Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Psychological Operationisms at Harvard: Skinner, Boring, And

[Forthcoming in Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences] Psychological operationisms at Harvard: Skinner, Boring, and Stevens Sander Verhaegh Tilburg University Abstract: Contemporary discussions about operational definition often hark back to Stanley Smith Stevens’ classic papers on psychological operationism (1935ab). Still, he was far from the only psychologist to call for conceptual hygiene. Some of Stevens’ direct colleagues at I would like to thank Julie Vargas, anonymous referees for the Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, and the staff at the Harvard University Archives for their help with this project. Drafts of this paper were presented at the 2019 conference of the History of Science Society (Utrecht University) and the 2019 conference of the Canadian Society for the History and Philosophy of Science (University of British Columbia). I would like to thank the audiences at both events for their valuable suggestions. This research is funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (grant 275–20–064). My archival research was funded by a Kristeller-Popkin Travel Fellowship from the Journal of the History of Philosophy, by a Rodney G. Dennis Fellowship in the Study of Manuscripts from Houghton Library, and a travel grant from the Evert Willem Beth Foundation. Correspondence concerning this paper should be addressed to Tilburg University, Department of Philosophy, Warandelaan 2, 5037AB, Tilburg, The Netherlands or to [email protected]. 1 Harvard⎯ most notably B. F. Skinner and E. G. Boring⎯ were also actively applying Bridgman’s conceptual strictures to the study of mind and behavior. In this paper, I shed new light on the history of operationism by reconstructing the Harvard debates about operational definition in the years before Stevens published his seminal articles. -

Prime Numbers and Implication Free Reducts of Mvn-Chains.Pdf

SYSMICS2019 Syntax Meets Semantics Amsterdam, The Netherlands 21-25 January 2019 Institute for Logic, Language and Computation University of Amsterdam SYSMICS 2019 The international conference “Syntax meet Semantics 2019” (SYSMICS 2019) will take place from 21 to 25 January 2019 at the University of Amsterdam, The Nether- lands. This is the closing conference of the European Marie Sk lodowska-Curie Rise project Syntax meets Semantics – Methods, Interactions, and Connections in Sub- structural logics, which unites more than twenty universities from Europe, USA, Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, Australia, Japan, and Singapore. Substructural logics are formal reasoning systems that refine classical logic by weakening structural rules in a Gentzen-style sequent calculus. Traditionally, non- classical logics have been investigated using proof-theoretic and algebraic methods. In recent years, combined approaches have started to emerge, thus establishing new links with various branches of non-classical logic. The program of the SYSMICS conference focuses on interactions between syntactic and semantic methods in substructural and other non-classical logics. The scope of the conference includes but is not limited to algebraic, proof-theoretic and relational approaches towards the study of non-classical logics. This booklet consists of the abstracts of SYSMICS 2019 invited lectures and contributed talks. In addition, it also features the abstract of the SYSMICS 2019 Public Lecture, on the interaction of logic and artificial intelligence. We thank all authors, members of the Programme and Organising Committees and reviewers of SYSMICS 2019 for their contribution. Apart from the generous financial support by the SYSMICS project, we would like to acknowledge the sponsorship by the Evert Willem Beth Foundation and the Association for Symbolic Logic. -

![Arxiv:1803.01386V4 [Math.HO] 25 Jun 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2691/arxiv-1803-01386v4-math-ho-25-jun-2021-712691.webp)

