Command Climate and Ethical Behavior: Perspectives from the Commandant's of the Marine Corps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer/Autumn 2004 Full Issue

Naval War College Review Volume 57 Number 3 Summer/Autumn Article 28 2004 Summer/Autumn 2004 Full Issue The U.S. Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation War College, The U.S. Naval (2004) "Summer/Autumn 2004 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 57 : No. 3 , Article 28. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol57/iss3/28 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. War College: Summer/Autumn 2004 Full Issue NAVAL WAR C OLLEGE REVIEW NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Summer/Autumn 2004 Volume LVII, Number 3/4 Summer/Autumn 2004 Summer/Autumn N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E C T I O L N L U E E G H E T I VIRIBU OR A S CT MARI VI Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2004 1 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Naval War College Review, Vol. 57 [2004], No. 3, Art. 28 Cover The Greek philosopher Aristotle (c. 384–322 BC), who by virtue of his Nichomachean Ethics is arguably the founder of ethics as a secular study, in contradistinction to the more religiously oriented moral philosophy of his teacher Plato, and of Plato’s own mentor, Socrates. -

Always a Marine” Men’S Hoodie for Me City State Zip in the Size Indicated Below As Described in This Announcement

MAGAZINE OF THE MARINES 4 1 0 2 LY U J Leathernwwew.mca-marcines.org/lekatherneck Happy Birthday, America Iraq 2004: Firefghts in the “City of Mosques” Riding With the Mounted Color Guard Settling Scores: The Battle to Take Back Guam A Publication of the Marine Corps Association & Foundation Cov1.indd 1 6/12/14 12:04 PM Welcome to Leatherneck Magazine’s Digital Edition July 2014 We hope you are continuing to enjoy the digital edition of Leatherneck with its added content and custom links to related information. Our commitment to expanding our digital offerings continues to refect progress. Also, access to added content is available via our website at www.mca- marines.org/leatherneck and you will fnd reading your Leatherneck much easier on smartphones and tablets. Our focus of effort has been on improving our offerings on the Internet, so we want to hear from you. How are we doing? Let us know at: [email protected]. Thank you for your continuing support. Semper Fidelis, Col Mary H. Reinwald, USMC (Ret) Editor How do I navigate through this digital edition? Click here. L If you need your username and password, call 1-866-622-1775. Welcome Page Single R New Style.indd 2 6/12/14 11:58 AM ALWAYS FAITHFUL. ALWAYS READY. Cov2.indd 1 6/9/14 10:31 AM JULY 2014, VOL. XCVII, No. 7 Contents LEATHERNECK—MAGAZINE OF THE MARINES FEATURES 10 The In-Between: Touring the Korean DMZ 30 100 Years Ago: Marines at Vera Cruz By Roxanne Baker By J. -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. __________ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States LAWRENCE G. HUTCHINS III, SERGEANT, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI S. BABU KAZA CHRIS G. OPRISON LtCol, USMCR DLA Piper LLP (US) THOMAS R. FRICTON 500 8th St, NW Captain, USMC Washington DC Counsel of Record Civilian Counsel for U.S. Navy-Marine Corps Petitioner Appellate Defense Division 202-664-6543 1254 Charles Morris St, SE Washington Navy Yard, D.C. 20374 202-685-7291 [email protected] i QUESTION PRESENTED In Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970), this Court held that the collateral estoppel aspect of the Double Jeopardy Clause bars a prosecution that depends on a fact necessarily decided in the defendant’s favor by an earlier acquittal. Here, the Petitioner, Sergeant Hutchins, successfully fought war crime charges at his first trial which alleged that he had conspired with his subordinate Marines to commit a killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim. The members panel (jury) specifically found Sergeant Hutchins not guilty of that aspect of the conspiracy charge, and of the corresponding overt acts and substantive offenses. The panel instead found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the lesser-included offense of conspiring to commit an unlawful killing of a named suspected insurgent leader, and found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the substantive crimes in furtherance of that specific conspiracy. After those convictions were later reversed, Sergeant Hutchins was taken to a second trial in 2015 where the Government once again alleged that the charged conspiracy agreement was for the killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim, and presented evidence of the overt acts and criminal offenses for which Sergeant Hutchins had previously been acquitted. -

