Nber Working Paper Series Footloose and Pollution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gareth Owen Theatrical Sound Designer

Gareth Owen Theatrical Sound Designer Musical Theatre Sound Design Awards highlights include : Outer Critics Circle Award COME FROM AWAY Schoenfeld, New York Olivier Award MEMPHIS Shaftesbury Theatre, London Craig Noel Award COME FROM AWAY La Jolla Playhouse, San Diego Pro Sound Award MEMPHIS Shaftesbury Theatre, London Olivier Award MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG Comedy Theatre, London Olivier Nomination TOP HAT Aldwych Theatre, London Tony Nomination END OF THE RAINBOW Belasco Theatre, New York Olivier Nomination END OF THE RAINBOW Trafalgar Studios, London Tony Nomination A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC Walter Kerr, New York Upcoming Sound Design highlights include : Susan Stroman’s YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN on London’s West End; Stephen Schwartz’s PRINCE OF EGYPT (World Premiere), and Des McAnuff’s DONNA SUMMER PROJECT both on Broadway; COME FROM AWAY in Toronto and on tour in the USA; Don Black’s THE THIRD MAN (World Premiere) in Vienna; BODYGUARD in Madrid; and the JERSEY BOYS International Tour. International Musical Sound Design highlights include : Lead Producer Director A BRONX TALE (World Première) Long Acre, Broadway Dodgers Theatrical Robert DeNiro COME FROM AWAY (World Première) Schoenfeld, Broadway Junkyard Dog Chris Ashley STRICTLY BALLROOM (European Première) Worldwide (2 versions) Global Creatures Drew McConie DISNEY’S HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME Worldwide (5 versions) Disney Scott Schwartz SCHIKANEDER (World Premiere) Raimund, Vienna Stephen Schwartz & VBM Trevor Nunn CINDERELLA Rossia, Moscow Stage Entertainment Lindsay Posner SECRET GARDEN Lincoln -

Julianne Hough

| COVER STORY | THE WELL LET’S HEAR IT FOR THE GIRL Loose-limbed celebrity dancer-cum singer JULIANNE HOUGH talks to JOE YOGERST about her love of dance, her artistic aspirations, her English accent – and the uncanny omnipresence of the musical Footloose in her life PHOTOGRAPHY / MARK LIDDELL STYLING / LISA MICHELLE BOYD, OPUS BEAUTY HAIR / CAMPBELL F MCAULEY, SOLO ARTISTS, USING SYDNEY HAIR CARE MAKE-UP / SPENCER BARNES, SOLO ARTISTS, USING ARMANI COSMETICS DRESS: PRADA DECEMBER 2011 – PRESTIGE – 239 THE WELL | COVER STORY | ulianne hough is back home in Los the film version of the hit Broadway musical Angeles, taking a well-deserved break from Rock of Ages, due for release in June 2012. the worldwide publicity blitz that precedes Twenty or 30 years from now, some young the remake of Footloose, a movie about young ingénue is going to star as Julianne Hough people who would do just about anything in a biopic about the dancer’s younger days, to dance. That’s pretty much been the story because her lead-up to fame and fortune of Hough’s life, too, a relentless and often reads like a real-life version of Flashdance, or exhausting endeavour to become one of the one of those other small-town-girl-makes- globe’s leading dancers. good movies. Once upon a time, it was ballet that She was born and raised into a large (five launched dancers (such as Rudolf Nureyev kids) Mormon family on the edge of Salt Lake and Mikhail Baryshnikov) into stardom City. But unlike the movie story, these were beyond their immediate circle and to parallel small-town folks who loved to dance. -

