World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiscal Policy Impact on Tobacco Consumption in High Smoking Prevalence Transition Economies - the Case of Albania

Fiscal policy impact on tobacco consumption in high smoking prevalence transition economies - the case of Albania Aida Gjika, Faculty of Economics, University of Tirana and Development Solutions Associates, Klodjan Rama, Faculty of Agriculture, Agricultural University of Tirana and Development Solutions Associates Edvin Zhllima, Faculty of Economics and Agribusiness, Agricultural University of Tirana, Development Solutions Associates and CERGE EI Drini Imami, Faculty of Economics and Agribusiness, Agricultural University of Tirana, Development Solutions Associates and CERGE EI Abstract This paper analysis the determinant factors of tobacco consumption in of Albania, which is one of the countries with highest smoking prevalence in Europe. To empirically estimate the elasticity of cigarettes demand in Albania, this paper uses the Living Standard Measurement Survey (LSMS) applying the Deaton’s (1988) demand model. Our paper estimates an Almost Ideal Demand System (AIDS), which allows disentangling quality choice from exogenous price variations through the use of unit values from cigarette consumption. Following a three-stage procedure, the estimated results suggest that the price elasticity is around -0.57. The price elasticity appears to be within the range of estimated elasticities in developing countries and in line with the estimates elasticities from the model using aggregate data. In terms of the control variables, it seems that the total expenditure, household size, male to female ratio and adult ratio are important determinants of tobacco demand in Albania. Thus, since an increase in price, which have been mainly driven by the increases of taxes, have demonstrated to have had a significant impact on tobacco consumption, the government should further engage in gradual increase of taxation. -

Beyond Transition

40957 The Newsletter About Reforming Economies Public Disclosure Authorized Beyond Transition January March 2007 • Volume 18, No. 1 http://www.worldbank.org/transitionnewsletter www.cefir.ru European Accession and CapacityBuilding Priorities John S. Wilson, Xubei Luo, and Harry G. Broadman 6 Internal Labor Mobility and Regional Labor Market Disparities Pierella Paci, Erwin Tiongson, Mateusz Walewski, Jacek Liwinski, Maria Stoilkova 8 Latvian Labor Market before and after EU Accession Public Disclosure Authorized Mihails Hazans 10 The Impact of EU Accession on Poland's Economy Ewa Balcerowicz 11 Bulgaria's Integration into the PanEuropean Economy Bartlomiej Kaminski and Francis Ng 13 Forming Preferences on European Integration: the Case of Slovakia Tim Haughton and Darina Malova 15 Insert: Whither Europe? 16 Credit Expansion in Emerging Europe 17 Public Disclosure Authorized New Findings The Economic Cost of Smoking in Russia Michael Lokshin and Zurab Sajaia 18 Insert: Smoking in Albania 19 Deregulating Business in Russia Ekaterina Zhuravskaya, Evgeny Yakovlev 20 Land and Real Estate Transactions for Businesses in Russia Photo: ECA, the World Bank Gregory Kisunko and Jacqueline Coolidge 21 Insert: Land Issues: Barriers for Small Businesses 22 Theme of the Issue: EU Enlargement Foreign Bank Profitability in Central and Eastern Europe Public Disclosure Authorized Olena Havrylchyk and Emilia Jurzyk 23 EMU Enlargement: Why Flexibility Matters Banking in Ukraine: Changes Looming? Philipp Maier and Maarten Hendrikx 3 Natalya Dushkevych and Valentin Zelenyuk 24 Gains from RiskSharing in the EU World Bank Agenda 25 Yuliya Demyanyk and Vadym Volosovych 4 New Books and Working Papers 27 Postponing EuroArea Expectations? Tanel Ross 5 Conference Diary 30 2 · From the Editor: Dear Reader, As with the previous issue of BT, which discussed the economic prospects of the Central Asian states, this issue also has a geographic focus. -

