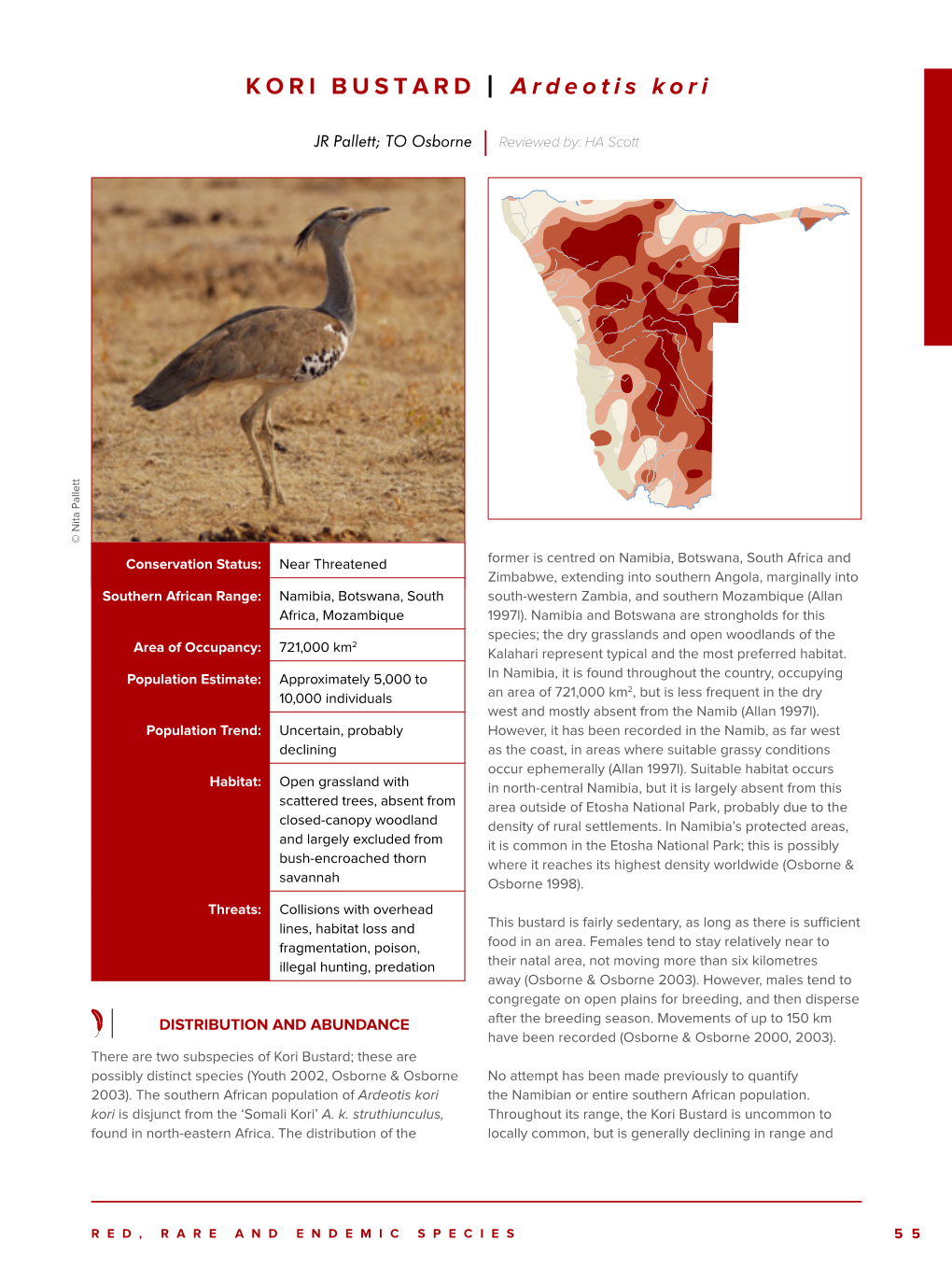

KORI BUSTARD | Ardeotis Kori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sorghum Edited.Cdr

