Written Evidence Submitted by BT Group (COR0171)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BT and Openreach Go Their Separate Ways

BT And Openreach Go Their Separate Ways BT And Openreach Go Their Separate Ways 1 / 2 Nov 29, 2016 — It is one of the most dragged-out divorces in corporate history but it seems that BT and Openreach will definitely go their separate ways. Jul 5, 2016 — We assumed that Three and O2 would keep competing as separate entities ... There is always a competitive tension for mobile network operators (MNOs) in ... We looked at a number of ways in which BT could have tried to harm EE's ... I do not intend to go into great detail on the substance of the case (the .... Another way, although I doubt it will work for liability reasons, would be to contact Facebook ... Is there any way of establishing contact directly with Openreach? ... Get help for all your BT products and services you use at home and on the go.. [12] Since 2005, BT have been accused of abusing their control of Openreach, ... It now required a licence in the same way as any other telecommunications operator. ... The next major development for British Telecommunications, and a move ... BT stated that PlusNet will continue to operate separately out of its Sheffield .... May 21, 2021 — Another way, although I doubt it will work for liability reasons, would be to ... I can't find any other way to contact Openreach on their website. ... Get help for all your BT products and services you use at home and on the go. After this encounter, Bo and Lauren go their separate ways. ... What settings should I use for a fibre router that's connected to a BT Openreach modem? Persons ... -

Annex to the BT Response to Ofcom's Consultation on Promoting Competition and Investment in Fibre Networks – Wholesale Fixed

Annex to the BT response to Ofcom’s consultation on promoting competition and investment in fibre networks – Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review 2021-26 29 May 2020 Non - confidential version Branding: only keep logos if the response is on behalf of more than one brand, i.e. BT/Openreach joint response or BT/EE/Plusnet joint response. Comments should be addressed to: Remove the other brands, or if it is purely a BT BT Group Regulatory Affairs, response remove all 4. BT Centre, London, EC1A 7AJ [email protected] BT RESPONSE TO OFCOM’S CONSULTATION ON COMPETITION AND INVESTMENT IN FIBRE NETWORKS 2 Contents CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................................. 2 A1. COMPASS LEXECON: REVIEW OF OFCOM'S APPROACH TO ASSESSING ULTRAFAST MARKET POWER 3 A2. ALTNET ULTRAFAST DEPLOYMENTS AND INVESTMENT FUNDING ...................................................... 4 A3. EXAMPLES OF INCREASING PRICE PRESSURE IN BUSINESS TENDERING MARKETS .............................. 6 A4. MARKET ANALYSIS AND REMEDIES RELATED TO PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE ................................... 7 Our assessment of Ofcom’s market analysis ............................................................................................ 8 Our assessment of Ofcom’s remedies .................................................................................................... 12 A5. RISKS BORNE BY INVESTORS IN BT’S FIBRE INVESTMENT ................................................................ -

Transformation Solutions, Unlocking Value for Clients

CEO Study Telecom Implementations Chris Pearson Global Business Consulting Industry Leader 21.11.2008 1 IBM Telecom Industry Agenda . CEO Study – Enterprise of the Future . IBM’s view of the Telecom market . IP Economy . The Change agenda . World is becoming Smarter 2 Storm Warning | ZA Lozinski | Clouds v0.0 - September 2008 | IBM Confidential © 2008 IBM Corporation We spoke toIBM 1,130 Telecom CEOs Industry and conducted in-depth analyses to identify the characteristics of the Enterprise of the Future How are organizations addressing . New and changing customers – changes at the end of the value chain . Global integration – changes within the value chain . Business model innovation – their response to these changes Scope and Approach: 1,130 CEOs and Public Sector Leaders . One-hour interviews using a structured questionnaire . 78% Private and 22% Public Sector . Representative sample across 32 industries . 33% Asia, 36% EMEA, 31% Americas . 80% Established and 20% Emerging Economies Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative . Respondents’ current behavior, investment patterns and future intent . Choices made by financial outperformers . Multivariate analysis to identify clusters of responses . Selective case studies of companies that excel in specific areas 3 Storm Warning | ZA Lozinski | Clouds v0.0 - September 2008 | IBM Confidential © 2008 IBM Corporation IBM Telecom Industry The Enterprise of the Future is . 1 2 3 4 5 Hungry Innovative Globally Disruptive Genuine, for beyond integrated by not just change customer nature generous imagination 4 Storm Warning | ZA Lozinski | Clouds v0.0 - September 2008 | IBM Confidential © 2008 IBM Corporation Telecom CEOsIBM Telecom anticipate Industry more change ahead; are adjusting business models; investing in innovation and new capabilities Telecom CEOs : Hungry . -

