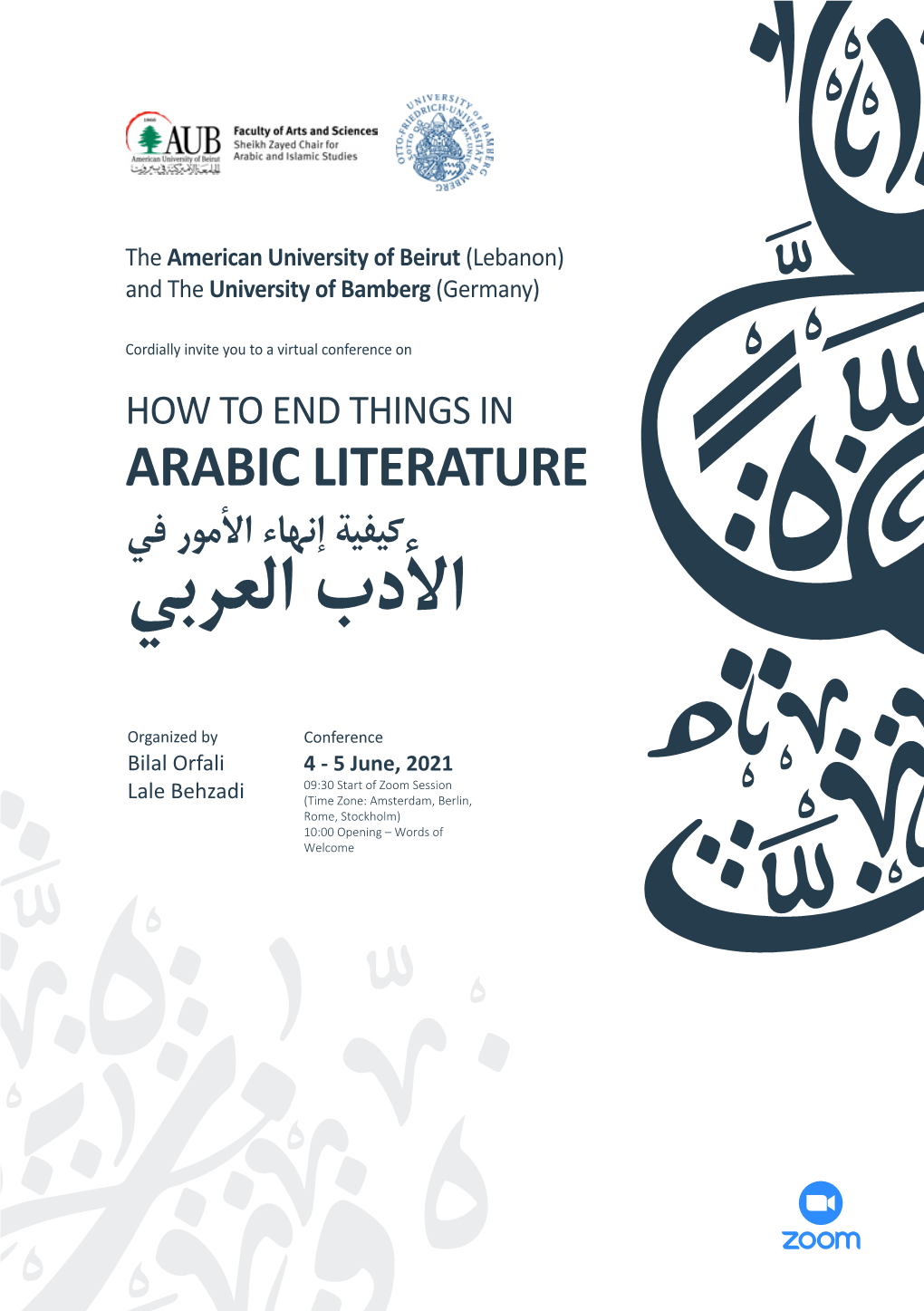

Arabic Literature كيفية إنهاء األمور في األدب العربي

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Palestinian Refugee Camps: Case Studies from Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine

The Atkin Paper Series Women in Palestinian Refugee Camps: Case Studies from Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine Manar Faraj ICSR Atkin Fellow June 2015 About the Atkin Paper Series To be a refugee is hard, but to be a woman and a refugee is the hardest Thanks to the generosity of the Atkin Foundation, the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) offers young leaders from Israel of all and the Arab world the opportunity to come to London for a period of four months. The purpose of the fellowship is to provide young leaders from Israel and the Arab he aim of this paper is to take the reader on a journey into the lived world with an opportunity to develop their ideas on how to further peace and experiences of Palestinian refugee women, in several stages. First, I offer understanding in the Middle East through research, debate and constructive dialogue Tan introduction to the historical roots and struggles of Palestinian refugee in a neutral political environment. The end result is a policy paper that will provide a women. This is followed by case studies drawn from my field research in refugee deeper understanding and a new perspective on a specific topic or event. camps in Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan. The third part of the paper includes recommendations for improving the participation of refugee women in the social Author and political arenas of these refugee camps. Three main questions have driven the Manar Faraj is from the Dhiesheh Refugee Camp, Bethlehem, Palestine. She is research for this paper: What is the role of women in the refugee camps? What currently a PhD candidate at Jena Univserity. -

Militia Politics

INTRODUCTION Humboldt – Universität zu Berlin Dissertation MILITIA POLITICS THE FORMATION AND ORGANISATION OF IRREGULAR ARMED FORCES IN SUDAN (1985-2001) AND LEBANON (1975-1991) Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil) Philosophische Fakultät III der Humbold – Universität zu Berlin (M.A. B.A.) Jago Salmon; 9 Juli 1978; Canberra, Australia Dekan: Prof. Dr. Gert-Joachim Glaeßner Gutachter: 1. Dr. Klaus Schlichte 2. Prof. Joel Migdal Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 18.07.2006 INTRODUCTION You have to know that there are two kinds of captain praised. One is those who have done great things with an army ordered by its own natural discipline, as were the greater part of Roman citizens and others who have guided armies. These have had no other trouble than to keep them good and see to guiding them securely. The other is those who not only have had to overcome the enemy, but, before they arrive at that, have been necessitated to make their army good and well ordered. These without doubt merit much more praise… Niccolò Machiavelli, The Art of War (2003, 161) INTRODUCTION Abstract This thesis provides an analysis of the organizational politics of state supporting armed groups, and demonstrates how group cohesion and institutionalization impact on the patterns of violence witnessed within civil wars. Using an historical comparative method, strategies of leadership control are examined in the processes of organizational evolution of the Popular Defence Forces, an Islamist Nationalist militia, and the allied Lebanese Forces, a Christian Nationalist militia. The first group was a centrally coordinated network of irregular forces which fielded ill-disciplined and semi-autonomous military units, and was responsible for severe war crimes. -

Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon

Islamism in the diaspora: Palestinian refugees in Lebanon Are Knudsen WP 2003: 10 Islamism in the diaspora: Palestinian refugees in Lebanon Are Knudsen WP 2003: 10 Chr. Michelsen Institute Development Studies and Human Rights CMI Reports This series can be ordered from: Chr. Michelsen Institute P.O. Box 6033 Postterminalen, N-5892 Bergen, Norway Tel: + 47 55 57 40 00 Fax: + 47 55 57 41 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.cmi.no Price: NOK 50 ISSN 0805-505X ISBN 82-8062-060-5 This report is also available at: www.cmi.no/public/public.htm Indexing terms Islam Refugees Palestinians Lebanon Project title Muwatin-CMI Research Co-operation Project number 22010 Contents INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... 1 PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN LEBANON: A BRIEF HISTORY.............................................. 2 REFUGEE CAMPS ...................................................................................................................................... 3 PALESTINIAN IDENTITY ....................................................................................................................... 5 LEBANESE HOSTS ..................................................................................................................................... 6 LEBANESE IS LAMISM............................................................................................................................. 9 MAINSTREAM ...........................................................................................................................................10 -

