Constructing and Performing the Odissi Body: Ideologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

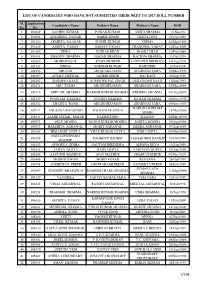

List of Candidates Who Have Not Submitted Their Neet Ug 2017 Roll Number

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE NOT SUBMITTED THEIR NEET UG 2017 ROLL NUMBER Sl. Application Candidate's Name Father's Name Mother's Name DOB No. No. 1 100249 SACHIN KUMAR PAWAN KUMAR ANITA SHARMA 15.Nov.93 2 100808 ANUSHEEL NAGAR OMBIR SINGH GEETA DEVI 07/Oct/1998 3 101222 AKSHITA DAAGAR SUSHIL KUMAR SEEMA 24/May/1999 4 101469 ANKITA YADAV SANJAY YADAV CHANCHAL YADAV 31/Dec/1999 5 101593 ZEWA NAWAB KHAN NOOR JAHAN 10/Feb/1999 6 101814 SHAGUN SHARMA GAGAN SHARMA RACHNA SHARMA 13/Oct/1998 7 102087 MOHD FAISAL SHAHABUDDIN JANNATUL FIRDOUS 14/Aug/1998 8 102121 SNEHA SOBODH KUMAR RAJENDRI 20/Jul/1998 9 102256 ABUZAR MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 10 102397 ANJALI DESWAL JAGBIR SINGH RAJ RANI 05/Sep/1998 11 102402 RASMEET KAUR SURINDER PAL SINGH GURVINDER KAUR 11/Sep/1997 12 102474 ABU TALHA MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 13 102515 SHIVANI SHARMA RAKESH KUMAR SHARMA KRISHNA SHARMA 01/Aug/2000 14 102529 POONAM SHARMA GOVIND SHARMA RAJESH SHARMA 04/Nov/1998 15 102532 SHAISTA BANO MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 09/Nov/1997 KARUNA KUMARI 16 102711 ANUSHKA RAJ SINGH RAJ KUMAR SINGH 12/Mar/2000 SINGH 17 102841 AAMIR SUHAIL MALIK NASIMUDDIN SHANNO 26/May/1996 18 102971 ABLE MOGHA MANOJ KUMAR MOGHA SARITA MOGHA 19/Aug/1998 19 103053 HARSHITA AGRAWAL MOHIT AGRAWAL MEERA AGRAWAL 07/Sep/1999 20 103245 HIMANSHI GUPTA VIJAY KUMAR GUPTA INDU GUPTA 09/May/2000 NGULLIENTHANG 21 103428 PAOKHUP HAOKIP VANKHOMOI HAOKIP 03/Oct/1998 HAOKIP 22 103433 APOORVA SINHA GAUTAM BIRENDRA ALPANA DEVA 12/Sep/1999 23 103518 TANYA GUPTA RAJIV GUPTA VANDANA GUPTA 29/Apr/1999 -

Model Queastion Bank for C G JE

QUESTION PAPER FOR THE WRITTEN TEST FOR TIIE POST OF JUNIOR ENGINEER(IvIECHANICAL) ON COMPASSIONATE GROLJND DIVISION: KUR , Date of Exam : 20. 10.2020 Total marks : : 150 Marks There are 4 sections in the question paper : - SECTION-'I' is carrying 20 marks - SECTION-'ll' is carrying 20 marks SECTION-'lll' is carrying 20 marks SECTION -'lV' is carrying 90 marks Total t7 a Total Time : 02.00 hrs sEcTtoN _ I IGENERAI AWARENESS) (Questlon no. 01 to 20 Carry one mark each) Choose the correct answer from the given optlons: 1) World Environment Day is celebrated on _. mqq+fl crfads_q{ffarlrqrfl tl a) 5th June b) 6th July c) 7th August d) 8th september qs{f, fioa-arg fr)73l-JrF strfrdcr 2) 'Thimphu'is the Gpital of frT 6I {rfirrfr tt a) Meghalaya b) Bhutan c) Manipur d) Sikkim (r)tsrdq dDqc'a OaFrg{ Ofrfuq 3) 'Sabarimala' is located in which of the following state? ,rstrErilffifud ue| 4 g frs f Fra tz a) Tamilnadu b) Kerala c) Karnataka d) Telengana qaft-d-dE Oi-rfr Os-dl-.6 SDAiirrm 4l How many fundamental rights are mentioned in lndian constitution? firc&q tfqra d' fuili dft-fi 3rfusr fir rrds ft.qr erqr t, a) Five b) Six c) Seven d) Eight 9crE fie-a dr)sra dDsn6 Page 1 of 17 5) Total number of districts in Odisha is _. 3i&n$ ffi 6r Ea,iwr_-g; al L7 b) 2s c) 30 d) 33 6) Which of the following is no longer a planet in our solar system? FeafrE-a d t dt-fr €rf,qrt dt{ asa fr rrfafi.t: a) Mercury b) Mars c) Neptune d) pluto (r)gq Oaa-n OAE-qd Oqi) 7) 'Mona Lisa' painting was made by _. -