Agricultural Productivity Program for Southern Africa (APPSA) Agricultural Productivity Program for Southern Sorghum Production Guide Africa (APPSA) Agricultural Productivity Program for Southern Africa (APPSA) Agricultural Productivity Program for Southern Africa (APPSA) Table of Contents Foreword ii Acknowledgements iii 1. Introduction 1 2. Climatic and Soil Requirements 1 3. Recommended Varieties 1 4. Recommendation Management Practices 3 5. Crop Protection 4 6. Harvesting 8 7.. Post-Harvest Handling and Processing 8 i Table of Contents Foreword ii Acknowledgements iii 1. Introduction 1 2. Climatic and Soil Requirements 1 3. Recommended Varieties 1 4. Recommendation Management Practices 3 5. Crop Protection 4 6. Harvesting 8 7.. Post-Harvest Handling and Processing 8 i Foreword Acknowledgements Zambia has the potential to produce sufficient food The Editorial Committee wishes to express its gratitude to the for its citizens and for export. Sorghum Research Team of Zambia Agriculture Research Institute for providing the technical information and invaluable advice. In order to ensure that good agricultural practices are employed by farmers, crop specific production The Zambia Agriculture Research Institute wishes to recognize the information should be made available to them. support provided by World Bank through the Agricultural Productivity Programme for Southern Africa- Zambia Project (APPSA-Zambia) Due to technological advances and the changing environmental and for financing the publication of this production guide. socio-economic conditions it became necessary to revise the first edition of the Sorghum Production Guide, which was published in 2002. This revised edition is meant to provide farmers and other stakeholders crop specific information in order to promote good agricultural practices and enhance productivity and production. -

A Description of Copulation in the Kori Bustard J Ardeotis Kori

i David C. Lahti & Robert B. Payne 125 Bull. B.O.C. 2003 123(2) van Someren, V. G. L. 1918. A further contribution to the ornithology of Uganda (West Elgon and district). Novitates Zoologicae 25: 263-290. van Someren, V. G. L. 1922. Notes on the birds of East Africa. Novitates Zoologicae 29: 1-246. Sorenson, M. D. & Payne, R. B. 2001. A single ancient origin of brood parasitism in African finches: ,' implications for host-parasite coevolution. Evolution 55: 2550-2567. 1 Stevenson, T. & Fanshawe, J. 2002. Field guide to the birds of East Africa. T. & A. D. Poyser, London. Sushkin, P. P. 1927. On the anatomy and classification of the weaver-birds. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. Bull. 57: 1-32. Vernon, C. J. 1964. The breeding of the Cuckoo-weaver (Anomalospiza imberbis (Cabanis)) in southern Rhodesia. Ostrich 35: 260-263. Williams, J. G. & Keith, G. S. 1962. A contribution to our knowledge of the Parasitic Weaver, Anomalospiza s imberbis. Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl. 82: 141-142. Address: Museum of Zoology and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of " > Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, U.S.A. email: [email protected]. 1 © British Ornithologists' Club 2003 I A description of copulation in the Kori Bustard j Ardeotis kori struthiunculus \ by Sara Hallager Received 30 May 2002 i Bustards are an Old World family with 25 species in 6 genera (Johnsgard 1991). ? Medium to large ground-dwelling birds, they inhabit the open plains and semi-desert \ regions of Africa, Australia and Eurasia. The International Union for Conservation | of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Animals lists four f species of bustard as Endangered, one as Vulnerable and an additional six as Near- l Threatened, although some species have scarcely been studied and so their true I conservation status is unknown. -

