631 ROBERT and CHARLES Robert and I Were Sitting Beside His

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish Fauna of the Fitzroy River in the Kimberley Region of Western Australia - Including the Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Ngarinyin, Nyikina and Walmajarri Aboriginal Names

DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.22(2).2004.147-161 Records of the Westelll Allstralllll1 A//uselllll 22 ]47-]6] (2004). Fish fauna of the Fitzroy River in the Kimberley region of Western Australia - including the Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Ngarinyin, Nyikina and Walmajarri Aboriginal names J J 2 3 David L. Morgan , Mark G. Allen , Patsy Bedford and Mark Horstman 1 Centre for Fish & Fisheries Research, School of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia 6]50 KImberley Language Resource Centre, PO Box 86, Fitzroy Crossing, Western Australia 6765 'Kimberley Land Council, PO Box 2145, Broome Western Australia 6725 Abstract - This project surveyed the fish fauna of the Fitzroy River, one of Australia's largest river systems that remains unregulated, 'located in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. A total of 37 fish species were recorded in the 70 sites sampled. Twenty-three of these species are freshwater fishes (i.e. they complete their life-cycle in freshwater), the remainder being of estuarine or marine origin that may spend part of their life-cycle in freshwater. The number of freshwater species in the Fitzroy River is high by Australian standards. Three of the freshwater fish species recorded ar'e currently undescribed, and two have no formal common or scientific names, but do have Aboriginal names. Where possible, the English (common), scientific and Aboriginal names for the different speCIes of the river are given. This includes the Aboriginal names of the fish for the following five languages (Bunuba, Gooniyandi, Ngarinyin, Nyikina and Walmajarri) of the Fitzroy River Valley. The fish fauna of the river was shown to be significantly different between each of the lower, middle and upper reaches of the main channeL Furthermore, the smaller tributaries and the upper gorge country sites were significantly different to those in the main channel, while the major billabongs of the river had fish assemblages significantly different to all sites with the exception of the middle reaches of the river. -

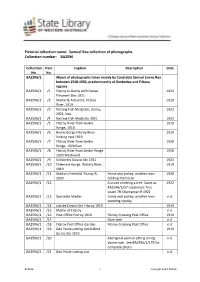

Collection Name: Samuel Rea Collection of Photographs Collection Number: BA2596

Pictorial collection name: Samuel Rea collection of photographs Collection number: BA2596 Collection Item Caption Description Date No. No. BA2596/1 Album of photographs taken mainly by Constable Samuel James Rea between 1918-1932, predominantly of Kimberley and Pilbara regions BA2596/1 /1 Fitzroy to Derby with Native 1921 Prisoners Dec 1921 BA2596/1 /2 Martin & A B Scott, Fitzroy 1919 River, 1919 BA2596/1 /3 Netting Fish Meda Stn, Derby, 1921 1921, Nov BA2596/1 /4 Netting Fish Meda Stn 1921 1921 BA2596/1 /5 Fitzroy River from Geikie 1919 Range, 1919 BA2596/1 /6 Geikie Gorge Fitzroy River 1919 looking east 1919 BA2596/1 /7 Fitzroy River from Geikie 1920 Range, 1920 East BA2596/1 /8 Fitzroy River from Geikie Range 1920 1920 Westward BA2596/1 /9 Kimberley Downs Stn 1921 1921 BA2596/1 /10 Telemere Gorge. Watery River, 1919 1919 BA2596/1 /11 Martin's Emerald. Fitzroy R, Horse and jockey, another man 1920 1920 holding the horse BA2596/1 /12 A snake climbing a tree. Same as 1922 BA2596/1/57 captioned: Tree snake 7ft Champman R 1922 BA2596/1 /13 Scarsdale Martin Horse and jockey, another man n.d. standing nearby BA2596/1 /14 Jubilee Downs Stn Fitzroy 1919 1919 BA2596/1 /15 Martin at Fitzroy n.d. BA2596/1 /16 Post Office Fitzroy 1919 Fitzroy Crossing Post Office 1919 BA2596/1 /17 Gum tree n.d. BA2596/1 /18 Fitzroy Post Office Garden Fitzroy Crossing Post Office n.d. BA2596/1 /19 Geo Poole cutting out bullock 1919 Go Go Stn 1919 BA2596/1 /20 Aboriginal woman sitting on log n.d. -