Arxiv:1803.01386V4 [Math.HO] 25 Jun 2021

2009 SEKI http://wirth.bplaced.net/seki.html ISSN 1860-5931 arXiv:1803.01386v4 [math.HO] 25 Jun 2021 A Most Interesting Draft for Hilbert and Bernays’ “Grundlagen der Mathematik” that never found its way into any publi- Working-Paper cation, and 2 CVof Gisbert Hasenjaeger Claus-Peter Wirth Dept. of Computer Sci., Saarland Univ., 66123 Saarbrücken, Germany [email protected] SEKI Working-Paper SWP–2017–01 SEKI SEKI is published by the following institutions: German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI GmbH), Germany • Robert Hooke Str.5, D–28359 Bremen • Trippstadter Str. 122, D–67663 Kaiserslautern • Campus D 3 2, D–66123 Saarbrücken Jacobs University Bremen, School of Engineering & Science, Campus Ring 1, D–28759 Bremen, Germany Universität des Saarlandes, FR 6.2 Informatik, Campus, D–66123 Saarbrücken, Germany SEKI Editor: Claus-Peter Wirth E-mail: [email protected] WWW: http://wirth.bplaced.net Please send surface mail exclusively to: DFKI Bremen GmbH Safe and Secure Cognitive Systems Cartesium Enrique Schmidt Str. 5 D–28359 Bremen Germany This SEKI Working-Paper was internally reviewed by: Wilfried Sieg, Carnegie Mellon Univ., Dept. of Philosophy Baker Hall 161, 5000 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15213 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: https://www.cmu.edu/dietrich/philosophy/people/faculty/sieg.html A Most Interesting Draft for Hilbert and Bernays’ “Grundlagen der Mathematik” that never found its way into any publication, and two CV of Gisbert Hasenjaeger Claus-Peter Wirth Dept. of Computer Sci., Saarland Univ., 66123 Saarbrücken, Germany [email protected] First Published: March 4, 2018 Thoroughly rev. & largely extd. (title, §§ 2, 3, and 4, CV, Bibliography, &c.): Jan. -

(0) 625307185 Home A

Work address: University College Groningen, Hoendiepskade 23/24, NL-9718 BG Groningen, The Netherlands, +31 (0) 625307185 Home address: ‘t Olde Hof 43, NL-9951JX Winsum, The Netherlands Dr. Dr. Simon Friederich born 30/08/1981 in Heidelberg, Germany http://simonfriederich.eu Email: s.m.friederich @ rug.nl AREAS OF RESEARCH General philosophy of science, philosophy of physics Philosophy of mathematics Epistemology AREAS OF COMPETENCE Philosophy of mind; effective altruism EDUCATION 2019 Habilitation (German qualification for full professorship) in philosophy, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany 2014 PhD in philosophy, Institute for Philosophy, University of Bonn, Germany; grade: “summa cum laude” 2010 PhD in physics, Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Heidelberg, Germany; grade: “magna cum laude” 2008 Magister in philosophy Philosophisches Seminar, University of Göttingen, Germany; grade: “with distinction” 2007 Diploma in physics Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Göttingen, Germany; grade: “very good” CURRENT POSITION Since September 2019 Associate professor of philosophy of science, University of Groningen, University College Groningen (UCG) and Faculty of Philosophy, The Netherlands, Interim Academic Director of Humanities at UCG October 2014 – August 2018, Assistant professor of philosophy of science, University of Groningen, University College Groningen and Faculty of Philosophy, The Netherlands In addition, since August 2015, external member of the Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy (MCMP) PREVIOUS POSITIONS 2012 – 2014 substituting for a full professorship in theoretical philosophy, University of Göttingen 2011 – 2012 PostDoc at University of Wuppertal University, research collaboration “Epistemology of the Large Hadron Collider”, funded by the German Academic Foundation (DFG) RESEARCH VISITS July 2019 visiting scholar at the Rotman Institute of Philosophy, University of Western Ontario (Canada) Host: Prof. -