REV-Digital-Playbill-Footloose.Pdf

1 Finding inspiration is important. At M&T Bank, we understand how important the arts are to a vibrant community. That’s why we offer our time, energy and resources to support artists of all kinds, and encourage others to do the same. Learn more at mtb.com. Equal Housing Lender. ©2018 M&T Bank. Member FDIC. 2 Serving Hometowns Since 1870 mygenbank.com | 315.568.5855 3 The rev Administrative staff Jessica Alexander Ed Bauso Lauren Bice Director of Audience Marketing Administrative Services/Grant Manager Assistant Assistant Melissa Carbonaro Lisa Chase Billy Goheen Business Director of Company Mgmt. Manager Education Apprentice Geoffrey Howard Tiffany Howard Nancy Hunt Technical Director, Costume Shop Audience Services Education Manager/Designer Associate Michael Iannelli Erin Katzker Josh Katzker Director of Production Educational Artistic Associate/ & Operations Theatre Manager PiTCH Coordinator Lynnette Lee Rocky Love Christopher Lynch Managing Technical Company Director Director Manager Dylan Parmenter Marshall Pope Lisa Robillard Facilities & Vehicles Props Master Audience Services Manager Manager Olivia Semsel Brett Smock Ashley Wilson Marketing Producing Wardrobe/Rentals Manager Artistic Director Supervisor The rev board of directors Kelly Wejko Roberta Williams Connie Bouck Susie Gaynes Secretary nd President 1st Vice President 2 Vice President Cayuga County WHMB P.C. Supreme & County Court Cathy Benson Joe Bartolotta Patrick Carbonaro Treasurer Bill Abdallah JBJ Real Property Carbanaro Law CFCU Community Offices, P.C. Credit Union Matt Chalanick Denise Driscoll Menzo Case Peggy Dickman Charles T. Driscoll Generations Bank The Real Estate Dickman Farms Agency Masonry Restoration Co., Inc. Diana Gagliostro David Tehan Angela Winfield Judy Foresman Muldoon Dry Cleaners, Inc. -

The Big One-Oh! a Letter from Charley (Actor Aaron Banes)

C TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I | THE PLAY Synopsis Setting Themes Characters SECTION II | THE CAST & CREATIVE TEAM Creative Biographies Cast List Behind the Scenes Look SECTION III | YOUR STUDENTS AS AUDIENCE Theater Vocabulary Vocabulary from The Big One-Oh! A Letter from Charley (Actor Aaron Banes) SECTION IV | YOUR STUDENTS AS ACTORS Reading a Scene for Understanding Scene/Character Analysis SECTION V | YOUR STUDENTS AS ARTISTS Warm-up: “I Am a Tree” Explode the Moment! Drawing to Write Activity Thumbs Up Or Thumbs Down? Common Core & DOE Theater Blueprint SECTION VI | THE ATLANTIC LEGACY 2 SECTION I: THE PLAY Synopsis Setting Themes Characters 3 SYNOPSIS Charley Maplewood has never been one for parties—that would require friends, which he doesn’t have. Well, unless you count his monster friends, but they’re only imaginary. But now that he’s turning ten—the big one-oh—he decides to throw a birthday party for himself, complete with a “House of Horrors” theme. Of course things don’t work out as he plans. Will Charley be able to pull it together before the big one-oh . becomes the big OH-NO!? TIME Present Day SETTING Fresno, California. THEMES • Making new friends • Change and transition • Being yourself • Being the “new kid” at school 4 CHARACTERS Charley: An almost ten-year-old who has just moved to town. Boing-Boing: Charley’s dog, a puppet. Mom: Charley’s mom. Dad: Charley’s dad, lives in Scotland. Lorena: Charley’s sixteen-year-old sister. So Lame #1: Lorena’s back-up singer. So Lame #2: Lorena’s back-up singer. -