Syria Barometer Survey: Opinions About War in Syria and About Radical Action

Syria Barometer Survey: Opinions about War in Syria and about Radical Action Report to the Office of University Programs, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security June 2016 National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence Led by the University of Maryland 8400 Baltimore Ave., Suite 250 • College Park, MD 20742 • 301.405.6600 www.start.umd.edu National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence About This Report The authors of this report are Sophia Moskalenko, Bryn Mawr College, and Clark McCauley, Bryn Mawr Colelge. Questions about this report should be directed to Sophia Moskalenko at [email protected] and Clark McCauley at [email protected]. This report is part of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) project, “Changing Dynamics in the Levant,” led by Clark McCauley, Bryn Mawr College. This research was supported by the Office of University Programs, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security through Award 2012-ST-061-CS0001-04-AMENDMENT 6. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security or START. About START The National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) is supported in part by the Science and Technology Directorate of the U.S. -

Defence Forces Review 2016

Defence Forces Review Defence Forces 2016 Defence Forces Review 2016 Pantone 1545c Pantone 125c Pantone 120c Pantone 468c DF_Special_Brown Pantone 1545c Pantone 2965c Pantone Pantone 5743c Cool Grey 11c Vol 13 Vol Printed by the Defence Forces Printing Press Jn14102 / Sep 2016/ 2300 Defence Forces Review 2016 ISSN 1649 - 7066 Published for the Military Authorities by the Public Relations Branch at the Chief of Staff’s Division, and printed at the Defence Forces Printing Press, Infirmary Road, Dublin 7. © Copyright in accordance with Section 56 of the Copyright Act, 1963, Section 7 of the University of Limerick Act, 1989 and Section 6 of the Dublin University Act, 1989. The material contained in these articles are the views of the authors and do not purport to represent the official views of the Defence Forces. DEFENCE FORCES REVIEW 2016 PREFACE “By academic freedom I understand the right to search for truth and to publish and teach what one holds to be true. This right implies also a duty: one must not conceal any part of what one has recognized to be true. It is evident that any restriction on academic freedom acts in such a way as to hamper the dissemination of knowledge among the people and thereby impedes national judgment and action”. Albert Einstein As Officer in Charge of Defence Forces Public Relations Branch, it gives me great pleasure to be involved in the publication of the Defence Forces Review for 2016. This year’s ‘Review’ continues the tradition of past editions in providing a focus for intellectual debate within the wider Defence Community on matters of professional interest. -

Islam in Byzantium?

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation Seeing Eye to Eye: Islamic Universalism in the Roman and Byzantine Worlds, 7th to 10th Centuries Verfasser Olof Heilo angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Wien 2010 Studienblatt: A 092 383 Dissertationsgebiet: Byzantinistik und Neogräzistik Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Johannes Koder Acknowledgements I have been fortunate to simultaneously enjoy a number of benefits: thanks to the European Union, it was possible for me to embark upon this work in Austria while receiving financial support from Sweden, and in an era when boundless amounts of information are accessible everywhere, I could still enjoy a certain time for reflexion in the process of my studies. I am blessed with parents and siblings who not only share my interests in different ways, but who have actively supported me in all possible ways, and particularily during the two overtime years it took me to write a work I initially hoped would be finished in two years alone. From my years of studies in Lund and Copenhagen, I owe gratitude to profs. Karin and Jerker Blomqvist, prof. Bo Holmberg and dr. Lena Ambjörn, Eva Lucie Witte and Rasmus Christian Elling. Dr. Carl and Eva Nylander have inspired my pursuit of studies, whereas the kind advices of prof. Werner Seibt almost ten years ago encouraged me to go to Vienna. Dr. Roger Sages, whose Talmud readings I had the pleasure to attend in Lund, has been my mentor in philosophical matters; my godmother Barbro Brilioth has brought me contacts everywhere. I am particularily in debt to dr. Karin Ådahl at the Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul and to prof. -