Prediction of Potentially Significant Fish Harvest Using Metrics of Accessibility in Northern Western Australia

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 97: 355–361, 2014 Prediction of potentially significant fish harvest using metrics of accessibility in northern Western Australia PAUL G CLOSE 1, REBECCA J DOBBS 1, TOM J RYAN 1, KARINA RYAN 2, PETER C SPELDEWINDE 1 & SANDY TOUSSAINT 1,3 1 Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management, The University of Western Australia, Albany, WA 6330, Australia 2 Western Australian Fisheries and Marine Research Laboratories, Department of Fisheries, Hillarys, WA 6025, Australia 3 Anthropology and Sociology, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia [email protected] Management of freshwater fisheries in northern Australia faces challenges that combine Aboriginal and recreational harvests, intermittent river flows and remote, expansive management jurisdictions. Using relationships between fishing pressure (vis-à-vis ‘accessibility’) and the abundance of fish species targeted by Aboriginal and recreational fishers (derived from the Fitzroy River, Western Australia), the potential fishing pressure in subcatchments across the entire Kimberley region was assessed. In addition to the Fitzroy and Ord River, known to experience substantial fishing pressure, this assessment identified that subcatchments in the Lennard and King Edward river basins were also likely to experience relatively high fishing activity. Management of freshwater fisheries in the Kimberley region prioritises aquatic assets at most risk from the potential impact of all aquatic resource use and employs -

Indian O Cean Western Australia

136 333. e f f or call i l 7044 c P706000 d 479 9 e 08 R avis.com.au visitor mapto visitor Australia Western Your free free Your h t r e Competitive Rates Competitive and utes trucks cars, Late-model Earn Qantas Points holiday voucher book a free Receive Please quote reference number quote reference Please P 08 9237 0022 • • • • AVIS GREAT RATES AND SERVICE RATES GREAT For more Perth locations, visit locations, Perth more For joining fee may apply. A Flyer program. subject to the terms & conditions of^Membership and points are the Qantas Frequent see Qantas.com/cars CT10737 points on car hire information about earning more For REGIONAL WA VISITOR CENTRES Broome 1460 Carnarvon 17 Albany Visitor Centre Karijini Visitor Centre 2151 738 Cervantes King George Falls A 221 York Street, Albany A Banjima Drive, Karijini 1420 227 966 Coral Bay P 08 6820 3700 National Park, Tom Price 1779 334 667 583 Denham W amazingalbany.com.au P 08 9189 8121 Kalumbaru W parks.dpaw.wa.gov.au/park/ 221 1616 2305 1557 1932 Derby Augusta Visitor Centre karijini 1374 368 1093 140 691 1527 Exmouth River A 75 Blackwood Avenue, Augusta Mitchell River 1933 482 259 708 435 2086 838 Geraldton National Park Drysdale River Berkeley P 08 9758 0166 Karratha Visitor Centre 1895 446 412 673 400 2049 802 167 Kalbarri National Park W margaretriver.com A De Witt Road , Karratha Mitchell Ord River 2644 1461 779 1624 1326 2797 1816 984 1073 Kalgoorlie 16 6Falls Nature Reserve P 08 9144 4600 Ord River 833 637 1334 586 961 986 555 1114 1078 1844 Karratha Prince Regent King Edward River -

Summary Wetland Sample Site

Summary of Wetland Sample Sites This table has a list of the sites from the Database where wetland sampling has been conducted. It also shows what type of sampling was carried out at each site. You can search for your site of interest by: 1. Filter the list by Data Source or Sampling Type (use the filter buttons) OR 2. Search for a site name using the Find tool (Ctrl + f). Note that even if your site is not listed here you can search for it on the database where you will find other useful information related to your site. -