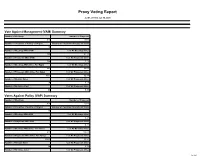

Proxy Voting Report

Proxy Voting Report Jul 01, 2019 to Jun 30, 2020 Vote Against Management (VAM) Summary Number of Meetings Number of Proposals 913 10318 Number of Countries (Country of Origin) Number of Countries (Country of Trade) 15 1 Number of Meetings With VAM % of All Meetings Voted 389 42.7% Number of Proposals With VAM % of All Proposals Voted 736 7.1% Number of Meetings With Votes For Mgmt % of All Meetings Voted 907 99.6% Number of Proposals With Votes For Mgmt % of All Proposals Voted 9551 92.8% Number of Abstain Votes % of All Proposals Voted 74 0.7% Number of No Votes Cast % of All Proposals Voted 23 0.2% Votes Against Policy (VAP) Summary Number of Meetings Number of Proposals 913 10318 Number of Countries (Country of Origin) Number of Countries (Country of Trade) 15 1 Number of Meetings With VAP % of All Meetings Voted 2 0.2% Number of Proposals With VAP % of All Proposals Voted 7 0.1% Number of Meetings With Votes For Policy % of All Meetings Voted 911 100.0% Number of Proposals With Votes For Policy % of All Proposals Voted 10288 99.9% Number of Abstain Votes % of All Proposals Voted 74 0.7% Number of No Votes Cast % of All Proposals Voted 1 of 459 23 0.2% Number of Proposals with Votes with GL % of All Proposals Voted 10166 98.8% Proposal Summary Number of Meetings: 913 Number of Mgmt Proposals: 9914 Number of Shareholder Proposals: 404 Mgmt Proposals Voted FOR % of All Mgmt Proposals ShrHldr Proposal Voted FOR % of All ShrHldr Proposals 9387 94.7% 223 55.2% Mgmt Proposals Voted Against/Withold % of All Mgmt Proposals ShrHldr Proposals -

General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., USMC MOWW OFFICERS Commander-In-Chief (CINC) MOWW ║ CINC’S Perspective Col Clifford D

JULY/AUGUST 2011 OFFICER Volume 51 ● Number 1 REVIEWTHE MILITARY ORDER OF THE WORLD WARS MOWW 2011 DISTINGUISHED SERVICE AWARD RECIPIENT General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., USMC MOWW OFFICERS Commander-in-Chief (CINC) MOWW ║ CINC’s Perspective Col Clifford D. Way, Jr. (AF) [email protected] Senior Vice BY CINC COL CLIFFORD D. WAY, JR., USAF (RETIRED) Commander-in-Chief (SVCINC) CAPT Russell C. Vowinkel (N) [email protected] I stood in a line behind 40 YLC students, ready to sign The Declaration of Independence. A speaker re- minded us that 56 representatives had earlier gathered on 4 July 1776 to sign below the same words, “And Vice Commanders-in-Chief (VCINCs) for the support of this declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutu- COL M. Hall Worthington (A) [email protected] ally pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.” LTC Gary O. Engen (A) “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, [email protected] Capt John M. Hayes (AF) that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, [email protected] Companion Mrs. Jennie McIntosh (HPM) that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” [email protected] —The DeclaraTion of inDepenDence Treasurer General LTC John H. Hollywood (A) These were not empty words. Five original signers were captured by the British as traitors and tor- [email protected] tured before they died. Twelve had their homes ran- Assistant Treasurer General sacked and burned. Two lost their sons serving in the VCINC COL M. -