Albania Environmental Performance Reviews

Albania Environmental Performance Reviews Third Review ECE/CEP/183 UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE REVIEWS ALBANIA Third Review UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2018 Environmental Performance Reviews Series No. 47 NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. In particular, the boundaries shown on the maps do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. The United Nations issued the second Environmental Performance Review of Albania (Environmental Performance Reviews Series No. 36) in 2012. This volume is issued in English only. Information cut-off date: 16 November 2017. ECE Information Unit Tel.: +41 (0)22 917 44 44 Palais des Nations Fax: +41 (0)22 917 05 05 CH-1211 Geneva 10 Email: [email protected] Switzerland Website: http://www.unece.org ECE/CEP/183 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No.: E.18.II.E.20 ISBN: 978-92-1-117167-9 eISBN: 978-92-1-045180-2 ISSN 1020–4563 iii Foreword The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (ECE) Environmental Performance Review (EPR) Programme provides assistance to member States by regularly assessing their environmental performance. Countries then take steps to improve their environmental management, integrate environmental considerations into economic sectors, increase the availability of information to the public and promote information exchange with other countries on policies and experiences. -

Anti Tobacco

REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA Council of Ministers DECISION No._513____ ,dated __19.7.2006_____ ON PROPOSAL OF BILL “ON HEALTH PROTECTION FROM TOBACCO PRODUCTS” On the strength of articles 81, item , and 100 of the Constitution, by the proposal of Minister of Health, Council of Ministers Decided: Proposal of the bill “On health protection from tobacco products” for examination and approval in the Assembly of Republic of Albania, according to the text and report that are attached to this decision. This decision enters in force immediately. PRIME MINISTER (signature) SALI BERISHA MINISTER OF HELTH MAKSIM CIKULI (signature) REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA ASSEMBLY BILL No_9636__, dated _6.11.2006________ ON HEALTH PROTECTION FROM TOBACCO PRODUCTS BASED ON THE ARTICLES 78 AND 1, OF THE Constitution, at the proposal of the Council of Ministers, the Parliament of Republic of Albania DECIDED CHAPTER 1 ARTICLE 1 GENERAL PROVISION Article 1 Purpose Purpose of this law is protection of public health from the use of tobacco products and involuntary exposure to their smoke. Article 2 Object Object of this law are: a) defining of measures for restricting the use of tobacco products and protection of the public from dangers by involuntary exposure to their smoke. b) defining of measures that create premises for making the public aware about the harm of tobacco and guaranteeing of an effective and continuous information of users of tobacco products for this harm. c) defining of measures to prevent the start, to encourage and support interruption of use and reduce the consumption of tobacco products. Article 3 Definitions For purposes of this law, the following terms mean: 1. -

Albania Health Care Systems in Transition I

European Observatory on Health Care Systems Albania Health Care Systems in Transition I IONAL B AT AN RN K E F T O N R I WORLD BANK PLVS VLTR R E T C N O E N M S P T R O U L C E T EV ION AND D The European Observatory on Health Care Systems is a partnership between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, the Government of Norway, the Government of Spain, the European Investment Bank, the World Bank, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Health Care Systems in Transition Albania 1999 Albania II European Observatory on Health Care Systems AMS 5001891 CARE 04 01 02 Target 19 1999 Target 19 – RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE FOR HEALTH By the year 2005, all Member States should have health research, information and communication systems that better support the acquisition, effective utilization, and dissemination of knowledge to support health for all. By the year 2005, all Member States should have health research, information and communication systems that better support the acquisition, effective utilization, and dissemination of knowledge to support health for all. Keywords DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE EVALUATION STUDIES FINANCING, HEALTH HEALTH CARE REFORM HEALTH SYSTEM PLANS – organization and administration ALBANIA ISSN 1020-9077 ©European Observatory on Health Care Systems 1999 This document may be freely reviewed or abstracted, but not for commercial purposes. For rights of reproduction, in part or in whole, application should be made to the Secretariat of the European Observatory on Health Care Systems, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. -