98 KIMBERLEY I Have Only Once Kept a Diary in My Life and That Was

KIMBERLEY I have only once kept a diary in my life and that was during my time in Kimberley, and the extraordinary thing is that over the 50 years that have passed since that time it has remained in my possession. Keeping the diary on this one occasion was probably something to do with the stories Hedley had told me from Archibald Watson’s diaries only months before I went north. Sadly my diary makes very dull reading compared to those tales, but when I read it recently it did make my Kimberley days come alive for me again. The diary also played a part in my life many years later when I became interested in the Bradshaw paintings of Kimberley. My entries capture my reaction to meeting Aborigines for the first time and working with black people. It was not until WWII when the American army was billeted in England that most Britishers came in contact with black people. My first mass contact with a coloured race had been with the Zulu stevedores in Cape Town, when the ship had docked to load cargo on my voyage from England to Australia. The diary shows how my feelings about the Aborigines changed from fear to a paternal friendship. I read that I arrived in Perth on April 6th 1955 and stayed at the old Esplanade Hotel. What a superb old-fashioned Victorian hotel it was in those days! I am sure it has long since been pulled down; if so, what a shame! I was only in Perth long enough to meet the owner of Liveringa Station, Mr Forest, who I hoped would employ me. -

Fitzroy Valley Indigenous Cultural Values Study

FitzroyValleyIndigenousCultural ValuesStudy (apreliminaryassessment) SandyToussaint,PatrickSullivan,SarahYu,MervynMulartyJnr. CentreforAnthropologicalResearch, TheUniversityofWesternAustralia, Nedlands,WA,6009 ReportfortheWaterandRiversCommission 3PlainStreet,Perth,WA,6000 February2001 1.0 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 3.0. INTRODUCTION 5 3.1. TheFitzroyValleyIndigenousCulturalValuesStudy 5 3.2. Ethics,Protocol,Confidentiality 8 3.3. ResearchMethods,Process,PlacesVisited 9 3.4. StudyQualitiesandLimitations 11 3.5. ANoteonWordsandLanguageUse 13 3.6. StructureoftheReport 13 4.0. THEFITZROYVALLEY:ANOVERVIEW 14 4.1. LanguageGroupsandaffiliationstoLandandWater 14 4.2. Geography,Ecology,History 20 4.3. TextualandVisualRepresentationsofLandandWater(literature,paintings,postcards) 28 5.0. STUDYFINDINGS 36 5.1. APreliminaryAssessment 36 5.2. CulturalBeliefsandPractices 36 5.3. SocialandEconomicIssues 43 5.4. 'River'and'Desert'Cultures 50 5.5. EnvironmentalInterpretations 52 5.6. CulturalResponsibilitiesandAspirations 57 5.7. ConsequencesofWaterChangeoverTime 62 6.0. CONCLUSIONS 70 7.0. RECOMMENDATIONS 72 APPENDICES 75 8.1. PERSONSCONSULTED 75 8.2. PLACESVISITED 77 2 8.3. ADVICETOCOMMUNITIESANDORGANISATIONS 78 8.4.SAMPLELETTERS 79 8.5WORDLISTRELATINGTOWATERUSE 81 8.6DARBYNANGKIRINY’SSTORY 84 8.7GEOGRAPHICLOCATIONSOFWATERSITESINLOWERFITZROY/HANNAREA 86 8.8MAPSFROMRAPARAPAKULARRMARTUWARRA 88 9.0. BIBLIOGRAPHY(INCLUDINGREFERENCESCITEDINREPORT) 90 LISTOFMAPS 1. FitzroyValley,Kimberley,WesternAustralia p.6 2. PlacesNamedinReport p.10 3. LandandWaterLanguageAffiliations -

