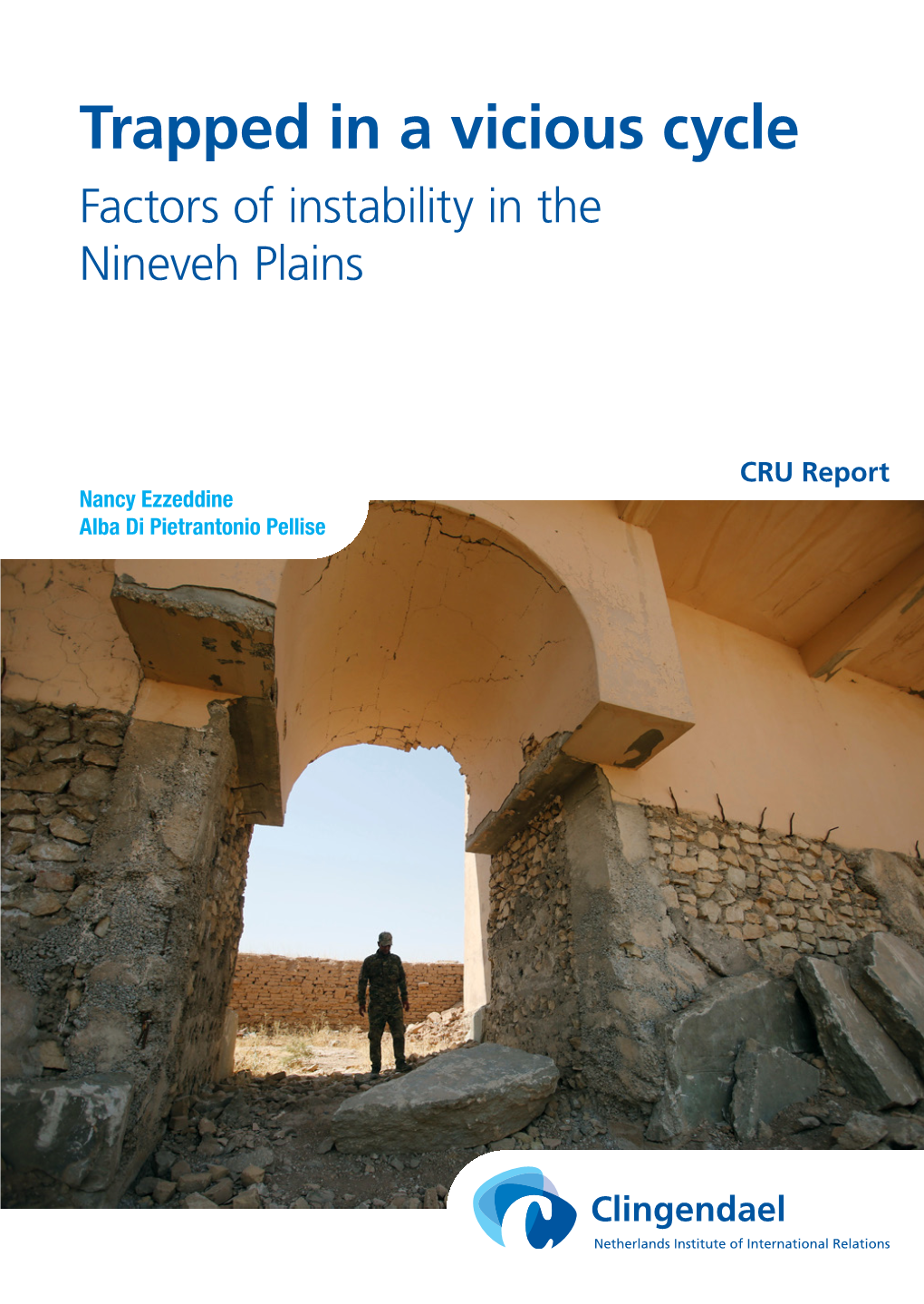

Trapped in a Vicious Cycle Factors of Instability in the Nineveh Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gurriculum Vitae