Lebanon Assessment

Lebanon, Country Information http://194.203.40.90/ppage.asp?section=...itle=Lebanon%2C%20Country%20Information COUNTRY ASSESSMENT LEBANON April 2002 I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III HISTORY IV STATE STRUCTURES V HUMAN RIGHTS OVERVIEW VI HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VII HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B: PRINCIPLE POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: RELIGIOUS GROUPS ANNEX D: GLOSSARY ANNEX E: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT 1.01 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information & Policy Unit, Immigration & Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.02 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive; neither is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.03 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.04 It is intended to revise the assessment on a 6-monthly basis while the country remains 1 of 71 07/11/2002 5:31 PM Lebanon, Country Information http://194.203.40.90/ppage.asp?section=...itle=Lebanon%2C%20Country%20Information within the top 35 asylum producing countries in the United Kingdom. 1.05 The assessment will be placed on the Internet (http://www.ind.homeoffice.gov.uk). -

Militarization of Ethnic Conflict in Turkey, Israel

MILITARIZATION OF ETHNIC CONFLICT IN TURKEY, ISRAEL AND PAKISTAN by Murat Ulgul A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Summer 2015 © 2015 Murat Ulgul All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number: 3730202 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 3730202 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 MILITARIZATION OF ETHNIC CONFLICT IN TURKEY, ISRAEL AND PAKISTAN by Murat Ulgul Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Gretchen Bauer, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: ___________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: ___________________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have -

Palestinian Refugees from Syria

al majdalIssue No.56 (Autumn 2014) quarterly magazine of BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights PALESTINIAN REFUGEES FROM SYRIA: ONGOING NAKBA, ONGOING DISCRIMINATION BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency Get your Subscription to ABOUT THE MEANING OF al -Majdal and Refugee Rights is an independent, community- al-Majdal is a quarterly magazine of al-Majdal Today! based non-profit organization mandated to protect BADIL Resource Center that aims to raise al-Majdal is an Aramaic word meaning and promote the rights of Palestinian refugees and fortress. The town was known as internally displaced persons. Our vision, mission, public awareness and support for a just solution al-Majdal is Badil’s quarterly programs and relationships are defined by our to Palestinian residency and refugee issues. magazine, and an excellent Majdal Jad during the Canaanite Palestinian identity and the principles of international source of information on key period for the god of luck. Located in law, in particular international human rights law. We Electronic versions are available online at: issues relating to the cause the south of Palestine, al-Majdal was seek to advance the individual and collective rights of a thriving Palestinian city with some www.badil.org/al-majdal/ of Palestine in general, and the Palestinian people on this basis. 11,496 residents on the eve of the Palestinian refugee rights in 1948 Nakba. Majdalawis produced BADIL has consultative status with UN ECOSOC (a ISSN 1726-7277 particular. framework partnership agreement with UNHCR), a a wide variety of crops including oranges, grapes, olives and vegetables. member of the PHROC (Palestinian Human Rights PUBLISHED BY Organizations Council), PNGO (Palestinian NGO BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Palestinian residents of the town Network), BNC (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions owned 43,680 dunums of land. -

The Political Unification of the Israeli Army

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1984 The political unification of the Israeli Army Michael Uhry Newman Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Political History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Newman, Michael Uhry, "The political unification of the Israeli Army" (1984). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3581. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Michael Uhry Newman for the Master of Arts in History presented August 24, 1984. Title: The Political Unification of the Israeli Army. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Jon E. Mandaville I Dr. r:ia vid~ A. ' Horowitz Dr. Thomas M. P'oulsen The essay charts forty years of Zionist history to illuminate the ' remarkable evolution of Israel's unified, apolitical army and Israel's "democratic civil-military tradition," forged in the fires of opposing military styles, ideological rivalry, competing underground forces, war and civil war. During the years 1907-1919, the Yishuv acquired two different military traditions, the Pioneer-Soldier tradition and the Professional 2 tradition. During 1920-1931, the presence of the British Mandatory power and rising Arab Nationalist violence produced a third military tradition the "Underground," first developed by the early Hagana, woven into the fabric of the Socialist-Zionism. -