Environmental Impacts Assessment of Chromium Minings in Bulqiza Area, Albania

ISSN 2411-958X (Print) European Journal of September-December 2017 ISSN 2411-4138 (Online) Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 3, Issue 4 Environmental Impacts Assessment of Chromium Minings in Bulqiza Area, Albania Elizabeta Susaj Enkelejda Kucaj Erald Laçi Department of Environment, Faculty of Urban Planning and Environment Management (FUPEM), University POLIS, Tirana, Albania Lush Susaj Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Faculty of Agriculture and Environment, Agricultural University of Tirana, Albania Abstract Bulqiza District is the largest chromium source, ranked fourth in the world for chrome reserves. It lays in the north-eastern part of Albania, 330-1800 m a.s.l, with 728 km² area, between 41o30’43.1N and 20o14’56.21E. There are 136 entities with chromium extraction activity and around the city of Bulqiza (2.6 km² and 13000 inhabitants), there are 33 entities. The aim of the study was the identification of the environmental state and environmental impact assessment of chromium extraction (chromite mining) and giving recommendations to minimize the negative effects of this activity. Field observations, questionnaires, chemical analysis of soil and water, meetings and interviews with central and local institutions as well as with residents were used for the realization of the study. The obtained results showed that chromium extraction causes numerous irreversible degradation of the environment in the Bulqiza area, such as the destruction of surface land layers and erosion, destruction of flora and fauna, soil and water pollution, health problems, unsustainable use and reduction of chromium reserves, etc. The inert waste that emerges after the chromium partition is discharged to the earth surface without any regularity, covering the surface of the soil and flora, leading to irreversible degradation of the environment. -

The Balkanisation of Politics: Crime and Corruption in Albania

EUI WORKING PAPERS RSCAS No. 2006/18 The Balkanisation of Politics: Crime and Corruption in Albania Daniela Irrera EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Mediterranean Programme Series 06_18.indd 1 11/05/2006 11:20:09 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES The Balkanisation of Politics: Crime and Corruption in Albania DANIELA IRRERA EUI Working Paper RSCAS No. 2006/18 BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO DI FIESOLE (FI) © 2006 Daniela Irrera This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Any additional reproduction for such purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, require the consent of the author(s), editor(s). Requests should be addressed directly to the author(s). See contact details at end of text. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. Any reproductions for other purposes require the consent of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. The author(s)/editor(s) should inform the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the EUI if the paper will be published elsewhere and also take responsibility for any consequential obligation(s). ISSN 1028-3625 Printed in Italy in May 2006 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy http://www.iue.it/RSCAS/Publications/ http://cadmus.iue.it/dspace/index.jsp Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies carries out disciplinary and interdisciplinary research in the areas of European integration and public policy in Europe. -

Health in Albania

Republic of Albania Ministry of Health Faculty of Medicine at UT HEALTH IN ALBANIA NATIONAL BACKGROUND REPORT April 2, 2009 Project: Major Consulting Report Submitted to: Tanja Knezevic E-mail: [email protected] Author(s): Mr. Genard Hajdini Consultants: Dr. Arjan Harxhi, Dr. Alban Ylli, Dr. Genci Sulçebe, Dr. Ariel Çomo, Dr. Edmond Agolli Tirana, Albania April, 2009 E-mail: [email protected] -2- TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ___________________________________________________________ 4 Introduction _________________________________________________________________ 5 1. Purpose, methodology and summary of the consultation process _____________________ 6 2. The Health S&T system in Albania_____________________________________________ 6 2.1 The Albanian Health policy framework ________________________________________ 8 2.1.1 The overall health policy framework _________________________________________ 8 2.1.2 The elements of health research policy making ________________________________ 8 2.2 Overview of health research activities__________________________________________ 9 2.2.1 Health research projects __________________________________________________ 10 2.2.2 Key competencies in health research fields ___________________________________ 11 2.2.3 Health research infrastructure_____________________________________________ 12 2.3 Key drivers of health research_______________________________________________ 13 2.3.1 Main health sector trends in Albania________________________________________ 13 2.3.2 Main socio-economic challenges -