حوكمةتا هةريَما كوردستانىَ – عرياق حكومت أقليم كودستان – العراق وزارة التعليم العالي والبحث العلمي وةزراتا خوندنا باﻻ وتوذينيَت زانستى رئاست جامعت بولينكنيك دهوك سةوركاتيا زانلويا ثوليتةكنيلا دهوك Kurdistan Regional Government-Iraq Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Duhok Polytechnic University Curriculum Vitae University Address: 61 Zahko Road, 1006 Mazi Qt., Duhok , Kurdistan -Iraq A / Personal data Name: Mohammed Haydar Mosa Date of Birth: 1/1/1971 Place of Birth: Mosul City \ lraq Marital Status: Married Mother Tongue: Kurdish Other Language: Kurdish, English and Arabic Degree: M.Sc. Nursing from Nursing College/ Mosul University\ Iraq 2005 B\Educational University University Collage Degree Date (Year) Specialty Mosul Mosul Technical Technical Diploma 199 - 1993 Anesthesia Institute\Iraq Institute\Iraq Mosul College of Nursing B.SC 1994 - 1998 University Nursing Science Mosul College of Pediatric M.SC 2003 - 2005 University Nursing health nursing C\Training and education: Name ,Place , Country Type Years attended Academic degree obtained From To Tumor workshop \ Tumor 21/9/1996 - 29/9/1996 Training Mosul \Iraq nursing Second conference tumor Tumor 22/9/1996 - 24/9/1996 Training Of Mosul \Iraq Course & methods to teach public health\ Community 12 October 2004 Training Community health health nursing - 15 October 2004 nursing \ Duhok \ Iraq Cardiac catheterization Cardiac \ Azadi teaching 2007 Training catheterization hospital \Duhok\ Iraq Methods of education Methods of \Duhok Technical 4/7/2009 - 18/7/2006 education institute \Iraq Evaluation of health Environmental states At health Institutions In 7th scientific conference conference 27-28 September 2010 Iraq. Mosul proceedings university\Nursing collage The role of Scientific research in Developing 10th National scientific of public health . -

KDP and Nineveh Plain

The Kurds and the Future of Nineveh Plain (Little Assyria) Fred Aprim December 7, 2006 It puzzles me how some of our people continue to misunderstand and misinterpret the simplest of behaviors or actions on the parts of Barazani's Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and those few Assyrian individuals who speak on behalf of the Assyrian nation unlawfully. Two simple questions: 1. If Mas'aud Barazani and KDP really mean well towards Assyrians, why marginalize the biggest Assyrian political group by far, i.e., the Assyrian Democratic Movement (ADM) and exclude it from participating in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) cabinet since the ADM has been in that government since 1992 and won the only elections in northern Iraq that took place in that year. If the KDP means well, why use its influence in order to control the sole Iraqi Central Government seat that is assigned for ChaldoAssyrian Christians by having Fawzi Hariri, a KPD associate, as a minister in it. Why not act democratically and yield to the ADM that won in two national elections of January and December 2005 to fill that position? Why is it so hard to understand that Barazani is doing all this to control the Assyrians' future and cause? 2. Do the five Christian political groups, supported by KDP and its strong man Sargis Aghajan, that call for joining the Nineveh plains to the KRG, namely, a) Assyrian Patriotic Party (APP), b) ChaldoAshur Org. of Kurdistani Communist Party, c) Chaldean Democratic Forum (CDF), d) Chaldean Cultural Association (CCA), and e) Bet Nahrain Democratic Party (BNDP) really think that they will secure the Assyrian rights by simply allowing Barazani to usurp the Nineveh plain without serious guarantees recognized by the Iraqi government and international institutions. -

COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020

IRAQ COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020 The aim of this vulnerability index is to understand the capacity of camps to deal with the impact of a COVID-19 outbreak, understanding the camp as a single system composed of sub-units. The components of the index are: exposure to risk, system vulnerabilities (population and infrastructure), capacity to cope with the event and its consequences, and finally, preparedness measures. For this purpose, databases collected between August 2019 and February 2020 have been analysed, as well as interviews with camp managers (see sources next to indicators), a total of 27 indicators were selected from those databases to compose the index. For purpose of comparing the situation on the different camps, the capacity and vulnerability is calculated for each camp in the country using the arithmetic average of all the IRAQ indicators (all indicators have the same weight). Those camps with a higher value are considered to be those that need to be strengthened in order to be prepared for an outbreak of COVID-19. Each indicator, according to its relevance and relation to the humanitarian standards, has been evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 (see list of indicators and their individual assessment), with 100 being considered the most negative value with respect to the camp's capacity to deal with COVID-19. Overall Index Score (District Average*) Camp Population (District Sum) TURKEY TURKEY Zakho Zakho Al-Amadiya 46,362 Al-Amadiya 32 26 3,205 DUHOK Sumail DUHOK Sumail Al-Shikhan 83,965 Al-Shikhan Aqra -

WFP Iraq Country Brief in Numbers

WFP Iraq Country Brief In Numbers November & December 2018 6,718 mt of food assistance distributed US$9.88 m cash-based transfers made US$58.8 m 6-month (February - July 2019) net funding requirements 516,741 people assisted WFP Iraq in November & December 2018 0 49% 51% Country Brief November & December 2018 Operational Updates Operational Context Operational Updates In April 2014, WFP launched an Emergency Programme to • Returns of displaced Iraqis to their areas of origin respond to the food needs of 240,000 displaced people from continue, with more than 4 million returnees and 1.8 Anbar Governorate. The upsurge in conflict and concurrent million internally displaced persons (IDPs) as of 31 downturn in the macroeconomy continue today to increase the December (IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix). Despite poverty rate, threaten livelihoods and contribute to people’s the difficulties, 62 percent of IDPs surveyed in camp vulnerability and food insecurity, especially internally displaced settings by the REACH Multi Cluster Needs Assessment persons (IDPs), women, girls and boys. As the situation of IDPs (MCNA) VI indicated their intention to remain in the remains precarious and needs rise following the return process camps, due to lack of security, livelihoods opportunities that began in early 2018, WFP’s priorities in the country remain and services in their areas of origin. emergency assistance to IDPs, and recovery and reconstruction • Torrential rainfall affected about 32,000 people in activities for returnees. Ninewa and Salah al-Din in November 2018. Several IDP camps, roads and bridges were impacted by severe To achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in flooding, leading to a state of emergency being declared particular SDG 2 “Zero Hunger” and SDG 17 “Partnerships for the by authorities, and concerns about the long-term Goals”, WFP is working with partners to support Iraq in achieving viability of the Mosul Dam. -

Reframing Social Fragility in Iraq

REFRAMING SOCIAL FRAGILITY IN AREAS OF PROTRACTED DISPLACEMENT AND EMERGING RETURN IN IRAQ: A GUIDE FOR PROGRAMMING NADIA SIDDIQUI, ROGER GUIU, AASO AMEEN SHWAN International Organization for Migration Social Inquiry The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Cover Image: Kirkuk, Iraq, June 2016, Fragments in Kirkuk Citadel. Photo Credit: Social Inquiry. 2 Reframing Social Fragility In Areas Of Protracted Displacement And Emerging Return In Iraq Nadia Siddiqui Roger Guiu Aaso Ameen Shwan February 2017 3 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research and report were designed and written by Social Inquiry, a research group that focuses on post-conflict and fragile societies. The authors are Nadia Siddiqui, Roger Guiu, and Aaso Ameen Shwan. This work was carried out under the auspices of the International Organization for Migration’s Community Revitalization Program in Iraq and benefitted significantly from the input and support of Ashley Carl, Sara Beccaletto, Lorenza Rossi, and Igor Cvetkovski. -

Blood and Ballots the Effect of Violence on Voting Behavior in Iraq

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv DEPTARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BLOOD AND BALLOTS THE EFFECT OF VIOLENCE ON VOTING BEHAVIOR IN IRAQ Amer Naji Master’s Thesis: 30 higher education credits Programme: Master’s Programme in Political Science Date: Spring 2016 Supervisor: Andreas Bågenholm Words: 14391 Abstract Iraq is a very diverse country, both ethnically and religiously, and its political system is characterized by severe polarization along ethno-sectarian loyalties. Since 2003, the country suffered from persistent indiscriminating terrorism and communal violence. Previous literature has rarely connected violence to election in Iraq. I argue that violence is responsible for the increases of within group cohesion and distrust towards people from other groups, resulting in politicization of the ethno-sectarian identities i.e. making ethno-sectarian parties more preferable than secular ones. This study is based on a unique dataset that includes civil terror casualties one year before election, the results of the four general elections of January 30th, and December 15th, 2005, March 7th, 2010 and April 30th, 2014 as well as demographic and socioeconomic indicators on the provincial level. Employing panel data analysis, the results show that Iraqi people are sensitive to violence and it has a very negative effect on vote share of secular parties. Also, terrorism has different degrees of effect on different groups. The Sunni Arabs are the most sensitive group. They change their electoral preference in response to the level of violence. 2 Acknowledgement I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. -

Report on Iraq's Compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

Report on Iraq's Compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination SUBMITTED TO THE UN COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights (IHCHR) Baghdad 2018 1 Table of Contents Introduction: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 The Convention in Domestic Law (Articles 1, 3 & 4): ……………………………………………………………..3 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Process of democratization and Inter-Ethnic Relations (Articles 2 - 7): ……………………………..…. 3 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Effective Protection of Ethnic and Religious-Ethnic Groups against Acts of Racial Discrimination (Articles 2, 5 & 6): ………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Statistical Data Relating to the Ethnic Composition of the Population (Articles 1 & 5): ………….9 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..10 Legal Framework against Racial Discrimination (Articles 2-7): ……………………………………………. 10 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 National Human Rights Bodies to Combat Racial Discrimination (Articles 2-7): ………………….. 11 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 The Ethnic Composition of the Security and Police Services (Articles 5 & 2): ……………………… 12 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 Minority Representation in Politics (Articles 2 & 5): …………………………………………………………… 13 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Neo-Assyrian Treaties As a Source for the Historian: Bonds of Friendship, the Vigilant Subject and the Vengeful King�S Treaty

WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY Sources, Problems, and Approaches Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the University of Helsinki on September 22-25, 2014 Edited by G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger THE NEO-ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT 2019 STATE ARCHIVES OF ASSYRIA STUDIES Published by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki in association with the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Project Director Simo Parpola VOLUME XXX G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger (eds.) WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY SOURCES, PROBLEMS, AND APPROACHES THE NEO- ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT State Archives of Assyria Studies is a series of monographic studies relating to and supplementing the text editions published in the SAA series. Manuscripts are accepted in English, French and German. The responsibility for the contents of the volumes rests entirely with the authors. © 2019 by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki and the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research All Rights Reserved Published with the support of the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Set in Times The Assyrian Royal Seal emblem drawn by Dominique Collon from original Seventh Century B.C. impressions (BM 84672 and 84677) in the British Museum Cover: Assyrian scribes recording spoils of war. Wall painting in the palace of Til-Barsip. After A. Parrot, Nineveh and Babylon (Paris, 1961), fig. 348. Typesetting by G.B. Lanfranchi Cover typography by Teemu Lipasti and Mikko Heikkinen Printed in the USA ISBN-13 978-952-10-9503-0 (Volume 30) ISSN 1235-1032 (SAAS) ISSN 1798-7431 (PFFAR) CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................. vii Giovanni Battista Lanfranchi, Raija Mattila, Robert Rollinger, Introduction .............................. -

Operation Inherent Resolve Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress

OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS JANUARY 1, 2021–MARCH 31, 2021 FRONT MATTER ABOUT THIS REPORT A 2013 amendment to the Inspector General Act established the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) framework for oversight of overseas contingency operations and requires that the Lead IG submit quarterly reports to the U.S. Congress on each active operation. The Chair of the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency designated the DoD Inspector General (IG) as the Lead IG for Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). The DoS IG is the Associate IG for the operation. The USAID IG participates in oversight of the operation. The Offices of Inspector General (OIG) of the DoD, the DoS, and USAID are referred to in this report as the Lead IG agencies. Other partner agencies also contribute to oversight of OIR. The Lead IG agencies collectively carry out the Lead IG statutory responsibilities to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight of the operation. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the U.S. Government in support of the operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, investigations, or evaluations. • Report quarterly to Congress and the public on the operation and on activities of the Lead IG agencies. METHODOLOGY To produce this quarterly report, the Lead IG agencies submit requests for information to the DoD, the DoS, USAID, and other Federal agencies about OIR and related programs. The Lead IG agencies also gather data and information from other sources, including official documents, congressional testimony, policy research organizations, press conferences, think tanks, and media reports. -

The Great Mesopotamian Civilization

The Great Mesopotamian Civilization World History Dalton Hayes Ashton Poor What current nations Mesopotamia is the most closely related to Mesopotamia is most closely related to modern-day Iraq, to a lesser extant Northeastern Syria, Southeastern Turkey, and to a smaller parts of southeastern Iran. Babylon and Nineveh Babylon and Nineveh were located next to rivers for trade. Important Mesopotamian cities • Babylon, Nineveh. • Babylon was destroyed in 689 B.C. And then was rebuilt. • Sargon II the emperor of Nineveh died in battle and Sennacherib took royal seat. • City was famous for its temples. Babylon • Babylon a ancient city of Mesopotamia is one of the most important cities of the Middle East. It was located on the Euphrates river and North of the cities that flourished in South Mesopotamia. • Babylon was destroyed in 689 B.C and later on was rebuilt. Babylon before and after The one on the left is when Babylon got destroyed. The one on the right is when Babylon was rebuilt. Ziggurats the place for religion Ziggurats are, equally alike to a pyramid but are not tombs. They are temples they were built in the Seleucid age. Ziggurats were used for religion and the study of the Mesopotamian religion. Religion of the Mesopotamians • The inner city temples were the place of god plus the palace of the ruler. • The city of Nineveh was famous for its temples Ištar temple and Nabu temple. • They worshiped a goddess named Ištar. • Mesopotamia is a polytheistic religion Nineveh Was famous for there temples. A Early City • A early city (and subsequent buildings) were built on a fault line and suffered damages from multiple earthquakes.