Australia Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Australia: Topographic maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific. Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage. Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one. Coverage of Australian States – All states held. The numbering of the maps represents a grid system. The first two letters, eg SD represent north-south with the second letter increasing south of the Equator. The next numbers, eg 56 represent east-west and increase from west to east. Index maps at bottom of page SC 52 Melville Island (NT) SC-52-16 SC 53 Coburg Penin (NT) SC-53-13 Junction Bay (NT) SC-53-14 Wessel Islands (NT) SC-53-15 Truant Island (NT) SC-53-16 SC 54 Daru (Q) SC-54-8 Thursday Island (Q) SC-54-11 Cape York (Q) SC-54-12 Jardine River (Q) SC-54-15 Orford Bay (Q) SC-54-16 SC 55 Maer (Q) SC-55-5 SD 51 Long Reef (WA) SD-51-08 Browse Island (WA) SD-51-11 Montague Sound (WA) SD-51-12 Camden Sound (WA) SD-51-15 Prince Regent (WA) SD-51-16 Page 1 of 22 Last updated May 2013 University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Australia: Topographic maps 1: 250,000 SD 52 Fog Bay (NT) SD-52-03 Darwin (NT) SD-52-04 Londonderry (WA) SD-52-05 Cape Scott (NT) SD-52-07 Pine Creek (NT) SD-52-08 Drysdale (WA) SD-52-09 Medusa Banks (WA) SD-52-10 Port Keats (NT) SD-52-11 Fergusson River (NT) SD-52-12 Ashton (WA) SD-52-13 Cambridge Gulf (WA) SD-52-14 Auvergne (NT) SD-52-15 -

Birds of the Kimberley Division, Western Australia

WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SPECIAL PUBLICATION No.ll Birds of the Kimberley Division, Western Australia by G.M. Slorr Perth 1980 World List Abbreviation: Spec. PubIs West. Aust. Mus. ISBN 0724481389 ISSN 0083 873X Cover: A Comb-crested Jacana drawn by Gaye Roberts. Published by the Western Australian Museum, Francis Street, Perth 6000, Western Australia. Phone 328 4411. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 7 List of Birds .................................... .. 9 Gazetteer ................................. .. 101 Index 105 5 INTRODUCTION Serventy and Whittell's excellent Birds of Western Australia (first published in 1948) excluded the many species found in Western Australia only in the Kimberley Division. The far north of the State thus remained the last terra incognita in Australia. The present paper fills this gap by providing informa tion on the distribution, ecological status, relative abundance, habitat preferences, movements and breeding season of Kimberley birds. Coverage is much the same as in my List of Northern Territory birds (1967, Spec. PubIs West. Aust. Mus. no. 4), List of Queensland birds (1973, Spec. PubIs West. Aust. Mus. no. 5) and Birds of the Northern Territory (1977, Spec. PubIs West. Aust. Mus. no. 7). An innovation is data on clutch size. The area covered by this paper is the Kimberley Land Division (Le. that part of Western Australia north of lat. 19°30'S) and the seas and islands of the adjacent continental shelf, including specks of land, such as Ashmore Reef, that are administered by the Commonwealth of Australia. Distribution is often given in climatic as well as geographic terms by referring to the subhumid zone (mean annual rainfall 100-150 cm), semiarid zone (50-100 cm) or arid zone (less than 50 cm). -

Water and Environment

Water and Environment STRATEGIC REVIEW OF THE SURFACE WATER MONITORING NETWORK REPORT Prepared for Department of Water Date of Issue 3 August 2009 Our Reference 1045/B1/005e STRATEGIC REVIEW OF THE SURFACE WATER MONITORING NETWORK REPORT Prepared for Department of Water Date of Issue 3 August 2009 Our Reference 1045/B1/005e STRATEGIC REVIEW OF THE SURFACE WATER MONITORING NETWORK REPORT Date Revision Description Revision A 28 April 2009 Draft Report for client review Revision B 05 June 2009 Amendments following client review Revision C 19 June 2009 Further amendments following client review Revision D 30 July 2009 Final inclusion of figures and formatting Revision E 3 August 2009 Final for release to client Name Position Signature Date Originator Glen Terlick Senior Hydrographer, 30/07/09 Department of Water Emma Neale Environmental 30/07/09 Consultant Reviewer Vince Piper Principal Civil/ Water 30/07/09 Resources Engineer Leith Bowyer Senior Hydrologist, 30/07/09 Department of Water Location Address Issuing Office Perth Suite 4, 125 Melville Parade, Como WA 6152 Tel: 08 9368 4044 Fax: 08 9368 4055 Our Reference 1045/B1/005e STRATEGIC REVIEW OF THE SURFACE WATER MONITORING NETWORK REPORT CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................1 1.1 Background ...................................................................................................1 1.2 State Water Strategy......................................................................................1 -

Lower Fitzroy River Groundwater Review

Lower Fitzroy River Groundwater Review A report prepared for Department of Water W.A. FINAL Version 15 May 2015 Lower Fitzroy River Groundwater Review 1 How to cite this report: Harrington, G.A. and Harrington, N.M. (2015). Lower Fitzroy River Groundwater Review. A report prepared by Innovative Groundwater Solutions for Department of Water, 15 May 2015. Disclaimer This report is solely for the use of Department of Water WA (DoW) and may not contain sufficient information for purposes of other parties or for other uses. Any reliance on this report by third parties shall be at such parties’ sole risk. The information in this report is considered to be accurate with respect to information provided by DoW at the time of investigation. IGS has used the methodology and sources of information outlined within this report and has made no independent verification of this information beyond the agreed scope of works. IGS assumes no responsibility for any inaccuracies or omissions. No indications were found during our investigations that the information provided to IGS was false. Innovative Groundwater Solutions Pty Ltd. 3 Cockle Court, Middleton SA 5213 Phone: 0458 636 988 ABN: 17 164 365 495 ACN: 164 365 495 Web: www.innovativegroundwater.com.au Email: [email protected] 15 May 2015 Lower Fitzroy River Groundwater Review 2 Executive Summary Water for Food is a Royalties for Regions initiative that aims to lift agricultural productivity and encourage capital investment in the agricultural sector in a number of regions across Western Australia. In the West Kimberley region, the lower Fitzroy River valley is seen as a priority area where water resources can be developed to support pastoral diversification. -

West Kimberley Place Report

WEST KIMBERLEY PLACE REPORT DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY ONE PLACE, MANY STORIES Located in the far northwest of Australia’s tropical north, the west Kimberley is one place with many stories. National Heritage listing of the west Kimberley recognises the natural, historic and Indigenous stories of the region that are of outstanding heritage value to the nation. These and other fascinating stories about the west Kimberley are woven together in the following description of the region and its history, including a remarkable account of Aboriginal occupation and custodianship over the course of more than 40,000 years. Over that time Kimberley Aboriginal people have faced many challenges and changes, and their story is one of resistance, adaptation and survival, particularly in the past 150 years since European settlement of the region. The listing also recognizes the important history of non-Indigenous exploration and settlement of the Kimberley. Many non-Indigenous people have forged their own close ties to the region and have learned to live in and understand this extraordinary place. The stories of these newer arrivals and the region's distinctive pastoral and pearling heritage are integral to both the history and present character of the Kimberley. The west Kimberley is a remarkable part of Australia. Along with its people, and ancient and surviving Indigenous cultural traditions, it has a glorious coastline, spectacular gorges and waterfalls, pristine rivers and vine thickets, and is home to varied and unique plants and animals. The listing recognises these outstanding ecological, geological and aesthetic features as also having significance to the Australian people. In bringing together the Indigenous, historic, aesthetic, and natural values in a complementary manner, the National Heritage listing of the Kimberley represents an exciting prospect for all Australians to work together and realize the demonstrated potential of the region to further our understanding of Australia’s cultural history.