Demographic and Health Challenges Facing Albania in the 21St Century Authorship

DEMOGRAPHIC AND HEALTH CHALLENGES FACING ALBANIA IN THE 21 CHALLENGES FACING DEMOGRAPHIC AND HEALTH DEMOGRAPHIC AND HEALTH CHALLENGES ST FACING ALBANIA CENTURY IN THE 21ST CENTURY DEMOGRAPHIC AND HEALTH CHALLENGES FACING ALBANIA IN THE 21ST CENTURY AUTHORSHIP This report is written by Dr Arjan Gjonça1, Dr Genc Burazeri2, Dr Alban Ylli3 Blerina Subashi and Rudin Hoxha4 have contributed in data provision and manipulations as well as gave feedback on the results of analyses. ISBN 978-9928-149-91-6 1 Dr Arjan Gjonça is a Professor of Demography at Department of International Development, London School of Economics and Political Science 2 Dr Genc Burazeri is a Professor of Epidemiology at Medical University of Tirana. 3 Dr Alban Ylli is a Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at Medical University of Tirana and Institute of Public Health in Albania. 4 Blerina Subashi and Rudin Hoxha are demographers/statisticians at Institute of National Statistics in Albania 2 Table of content EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................... 15 2.4. Cause-specific mortality in Albania INTRODUCTION ............................................... 17 from a regional perspective.............................. 47 2.5. Infant, Neonatal, and Child Demographic change and challenges Mortality, and the Related 1 in Albania, a regional perspective .................... 19 Causes of Death ............................................... 53 1.1. Introduction ..................................................... 20 2.5.1. Neonatal Mortality ........................................... 54 1.2. Data and methods ............................................ 20 2.5.2. Under-5 Mortality in Albania ........................... 57 1.3. Demographic transition and 2.6. Mortality and causes of death the major shift in age structure amongst children (5-18 years) of the country’s population ............................. 20 and young adults (19-29 years) ..................... -

Local Knowledge on Plants and Domestic Remedies in the Mountain Villages of Peshkopia (Eastern Albania)

J. Mt. Sci. (2014) 11(1): 180-194 e-mail: [email protected] http://jms.imde.ac.cn DOI: 10.1007/s11629-013-2651-3 Local Knowledge on Plants and Domestic Remedies in the Mountain Villages of Peshkopia (Eastern Albania) Andrea PIERONI1*, Anely NEDELCHEVA2, Avni HAJDARI3, Behxhet MUSTAFA3, Bruno SCALTRITI1, Kevin CIANFAGLIONE4, Cassandra L. QUAVE5 1 University of Gastronomic Sciences, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele 9, Pollenzo (Cuneo) I-12042, Italy 2 Department of Botany, University of Sofia, Blv. Dragan Tzankov, Sofia 1164, Bulgaria 3 Department of Biology, University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina”, Mother Teresa Str., Prishtinë 10000, Republic of Kosovo 4 School of Biosciences and Veterinary Medicine, University of Camerino, Via Pontoni 5, Camerino (Macerata) I-62032, Italy 5 Center for the Study of Human Health, Emory University, 550 Asbury Circle, Candler Library 107E, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected]; Tel: +39 0172 458575; Fax: +39 0172 458500 Citation: Pieroni A, Nedelcheva A, Hajdari A, et al. (2014) Local knowledge on plants and domestic remedies in the mountain villages of Peshkopia (Eastern Albania). Journal of Mountain Science 11(1). DOI: 10.1007/s11629-013-2651-3 © Science Press and Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, CAS and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract: Ethnobotanical studies in the Balkans are unsustainable exploitation of certain taxa (i.e. Orchis crucial for fostering sustainable rural development in and Gentiana spp.) and presents some important the region and also for investigating the dynamics of conservation challenges. Appropriate development change of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), and environmental educational frameworks should which has broad-sweeping implications for future aim to reconnect local people to the perception of biodiversity conservation efforts. -

