Invitation to Holy Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of the Ramakrishna Mission and Human

TOWARDS SERVING THE MANKIND: THE ROLE OF THE RAMAKRISHNA MISSION AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA Karabi Mitra Bijoy Krishna Girls’ College Howrah, West Bengal, India sanjay_karabi @yahoo.com / [email protected] Abstract In Indian tradition religious development of a person is complete when he experiences the world within himself. The realization of the existence of the omnipresent Brahman --- the Great Spirit is the goal of the spiritual venture. Gradually traditional Hinduism developed negative elements born out of age-old superstitious practices. During the nineteenth century changes occurred in the socio-cultural sphere of colonial India. Challenges from Christianity and Brahmoism led the orthodox Hindus becoming defensive of their practices. Towards the end of the century the nationalist forces identified with traditional Hinduism. Sri Ramakrishna, a Bengali temple-priest propagated a new interpretation of the Hindu scriptures. Without formal education he could interpret the essence of the scriptures with an unprecedented simplicity. With a deep insight into the rapidly changing social scenario he realized the necessity of a humanist religious practice. He preached the message to serve the people as the representative of God. In an age of religious debates he practiced all the religions and attained at the same Truth. Swami Vivekananda, his closest disciple carried the message to the Western world. In the Conference of World religions held at Chicago (1893) he won the heart of the audience by a simple speech which reflected his deep belief in the humanist message of the Upanishads. Later on he was successful to establish the Ramakrishna Mission at Belur, West Bengal. -

Download the Book from RBSI Archive

CO Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/citiesofindiaOOforruoft TWO INDISPENSABLE REFERENCE BOOKS ON INDIA Constable's Hand Atlas of India A Series of Sixty Maps and Plans prepared from Ordnance and other Surveys under the Direction of J. G. BARTHOLOMEW, F.R.G.S., F.R.S.E., etc. Crown 8vo. Strongly bound in Half Morocco, 14J. This Atlas will be found of great use, not only to tourists and travellers, but also to readers of Indian History, as it contains twenty-two plans of the principal towns of our Indian Empire, based on the most recent surveys and officially revised in India. The Topographical Section Maps are an accurate reduction of the Survey of India, and contain all the places described in Sir W. W. Hunter's "Gazetteer of India," according to his spelling. The Military Railway, Telegraph, and Mission Station Maps are designed to meet the requirements of the Military and Civil Service, also missionaries and business men who at present have no means of ob- taining the information they require in a handy form. The Index contains upwards of ten thousand names, and will be found more complete than any yet attempted on a similar scale. Further to increase the utility of the work as a reference volume, an abstract of the i8qi Census has been added. UNIFORM WITH THE ABOVE Constable's Hand Gazetteer of India Compiled under the Direction of F.R.G.S., and Edited J. G. BARTHOLOMEW, with Additions by Jas. Burgess, CLE., LL.D., etc. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Alcove Flora Fountain

https://www.propertywala.com/alcove-flora-fountain-kolkata Alcove Flora Fountain - Topsia, Kolkata An embodiment of refreshing water bodies and sprawling landscaped greens Alcove Flora Fountain is presented by Alcove Realty at Tangra, Topsia, Kolkata offers residential project that hosts 2, 3 and 4 BHK apartment with good features Project ID: J289645611 Builder: Alcove Realty Location: Flora Fountain, Tangra, Topsia, Kolkata - 700046 (West Bengal) Completion Date: Dec, 2021 Status: Started Description Alcove Flora Fountain by Alcove Realty located at Tangra, Topsia, Kolkata redefines the standard of living with architectural excellence. Project spread over 899 sq. ft.-1882 sq. ft. comprising of 2,3 and 4 bhk apartments. The project is equipped with key amenities including fire safety systems, swimming pool, kids pool etc. & well connected with other parts of city and has all the basic utilities. RERA ID : HIRA/P/KOL/2018/000050 Amenities: swimming pool kids pool locker facilities an AC lounge outdoor yoga deck Alcove Reaqlty, One of the most renowned, trusted and exemplary name in the sphere of real estate - Alcove Realty, spearheaded by the legendary Mr. Amar Nath Shroff, came into existence to set an indelible benchmark with its landmark projects. With forty glorious years of experience, this ‘3 Generation’ company is beheld with distinction and respect among all the renowned builders in Kolkata, at the helm of the industry. Features Security Features Exterior Features Fire Alarm Reserved Parking Recreation Land Features Swimming Pool -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Thevedanta Kesari February 2020

