Dalit and Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punjab's 26/11 Moment

JAIPUR l FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 27, 2020 l Pages 12 l 3.00 RNI NO. RAJENG/2019/77764 l Vol 2 l Issue No. 171 ECONOMIC RECOVERY STRONGER THAN HARYANA GOVERNMENT SETS UP A EXPECTED, BUT SURGE IN COVID CASES THREE-MEMBER COMMITTEE TO DRAFT P5 KEY RISK, SAYS RBI GOVERNOR DAS A LAW AGAINST ‘LOVE JIHAD’ P6 OUR EDITIONS: JAIPUR, AHMEDABAD & LUCKNOW 12°C - 25°C www.fi rstindia.co.in I www.fi rstindia.co.in/epaper/ I twitter.com/thefi rstindia I facebook.com/thefi rstindia I instagram.com/thefi rstindia CALAMITY TO CAPITAL SEIGE People wade through waterlogging after heavy rainfall lashed Chennai DILLI CHALO Members of various farmer organisations remove a barricade as they march towards Delhi during Police detain protestors during a protest in support of nationwide strike with the onset of cyclone Nivar, in Chennai. Delhi Chalo protest over the farm reform bills, at Punjab-Haryana border in Ambala on Thursday. —PHOTOS BY PTI by ten central trade unions against NDA, in Kolkata on Thursday. PM to visit Serum Ahmed Bhai laid to rest in Guj’s Badal calls farmers’ protest Institute, Bharat Biotech tomorrow Bharuch; Rahul attends funeral amid vaccine race Bharuch: Congress Punjab’s 26/11 moment leader Ahmed Patel was laid to rest in Bharuch, Amritsar/Ambala: Gujarat on Thursday Shiromani Akali Dal afternoon. chief Sukhbir Singh Thousands bid final Badal on Thursday con- adieu to their favourite demned the Haryana The protesting leader. government for trying farmers have to be Former party presi- to stop protesting farm- convinced about dent Rahul Gandhi was ers from reaching Del- the Minimum New Delhi: Prime Min- also present to pay his hi, terming the attempt ister Narendra Modi last respects to the party as “Punjab’s 26/11”. -

Report on Under Construction Renewable Energy Projects

भारत सरकार Government of India वि饍युत मंत्रालय Ministry of Power के न्द्री य वि 饍यु त प्रा धि क रण Central Electricity Authority निीकरणीय ऊ셍ाा पररयो셍ना प्रबोिन प्रभाग Renewable Energy Project Monitoring Division ननमााणािीन निीकरणीय ऊ셍ाा पररयो셍ना ररपो셍ा Report on under construction Renewable Energy Projects February-2020 1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Table of Contents Solar Power Projects ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Summary .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Physical Attributes ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Physical Progress ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Commercial Details............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Palaeochannels of the Thar Desert May Bring Prosperity for Its Inhabitants, Rajasthan, Nw India

PALAEOCHANNELS OF THE THAR DESERT MAY BRING PROSPERITY FOR ITS INHABITANTS, RAJASTHAN, NW INDIA. S.R. Jakhar Department of Geology, Faculty of Engineering, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India [email protected] KEY WORDS: River Linking, Former Courses, Forestation, Precipitation. ABSTRACT: The Thar Desert exists mainly in western part of the Rajasthan state of northwestern part of India. The state occupies an area about two third of the total area of the desert. Because of scarcity of rain fall in the desert, the frequency of occurrence of draughts is very high. The inhabitants of the desert are bound to migrate in search of water, food and fodder frequently. There are a number of palaeochannels exist in the Thar Desert of the western Rajasthan. The presence of these palaeochannels have been proved through study of remote sensing imageries and it is inferred that sometime in the past a very mighty Himalayan river and its tributaries were flowing through western Rajasthan and meeting Arabian Sea. India plans to transfer water from the water surplus regions of the north and north-east to the water scarce regions of western and southern India. The plan is called the National River Linking Project (NRLP). If the rivers of Himalaya are linked to Palaeochannel of the Thar Desert through canals, it will thrust up the economic condition of desert residents by increase of crop sowing area, tree plantation and fish production from aqua-culture. When water will flow through these pre-existing river courses in the desert, it will be available for irrigation, forestation, cultivation of grasses, aqua-culture, drinking and for industrial supply. -