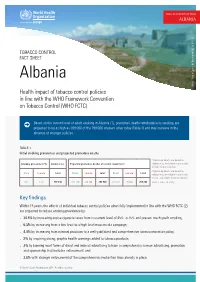

Tobacco Control Fact Sheet ALBANIA

Tobacco Control Fact Sheet ALBANIA TOBACCO CONTROL FACT SHEET Albania Photo: ‘Rozafa Castle’ by Revolution540. CC BY 2.0 Health impact of tobacco control policies in line with the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) Based on the current level of adult smoking in Albania (1), premature deaths attributable to smoking are projected to be as high as 399 000 of the 798 000 smokers alive today (Table 1) and may increase in the absence of stronger policies. TABLE 1. Initial smoking prevalence and projected premature deaths a Premature deaths are based on Smoking prevalence (%) Smokers (n) Projected premature deaths of current smokers (n) relative risks from large-scale studies of high-income countries. b Premature deaths are based on a a a b b b Male Female Total Male Female Total Male Female Total relative risks from large-scale studies of low- and middle-income countries. 58.8 11.5 797 840 332 220 66 700 398 920 215 943 43 355 259 298 Source: Ross et al (1). Key findings Within 15 years, the efects of individual tobacco control policies when fully implemented in line with the WHO FCTC (2) are projected to reduce smoking prevalence by: • 24.5% by increasing excise cigarette taxes from its current level of 45% to 75% and prevent much youth smoking; • 6.3% by increasing from a low-level to a high-level mass media campaign; • 4.4% by increasing from minimal provision to a well-publicized and comprehensive tobacco cessation policy; • 3% by requiring strong, graphic health warnings added to tobacco products; • 3% by banning most forms of direct and indirect advertising to have a comprehensive ban on advertising, promotion and sponsorship that includes enforcement; and • 2.8% with stronger enforcement of the comprehensive smoke-free laws already in place. -

Albanian Medical Journal Albanian Medical Journal

AALBANIAN mMedical journalJJ Number 3 - 2016 AALLBBAANNIIAANN MMEEDDIICCAALL JJOOUURRNNAALL R E P U B L I C O F A L B A N I A MINISTRY OF HEALTH INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC HEALTH ALBANIAN MEDICAL JOURNAL 3-2016 ALBANIAN medical journal 3-2016 ALBANIANAMJ medical journal Editors in Chief Genc Burazeri (Albania) Eduard Kakarriqi (Albania) Editorial Board (in alphabetical order) Alban Dibra (Albania) Alban Ylli (Albania) Ariel Ahart (USA) Arjan Bregu (Albania) Arjan Harxhi (Albania) Arnold D. Kaluzny (USA) Bajram Hysa (Albania) Bledar Kraja (Albania) Charles Hardy (USA) Doncho Donev (Macedonia) Enver Roshi (Albania) Ervin Toçi (Albania) Gazmend Bejtja (Albania) Gentiana Qirjako (Albania) Greg Evans (USA) Helmut Brand (The Netherlands) Ilir Alimehmetiˆ (Albania) Izet Masic (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Jera Kruja (Albania) Jolanda Hyska (Albania) Katarzyna Czabanowska (The Netherlands) Kenneth A. Rethmeier (USA) Kliti Hoti (Albania) Klodian Dhana (Albania) Klodian Rjepaj (Albania) Kreshnik Petrela (Albania) Llukan Rrumbullaku (Albania) Malcolm Whitfield (United Kingdom) Mariana Dyakova (United Kingdom) Mark Avery (Australia) Mindaugas Stankunas (Lithuania) Naim Jerliu (Kosovo) Naser Ramadani (Kosovo) Nevzat Elezi (Macedonia) Peter Schröder-Bäck (The Netherlands) Silva Bino (Albania) Suela Këlliçi (Albania) Suzanne Havala Hobbs (USA) Theodhore Tulchinsky (Israel) Tomasz Brzostek (Poland) Tony Smith (United Kingdom) Ulrich Laaser (Germany) Wlodzimierz Cezary Wlodarczyk (Poland) Zejdush Tahiri (Kosovo) Design & Layout Albanian Medical Journal Editorial Office: