published over 350 books and has grown to become the world’s leading publisher of Caribbean and Black British Writing. Our goal is to publish books that make a difference, and though we always want to achieve the best possible sales, we’re most concerned with whether a book will still be alive and have value in the future. Visit us at www.peepaltreepress.com to discover more. Peepal Tree Press 17 Kings Avenue, Leeds LS6 1QS, United Kingdom +44 (0)1 1 3 2451703 info @ peepaltreepress.com www.peepaltreepress.com 1 Madwoman SHARA MCCALLUM “These wonderful poems open a world of sensation and memory. But it is a world revealed by language, never just controlled. The voice that guides the action here is openhearted and openminded—a lyric presence that never deserts the subject or the reader. Syntax, craft and cadence add to the gathering music from poem to poem with—to use a beautiful phrase from the book, ‘each note tethering sound to meaning.’” —Eavan Boland Sometimes haunting and elusive, but ultimately transformative, the poems in Shara McCallum’s latest collection Madwoman chart and intertwine three stages of a woman’s life from childhood to adulthood to motherhood. Rich with the 9781845233396 / 72 pages / £8.99 POETRY complexities that join these states of being, the poems wrestle with the idea of Print / 23 JAN 2017 being girl, woman and mother all at once. -

Black British Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by York St John University Institutional Repository 12 SARAH LAWSON WELSH Black British Poetry ‘Mekin Histri’: Black British Poetry from the Windrush to the Twenty-First Century The arrival in 1948 of the SS Windrush, a ship carrying more than 280 Jamaicans to Britain marks a foundational, if also a fetishized 1 place in any understanding of post-1945 Black British poetry. Whilst Windrush was not strictly the ‘beginning’ of black migration to Britain, the 1948 British Nationality Act did enable New Commonwealth and Pakistani citizens to enter and settle in Britain with greater freedom than ever before, and Windrush has become a convenient label for this fi rst post-1945 generation of black migrant writers in Britain. This generation’s ‘arrival’, the accelerat- ing endgame of empire, the rise of anti-colonial independence movements and the cultural activity and confi dence which accompanied them, created the conditions for an extraordinary period of literary creativity in Britain, as black and Asian writers came to England to work, to study and to be published. Mainstream presses showed unprecedented interest in publishing Black migrant writers and the beginnings of organized association between writers from different territories in Britain can be also traced to this time. An early forum was the BBC radio programme, Caribbean Voices , conceived by Una Marson in 1943 and subsequently edited by Henry Swanzy (and later V. S. Naipaul) between 1946 and 1958. Caribbean Voices broadcast weekly, live from London to the Caribbean and enabled regular cultural exchanges between Britain and the Caribbean, as well as forging a sense of common black literary endeavour in Britain. -

Free Verse Report

Publishing opportunities for Black and Asian poets www.freeverse.org.uk Editor: Danuta Kean ([email protected]) Project Management: Nick Murza and Emma Hewett (Spread the Word) Quantitative Research and Data Analysis: Melanie Larsen, Nick Murza Contributors: Katy Massey, Valerie Mason-John, Daljit Nagra, Alison Solomon, Kadija George Sesay Poetry Editors: Bernardine Evaristo, Moniza Alvi Special thanks to: Ruth Borthwick, Bernardine Evaristo, Kate Griffin, Moniza Alvi, and Jane Stubbs and all at Spread the Word Advisory panel: Moniza Alvi, Gina Antchandie, Jenny Attala, Ruth Borthwick, Bernardine Evaristo, Kate Griffin, Lucy Hutton, Ann Kellaway, Nick McDowell, Jules Mann, Jane Stubbs, Emma Turnbull Design: Lambeth Communications and Consultation Print: Fox Print Produced by: Spread the Word 77 Lambeth Walk, London SE11 6DX Tel: 020 7735 3111 www.spreadtheword.org.uk www.freeverse.org.uk Research and Report commissioned by Arts Council England, Scottish Arts Council, and Arts Council of Wales www.artscouncil.org.uk www.scottisharts.org.uk www.artswales.org.uk 2 FREE VERSE INTRODUCTION The start of something... Poetry lays claim to be the John Siddique and Moniza Alvi, to marginalised, but were victims of an voice of a nation’s soul. Imtiaz Dharker to Daljit Nagra. insidious institutional racism. CONTENTS To achieve that status, it This is a far cry from the 1980s, when In Full Colour was not about merely 4 The results: the results poetry publishers were making great reporting the situation. It was about must reflect the multitude of the first ever survey of communities that make strides towards cultural diversity with promoting change, and since its such names as John Agard, Benjamin publication book publishers have into opportunities for up that nation. -

P E E P a L T R E E P R E

P E E P A L T R E E P R E S S 2018 About Peepal Tree Press Peepal Tree Press is the world’s largest publisher of Caribbean and Black British fiction, poetry, literary criticism, memoirs and historical studies. Jeremy Poynting, recently awarded the Bocas Henry Swanzy Award for Distinguished Service to Caribbean Letters, is the founder and managing editor. Our team includes Hannah Bannister as operations manager, Kwame Dawes and Jacob Ross as, respectively, associate poetry and fiction editors, Kadija George and Dorothea Smartt as co-directors of the Inscribe programme, Adam Lowe as marketing and social media associate and Paulette Morris despatching orders and looking after our stock. Recent prize successes include the 2018 Casa de la Américas Literary Award for Anthony Kellman’s Tracing Ja Ja; the 2017 Clarissa Luard Award for innovation in publishing; and the 2017 Jhalak Prize for best book by a UK writer of colour, awarded to Jacob Ross for his literary crime novel The Bone Readers. Peepal Tree is a wholly independent company, founded in 1985, and now publishing around 20 books a year. We have published over 370 titles, and are committed to keeping most of them in print. The list features new writers and established voices. In 2009 we launched the Caribbean Modern Classics Series, which restores to print essential books from the past with new introductions. We are grateful for financial support from Arts Council England as a National Portfolio Organisation since 2011; we were a regularly funded organisation from 2006. Arts Council funding allows us to sustain Inscribe, a writer development project that supports writers of African & Asian descent in England.