![Lebanon [2008] UKAIT 00014](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9940/lebanon-2008-ukait-00014-8719940.webp)

Lebanon [2008] UKAIT 00014

Asylum and Immigration Tribunal MM and FH (Stateless Palestinians – KK, IH, HE reaffirmed) Lebanon [2008] UKAIT 00014 THE IMMIGRATION ACTS Heard at Field House On 29 June 2007 Before Senior Immigration Judge Mather Senior Immigration Judge Nichols Mr J H Eames Between MM FH Appellants and SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT Respondent Representation : For the Appellant: Mr D Blum, Counsel, instructed by Knights Solicitors For the Respondent: Miss E Laing, Counsel, instructed by The Treasury Solicitors. i. The differential treatment of stateless Palestinians by the Lebanese authorities and the conditions in the camps does not reach the threshold to establish either persecution under the Geneva Convention, or serious harm under paragraph 339C of the Immigration Rules, or a breach of Articles 3 or 8 under the ECHR. ii. The differential treatment of Palestinians by the Lebanese authorities is not by reason of race but arises from their statelessness. iii. The decision in KK, IH, HE (Palestinians-Lebanon-camps) Jordan CG [2004] UKIAT 00293, is reaffirmed. © CROWN COPYRIGHT 2008 DETERMINATION AND REASONS 1. Both appellants in these appeals are stateless Palestinians from Lebanon. They both appealed on asylum and human rights grounds against a decision of the respondent to refuse to grant them asylum under paragraph 339 of HC 395. The appeals were both dismissed. The evidence of both appellants was found, for the most part, not to be credible. The sole issue in the appeals on which reconsideration has been ordered is whether or not the appellants as stateless Palestinians would suffer discrimination on return to Lebanon that would amount to persecution or breach their Article 3 or Article 8 rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (“the ECHR”). -

Chapter 1 — Becoming Poor: Deprivation and Religious Decline in Shī‘Ī Lebanon (1920-1960)

REBEL PREACHERS: THE MAKING OF ISLAMIC ACTIVISM IN SHĪ‘Ī LEBANON (1960-1985) A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Islamic Studies By Nabil Al-Hage Ali, M.A. Washington, DC July 7, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Nabil Al-Hage Ali All Rights Reserved ii REBEL PREACHERS: THE MAKING OF ISLAMIC ACTIVISM IN SHĪ‘Ī LEBANON (1960-1985) Nabil Al-Hage Ali, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Felicitas M. M. Opwis, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This study investigates the intellectual and organizational genesis of the Shī‘ī religious community that burgeoned in Lebanon in the 1970s. It demonstrates how several competing religious currents in the Shī‘ī community evolved through several overlapping phases of religious education, mobilization, revolutionization, and consolidation. Predominant academic opinions link the formation of new religious consciousness and new religious movements that succeeded the formation of Hizbullah in Shī‘ī Lebanon to Iran’s exportation of its “Islamic Revolution.” Not only does this study reopen the discussion on the transformation of forms of religiosity in Shī‘ī Lebanon, but it also elucidates the identity and origins of groups and ideas that constitute the contemporary Shī‘ī milieu that crystallized in the 1980s. This study, thus, offers a reconceptualization of present time orientations and positions in the religious field as products of an eventful past through analysis of several religious projects that appeared two full decades before the rise of Hizbullah. It looks at several religious paradigms that interacted in contexts of sectarianism, economic crises, and wars.