Namibia & the Okavango

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Biodiversity Observations

Biodiversity Observations http://bo.adu.org.za An electronic journal published by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town The scope of Biodiversity Observations consists of papers describing observations about biodiversity in general, including animals, plants, algae and fungi. This includes observations of behaviour, breeding and flowering patterns, distributions and range extensions, foraging, food, movement, measurements, habitat and colouration/plumage variations. Biotic interactions such as pollination, fruit dispersal, herbivory and predation fall within the scope, as well as the use of indigenous and exotic species by humans. Observations of naturalised plants and animals will also be considered. Biodiversity Observations will also publish a variety of other interesting or relevant biodiversity material: reports of projects and conferences, annotated checklists for a site or region, specialist bibliographies, book reviews and any other appropriate material. Further details and guidelines to authors are on this website. Lead Editor: Arnold van der Westhuizen – Paper Editor: Amour McCarthy and Les G Underhill INTERNET SEARCHING OF BIRD–BIRD ASSOCIATIONS: A CASE OF BEE-EATERS HITCHHIKING LARGE AFRICAN BIRDS Peter Mikula & Piotr Tryjanowski Recommended citation format: Mikula P, Tryjanowski P. 2016. Internet searching of bird–bird associations: A case of bee-eaters hitchhiking large African birds. Biodiversity Observations 7.80: 1–6. URL: http://bo.adu.org.za/content.php?id=273 Published online: 17 November 2016 – -

Katydid (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) Bio-Ecology in Western Cape Vineyards

Katydid (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) bio-ecology in Western Cape vineyards by Marcé Doubell Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Agricultural Sciences at Stellenbosch University Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology, Faculty of AgriSciences Supervisor: Dr P. Addison Co-supervisors: Dr C. S. Bazelet and Prof J. S. Terblanche December 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Summary Many orthopterans are associated with large scale destruction of crops, rangeland and pastures. Plangia graminea (Serville) (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) is considered a minor sporadic pest in vineyards of the Western Cape Province, South Africa, and was the focus of this study. In the past few seasons (since 2012) P. graminea appeared to have caused a substantial amount of damage leading to great concern among the wine farmers of the Western Cape Province. Very little was known about the biology and ecology of this species, and no monitoring method was available for this pest. The overall aim of the present study was, therefore, to investigate the biology and ecology of P. graminea in vineyards of the Western Cape to contribute knowledge towards the formulation of a sustainable integrated pest management program, as well as to establish an appropriate monitoring system. -

Nuweveld North Wind Farm

Nuweveld North Wind Farm Red Cap Nuweveld North (Pty) Ltd Avifaunal assessment October 2020 REPORT REVIEW & TRACKING Document title Nuweveld North Wind Farm - Avifaunal Impact study (Scoping Phase) Client name Patrick Killick Aurecon Status Final-for client Issue date October 2020 Lead author Jon Smallie – SACNASP 400020/06 WildSkies Ecological Services (Pty) Ltd 36 Utrecht Avenue, East London, 5241 Jon Smallie E: [email protected] C: 082 444 8919 F: 086 615 5654 2 Regulation GNR 326 of 4 December 2014, as amended 7 April 2017, Appendix 6 Section of Report (a) details of the specialist who prepared the report; and the expertise of that specialist to Appendix 5 compile a specialist report including a curriculum vitae ; (b) a declaration that the specialist is independent in a form as may be specified by the Appendix 6 competent authority; (c) an indication of the scope of, and the purpose for which, the report was prepared; Section 1.1 & 2 .1 an indication of the quality and age of base data used for the specialist report; Section 3 a description of existing impacts on the site, cumulative impacts of the proposed development Section 3.8 and levels of acceptable change; (d) the duration, date and season of the site investigation and the relevance of the season to Section 2.5 to 2.7 the outcome of the assessment; (e) a description of the methodology adopted in preparing the report or carrying out the Section 2 specialised process inclusive of equipment and modelling used; (f) details of an assessment of the specific identified sensitivity -