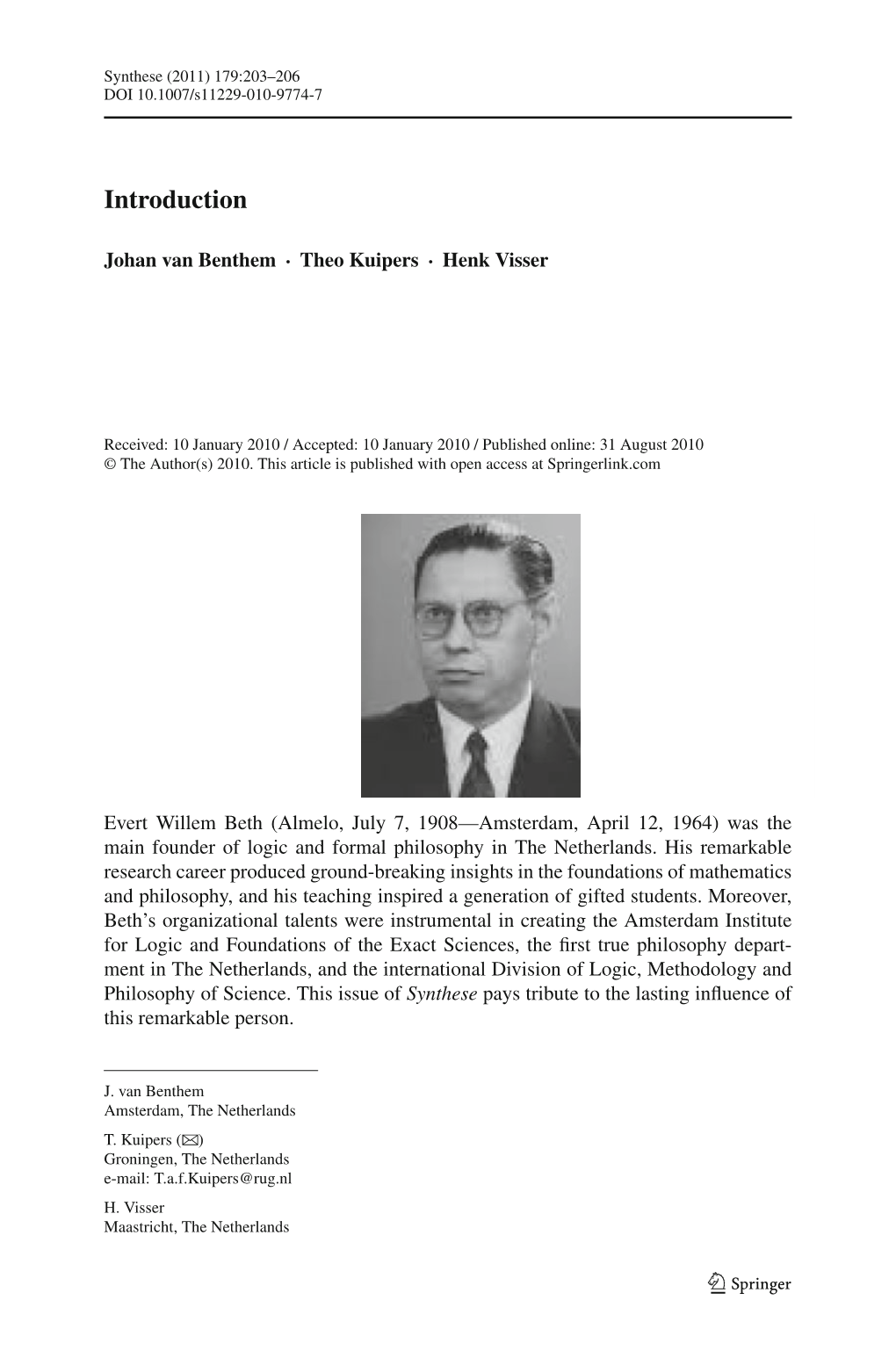

EVERT WILLEM BETH's SCIENTIFIC PHILOSOPHY 1. Introduction

EVERT WILLEM BETH'S SCIENTIFIC PHILOSOPHY Miriam FRANCHELLA Universita degli Studi, Milano 1. Introduction The Dutch man Evert Willem Beth (1908-1964) is famous for his contributions to logic. It is also known that he was a philosopher and became interested in logic quite late in his life. Still, the aspects of his philosophical reflections and the details of its development are almost unknown. He himself gave some hints for ordering his pro duction. 1 He divided it into four periods: the neo-kantian, the antikantian, the antiirrationalist, the logical one. Within this frame work, it is possible to individuate a core around which Beth devel oped his reflections: it is the interplay betwe~n philosophy and the sciences. In effect, his philosophical reflections were always linked to the sciences in two ways: firstly, because he steadily checked his philosophical ideas against the current situation in foundational re search; second, because he occupied himself with the general ques tion of the relationships between philosophy and the sciences. We are going to analyse these aspects in detail. 2. The role of intuition: thinking ofKant At the very beginning of his work Beth was convinced that intuitionism was the only acceptable foundational school. He con sidered logicism as "out" at that period. The other two positions - formalism and intuitionism - appealed both to intuition: 1. "Een terugblik" ("A retrospective view"), De Gids 123 (1960), 320-330; also in E.W. Beth, Door wetenshap tot wijsheid (Assen, van Gorcum 1964), 112-113. 222 intuitionism directly, in the construction of mathematics, while for malism only in the metamathematical analysis. -

The Proper Explanation of Intuitionistic Logic: on Brouwer's Demonstration

The proper explanation of intuitionistic logic: on Brouwer’s demonstration of the Bar Theorem Göran Sundholm, Mark van Atten To cite this version: Göran Sundholm, Mark van Atten. The proper explanation of intuitionistic logic: on Brouwer’s demonstration of the Bar Theorem. van Atten, Mark Heinzmann, Gerhard Boldini, Pascal Bourdeau, Michel. One Hundred Years of Intuitionism (1907-2007). The Cerisy Conference, Birkhäuser, pp.60- 77, 2008, 978-3-7643-8652-8. halshs-00791550 HAL Id: halshs-00791550 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00791550 Submitted on 24 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License