Integrated Natural and Human Resources Appraisal of Jaisalmer District

CAZRI Publication No. 39 INTEGRATED NATURAL AND HUMAN RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF JAISALMER DISTRICT Edited by P.C. CHATTERJI & AMAL KAR mw:JH9 ICAR CENTRAL ARID ZONE RESEARCH INSTITUTE JODHPUR-342 003 1992 March 1992 CAZRI Publication No. 39 PUBLICA nON COMMITTEE Dr. S. Kathju Chairman Dr. P.C. Pande Member Dr. M.S. Yadav Member Mr. R.K. Abichandani Member Dr. M.S. Khan Member Mr. A. Kar .Member Mr. Gyanchand Member Dr. D.L. Vyas Sr. A.D. Mr. H.C. Pathak Sr. F. & Ac.O. Published by the Director Central Arid 20he Research In.Hitute, Jodhpur-342 003 * Printed by MIs Cheenu Enterprises, Navrang, B-35 Shastri Nagar, Jodhpur-342 003 , at Rajasthan Law Weekly Press, High Court Road, Jodhpur-342 001 Ph. 23023 CONTENTS Page Foreword- iv Preface v A,cknowledgements vi Contributors vii Technical support viii Chapter I Introduction Chapter II Climatic features 5 Chapter III Geological framework 12 Chapter- IV Geomorphology 14 ChapterY Soils and land use capability 26 Chapter VI Vegetation 35 Chapter VII Surface water 42 Chapter Vill Hydrogeological conditions 50 Chapter IX Minetal resources 57 Chapter X Present land use 58 Chapter XI Socio-economic conditions 62 Chapter XII Status of livestock 67 Chapter X III Wild life and rodent pests 73 Chapter XLV Major Land Resources Units: Characteristics and asse%ment 76 Chapter XV Recommendations 87 Appendix I List of villages in Pokaran and laisalmer Tehsils, laisalmer district, alongwith Major Land Resources Units (MLRU) 105 Appendix II List of villages facing scarcity of drinking water in laisalmer district 119 Appendix III New site~ for development of Khadins in Iaisalmer district ]20 Appendix IV Sites for construction of earthen check dams, anicuts and gully control structures in laisalmer district 121 Appendix V Natural resources of Sam Panchayat Samiti 122 CAZRI Publications , . -

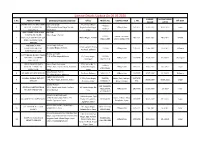

Tax Payers of Jaisalmer District Having Turnover Upto 1.5 Crore

Tax Payers of Jaisalmer District having Turnover upto 1.5 Crore Administrative S.No GSTN_ID TRADE NAME ADDRESS Control 1 CENTRE 08ACMPB6490R1ZT THAKUR JI AGENCIES MANAK CHOWK, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 2 STATE 08AKHPN5269P1ZA MAHAVEER STEELS PLOT NO. 10 , NEHRU NAGAR COLONY, JAISALMER ROAD, POKARAN, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345021 3 STATE 08BJBPS4946Q1ZC JAGDAMBA IRRIGATION NH 15, OPP. PURANA KILA ,FATEHGARH, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 4 STATE 08AALFM8509P1ZG MAHANAGAR DEVELOPERS A-60 R.P COLONY, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 5 STATE 08ADIPR1701L1ZF MURLI TOBOCOO COMPANY NEAR FORT ROAD, GHODO KA CHOWK, POKARAN, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345021 6 STATE 08ABAPK5657J1ZF B.L ENTERPRISES KUTCHHARI ROAD, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 7 STATE 08AHZPH1107M1ZY Shivam Keshav Enterprises SADAR BAZAR POKRAN, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345021 8 STATE 08ADDPC0146R1ZI BAJARANG TRADING COMPANY CHAURAHA, VILL- POKARAN, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345021 9 STATE 08AHEPR7426G1Z4 KAREENA DRY FRUIT GRAMIN BUS STAND, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 10 STATE 08AAHFH3774R1ZK HOTEL GULAAL INFRONT OF PUSHKARNA BERA, BERA ROAD, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 11 CENTRE 08AAACP5047P1ZZ PARAM CAPITAL RESEARCH PVT. LTD. A-60, R.P COLONY, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 12 STATE 08AJAPV5623P1ZL JAGDAMBA ENTERPRISES NEAR UPBHOKTA BHANDAR, SHIV ROAD, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 13 STATE 08CIUPS2805R1Z6 RIDHI SIDHI CONSTRUCTION NEAR POLICE LINE, KACHHI BASTI, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 14 STATE 08ACAPM7082L1Z8 KAPIL STONE G-102, RIICO IND AREA, JAISALMER, JAISALMER, 345001 15 STATE 08ANDPB7275N1ZM -