Lest We Forget…

Lest we forget… Commonwealth of Kentucky Losses in the War on Terrorism (in order by date of loss) As of: 9 SEPT 15 1. Sergeant Darrin K. Potter, 24, of Louisville, Kentucky He was killed on 29 SEP 03 near Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq when his vehicle left the road and went into a canal. Potter was assigned to the 223rd Military Police Company, Kentucky Army National Guard, Louisville, Kentucky. 2. Specialist James E. Powell, 26, of Radcliff, Kentucky He was killed on 12 OCT 03 in Baji, Iraq. Powell was killed when his M2/A2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle struck an enemy anti-tank mine. He died as a result of his injuries. Powell was assigned to the Army's B Company, 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, based in Fort Hood, Texas. 3. Sergeant Michael D. Acklin II, 25, of Louisville, Kentucky He was killed on 15 NOV 03 when two 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters crashed in Mosul, Iraq. Acklin was assigned to the Army's 1st Battalion, 320th Field Artillery, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, Kentucky. 4. Corporal Gary B. Coleman, 24, of Pikeville, Kentucky He was killed on 21 NOV 03 in Balad, Iraq. Coleman was on patrol when the vehicle he was driving flipped over into a canal trapping him inside the vehicle. Coleman was assigned to the Army's B Company, 1st Battalion, 68th Armored Regiment, 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division (Mech), based in Fort Carson, Colorado. 5. Sergeant First Class James T. Hoffman, 41, of Whitesburg, Kentucky He was killed on 27 JAN 04 in an improvised explosive device attack in Khalidiyah, just east of Ar Ramadi, Iraq. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2019 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the afternoon, the President posted to his personal Twitter feed his congratulations to President Jair Messias Bolsonaro of Brazil on his Inauguration. In the evening, the President had a telephone conversation with Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel. During the day, the President had a telephone conversation with President Abdelfattah Said Elsisi of Egypt to reaffirm Egypt-U.S. relations, including the shared goals of countering terrorism and increasing regional stability, and discuss the upcoming inauguration of the Cathedral of the Nativity and the al-Fatah al-Aleem Mosque in the New Administrative Capital and other efforts to advance religious freedom in Egypt. January 2 In the afternoon, in the Situation Room, the President and Vice President Michael R. Pence participated in a briefing on border security by Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen M. Nielsen for congressional leadership. January 3 In the afternoon, the President had separate telephone conversations with Anamika "Mika" Chand-Singh, wife of Newman, CA, police officer Cpl. Ronil Singh, who was killed during a traffic stop on December 26, 2018, Newman Police Chief Randy Richardson, and Stanislaus County, CA, Sheriff Adam Christianson to praise Officer Singh's service to his fellow citizens, offer his condolences, and commend law enforcement's rapid investigation, response, and apprehension of the suspect. -

MIOSHA Strategic Plan Legal

PRST STD MITA, Michigan Infrastructure & Transportation Association U.S. POSTAGE P. O. Box 1640, Okemos, MI 48805-1640 PAID PERMIT #515 Lansing, MI Page 9 Page Legal: Avoid Fatal Mistakes Fatal Avoid Legal: Page 8 Page Regulations: MIOSHA Strategic Plan Strategic MIOSHA Regulations: Page 6 Page Safety: Know the Rules the Know Safety: FALL 2013 FALL √ √ Call MITA’s Benefi ts Consultant! association benefits company Authorized Administrator for the Michigan Infrastructure and Transportation Association’s Blue Cross® Blue Shield® of Michigan and Blue Care Network Health Insurance Program We’re the lightweights in our industry. And proud of it. At James Burg Trucking 14 years moving concrete products, brick, bagged cement, Company, our lightweight steel sheathing, and trench boxes efficiently throughout equipment can scale over Michigan, northern Ohio, 115,000 pounds. Which means northern Indiana,and Ontario. you could save time and money by reducing the number In fact, our on-time delivery of trips it takes for us to haul ratio exceeds 99%. So whether your job. We’ve been serving you need one truck for one load or twenty trucks for two the construction industry with weeks,call us. Because when it comes to superior customer Michigan flatbeds for over service and on-time delivery, we’re the heavyweights. On time. Time and again. Steve Burg, Dispatch 800.841.1289 James Burg, President 586.751.9000 Fax 586.751.1367 www.jbtc.net Active Associate Member of the MITA. FALL | 2013 comment 5 Executive Vice President Comment features 6 Vice President of Membership Services Comment 28 Vice President of Industry Relations Comment also in 8 MIOSHA Strategic Plan 39 MITA Calendar of Events this issue 9 Legal Issues 40 MITA Partner News 13 Letters to MITA 44 Legislative News 20 Member Profile 52 Member Voice 24 Associate Member Profile 54 Member Project Profile 30 Member News 56 ARTBA News 32 Summer Conference Sponsors 61 Bulletin Index 34 Golf Outing Sponsors 62 Ad Index 38 Where Has Your MITA Hat Been? Cover Photo: Cadillac Asphalt, LLC. -