Odissi Dance

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2005 ODISSI DANCE Photo Courtesy : Introduction : KNM Foundation, BBSR Odissi dance got its recognition as a classical dance, after Bharat Natyam, Kathak & Kathakali in the year 1958, although it had a glorious past. The temple like Konark have kept alive this ancient forms of dance in the stone-carved damsels with their unique lusture, posture and gesture. In the temple of Lord Jagannath it is the devadasis, who were performing this dance regularly before Lord Jagannath, the Lord of the Universe. After the introduction of the Gita Govinda, the love theme of Lordess Radha and Lord Krishna, the devadasis performed abhinaya with different Bhavas & Rasas. The Gotipua system of dance was performed by young boys dressed as girls. During the period of Ray Ramananda, the Governor of Raj Mahendri the Gotipua style was kept alive and attained popularity. The different items of the Odissi dance style are Mangalacharan, Batu Nrutya or Sthayi Nrutya, Pallavi, Abhinaya & Mokhya. Starting from Mangalacharan, it ends in Mokhya. The songs are based upon the writings of poets who adored Lordess Radha and Krishna, as their ISTHADEVA & DEVIS, above all KRUSHNA LILA or ŎRASALILAŏ are Banamali, Upendra Bhanja, Kabi Surya Baladev Rath, Gopal Krishna, Jayadev & Vidagdha Kavi Abhimanyu Samant Singhar. ODISSI DANCE RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE CLASSICAL DANCE FORM Press Comments :±08-04-58 STATESMAN őIt was fit occasion for Mrs. Indrani Rehman to dance on the very day on which the Sangeet Natak Akademy officially recognised Orissi dancing -

Some Thoughts on Odissi Dance*

Some Thoughts on Odis si Dance* DlNANA TH PATRY J. TH EO BSESS ION WIT H CLASS iCiSM n the Indian context there is nothing called classicism. The Sanskr it word shastriya, I which is generally believed to be a translation of'classic' or 'the classical', represents a misunderstanding ofboth the words. 'classicism' and shastriya. A shastra is a written text, a codified version of the practices of a given period which tri es to claim an authority in a subsequent period oflime. Dependence on the practice (prayoga) and later on the textual prescription becomes a tradi tion (jJarampara) with the peopl e who follo w it. While the shastra or the text remains constant, the practices that form the tradition become variables. Therefore, a need arises to write different texts in different periods oftime. To comprehend and contexrualize the variables in textual codifications, scholars resort to new interpreta· tions (commentaries) and such attempts finally emb ody regional aspirations. While there is a basic text like Narya Shastra, there are oth er texts like Nartananimaya I. Nartananim aya is a remarkable work in that it marks a transiti on al point in the evolution of dance in India. In contrast with its prec ursors in the field. which follow in the main the descriptions of danc es given by Bharata in Natya Shastra, the Nartananimaya describes entirely new forms. These new forms were shaped by regional styles that were not included. though their existence was acknowledged by Bharata, wh ich was term ed by his successors marga, that is, the main path . -

List of Ccrt Scholarship Holders for the Year 2015-2016

LIST OF CCRT SCHOLARSHIP HOLDERS FOR THE YEAR 2015-2016 NAME OF SCHOLAR AUTHORISED PARENT S.NO. FILE NO. FIELD OF TRAINING HOLDER NAME/GUARDIAN NAME 1. SCHO/2015-16/00001 TRISHA BHATTACHARJEE TARUN BHATTACHARJEE FOLK SONGS HINDUSTANI MUSIC 2. SCHO/2015-16/00003 ALIK CHAUDHURI TANMAY CHAUDHURI VOCAL HINDUSTANI MUSIC 3. SCHO/2015-16/00004 DEBJANI NANDI CHANDAN NANDI VOCAL HINDUSTANI MUSIC 4. SCHO/2015-16/00005 SATTWIK CHAKRABORTY SUPRIYO CHAKRABORTY VOCAL HINDUSTANI MUSIC 5. SCHO/2015-16/00006 SANTANU SAHA GAUTAM SAHA VOCAL 6. SCHO/2015-16/00008 SUPTAKALI CHAUDHURI PREMANKUR CHAUDHORI RABINDRA SANGEET 7. SCHO/2015-16/00009 SUBHAYO DAS KAJAL KUMAR DAS RABINDRA SANGEET 8. SCHO/2015-16/00010 ANUVA ROY ASHIS ROY NAZRUL GEETI 9. SCHO/2015-16/00011 PLABAN NAG PRADIP NAG NAZRUL GEETI 10. SCHO/2015-16/00012 SURAJIT DEB KRISHNA BANDHU DEB GHAZAL HINDUSTANI MUSIC 11. SCHO/2015-16/00014 BARSHA DAS BANKIM CHANDRA DAS INSTRUMENT-GUITAR HINDUSTANI MUSIC 12. SCHO/2015-16/00016 ABHIGNAN SAHA GOPESH CHANDRA SAHA INSTRUMENT-TABLA 13. SCHO/2015-16/00017 DEBOLINA DEBNATH DWIJOTTAM DEBNATH HINDUSTANI MUSIC INSTRUMENT-VIOLIN 14. SCHO/2015-16/00020 BINDIYA SINGHA RAMENDRA SINGHA MANIPURI DANCE 15. SCHO/2015-16/00022 BARNITA CHOUDHURY NILADRI CHOUDHURY KATHAK 16. SCHO/2015-16/00023 ADWITIYA DEB ROY ASHISH DEBROY KATHAK 17. SCHO/2015-16/00024 SOUMYADEEP DEB SUSANTA CH. DEB KATHAK 18. SCHO/2015-16/00025 NUPUR SINHA PRADIP SINHA MANIPURI DANCE 19. SCHO/2015-16/00026 MONALISHA SINGHA BISWAJIT SINGHA MANIPURI DANCE 20. SCHO/2015-16/00027 RISHA CHOWDHURY RANA CHOWDHOURY BHARATNATAYAM 21. SCHO/2015-16/00028 NAYAN SAHA NANTURANJAN SAHA PAINTING 22. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Bharatanatyam: Eroticism, Devotion, and a Return to Tradition

BHARATANATYAM: EROTICISM, DEVOTION, AND A RETURN TO TRADITION A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Taylor Steine May/2016 Page 1! of 34! Abstract The classical Indian dance style of Bharatanatyam evolved out of the sadir dance of the devadāsīs. Through the colonial period, the dance style underwent major changes and continues to evolve today. This paper aims to examine the elements of eroticism and devotion within both the sadir dance style and the contemporary Bharatanatyam. The erotic is viewed as a religious path to devotion and salvation in the Hindu religion and I will analyze why this eroticism is seen as religious and what makes it so vital to understanding and connecting with the divine, especially through the embodied practices of religious dance. Introduction Bharatanatyam is an Indian dance style that evolved from the sadir dance of devadāsīs. Sadir has been popular since roughly the 6th century. The original sadir dance form most likely originated in the area of Tamil Nadu in southern India and was used in part for temple rituals. Because of this connection to the ancient sadir dance, Bharatanatyam has historic traditional value. It began as a dance style performed in temples as ritual devotion to the gods. This original form of the style performed by the devadāsīs was inherently religious, as devadāsīs were women employed by the temple specifically to perform religious texts for the deities and for devotees. Because some sadir pieces were dances based on poems about kings and not deities, secularism does have a place in the dance form. -