Order of the President (Amendment And

IN THE COMPETITION Case No.: 1278/5/7/17 APPEAL TRIBUNAL B E T W E E N: (1) BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS PLC (2) EE LIMITED (3) PLUSNET PLC (4) DABS.COM LIMITED Claimants -v- (1) MASTERCARD INCORPORATED (2) MASTERCARD INTERNATIONAL INCORPORATED (3) MASTERCARD EUROPE SA Defendants _____________________________________________________________________ ORDER _____________________________________________________________________ HAVING REGARD TO the Tribunal’s Reasoned Order of 28 September 2017 AND UPON reading the Claimants’ application made on 18 October 2017 (the “Application”) under rules 31(2) and 32(1)(b) of the Competition Appeal Tribunal Rules 2015 (the “Tribunal Rules”) for permission: (i) to amend the Claim Form and Particulars of Claim; and (ii) to serve the claim outside the jurisdiction on the First and Second Defendants IT IS ORDERED THAT: 1. The Claimants be permitted to amend the Claim Form and Particulars of Claim in the form of the draft attached to the Application. 2. The Claimants be permitted to serve the Amended Claim Form and Particulars of Claim on First and Second Defendants outside the jurisdiction. 3. This order is without prejudice to the rights of the First and Second Defendants to apply pursuant to rule 34 of the Tribunal Rules to dispute the jurisdiction. REASONS 1. The claim and an application for service out of jurisdiction on the First and Second Defendants were filed at the Tribunal on 12 September 2017. Pursuant to that Application, I granted permission for service out for the reasons set out in my Order of 28 September 2017. After Directions for Service were sent to the Claimants, the Claimants’ solicitors became aware that on 15 September 2017 the Fourth Claimant, which at the time the claim was filed was a public company, had re-registered as a private limited company. -

Annual Report & Accounts 1998

Annual report and accounts 1998 Chairman’s statement The 1998 financial year proved to be a very Turnover has grown by 4.7 per cent and we important chapter in the BT story, even if not have seen strong growth in demand. Customers quite in the way we anticipated 12 months ago. have benefited from sound quality of service, price cuts worth over £750 million in the year, This time last year, we expected that there was a and a range of new and exciting services. Our good chance that our prospective merger with MCI Internet-related business is growing fast and we Communications Corporation would be completed are seeing considerable demand for second lines by the end of the calendar year. In the event, of and ISDN connections. We have also announced course, this did not happen. WorldCom tabled a a major upgrade to our broadband network to considerably higher bid for MCI and we did not match the ever-increasing volumes of data we feel that it would be in shareholders’ best interests are required to carry. to match it. Earnings per share were 26.7 pence and I am In our view, the preferable course was to pleased to report a final dividend for the year of accept the offer WorldCom made for our 20 per 11.45 pence per share, which brings the total cent holding in MCI. On completion of the dividend for the year to 19 pence per share, MCI/WorldCom merger, BT will receive around which is as forecast. This represents an increase US$7 billion (more than £4 billion). -

BT Group Regulatory Affairs, Response Remove All 4

Annex to the BT response to Ofcom’s consultation on promoting competition and investment in fibre networks – Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review 2021-26 29 May 2020 Non - confidential version Branding: only keep logos if the response is on behalf of more than one brand, i.e. BT/Openreach joint response or BT/EE/Plusnet joint response. Comments should be addressed to: Remove the other brands, or if it is purely a BT BT Group Regulatory Affairs, response remove all 4. BT Centre, London, EC1A 7AJ [email protected] BT RESPONSE TO OFCOM’S CONSULTATION ON COMPETITION AND INVESTMENT IN FIBRE NETWORKS 2 Contents CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................................. 2 A1. COMPASS LEXECON: REVIEW OF OFCOM'S APPROACH TO ASSESSING ULTRAFAST MARKET POWER 3 A2. ALTNET ULTRAFAST DEPLOYMENTS AND INVESTMENT FUNDING ...................................................... 4 A3. EXAMPLES OF INCREASING PRICE PRESSURE IN BUSINESS TENDERING MARKETS .............................. 6 A4. MARKET ANALYSIS AND REMEDIES RELATED TO PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE ................................... 7 Our assessment of Ofcom’s market analysis ............................................................................................ 8 Our assessment of Ofcom’s remedies .................................................................................................... 12 A5. RISKS BORNE BY INVESTORS IN BT’S FIBRE INVESTMENT ................................................................ -