District Census Handbook, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 RAJASTHAN DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK JAISALMER DISTRICT c. S. GUPTA OF THB INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of CensU$ Operations. Rajasthan Printed by Maratla] Z. Gandhi. at Nayan Printing Press. Ahmedabad-I. FOREWORD The Census data has always been considered as indispensable for day to day administration. It is increasingly being considered now as the foundation stone of all regional planning. The publication of this series of District Census Handbooks wherein census - statistics is made available for smaller territorial units is, therefore, a significant occasion for it fills many existing gaps in statistics at the lower levels. Many interesting details have been revealed by the Census 1961 and I hope persons engaged in the administration of the State and public in general will appreciate the value and the effort that has gone into the production of such a standard book of reference. I congratulate the Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan, Shri C. S. Gupta I. A. S. and his colleagu,es who have done a good job with skill and perseverence. B. MEHTA JAIPUR, Chief Secretary 1st Alarch. 1966. to the Government of Rajasthan- PRft'ACE The District Census Handbooks, to which series the present volume belongs, are the gifts of the Census of India and were first introduced in 1951. The 1961 series of District Census Handbooks are more elaborate than their counter-part in 1951 and present all important census data alongwith such other basic information as is very z:elevant for an understanding of the district. A wide variety of information which the Census 1961 collected has already been released in several parts as mentioned elsewhere in this book. -

License Details Update on 06.05.2020 LICENSE LICENSE VALID S.No

License Details Update On 06.05.2020 LICENSE LICENSE VALID S.No. AGENCY NAME Director/Propriter/Partner Office Mobile No. LICENCE AREA L. NO. Off-Distt. ISSUED UP TO DESERT HAWK EX-SERVICEMEN Raghuveer Singh A-6, Vinobha Bhave 2350332, 1 WELFARE CO-OPRETIVE B-78,Vinobha Bhave Nagar,Vaishali Nagar,Vaishali Nagar, All Rajasthan 1/STATE 17.03.2007 16.03.2022 Jaipur 2359257 SOCIETY LTD. Nagar,Jaipur Jaipur MARU PRAHRI SEVA NIVRAT Zor Singh SURKSHA BAL SAINIK Nehru Nagar , Barmer 222052, Barmer, Jaisalmer, 2 INVESTIGATION WELFARE CO- Nehru Nagar , Barmer 10/STATE 19.06.2007 18.6.2022 Barmer 9414755889 Jalore, Jodhpur, Pali PORETIVE SOCIETY LTD. BARMER BHILWARA ZILA EX- Umrao Singh Rathore Ashok Leyland Chraha, 3 SERVICEMEN WELFARE 36-1,Babu Nagar, Bhilwara. 2244202 All Rajasthan 12/STATE 25.06.2007 24.6.2022 Bhilwara Pur Road, Bhilwara SAHKARI SAMITI LTD. Gheesu Lal Khatik CHITTORGARH EX-SERVICEMEN 10-E-56,Tilak Nagar,Bhilwara 62, Pratap Nagar, 2244203, 4 WELFARE CO-OPRETIVE All Rajasthan 13/STATE 25.06.2007 24.6.2012 Chittorgarh Chittorgarh 9829517418 SOCIETY LTD. JAIPUR EX-SERVICEMEN Sumer Singh Shekhawat 17/1, Sector No. 4, 2205833, 5 WELFARE CO-PORETIVE 27-A/1, Kanti Chandra Road, Bani Park, Vidhyadhar Nagar, All Rajasthan 14/STATE 30.06.2007 29.6.2022 Jaipur 9414041603 SOCIETY LTD. Jaipur Jaipur Satya Narayan Pareek 6 RELIANCE SECURITY SERVICES Pur Road, Bhilwara 9414113217 All Rajasthan 21/STATE 30.07.2007 29.7.2022 Bhilwara 66, Subhash Nagar, Bhilwara Jagdish Prasad Sharma KUMBHJI DARBAR SECURITY E-52 A, Prem Nagar, 2342556, Jaipur, Tonk, Jodhpur, 22/STATE/ 7 E-73, Prem Nagar, Jhotwara, Jaipur. -

December 2012

Small Mammal Mail Newsletter celebrating the most useful yet most neglected Mammals for CCINSA & RISCINSA -- Chiroptera, Rodentia, Insectivora, & Scandentia Conservation and Information Networks of South Asia Volume 4 Number 2 ISSN 2230-7087 DECEMBER 2012 Contents Members Editorial, P. 2 CCINSA Members since Feb 2012 Ms. Khushbu Panwar, Research First Record of habitat sharing of Eonycteris Scholar, Dept. of Zoology, M.L.S. Univ., spelaea and Rousettus leschenaultii in Nepal Udaipur, Rajasthan Dr. Amir Hossan Shaikat, Lecturer, and Highest Elevation of Occurrence of E. <[email protected]> spelaea in the World, Sanjan Thapa, Dibya Dept. of Physiology, Biochem. & Raj Dahal and Santoshi Pokhrel, Pp. 3-7 Pharmacology, Chittagong Vet. & Animal Sci. Univ., Chittagong, Bangladesh Mr. Rohit Ashit Chakravarty, Student, St. Xavier College, Mumbai, Maharashtra Additional site records of Indian Pangolin <[email protected]> (Manis crassicaudata Gray 1827) <[email protected]> (Pholidota; Manidae) in Guntur, K. Mr. Deependar Singh Shekhawat, Mahabubnagar and Medak districts of Research Scholar, Dept. of Zoology, M.L.S. Mr. Devendra Kumar, Research Scholar, Andhra Pradesh, India, K. Krishna Prasad, Univ., Udaipur, Rajasthan Dept. of Zoology, M.L.S. Univ., Udaipur, and C. Srinivasulu, Pp. 8-9. <[email protected]> Rajasthan <[email protected]> Recent Observations of Black Giant Squirrel Mr. Vijay Kumar Koli, Research Scholar, Ratufa bicolor (Sparrman, 1778) in the Dr. Samir Kumar Sinha, WTI Field Dept. of Zoology, M.L.S. Univ., Udaipur, Vicinity of Makalu-Barun National Park, Station, Valmiki Tiger Reserve, Patna, Rajasthan Nepal, Yadav Ghimirey, Binod Ghimire, Bal Bihar <[email protected]> Mukunda Pokhrel and Raju Acharya, Pp. <[email protected]> 10-11. -

Rajasthan Renewable Energy Corporation Limited (Government of Rajasthan Undertaking) CIN: U40101RJ1995SGC009847

Rajasthan Renewable Energy Corporation Limited (Government of Rajasthan Undertaking) CIN: U40101RJ1995SGC009847 Request for Selection (RfS) For Selection of Developers for setting upof decentralized Solar PV Plants each of 0.5 MW to 2 MW (AC) aggregating to total 113.5MW capacity At Discom‟s 33/11kV Substations in Rajasthan Tender No. RREC/DSPP/2019-20/06 Dt. 09/09/2019 TENDER SEARCH CODE: RRECL-2019-TN000001 E-166, Yudhisthir Marg, C-Scheme, Jaipur-302001 Tel: 0141 - 2225859, 2223966 Fax: 0141 - 2226028 E mail: [email protected] TM:RREC/DSPP/019-20/06 Page 1 DISCLAIMER 1. Though adequate care has been taken while preparing the RfS document, the bidder(s) shall satisfy themselves that the document is complete in all respect. Intimation regarding any discrepancy shall be given to the office of RRECL immediately. If no intimation is received from any bidder within 7(seven) days from the date of issuance of RfS documents, it shall be considered that the document is complete in all respect and has been received / acknowledged by the bidder(s). 2. Rajasthan Renewable* Energy Corporation Limited (RRECL) reserves the right to modify, amend or supplement this document. 3. While this RfS document has been prepared in good faith, neither RRECL nor their employees or advisors make any representation or warranty, express or implied, or accept any responsibility or liability, whatsoever, in respect of any statements or omissions herein, or the accuracy, completeness or reliability of information, and shall incur no liability under any law, statute, rules or regulations as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of this document, even if any loss or damage is caused by any act or omission on their part. -

Jodhpur Vidyut Vitran Nigam Limited New Power House, Jodhpur-342003 Telephone No

JdVVNL/SE/TW/Tender Specs CLRC/TN TW-540 JODHPUR VIDYUT VITRAN NIGAM LIMITED BIDDING DOCUMENT “CONSTRUCTION OF 06 NOS. 33/11 KV, 1X 3.15 MVA SUB-STATION (PADAMSAGAR, GOVINADPURA, SATYAYA FANTA, NACHANA-II, MEKUBA AND KHETOLAI) AND THEIR ASSOCIATED 37.10 KM 33 KV LINE AND 52.00 KM 11 KV INTERCONNECTION WORK UNDER JAISALMER CIRCLE ON LABOUR RATE BASIS”, IN THE JURISDICTION OF JODHPUR DISCOM. PACKAGE NO. JDVVNL / SE/ TW/TNTW-540 SUPERINTENDING ENGINEER (TW) JODHPUR VIDYUT VITRAN NIGAM LIMITED NEW POWER HOUSE, JODHPUR-342003 TELEPHONE NO. 0291-2742336 FAX NO.0291-2745259 [email protected] Bid Cost: Rs. 2500+ Rs450 (GST) = Rs. 2950/- for each Page 1 of 84 JdVVNL/SE/TW/Tender Specs CLRC/TN TW-540 JODHPUR VIDYUT VITRAN NIGAM LTD. Corporate Identity Number (CIN) –U40109RJ2000SGC016483 Regd. Office: New Power House, Jodhpur- 342003 OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDING ENGINEER (TW) Phone No: 0291-2742343, Fax No: 0291-2741772 E-mail: [email protected], Web site: www. https://energy.rajasthan.gov.in/jdvvnl No: JdVVNL/ JU/SE (TW)/F.TN TW- 540/ D. Date E-PROCUREMENT SHORT TERM TENDER NOTICE Techno-commercial and Price short term e-Bids are invited from eligible bidders for following work on Labour Rate Basis:- Name of work: “Construction of 06 Nos. 33/11 KV, 1x 3.15 MVA sub-station (Padamsagar, Govinadpura, Satyaya Fanta, Nachana-II, Mekuba and Khetolai) and their associated 37.10 KM 33 KV Line and 52.00 KM 11 KV Interconnection work under Jaisalmer Circle on Labour Rate basis”. Total Tender Cost of Bid Security Bid Last Date and Technical Bid Sr. -

International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanities

International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanities ISSN 2277 – 9809 (online) ISSN 2348 - 9359 (Print) An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust www.IRJMSH.com www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions IRJMSH Vol 5 Issue 10 [Year 2014] ISSN 2277 – 9809 (0nline) 2348–9359 (Print) Dalit Access to Land in Rajasthan: Land Reform as Redistributive Justice since Independence Lakshmi Narayan Singh Reena Gupta Research Scholar (PhD) Research Scholar (PhD) Department of History and Culture Department of Educational Studies Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi ―We have no land because others have usurped it ...‖ -Dr. Ambedkar Abstract In the traditional Hindu hierarchical society Dalits were called Shudras or Harijans or Panchmas and were socially, economically and politically a suppressed people. Placed at the bottom of the caste hierarchy they survived by performing functions like scavenging, leatherwork, etc. During colonial period they constituted the bulk of the agricultural labour force and worked as farm servants and casual labourers. Very few (less than 10%) Dalit families possessed agricultural land. They had no right to own land nor were they considered to be peasants or tillers of the soil. The existing social customs did not grant them the status of occupancy tenant, though they might have cultivated lands as tenants and sharecroppers. In the case of untouchables, therefore, there was a clear correspondence/correlation between social and economic status. Land is the basis of all economic activity. It is the most important asset in an agrarian economy like India where majority of the population in rural areas are dependent on agriculture, labour and animal husbandry. -

1.48 Ha Village –Phalsoond, Tehsil –Bhaniyana, District - Jaisalmer (Raj.) Pre -Feasibility Report

Gypsum Permit, Ref No-2017160585 Production Capacity -1925 TPA, Area- 1.48 ha Village –Phalsoond, Tehsil –Bhaniyana, District - Jaisalmer (Raj.) Pre -Feasibility Report INDEX 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... 06 2 INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT/ BACKGROUND INFORMATION ................ 10 2.1 IDENTIFICATION OF PROJECT AND PROJECT PROPONENT ......................................... 10 2.2 NEED FOR THE PROJECT & ITS IMPORTANCE TO THE COUNTRY/ REGION .......... 11 2.3 DEMAND – SUPPLY GAP ....................................................................................................... 12 2.4 IMPORTS VS. INDIGENOUS PRODUCTION ........................................................................ 12 2.5 EXPORT POSSIBILITY ............................................................................................................ 12 2.6 DOMESTIC/EXPORT MARKETS ............................................................................................ 12 2.7 EMPLOYMENT GENERATION (DIRECT AND INDIRECT) DUE TO THE PROJECT ..... 12 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................. 13 3.1 TYPE OF PROJECT INCLUDING INTERLINKED AND INDEPENDENT PROJECTS, IF ANY ............................................................................................................................................ 13 3.2 LOCATION (MAP SHOWING GENERAL LOCATION, SPECIFIC LOCATION, AND PROJECT BOUNDARY & PROJECT