A History of Legal and Moral Regulation of Temple Dance in India

Naveiñ Reet: Nordic Journal of Law and Social Research (NNJLSR) No.6 2015, pp. 131-148 Dancing Through Laws: A History of Legal and Moral Regulation of Temple Dance in India Stine Simonsen Puri Introduction In 1947, in the state of Tamil Nadu in South India, an Act was passed, “The Tamil Nadu Devadasis (Prevention of Dedication) Act,” which among other things banned the dancing of women in front of Hindu temples. The Act was to target prostitution among the so-called devadasis that were working as performers within and beyond Hindu temples, and who, according to custom also were ritually married or dedicated to temple gods. The Act was the culmination of decades of public and legal debates centred on devadasis, who had come to symbolize what was considered a degenerated position of women within Hindu society. Concurrent with this debate, the dance of the devadasis which had developed through centuries was revived and reconfigured among the Indian upper class; and eventually declared one of Indian national dances, called bharatanatyam (which can translate as Indian dance). Today, while parts of the devadasi tradition have been banned, bharatanatyam is a popular activity for young girls and women among the urban middle and upper classes in all parts of India. The aim of this article is to examine moral boundaries tied to the female moving body in India. I do so by looking into the ways in which the regulation of a certain kind of dancers has framed the moral boundaries for contemporary young bharatanatyam dancers. A focus on legal and moral interventions in dance highlights the contested role of the female body in terms of gender roles, religious ideology, and moral economy. -

The Role of Indian Dances on Indian Culture

www.ijemr.net ISSN (ONLINE): 2250-0758, ISSN (PRINT): 2394-6962 Volume-7, Issue-2, March-April 2017 International Journal of Engineering and Management Research Page Number: 550-559 The Role of Indian Dances on Indian Culture Lavanya Rayapureddy1, Ramesh Rayapureddy2 1MBA, I year, Mallareddy Engineering College for WomenMaisammaguda, Dhulapally, Secunderabad, INDIA 2Civil Contractor, Shapoor Nagar, Hyderabad, INDIA ABSTRACT singers in arias. The dancer's gestures mirror the attitudes of Dances in traditional Indian culture permeated all life throughout the visible universe and the human soul. facets of life, but its outstanding function was to give symbolic expression to abstract religious ideas. The close relationship Keywords--Dance, Classical Dance, Indian Culture, between dance and religion began very early in Hindu Wisdom of Vedas, etc. thought, and numerous references to dance include descriptions of its performance in both secular and religious contexts. This combination of religious and secular art is reflected in the field of temple sculpture, where the strictly I. OVERVIEW OF INDIAN CULTURE iconographic representation of deities often appears side-by- AND IMPACT OF DANCES ON INDIAN side with the depiction of secular themes. Dancing, as CULTURE understood in India, is not a mere spectacle or entertainment, but a representation, by means of gestures, of stories of gods and heroes—thus displaying a theme, not the dancer. According to Hindu Mythology, dance is believed Classical dance and theater constituted the exoteric to be a creation of Brahma. It is said that Lord Brahma worldwide counterpart of the esoteric wisdom of the Vedas. inspired the sage Bharat Muni to write the Natyashastra – a The tradition of dance uses the technique of Sanskrit treatise on performing arts. -

Search a Journal of Arts, Humanities & Management Vol-IX, Issue-1 January, 2015

search A Journal of Arts, Humanities & Management Vol-IX, Issue-1 January, 2015 DDCE Education for All DDCE, UTKAL UNIVERSITY, BHUBANESWAR, INDIA Prof. S. P. Pani, Director,DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. Dr. M. R. Behera Lecturer in Oriya, DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. Dr. Sujit K. Acharya Lecturer in Business Administration DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. Dr. P. P. Panigrahi Executive Editor Lecturer in English, DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. ISSN 0974-5416 Copyright : © DDCE, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar Authors bear responsibility for the contents and views expressed by them. Directorate of Distance & Continuing Education, Utkal University does not bear any responsibility. Published by : Director, Directorate of Distance & Continuing Education, Utkal University, Vanivihar, Bhubaneswar – 751007. India. Reach us at E-mail : [email protected]. 91-674 –2376700/2376703(O) Type Setting & Printing: CAD 442, Saheed Nagar Bhubaneswar - 751 007 Ph.: 0674-2544631, 2547731 ii History is TRUTH and TRUTH is God. History is a search for the ultimate truth , an understanding which would end the search for any further explanation. Many of you may feel disturbed with such a content. In fact, many of you may feel this statement to be very subjective. Indeed you may opine that history is all about alternative explanations, choice of one explanation over the others with justification. In this short editorial an attempt is being made to explore, ‘History as Truth’. History like any other discipline can never be dealt in isolation; however, it may seem so. It is not even a distinct part of the whole, it is indeed the whole itself- both temporally and spatially. Why all search in history may be partial yet the partial search always can be of the whole only.