Anticipated Acquisition by BT Group Plc of EE Limited

Anticipated acquisition by BT Group plc of EE Limited Appendices and glossary Appendix A: Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Appendix B: Industry background Appendix C: Financial performance of companies Appendix D: Regulation Appendix E: Transaction and merger rationale Appendix F: Retail mobile Appendix G: Spectrum, capacity, and speed Appendix H: Fixed-mobile bundles Appendix I: Wholesale mobile: total foreclosure analysis Appendix J: Wholesale mobile: partial foreclosure analysis Appendix K: Mobile backhaul: input foreclosure Appendix L: Retail fixed broadband: Market A Appendix M: Retail broadband: superfast broadband Glossary APPENDIX A Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Terms of reference 1. In exercise of its duty under section 33(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (the Act) the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) believes that it is or may be the case that: (a) arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation in that: (i) enterprises carried on by, or under the control of, BT Group plc will cease to be distinct from enterprises currently carried on by, or under the control of, EE Limited; and (ii) section 23(1)(b) of the Act is satisfied; and (b) the creation of that situation may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition within a market or markets in the United Kingdom (the UK) for goods or services, including the supply of: (i) wholesale access and call origination services to mobile virtual network operators; and (ii) fibre mobile backhaul services to mobile network operators. -

BT Group Plc Annual Report 2020 BT Group Plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic Report 1

BT Group plc Group BT Annual Report 2020 Beyond Limits BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic report 1 New BT Halo. ... of new products and services Contents Combining the We launched BT Halo, We’re best of 4G, 5G our best ever converged Strategic report connectivity package. and fibre. ... of flexible TV A message from our Chairman 2 A message from our Chief Executive 4 packages About BT 6 investing Our range of new flexible TV Executive Committee 8 packages aims to disrupt the Customers and markets 10 UK’s pay TV market and keep Regulatory update 12 pace with the rising tide of in the streamers. Our business model 14 Our strategy 16 Strategic progress 18 ... of next generation Our stakeholders 24 future... fibre broadband Culture and colleagues 30 We expect to invest around Introducing the Colleague Board 32 £12bn to connect 20m Section 172 statement 34 premises by mid-to-late-20s Non-financial information statement 35 if the conditions are right. Digital impact and sustainability 36 Our key performance indicators 40 Our performance as a sustainable and responsible business 42 ... of our Group performance 43 A letter from the Chair of Openreach 51 best-in-class How we manage risk 52 network ... to keep us all Our principal risks and uncertainties 53 5G makes a measurable connected Viability statement 64 difference to everyday During the pandemic, experiences and opens we’re helping those who up even more exciting need us the most. Corporate governance report 65 new experiences. Financial statements 117 .. -

BT Strategic Report

BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic report 1 New BT Halo. ... of new products and services Contents Combining the We launched BT Halo, We’re best of 4G, 5G our best ever converged Strategic report connectivity package. and fibre. ... of flexible TV A message from our Chairman 2 A message from our Chief Executive 4 packages About BT 6 investing Our range of new flexible TV Executive Committee 8 packages aims to disrupt the Customers and markets 10 UK’s pay TV market and keep Regulatory update 12 pace with the rising tide of in the streamers. Our business model 14 Our strategy 16 Strategic progress 18 ... of next generation Our stakeholders 24 future... fibre broadband Culture and colleagues 30 We expect to invest around Introducing the Colleague Board 32 £12bn to connect 20m Section 172 statement 34 premises by mid-to-late-20s Non-financial information statement 35 if the conditions are right. Digital impact and sustainability 36 Our key performance indicators 40 Our performance as a sustainable and responsible business 42 ... of our Group performance 43 A letter from the Chair of Openreach 51 best-in-class How we manage risk 52 network ... to keep us all Our principal risks and uncertainties 53 5G makes a measurable connected Viability statement 64 difference to everyday During the pandemic, experiences and opens we’re helping those who up even more exciting need us the most. Corporate governance report 65 new experiences. Financial statements 117 ... to enable Additional information 204 a safer world This year, we used artificial intelligence (AI) Look out for these throughout the report: to anticipate emerging threats and help protect the nation from up to 4,000 cyberattacks a day. -

Openreach Progress with Implementation of the New Arrangements Between Openreach and BT