FOOTLOOSE; the MUSICAL - by Dean Pitchford and Walter Bobbie

FOOTLOOSE; THE MUSICAL - by Dean Pitchford and Walter Bobbie July 10 - August 2, 2009 Director – Mark Valahovic Musical Director – Tanya K Manwill Choreographer – Edwin Roa Lighting Designer – Larry Hugo Set Designer – Kevin Riddle Costume Designer – Meredith Heiderman Sound Designer – Ben Clore Production Stage Manager – Bob Button Producer – Satch Huizenga Asst Director – Rebecca Willingham Asst Stage Manager – Evan Lang Dance Captain – Katherine Baird Properties – Mandy & Lindsay McDavid Master Painter – Mary Butcher Master Electrician – Scott Keith Light Board Technician – Jill Urquhart Sound Board Technician – Matt Miller Follow Spot Operator – Tiffany Ames Hair & Makeup Designer – Daphne D’earth Latham Costume Assistants – Karie Reed, Jill Urquhart MUSICIAN/MENTORS PIANO – Erica Umback DRUMS/PERCUSSION – April Martin GUITAR/BASS – Jim Polson BASS – Hardy Douglas GUITAR/BASS/WOODWINDS – Mike D’Antoni Woodwinds – Laura DiPuma MUSICIAN/APPRENTICES PIANO – Claire Wiley DRUMS/PERCUSSION – Joey Ballard BASS GUITAR – Will Bollinger TRUMPET – Emily Kuhn SAXOPHONES – Carolyn McKenzie OBOE – Julia Perry CAST REN McCORMACK – Richie MacLeod ETHEL McCORMACK – Courtney Thompson REVEREND SHAW MOORE – Jacob Canon VI MOORE – Gabrielle Laskey ARIEL MOORE – Veronica Lowry LULU WARNICKER – Joy Tanksley WES WARNICKER – Trent Manwill COACH ROGER DUNBAR/A COP – Scott Dunn ELEANOR DUNBAR – Jessica Wilbert RUSTY – Kelsey Fehlner URLEEN – Brittanie Pleasants WENDY JO – Ali Stoner CHUCK CRANSTON – Chris Moneymaker LYLE – Kevin Snyder TRAVIS/COYBOY BOB – Gage Jenkins BETSY BLAST – Jane McDonald WILLARD HEWITT – Jacob Lyon JETER – Ronald Stewart BICKLE – Josh Tucker GARVIN – Corbin Puryear ENSEMBLE/DANCERS – Carly Amburn, Katherine Baird, Ally Boate, Caitlin Hunt, Anna Webster, Brittany Yount . -

FOOTLOOSE CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS from the Author: the Major Characters in Footloose Have One Trait in Common: They Are All Survivors

FOOTLOOSE CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS From the author: The major characters in Footloose have one trait in common: they are all survivors. Their circumstances, no matter how tragic, have not defeated them. As a consequence, the audience finds them likable, sympathetic, and human. This means that each role is unique and presents the actor with specific challenges. Thumbnail sketches of some of these characters are provided below. There will be a lot of support with dancing. The show will be choreographed in a way that stretches students’ dancing abilities without hindering their performances. If you do not consider yourself a dancer, see learning choreography as another step in your education as a theatrical performer. MALE CHARACTERS REN MCCORMACK (Leading role, dancer) A teenage boy from Chicago. Ideally, Ren must sing and dance – and he must also be fairly witty. Ren is a joker who enjoys a good time (which is why his pals are upset to find out he’s leaving Chicago in the opening number). Lately though, his fun-loving attitude has taken on a tone of desperation. He is trying too hard to convince the world, and himself, that his father’s desertion hasn’t wounded him as deeply as it has. Ariel is the first character to get Ren to talk about that sticky subject. Sharing that intimacy early on becomes the basis for Ren’s and Ariel’s relationship. Ren’s emotional journey starts with his being feisty and flippant in Act 1, continues through his thoughtful argument to the Town Council, and ends with this emotional final confrontation with Reverend Moore. -

FIDDLER on the ROOF Is Presented with Special Arrangement with Music Theatre Internatio Bethany Public Schools Administration

FIDDLER ON THE ROOF is presented with special arrangement with Music Theatre Internatio Bethany Public Schools Administration Superintendent Middle School Principal Drew Eichelberger Trey Keoppel Elementary Principal High School Principal Reuben Bellows Mark Melton Director Annie Mann Vocal Director Joanie Gregory-Pullen Technical Director & Choregrapher Steveanne Bielich Pit Orchestra Director Steve Sharp Assistant Vocal Director Christine Wagner Guest Director Tabitha Fine FOOTLOOSE Stage Adaptation by DEAN PITCHFORD and WALTER BOBBIE Based on the original screenplay by Dean Pitchford Music by TOM SNOW Lyrics by DEAN PITCHFORD Additonal music by ERIC CARMEN, SAMMY HAGAR, KENNY LOGGINS and JIM STEINMAN Footloose Cast Ren McCormack..............................................................................................................................Ian Walsh Reverend Shaw Moore................................................................................................................Luke Spear Ariel Moore...................................................................................................................................Nolia Sweatt Vi Moore................................................................................................................................ ......Brooke Sailer Ethel McCormack.......................................................................................................................Bella Warner Williard Hewitt........................................................................................................... -