The proper explanation of intuitionistic logic: on Brouwer’s demonstration of the Bar Theorem Göran Sundholm Philosophical Institute, Leiden University, P.O. Box 2315, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands. [email protected] Mark van Atten SND (CNRS / Paris IV), 1 rue Victor Cousin, 75005 Paris, France. [email protected] Der … geführte Beweis scheint mir aber trotzdem . Basel: Birkhäuser, 2008, 60–77. wegen der in seinem Gedankengange enthaltenen Aussagen Interesse zu besitzen. (Brouwer 1927B, n. 7)1 Brouwer’s demonstration of his Bar Theorem gives rise to provocative ques- tions regarding the proper explanation of the logical connectives within intu- itionistic and constructivist frameworks, respectively, and, more generally, re- garding the role of logic within intuitionism. -

Formal, Informal Or Anti-Logical? the Philosophy of the Logician Evert Willem Beth (1908-1964)

INFORMAL LOGIC XII. 1, Winter 1990 In the Service of Human Society: Formal, Informal or Anti-Logical? The Philosophy of the Logician Evert Willem Beth (1908-1964) E. M. BARTH Groningen University Introduction 1. Where does European argumentation theory come from? Proof as a social act The topic on which I have been asked to speak is, as far as I understood it, the Where does the highly amorphous field formal-informal divide in logic. Having called argumentation theory derive from? pondered about that task for a long time I There is, I believe, a certain difference be decided that concerning a weighing of the tween the United States on the one hand and pro's and con's of the two approaches I Europe and Canada on the other in this want to cut it short and to simply say: respect. Whereas in the United States the There ought to be formal logic, attuned departments of speech communication seem to human affairs; to have been very influential indeed, in There ought to be informal logic, attuned Europe argumentation theory derives from to human affairs; philosophy, and to a very large extent from logic-as in Canada. and once upon a time the twain shall meet. This fact is of considerable importance I do not accept the formal-informal for an understanding of the possibilities of, divide as a divide. That distinction ought and in, the field, as I shall try to show. Five to be played down. It is merely a question European philosophers at least from the of method-an interesting question, but not generation before us must be mentioned, at all a threatening one. -