Singita Kruger National Park Wildlife Report August 2013

Singita Kruger National Park Lebombo & Sweni Lodges South Africa Wildlife Journal For the month of July, Two Thousand and Thirteen Temperature Rainfall Recorded Average Minimum: 12.3°C (54.1°F) For the period: 0mm Average Maximum: 27.0°C (80.7°F) For the year to date: 409.5mm Minimum recorded: 02.0°C (35.6°F) Maximum recorded: 34.0°C (93.4°F) Winter is definitely coming to an end Winter is always a productive time of the year for us on the concession, and this year has been as exciting as ever. A combination of the vegetation thinning out, and the permanent water sources have made for some spectacular, and consistent seasonal game viewing. Spring is upon us, and already some of the migratory birds have returned to this their southern destination - like southern yellow-billed kites and Wahlberg’s eagles. We now look forward to the first rains, with the promise of green colours, insect sounds and fresh smells, not to forget it's coming up to baby season! Coming of age It’s a harsh time in every young male lion's life, the day that they are seen as a threat to the dominant male and pushed into independence. When these young males reach puberty they are evicted from the pride and need to fend for themselves, this way ensuring there is no inbreeding within a pride. Pride dynamics dictate that all female members are related, being sisters, cousins or aunts to one another. Male eviction happens at roughly 2½ years old, the same age at which the mane becomes evident. -

Crop Protection Programme

CROP PROTECTION PROGRAMME Forecasting movements and breeding of the Red-billed Quelea bird in southern Africa and improved control strategies R7967 (ZA0467) FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT 1 January 2001 – 31 March 2003 Robert A. Cheke Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich July 2003 This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID (R7967 Crop Protection Programme). CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Background 2 Project Purpose 3 Research Activities 4 Activities for Output 1: A desk-based assessment of the environmental impacts of quelea control operations 4 Activities for Output 2: A preliminary analysis of the potential for developing a statistical medium term quelea seasonal forecasting model based on sea surface temperature (SST) data and atmospheric indicators 4 Activities for Output 3: Increased knowledge of the key relationships between environmental factors and quelea migrations and breeding activities 5 Activities for Output 4: An initial computer-based model for forecasting the timing and geographical distribution of quelea breeding activity in southern Africa developed in relation to control strategies of stakeholders 5 Outputs Report on Output 1 6 Report on Output 2 24 Report on Output 3 37 Report on Output 4 40 Conclusions and Impact 53 Outputs: supplementary comments 53 Contribution of Outputs to Developmental Impact 53 Dissemination Outputs 54 Acknowledgements 56 Biometrician’s letter 57 2 Executive Summary The project sought to improve the livelihoods of small-scale farmers in semi-arid areas of southern Africa, where their cereal crops are threatened by the Red-billed Quelea bird, and thus contribute to reductions in poverty. -

Indigenous Knowledge and Climate Change: Insights from Muzarabani, Zimbabwe

Indigenous Knowledge and Climate Change: Insights from Muzarabani, Zimbabwe by Nelson Chanza Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Geography Faculty of Science, Promoter: Dr Anton H. de Wit December, 2014 Dedication To my mother, Thokozile (Thokozayi). It was on one of the days in 2006 when we were busy weeding a dry maize field in the village. We had gone for three solid weeks without a single drop of rainfall, a situation that you described as peculiar. By that time, I did not figure it that you were referring to observable changes in the local climate system. Vividly, I can remember that on the same evening, you accurately predicted that the eastern-Mozambican current we experienced signalled the coming of rainfall in the next few hours. Amazingly, we received heavy downpours on the same night. My worry is that this knowledge will be lost as your generation vanishes. In recognition of your invaluable knowledge, I dedicate this thesis to you. ii Acknowledgements My two solid years of family detachment have proven beyond doubt that my prudent wife, Nyasha is a gift from God. She defied all the odds to make sure that our kids Tabitha, Angel and Prophecy received adequate parental care. In particular, she braved the demanding questions that our son incessantly pressed concerning his father’s whereabouts – Dadie varipi mama? Vanouya rini? Vanodii kuuya kumba? Her diligent support made this output possible. An expression of gratitude goes to Dr Anton de Wit for his thoughtful comments and guidance towards the successful production of this thesis. -