Every Dollar Counts: Marines Help Local Restaurant Donate Money to Honor Flight

w Fox and November The Company graduates Friday, Jet February 27, 2015 Vol. 50, No. 8 Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, S.C. “TheStream noise you hear is the sound of freedom.” Page 11 Beaufort.Marines.mil 2 3 facebook.com/MCASBeaufort3 twitter.com/MCASBeaufortSC Marines volunteer to fight litter This is your bill New Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps posts Page 4 Pages 5 Page 6 Every dollar counts: Marines help local restaurant donate money to Honor Flight Photos by Pfc. Samantha Torres Marines and their families from Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort volunteered to help remove dollar bills stapled to the walls of a local restaurant, Feb. 21. Thousands of dol- lars were collected, and will be used to send World War II and Vietnam veterans from the Beaufort and Savannah area to visit veteran memorials in Washington, D.C., through the Honor Flight Program. The money raised provides a free trip for the veterans. Marines take care of their own and continue to do so by assisting those who came before. Voluntary Protection Program: Stay safe, be involved Pfc. Samantha Torres gram established by OSHA, to Staff Writers recognize superior performance in the field of health and safety. Marine Corps Air Station Beau- The program promotes workers’ fort strives to improve the overall safety through active and mean- safety of the Air Station by work- ingful employee involvement, ing with the Voluntary Protection and works in conjunction with Program and the Occupational the Marine Corps’ safety manage- Safety and Health Administration. ment systems. The Voluntary Protection Pro- gram is a cross functional pro- SEE VPP, PAGE 6 Reach out, help a Marine or sailor Cpl. -

Newsletter Editor: Lou Piantadosi

MC-LEF MARINE CORPS-LAW ENFORCEMENT FOUNDATION Educating the children of those who sacrificed all SEPT 2017 N E W S L E T T E R ISSUE #54 22ND ANNUAL NYC GALA 8TH ANNUAL PHILLY GATHERING OF HEROES SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 35 BOSTON MARATHON -TEAM KELLY... SEE PAGE 31 SCHOLARSHIP AWARD ARIZONA GOLF MEMBERS ON THE GO SEE PAGE 7 SEE PAGE 22 SEE PAGE 38 JACK LUCAS STORY ATLANTIC CITY GALA & GOLF FBI SCHOLARSHIPS SEE PAGE 21 SEE PAGE 10 SEE PAGE 34 FOLLOW MC-LEF www.mc-lef.org MARINE CORPS - LAW ENFORCEMENT FOUNDATION 273 Columbus Avenue • Office #10 • Tuckahoe, NY 10707 None of the MC-LEF Directors or Officers receives compensation for their services BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman Emeritus: Zachary Fisher (1910-1999) New York Vice Chairman Emeritus: Steve Wallace (1942-2010 California Chairman: James K. Kallstrom New York Vice Chairman: Gen. Peter Pace, USMC, (Ret.) North Carolina Vice Chairman: Gary Schweikert New York Marine Corps - Law Enforcement Chaplain: Monsignor Robert T. Ritchie New York Foundation DIRECTORS Mr. Sandy Alderson New York Gen. James Amos, USMC (Ret.) North Carolina Westy Ballard Texas Col. Barney Barnum, USMC (Ret.) Virginia OUR MISSION Mr. Anthony Boyle Pennsylvania Christopher Burnham Virginia LtGen. Ron S. Coleman, USMC (Ret.) Virginia The Marine Corps-Law Enforcement Mr. John Conner New York Gen. James T. Conway, 34th CMC, USMC ( Ret) Pennsylvania Foundation (MC-LEF) provides educational David Cornstein New York assistance to the children of fallen United States Mr. Ken Courey Florida Mr. Robert Cummins New York Marines and federal law enforcement personnel. -

Key Officials September 1947–July 2021

Department of Defense Key Officials September 1947–July 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Introduction 1 I. Current Department of Defense Key Officials 2 II. Secretaries of Defense 5 III. Deputy Secretaries of Defense 11 IV. Secretaries of the Military Departments 17 V. Under Secretaries and Deputy Under Secretaries of Defense 28 Research and Engineering .................................................28 Acquisition and Sustainment ..............................................30 Policy ..................................................................34 Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer ........................................37 Personnel and Readiness ..................................................40 Intelligence and Security ..................................................42 VI. Specified Officials 45 Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation ...................................45 General Counsel of the Department of Defense ..............................47 Inspector General of the Department of Defense .............................48 VII. Assistant Secretaries of Defense 50 Acquisition ..............................................................50 Health Affairs ...........................................................50 Homeland Defense and Global Security .....................................52 Indo-Pacific Security Affairs ...............................................53 International Security Affairs ..............................................54 Legislative Affairs ........................................................56