1 TheVedanta Kesari February 2020 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story Sri Ramakrishna : A Divine Incarnation page 11 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly 1 `15 February of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2020 2 Mylapore Rangoli competition To preserve and promote cultural heritage, the Mylapore Festival conducts the Kolam contest every year on the streets adjoining Kapaleswarar Temple near Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai. Regd. Off. & Fact. : Plot No.88 & 89, Phase - II, Sipcot Industrial Complex, Ranipet - 632 403, Tamil Nadu. Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Phone : 04172 - 244820, 651507, PRIVATE LIMITED Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Tele Fax : 04172 - 244820 (Manufacturers of Active Pharmaceutical Printed by B. Rajkumar, Chennai - 600 014 on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trust, Chennai - 600 004 and Ingredients and Intermediates) E-mail : [email protected] Web Site : www.svisslabss.net Printed at M/s. Rasi Graphics Pvt. Limited, No.40, Peters Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600014. Website: www.chennaimath.org E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 6374213070 3 THE VEDANTA KESARI A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of The Ramakrishna Order Vol. 107, No. 2 ISSN 0042-2983 107th YEAR OF PUBLICATION CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2020 ory St er ov C 11 Sri Ramakrishna: A Divine Incarnation Swami Tapasyananda 46 20 Women Saints of FEATURES Vivekananda Varkari Tradition Rock Memorial Atmarpanastuti Arpana Ghosh 8 9 Yugavani 10 Editorial Sri Ramakrishna and the A Curious Boy 18 Reminiscences Pilgrimage Mindset 27 Vivekananda Way Gitanjali Murari Swami Chidekananda 36 Special Report 51 Pariprasna Po 53 The Order on the March ck et T a le 41 25 s Sri Ramakrishna Vijayam – Poorva: Magic, Miracles Touching 100 Years and the Mystical Twelve Lakshmi Devnath t or ep R l ia c e 34 31 p S Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Printed by B. -

IN MEMORIAM REVERED SWAMI SWAHANANDAJI I Met Revered

IN MEMORIAM REVERED SWAMI SWAHANANDAJI SWAMI TATHAGATANANDA I met Revered Swami Swahanandaji at Saradapith. In 1956, he came to Belur Math to be ordained in Sannyas. As he was ex-monastic member of Saradapith, he came to visit Sarapith Ashrama. His father’s name was Nirmal Chandra Goswami and his mother was Pramila Bala. His father was initiated by Holy Mother. At one point, his father requested Holy Mother to become a monk. Holy Mother replied, “No, my child. Two members of your family will become monks.” This prophecy was fulfilled. His father passed away two months before the birth of his third child. On June 29, 1921, the child was born in a religious family in a small village in Assam, which is today in Bangladesh. His name was Bipadbhanjan. While he was reading in school, he used to frequent the Ramakrishna Ashram and rendered some service. When he was fourteen years old, he wrote a letter to Rev. Swami Akhandananda. During the Centenary Celebration of Shri Ramakrishna in 1936, he came to Belur Math as a volunteer and had the unique opportunity of getting initiation from Rev. Swami Vijnanananda. He also had another unique opportunity in seeing Revered Swami Abhedananda. He also met Revered Swamis Parameshananda and Saradeshanada and he remained close to both the Swamis throughout his life. He was a good student and secured a letter mark in Sanskrit (80%) in his matriculation examination. He passed his B. A. examination from Murari Chand College, Sylhet. He came to Calcutta to study for his M. A. He joined the Institute of Culture, which was located at Wellington Square. -

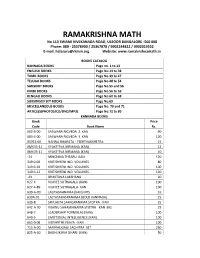

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

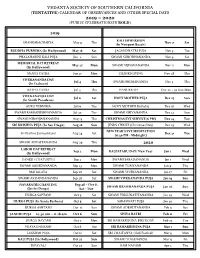

2021 2020 2021

VEDANTA SOCIETY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA CALENDAR OF OBSERVANCES AND OTHER SPECIAL DAYS 2020 – 2021 (PUBLIC CELEBRATIONS IN BOLD) KALI IMMERSION Nov 17 Tue 2020 (In Newport Beach) SHANKARACHARYA Apr 28 Tue JAGADDHATRI PUJA Nov 23 Mon BUDDHA PURNIMA (In Hollywood) May 7 Thu THANKSGIVING Nov 26 Thu PHALAHARINI KALI PUJA May 22 Fri SWAMI SUBODHANANDA Nov 26 Thu MEMORIAL DAY RETREAT May 25 Mon SWAMI VIJNANANANDA Nov 29 Sun (In Hollywood) SNANA YATRA Jun 5 Fri HANUKKAH Dec 10 – 18 Thu - Fri RATHA YATRA Jun 23 Tue SWAMI PREMANANDA Dec 23 Wed VIVEKANANDA DAY CHRISTMAS EVE SERVICE Jul 4 Sat Dec 24 Thu (In Trabuco) (6 PM) GURU PURNIMA Jul 5 Sun JESUS CHRIST (Christmas Day) Dec 25 Fri VIVEKANANDA DAY NEW YEAR'S EVE MEDITATION Jul 11 Sat Dec 31 Thu (In South Pasadena) (11:30 PM - Midnight) SWAMI RAMAKRISHNANANDA Jul 18 Sat 2021 SWAMI NIRANJANANANDA Aug 3 Mon KALPATARU DAY Jan 1 Fri SRI KRISHNA PUJA Aug 9 Sun HOLY MOTHER Celebration Jan 3 Sun (In San Diego) Sri Krishna Janmashtami Aug 11 Tue HOLY MOTHER BIRTHDAY Jan 5 Tue SWAMI ADVAITANANDA Aug 18 Tue SWAMI SHIVANANDA Jan 9 Sat GANESH CHATURTHI Aug 22 Sat SWAMI SARADANANDA Jan 19 Tue LABOR DAY RETREAT Sep 7 Mon SWAMI TURIYANANDA Jan 27 Wed (In Hollywood) SWAMI ABHEDANANDA Sep 11 Fri SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Feb 4 Thu MAHALAYA Sep 17 Thu SWAMI VIVEKANANDA PUJA Feb 7 Sun SWAMI AKHANDANANDA Sep 17 Thu SWAMI BRAHMANANDA Feb 13 Sat NAVARATRI CHANTING Oct 17 – 26 SWAMI BRAHMANANDA PUJA Feb 14 Sun (Jai Sri Durga) Sat - Mon DURGA SAPTAMI Oct 23 Fri SWAMI TRIGUNATITANANDA Jan 15 Mon DURGA ASHTAMI Oct 24 Sat SARASWATI PUJA Feb 16 Tue SANDHI PUJA (6.35 am – 7.23 am) Oct 24 Sat SWAMI ADBHUTANANDA Feb 27 Sat DURGA PUJA (In Santa Barbara) Oct 24 Sat SHIVA RATRI Mar 11 Thu DURGA NAVAMI Oct 25 Sun SRI RAMAKRISHNA Celebration Mar 14 Sun VIJAYA DASHAMI Oct 26 Mon SRI RAMAKRISHNA BIRTHDAY Mar 15 Mon LAKSHMI PUJA Oct 30 Fri SRI CHAITANYA (Holi Festival) Mar 28 Sun KALI PUJA (In Hollywood) Nov 14 Sat SWAMI YOGANANDA Apr 1 Thu . -

Calcutta in 3 Giorni

Calcutta in 3 giorni Kolkata, fino al gennaio 2001 chiamata Calcutta, è la capitale dello stato del Bengala Occidentale dell'India. Si trova sulle rive del fiume Hooghly ed è il principale centro commerciale, culturale ed educativo dell'India orientale. Può sembrare troppo caotico per poter vedere Calcutta in 3 giorni ma grazie alla nostra guida sarete in grado di vederlo perfettamente in una breve fuga. Cosa vedere a Calcutta in 3 giorni? È la terza area metropolitana più produttiva dell'India, dopo Mumbai e Delhi. Si chiama anche la Città della Gioia. Consigli per visitare Calcutta Il trasporto tradizionale di Calcutta è il risciò, ma attualmente è stato parzialmente vietato dal governo. Oggi vengono utilizzati più taxi e minibus per spostarsi in città. Ha un aeroporto internazionale. Gastronomia a Calcutta La maggior parte del cibo indiano ha sapori e aromi forti. Nei ristoranti troverete cucina del nord e del sud dell'India, cucina tailandese, cinese, tibetana e persino anglo-indiana come l'India è stata per lungo tempo una colonia britannica. Un alimento tipico è il macher jhol, è pesce con curry e riso o pesce marinato con senape e cotto a vapore. Alcuni dei suoi dolci tipici sono: I Rosomalai sono palline di formaggio bagnate nel latte dolce e cremoso. La pantua è un'altra varietà delle stesse palline di formaggio. Rasagolla è una varietà diversa che si mangia con il miele. Altre destinazioni in India Itinerario Calcutta Guida: Giorno 1 Il primo giorno può essere dedicato a vedere il Tempio Dakshineswar Kali (Tempio Dakshineswar Kali), il Belur Math (Belur Math, Kolkata), il Ponte Howrah (Ponte Howrah, Kolkata), la Casa Tagore (Jorasanko Thakur Bari, Kolkata), il Palazzo di Marmol (Palazzo di Marmo, Kolkata), e la Moschea di Hakhoda (Moschea di Hakhoda, Kolkata), se avete tempo potete visitare l'Eco Tourism Park (Eco Tourism Park, Kolkata), che è un po 'ritirata ma vale la pena di vedere. -

2020 2019 2020

VEDANTA SOCIETY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA (TENTATIVE) CALENDAR OF OBSERVANCES AND OTHER SPECIAL DAYS 2019 – 2020 (PUBLIC CELEBRATIONS IN BOLD) 2019 KALI IMMERSION SHANKARACHARYA May 9 Thu Nov 2 Sat (In Newport Beach) BUDDHA PURNIMA (In Hollywood) May 18 Sat JAGADDHATRI PUJA Nov 5 Tue PHALAHARINI KALI PUJA Jun 2 Sun SWAMI SUBODHANANDA Nov 9 Sat MEMORIAL DAY RETREAT May 27 Mon SWAMI VIJNANANANDA Nov 11 Mon (In Hollywood) SNANA YATRA Jun 17 Mon THANKSGIVING Nov 28 Thu VIVEKANANDA DAY Jul 4 Thu SWAMI PREMANANDA Dec 5 Thu (In Trabuco) RATHA YATRA Jul 4 Thu HANUKKAH Dec 22 – 30 Sun-Mon VIVEKANANDA DAY Jul 6 Sat HOLY MOTHER PUJA Dec 15 Sun (In South Pasadena) GURU PURNIMA Jul 16 Tue HOLY MOTHER Birthday Dec 18 Wed SWAMI RAMAKRISHNANANDA Jul 30 Tue SWAMI SHIVANANDA Dec 22 Sun SWAMI NIRANJANANANDA Aug 15 Thu CHRISTMAS EVE SERVICE(6 PM) Dec 24 Tue SRI KRISHNA PUJA (In San Diego) Aug 18 Sun JESUS CHRIST (Christmas Day) Dec 25 Wed NEW YEAR'S EVE MEDITATION Sri Krishna Janmashtami Aug 24 Sat Dec 31 Tue (11:30 PM - Midnight) SWAMI ADVAITANANDA Aug 29 Thu 2020 LABOR DAY RETREAT Sep 2 Mon KALPATARU DAY/ New Year Jan 1 Wed (In Hollywood) GANESH CHATURTHI Sep 2 Mon SWAMI SARADANANDA Jan 1 Wed SWAMI ABHEDANANDA Sep 23 Mon SWAMI TURIYANANDA Jan 9 Thu MAHALAYA Sep 28 Sat SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Jan 17 Fri SWAMI AKHANDANANDA Sep 28 Sat SWAMI VIVEKANANDA PUJA Jan 19 Sun NAVARATRI CHANTING Sep 28 – Oct 8, SWAMI BRAHMANANDA PUJA Jan 26 Sun (Jai Sri Durga) Sat - Tue DURGA SAPTAMI Oct 5 Sat SWAMI TRIGUNATITANANDA Jan 29 Wed DURGA PUJA (In Santa Barbara) Oct 5 Sat SARASWATI PUJA Jan 30 Thu DURGA ASHTAMI Oct 6 Sun SWAMI ADBHUTANANDA Feb 9 Sun SANDHI PUJA 10.30 am – 11.18 am Oct 6 Sun SHIVA RATRI Feb 21 Fri DURGA NAVAMI Oct 7 Mon SRI RAMAKRISHNA BIRTHDAY Feb 25 Tue VIJAYA DASHAMI Oct 8 Tue SRI RAMAKRISHNA PUJA Mar 1 Sun LAKSHMI PUJA Oct 12 Sat SRI CHAITANYA (Holi Festival) Mar 9 Mon KALI PUJA (In Hollywood) Oct 27 Sun SWAMI YOGANANDA Mar 13 Fri DIPAVALI Oct 27 Sun RAM NAVAMI Apr 2 Thu . -

Centers and Locations of Ramakrishna Math & Ramakrishna Mission.Pdf

CENTRES IN INDIA Andaman Port Blair Ramakrishna Mission Port Blair Andaman, Andaman 744104 India Phone : 03192-232432 & 242278 Telefax : 03192-234538 Email : [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.portblairrkm.org (Click here for the activities of the centre) Andhra Pradesh Kadapa Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission 5/476, Trunk Road, Kadapa 516005, Putlampalli, Near RIMS Hospital, Kadapa 516002 Kadapa, Dt. YSR, Andhra Pradesh India Phone : 08562-241633, (08562) 20-0120 & (08562) 29-0633 Email : [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.rkmkadapa.org (Click here for the activities of the centre) Rajahmundry Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Nagar Rajahmundry, Dt. East Godavari, Andhra Pradesh 533105 India Phone : 0883-2473112 Email : [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.rkmathrjy.org (Click here for the activities of the centre) Institution(s): Town Centre Phone: 2478 127 Tirupati Ramakrishna Mission Ashrama Ramakrishna Marg Vinayaka Nagar, Tirupati Dist. Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh 517507 India Phone : (0877) 2234790 Email : [email protected] Vijayawada Ramakrishna Mission Ramakrishna Mission Road, Sitanagaram, Tadepalli Mandal, Dt. Krishna, Andhra Pradesh 522501 India Phone : (08645) 272248 & 272656, (0866) 2570799 Email : [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.rkmissionvijayawada.org (Click here for the activities of the centre) City/Town/Sub Centre(s) : Ramakrishna Mission Gandhinagar Vijaywada, Andhra Pradesh 520003 Phone : 0866-2570799 Visakhapatnam Ramakrishna Mission Ashrama Ramakrishna Beach Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530003 India Phone : 0891-2562561 & 2533186 Email : [email protected] Website: www.rkmissionvizag.org (Click here for the activities of the centre) Institution(s): School Phone: 2706 855 Arunachal Pradesh Along Ramakrishna Mission P.O.