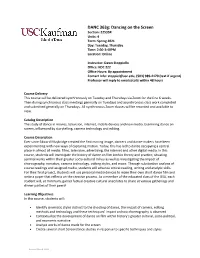

DANC 363G Syllabus S21

DANC 363g: Dancing on the Screen Section: 22535R Units: 4 Term: Spring 2021 Day: Tuesday, Thursday Time: 2:00-3:40PM Location: Online Instructor: Dawn Stoppiello Office: KDC 222 Office Hours: By appointment Contact Info: [email protected], (503) 989-4170 (text if urgent) Professor will reply to emails/calls within 48 hours Course Delivery This course will be delivered synchronously on Tuesday and Thursdays via Zoom for the first 6 weeks. Then during synchronous class meetings generally on Tuesdays and asynchronous class work completed and submitted generally on Thursdays. All synchronous Zoom classes will be recorded and available to view. Catalog Description The study of dance in movies, television, internet, mobile devices and new media. Examining dance on screen, influenced by storytelling, camera technology and editing. Course Description Ever since Edward Muybridge created the first moving image, dancers and dance-makers have been experimenting with new ways of capturing motion. Today, this has led to dance occupying a central place in almost all media: films, television, advertising, the internet and other digital media. In this course, students will investigate the history of dance on film both in theory and practice, situating seminal works within their greater socio-cultural milieu as well as investigating the impact of choreography, narrative, camera technology, editing styles, and music. Through substantive analysis of course readings and assigned media, students will advance critical reading, writing and analytic skills. For their final project, students will use personal media devices to make their own short dance film and write a paper that reflects on the creative process. -

Fear and Dancing” 2 Samuel 6:1-19

1 Rev. Kate S. Forer Presbyterian-New England Congregational Church October 20, 2019 “Fear and Dancing” 2 Samuel 6:1-19 The worst happened. His teenage son died. His teenage son died on his way home from a night of dancing and probably drunken debauchery and here he was the town minister, the Reverend. How was he going to keep it together enough to minister to his own congregation? His wife? His daughter? How was he going to face life without Bobby, his only son, his first born? The Reverend liked things under control. He ran a tight ship at home and at his church and he had told his son time and time again about drinking and driving. He had told him. He had warned him. If he couldn’t protect his own son from meeting such a fate, how was he ever going to protect the rest of the children in this town, whom he loved as well? They can’t keep teenagers from driving – that would never work. They keep trying to stop them from drinking. And so now… they’ll prohibit dancing. No dancing allowed. If the kids can’t go dancing, they won’t congregate and drink so much. No dancing. That’s it. A quiet town. A safe town. A God-fearing town. Until… Ren McCormick arrives. Now, if you’re a child of the 80s like me, you might have begun to recognize the plot to the movie Footloose.1 Footloose, made in 1984, is based on the real town of Elmore City, Oklahoma. -

Footloose :: Rogerebert.Com :: Reviews

movie reviews Reviews Great Movies Answer Man People Commentary Festivals Oscars Glossary One-Minute Reviews Letters Roger Ebert's Journal Scanners Store News Sports Business Entertainment Classifieds Columnists search FOOTLOOSE (PG-13) Ebert: Users: You: Rate this movie right now GO Search powered by YAHOO! register You are not logged in. Log in » Subscribe to weekly newsletter » times & tickets in theaters Fandango Search movie Margin Call showtimes and buy Footloose Mighty Macs tickets. The Mill and the Cross Norman BY ROGER EBERT / October 12, 2011 Paranormal Activity 3 The Skin I Live In about us There's one thing to be said Texas Killing Fields for a remake of a 1984 About the site » movie that uses the cast & credits more current releases » original's screenplay. This one-minute movie reviews Site FAQs » 2011 version is so similar Ren Kenny Wormald — sometimes song for song Ariel Julianne Hough Contact us » and line for line — that I Rev. Moore Dennis Quaid still playing was wickedly tempted to Email the Movie Vi Andie MacDowell Answer Man » reprint my 1984 review, Chuck Patrick John Flueger Dolphin Tale word for word. But That Willard Miles Teller Amigo Would be Wrong. I think I Wes Ray McKinnon Another Earth on sale now could have gotten away Attack the Block with it, though. The movies Bellflower Paramount presents a film directed differ in such tiny details The Big Year by Craig Brewer. Written by Dean (the hero now moves to Blackthorn Tennessee from Pitchford and Brewer, based on Brighton Rock Massachusetts, not Pitchford’s 1984 screenplay. -