E.W. Beth Als Logicus

E.W. Beth als logicus ILLC Dissertation Series 2000-04 For further information about ILLC-publications, please contact Institute for Logic, Language and Computation Universiteit van Amsterdam Plantage Muidergracht 24 1018 TV Amsterdam phone: +31-20-525 6051 fax: +31-20-525 5206 e-mail: [email protected] homepage: http://www.illc.uva.nl/ E.W. Beth als logicus Verbeterde electronische versie (2001) van: Academisch Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magni¯cus prof.dr. J.J.M. Franse ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Aula der Universiteit op dinsdag 26 september 2000, te 10.00 uur door Paul van Ulsen geboren te Diemen Promotores: prof.dr. A.S. Troelstra prof.dr. J.F.A.K. van Benthem Faculteit Natuurwetenschappen, Wiskunde en Informatica Universiteit van Amsterdam Plantage Muidergracht 24 1018 TV Amsterdam Copyright c 2000 by P. van Ulsen Printed and bound by Print Partners Ipskamp. ISBN: 90{5776{052{5 Ter nagedachtenis aan mijn vader v Inhoudsopgave Dankwoord xi 1 Inleiding 1 2 Levensloop 11 2.1 Beginperiode . 12 2.1.1 Leerjaren . 12 2.1.2 Rijpingsproces . 14 2.2 Universitaire carriere . 21 2.2.1 Benoeming . 21 2.2.2 Geleerde genootschappen . 23 2.2.3 Redacteurschappen . 31 2.2.4 Beth naar Berkeley . 32 2.3 Beth op het hoogtepunt van zijn werk . 33 2.3.1 Instituut voor Grondslagenonderzoek . 33 2.3.2 Oprichting van de Centrale Interfaculteit . 37 2.3.3 Logici en historici aan Beths leiband . -

Towards an Account of the Present Paradigm Conflict in the Development of Linguistics*

Towards an Account of the Present Paradigm Conflict in the Development of Linguistics* By Taki Bremmers 3853500 BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University Supervisor: Koen Sebregts Second Reader: Rick Nouwen November 2014 ____________________________ * I would like to thank my supervisor, Koen Sebregts, for motivating me and for carefully evaluating my work, as well as my friends and family, for supporting me. BA Thesis Taki Bremmers, November 2014 2 Abstract This thesis provides an account of the present linguistic paradigm conflict and its implications for the development of linguistics. In the light of Kuhn’s and Laudan’s respective theories of scientific progress, this thesis reflects upon the recent past, the present and the future of the linguistic field. The application of Kuhn’s theory to the current state of affairs in linguistics as described by Scholz, Pelletier, and Pullum suggests that the linguistic field is constituted upon three paradigms: Essentialism, Emergentism, and Externalism. These conflicting paradigms can be traced back to distinctive scientific traditions associated with Chosmky, Sapir, and Bloomfield, respectively. From the base of these past developments and the present situation, the future possibilities of linguistics can be inventoried: (1) linguistics may remain a pre- scientific discipline, (2) the linguistic paradigm conflict may persist, (3) the respective paradigms may be reconciled, or (4) a scientific revolution may take place. None of these scenarios can be precluded on the grounds of philosophical reflection. In reference to Kuhn’s and Laudan’s respective theories, it can, however, be argued that the linguistic field might be moved forward by promoting and evaluating debates between adherents of different paradigms. -

Intuitionistic Completeness of First-Order Logic with Respect to Uniform Evidence Semantics