Openreach progress with Implementation of the new arrangements between Openreach and BT Report to Ofcom’s Openreach Monitoring Unit June 2019 Foreword Openreach is a wholesale network provider. We support more than 600 Communications Providers (CPs) to connect the 30 million UK homes and business to their networks. We sell our products and services to CPs so they can add their own products and provide their customers with bundled landline, mobile, broadband, TV and data services. Our services are available to everybody and our products have the same prices, terms and conditions, no matter who buys them. This report is provided by Openreach Limited1 to Ofcom’s Openreach Monitoring Unit as input to its forthcoming Commitments Implementation Report. 1 Openreach Limited is a wholly-owned subsidiary of BT Group Plc. Non-Confidential Version Page 2 of 52 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................ 2 I. Executive Summary ................................................................................. 5 II. Introduction ............................................................................................. 9 III. Implementation: Setting up Openreach Limited .................................... 10 IV. Openreach Rebranding .......................................................................... 12 ‘Scrub and Buff’ ........................................................................................................ 12 New van livery ........................................................................................................ -

The Economics of Next Generation Access - Final Report

WIK-Consult • Report Study for the European Competitive Telecommunication Association (ECTA) The Economics of Next Generation Access - Final Report Authors: Dieter Elixmann Dragan Ilic Dr. Karl-Heinz Neumann Dr. Thomas Plückebaum WIK-Consult GmbH Rhöndorfer Str. 68 53604 Bad Honnef Germany Bad Honnef, September 10, 2008 The Economics of Next Generation Access I Contents Tables IV Figures VII Abbreviations X Preface XIII Executive Summary XV 1 Introduction 1 2 Literature review 3 2.1 OPTA: Business cases for broadband access 3 2.1.1 OPTA: Business case for sub-loop unbundling in the Netherlands 3 2.1.2 OPTA: Business case for fibre-based access in the Netherlands 5 2.2 Comreg: Business case for sub-loop unbundling in Dublin 8 2.3 BIPT: The business case for sub-loop unbundling in Belgium 10 2.4 Analysys: Fibre in the Last Mile 12 2.5 Avisem studies for ARCEP 15 2.5.1 Sharing of the terminal part of FTTH 16 2.5.2 Intervention of local authorities as facilitators 18 2.6 AT Kearney: FTTH for Greece 19 2.7 ERG opinion on regulatory principles of NGA 23 2.8 JP Morgan: The fibre battle 26 2.9 OECD 28 2.9.1 Public rights of way for fibre deployment to the home 29 2.9.2 Developments in fibre technologies and investment 32 3 Experiences in non-European countries 44 3.1 Australia 44 3.1.1 Overall broadband market penetration 44 3.1.2 Current broadband market structure 45 3.1.3 Envisaged nationwide “Fibre to the Node” network 47 3.1.4 Regulation, wholesale services 50 3.2 Japan 51 3.2.1 Overall broadband market penetration 51 II The Economics of -

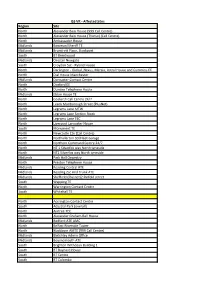

LTB 342.2019 Attachment 1

ISS VR - Affected Sites Region Site North Alexander Bain House (999 Call Centre) North Alexander Bain House (Thurso) (Call Centre) North Ambassador House Midlands Bowman/Sheriff TE Midlands Brundrett Place, Stockport South BT Brentwood Midlands Chester Newgate South Croydon Ssc - Ryland House North Darlington - Global ,Nexus, Mercia, Astral House and Cummins EE North Dial House Manchester Midlands Doncaster Contact Centre North Doxford EE North Dundee Telephone House Midlands Eldon House TE North Gosforth Call Centre 24/7 North Leeds Marlborough Street (PlusNet) North Legrams Lane MTW North Legrams Lane Section Stock North Legrams Lane TEC North Liverpool Lancaster House South Monument TE North Newcastle Cte (Call Centre) North Northallerton SD/Fleet Garage North Northern Command Centre 24/7 North NT 1 Silverfox way North tyneside North NT2 Silverfox way North tyneside Midlands Park Hall Oswestry North Preston Telephone House Midlands Reading Central ATE Midlands Reading Zsc And Trunk ATE Midlands Sheffield (Plusnet)2 Pinfold street South Wapping TE North Warrington Contact Centre South Whitehall TE North Accrington Contact Centre South Adastral Park (overall) North Aintree TEC North Alexander Graham Bell House Midlands Bedford ATE AMC North Belfast Riverside Tower North Blackburn AMTE (999 Call Centre) Midlands Bletchley Admin Office Midlands Bournemouth ATE South Brighton Withdean Building 1 South BT Baynard House South BT Centre South BT Colombo South BT Mill House South BT Tower South Canterbury Becket House South Crawley New TEC