Namibia's Etosha Pan & Skeleton Coast

Namibia's Etosha Pan & Skeleton Coast Naturetrek Tour Report 30 October - 15 November 2015 Black Rhinoceros Elephant Family Flamingoes at Walvis Bay The desert Report compiled by Rob Mileto Images courtesy of Ingrid William Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Namibia's Etosha Pan & Skeleton Coast Tour Participants: Rob Mileto, Festus Mbinga & Franco Morao (leaders) and 12 Naturetrek clients Day 1 Friday 30th October London Heathrow to Johannesburg We all met up, mostly at the gate, for an uneventful overnight flight to Johannesburg in our double-decker plane Day 2 Saturday 31st October Johannesburg to Namib Grens Farm (via Windhoek) Weather: hot and sunny. The bleary but keen-eyed spotted our first southern African bird, a Rock Martin, from the Johannesburg airport terminal building. After a welcome coffee or two, a further short flight over the Kalahari brought us to Windhoek. Here we met out local guides, Festus and Franco, and were soon aboard our extended Land Rovers that were to be our transport and ‘hides’ for the next two weeks. Then we were off. After passing through Windhoek, we were soon out in the wilds and spotting lots of new birds and mammals like Chacma Baboon, Springbok, Cape Starling, Southern Yellow-billed Hornbill, White- backed Mousebird, Pale Chanting Goshawk and Ostrich. All these distractions meant that we arrived at Namib Grens after dark. The bungalows here are literally built around granite boulders which form some of the walls, and after a hearty farm dinner we retired to our beds amongst the rocks – one complete with a Rock Hyrax stuck in the bath! Day 3 Sunday 1st November Namib Grens to Kulala Weather: hot and sunny. -

Biomass Power Project Invertebrates Scoping Level

Biomass Power Project Invertebrates Scoping level John Irish 21 June 2017 Biodata Consultancy cc P.O. Box 30061, Windhoek, Namibia [email protected] 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................3 2 Approach to study..............................................................................................................3 2.1 Terms of reference..........................................................................................................3 2.2 Methodology...................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Literature survey..........................................................................................................3 2.2.2 Site visits......................................................................................................................5 3 Limitations and Assumptions.............................................................................................5 4 Legislative context..............................................................................................................6 4.1 Applicable laws and policies...........................................................................................6 5 Results...............................................................................................................................7 5.1 Raw diversity...................................................................................................................7 -

Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 1 Josh Engel

Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 1 Josh Engel Photos: Josh Engel, [[email protected]] Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History and Tropical Birding Tours [www.tropicalbirding.com] Produced by: Tyana Wachter, R. Foster and J. Philipp, with the support of Connie Keller and the Mellon Foundation. © Science and Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [[email protected]] [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org/guides] Rapid Color Guide #584 version 1 01/2015 1 Struthio camelus 2 Pelecanus onocrotalus 3 Phalacocorax capensis 4 Microcarbo coronatus STRUTHIONIDAE PELECANIDAE PHALACROCORACIDAE PHALACROCORACIDAE Ostrich Great white pelican Cape cormorant Crowned cormorant 5 Anhinga rufa 6 Ardea cinerea 7 Ardea goliath 8 Ardea pupurea ANIHINGIDAE ARDEIDAE ARDEIDAE ARDEIDAE African darter Grey heron Goliath heron Purple heron 9 Butorides striata 10 Scopus umbretta 11 Mycteria ibis 12 Leptoptilos crumentiferus ARDEIDAE SCOPIDAE CICONIIDAE CICONIIDAE Striated heron Hamerkop (nest) Yellow-billed stork Marabou stork 13 Bostrychia hagedash 14 Phoenicopterus roseus & P. minor 15 Phoenicopterus minor 16 Aviceda cuculoides THRESKIORNITHIDAE PHOENICOPTERIDAE PHOENICOPTERIDAE ACCIPITRIDAE Hadada ibis Greater and Lesser Flamingos Lesser Flamingo African cuckoo hawk Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 2 Josh Engel Photos: Josh Engel, [[email protected]] Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History and Tropical Birding Tours [www.tropicalbirding.com] Produced by: Tyana Wachter, R. Foster and J. Philipp,