Intuitionistic Completeness of First-Order Logic Robert Constable and Mark Bickford October 15, 2018 Abstract We establish completeness for intuitionistic first-order logic, iFOL, showing that a formula is provable if and only if its embedding into minimal logic, mFOL, is uniformly valid under the Brouwer Heyting Kolmogorov (BHK) semantics, the intended semantics of iFOL and mFOL. Our proof is intuitionistic and provides an effective procedure Prf that converts uniform minimal evidence into a formal first-order proof. We have implemented Prf. Uniform validity is defined using the intersection operator as a universal quantifier over the domain of discourse and atomic predicates. Formulas of iFOL that are uniformly valid are also intuitionistically valid, but not conversely. Our strongest result requires the Fan Theorem; it can also be proved classically by showing that Prf terminates using K¨onig’s Theorem. The fundamental idea behind our completeness theorem is that a single evidence term evd wit- nesses the uniform validity of a minimal logic formula F. Finding even one uniform realizer guarantees validity because Prf(F,evd) builds a first-order proof of F, establishing its uniform validity and providing a purely logical normalized realizer. We establish completeness for iFOL as follows. Friedman showed that iFOL can be embedded in minimal logic (mFOL) by his A-transformation, mapping formula F to F A. If F is uniformly valid, then so is F A, and by our completeness theorem, we can find a proof of F A in minimal logic. Then we intuitionistically prove F from F F alse, i.e. by taking False for A and for ⊥ of mFOL. -

Computability and Analysis: the Legacy of Alan Turing

Computability and analysis: the legacy of Alan Turing Jeremy Avigad Departments of Philosophy and Mathematical Sciences Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA [email protected] Vasco Brattka Faculty of Computer Science Universit¨at der Bundeswehr M¨unchen, Germany and Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics University of Cape Town, South Africa and Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences Cambridge, United Kingdom [email protected] October 31, 2012 1 Introduction For most of its history, mathematics was algorithmic in nature. The geometric claims in Euclid’s Elements fall into two distinct categories: “problems,” which assert that a construction can be carried out to meet a given specification, and “theorems,” which assert that some property holds of a particular geometric configuration. For example, Proposition 10 of Book I reads “To bisect a given straight line.” Euclid’s “proof” gives the construction, and ends with the (Greek equivalent of) Q.E.F., for quod erat faciendum, or “that which was to be done.” arXiv:1206.3431v2 [math.LO] 30 Oct 2012 Proofs of theorems, in contrast, end with Q.E.D., for quod erat demonstran- dum, or “that which was to be shown”; but even these typically involve the construction of auxiliary geometric objects in order to verify the claim. Similarly, algebra was devoted to developing algorithms for solving equa- tions. This outlook characterized the subject from its origins in ancient Egypt and Babylon, through the ninth century work of al-Khwarizmi, to the solutions to the quadratic and cubic equations in Cardano’s Ars Magna of 1545, and to Lagrange’s study of the quintic in his R´eflexions sur la r´esolution alg´ebrique des ´equations of 1770. -

Abraham Robinson 1918–1974

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ABRAHAM ROBINSON 1918–1974 A Biographical Memoir by JOSEPH W. DAUBEN Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs, VOLUME 82 PUBLISHED 2003 BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. Courtesy of Yale University News Bureau ABRAHAM ROBINSON October 6, 1918–April 11, 1974 BY JOSEPH W. DAUBEN Playfulness is an important element in the makeup of a good mathematician. —Abraham Robinson BRAHAM ROBINSON WAS BORN on October 6, 1918, in the A Prussian mining town of Waldenburg (now Walbrzych), Poland.1 His father, Abraham Robinsohn (1878-1918), af- ter a traditional Jewish Talmudic education as a boy went on to study philosophy and literature in Switzerland, where he earned his Ph.D. from the University of Bern in 1909. Following an early career as a journalist and with growing Zionist sympathies, Robinsohn accepted a position in 1912 as secretary to David Wolfson, former president and a lead- ing figure of the World Zionist Organization. When Wolfson died in 1915, Robinsohn became responsible for both the Herzl and Wolfson archives. He also had become increas- ingly involved with the affairs of the Jewish National Fund. In 1916 he married Hedwig Charlotte (Lotte) Bähr (1888- 1949), daughter of a Jewish teacher and herself a teacher. 1Born Abraham Robinsohn, he later changed the spelling of his name to Robinson shortly after his arrival in London at the beginning of World War II. This spelling of his name is used throughout to distinguish Abby Robinson the mathematician from his father of the same name, the senior Robinsohn.