Various Footloose (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Footloose (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Stage & Screen Album: Footloose (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Country: India Released: 1984 Style: Soundtrack, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1614 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1505 mb WMA version RAR size: 1334 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 696 Other Formats: AA MP4 MIDI DMF MPC MP2 XM Tracklist Hide Credits Footloose Backing Vocals – Marilyn Dorman, Richey Washington, Steve Wood Bass – Nathan EastDrums – Tris ImbodenGuitar – Buzz Feiten*Keyboards – Neil –Kenny A1 Larsen, Steve Wood Management [Kenny Loggins Management] – Larry 3:48 Loggins LarsonPercussion – Paulinho Da CostaProducer [Additional Production] – Lee DeCarloProducer, Written-By – Kenny LogginsRemix – Humberto GaticaSynthesizer [Bass], Percussion – Michael Boddicker Let's Hear It For The Boy Backing Vocals – George Merrill, Shannon RubicamGuitar – Paul Jackson*Management [Deniece Williams Management] – Alan Mink, –Deniece A2 International Artists Mgmt*, Myrna WilliamsMixed By – Erik Zobler, Tom 4:22 Williams Perry, Tommy VicariPercussion – Paulinho Da CostaProducer – George DukeSynthesizer [Prophet V], Synthesizer [Mini-Moog], Drums [Linn Drums], Synthesizer [Memory Moog] – George DukeWritten-By – Tom Snow Almost Paradise...Love Theme From FOOTLOOSE Bass, Acoustic Guitar – Keith OlsenDrums – Jim KeltnerElectric Guitar – Chas –Mike Reno SandfordKeyboards, Synthesizer – Bill CuomoManagement [Ann Wilson/Heart A3 And Ann Management] – Ken KinnearManagement [Mike Reno/Loverboy -

Footloose! the Musical

………PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE • DATED MATERIAL TO: Arts & Entertainment / Features Departments FROM: Landmark Community Theatre At The THOMASTON OPERA HOUSE 158 Main Street Thomaston, CT 06787 CONTACT: Jeffery Dunn (860) 283-6250 FOOTLOOSE! THE MUSICAL Landmark Community Theatre (LCT) will present FOOTLOOSE! The Musical for eight (8) performances beginning July 14th and running through July 29th, 2012 at the historic Thomaston Opera House. FOOTLOOSE! will mark the second full-length community theatre production on the Thomaston stage after the success of Meredeth Wilson's The Music Man in April 2012. After shutting its door in December of 2010, the Thomaston Opera House was contracted to LCT to manage the Opera House after a long RFP process, followed by negotiations, and finally, overwhelmingly approved by a town vote earlier this year. FOOTLOOSE! is the second of four community theatre productions LCT will produce this year in addition to managing day-to-day operations of the facility. Additional one-night events and rentals by other organizations will also be part of the regular LCT offerings throughout the year. Landmark Community Theatre's production of FOOTLOOSE! features Rob Girardin as Ren McCormack, a city boy who comes to a small town where rock music and dancing have been banned, Nina Paganucci as the Reverend's daughter, Ariel Moore, and Tony Sposato as the Reverend Shaw Moore. Other featured cast members include Jack Saleeby as Willard Hewitt, Reuben Soto as Chuck Cranston, Kristina Johnston as Rusty, Catherine Quirk as Vi Moore, Samantha Putko as Wendy Jo, and Victoria Beaudoin as Urleen. The production is both directed and choreographed by Foster Evan Reese, with musical direction by AJ Bunel.