Blasphemy, the Fate of Ahmadiyya in Lombok and a Critique of Religious Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penjor in Hindu Communities

Penjor in Hindu Communities: A symbolic phrases of relations between human to human, to environment, and to God Makna penjor bagi Masyarakat Hindu: Kompleksitas ungkapan simbolis manusia kepada sesama, lingkungan, dan Tuhan I Gst. Pt. Bagus Suka Arjawa1* & I Gst. Agung Mas Rwa Jayantiari2 1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Udayana 2Faculty of Law, Universitas Udayana Address: Jalan Raya Kampus Unud Jimbaran, South Kuta, Badung, Bali 80361 E-mail: [email protected]* & [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this article was to observe the development of the social meaning derived from penjor (bamboo decorated with flowers as an expression of thanks to God) for the Balinese Hindus. In the beginning, the meaning of penjor serves as a symbol of Mount Agung, and it developed as a human wisdom symbol. This research was conducted in Badung and Tabanan Regency, Bali using a qualitative method. The time scope of this research was not only on the Galungan and Kuningan holy days, where the penjor most commonly used in society. It also used on the other holy days, including when people hold the caru (offerings to the holy sacrifice) ceremony, in the temple, or any other ceremonial place and it is also displayed at competition events. The methods used were hermeneutics and verstehen. These methods served as a tool for the researcher to use to interpret both the phenomena and sentences involved. The results of this research show that the penjor has various meanings. It does not only serve as a symbol of Mount Agung and human wisdom; and it also symbolizes gratefulness because of God’s generosity and human happiness and cheerfulness. -

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2000 Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Rangoon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Fischer, Joseph, "Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries" (2000). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 803. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/803 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Vanishing Balinese embroideries provide local people with a direct means of honoring their gods and transmitting important parts of their narrative cultural heritage, especially themes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. These epics contain all the heroes, preferred and disdained personality traits, customary morals, instructive folk tales, and real and mythic historic connections with the Balinese people and their rich culture. A long ider-ider embroidery hanging engagingly from the eaves of a Hindu temple depicts supreme gods such as Wisnu and Siwa or the great mythic heroes such as Arjuna and Hanuman. It connects for the Balinese faithful, their life on earth with their heavenly tradition. Displayed as an offering on outdoor family shrines, a smalllamak embroidery of much admired personages such as Rama, Sita, Krisna and Bima reflects the high esteem in which many Balinese hold them up as role models of love, fidelity, bravery or wisdom. -

Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: Effects of Altitude, the 1815 Cataclysmic Volcanic Eruption and Trade

FORKTAIL 18 (2002): 49–61 Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: effects of altitude, the 1815 cataclysmic volcanic eruption and trade COLIN R. TRAINOR In June-July 2000, a 10-day avifaunal survey on Gunung Tambora (2,850 m, site of the greatest volcanic eruption in recorded history), revealed an extraordinary mountain with a rather ordinary Sumbawan avifauna: low in total species number, with all species except two oriental montane specialists (Sunda Bush Warbler Cettia vulcania and Lesser Shortwing Brachypteryx leucophrys) occurring widely elsewhere on Sumbawa. Only 11 of 19 restricted-range bird species known for Sumbawa were recorded, with several exceptional absences speculated to result from the eruption. These included: Flores Green Pigeon Treron floris, Russet-capped Tesia Tesia everetti, Bare-throated Whistler Pachycephala nudigula, Flame-breasted Sunbird Nectarinia solaris, Yellow-browed White- eye Lophozosterops superciliaris and Scaly-crowned Honeyeater Lichmera lombokia. All 11 resticted- range species occurred at 1,200-1,600 m, and ten were found above 1,600 m, highlighting the conservation significance of hill and montane habitat. Populations of the Yellow-crested Cockatoo Cacatua sulphurea, Hill Myna Gracula religiosa, Chestnut-backed Thrush Zoothera dohertyi and Chestnut-capped Thrush Zoothera interpres have been greatly reduced by bird trade and hunting in the Tambora Important Bird Area, as has occurred through much of Nusa Tenggara. ‘in its fury, the eruption spared, of the inhabitants, not a although in other places some vegetation had re- single person, of the fauna, not a worm, of the flora, not a established (Vetter 1820 quoted in de Jong Boers 1995). blade of grass’ Francis (1831) in de Jong Boers (1995), Nine years after the eruption the former kingdoms of referring to the 1815 Tambora eruption. -

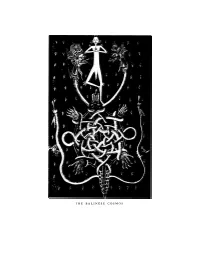

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Ethnobotanical Study on Local Cuisine of the Sasak Tribe in Lombok Island, Indonesia

J Ethn Foods - (2016) 1e12 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnic Foods journal homepage: http://journalofethnicfoods.net Original article Ethnobotanical study on local cuisine of the Sasak tribe in Lombok Island, Indonesia * Kurniasih Sukenti a, , Luchman Hakim b, Serafinah Indriyani b, Y. Purwanto c, Peter J. Matthews d a Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Mataram University, Mataram, Indonesia b Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia c Laboratory of Ethnobotany, Division of Botany, Biology Research Center-Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Indonesia d Department of Social Research, National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, Japan article info abstract Article history: Background: An ethnobotanical study on local cuisine of Sasak tribe in Lombok Island was carried out, as Received 4 April 2016 a kind of effort of providing written record of culinary culture in some region of Indonesia. The cuisine Received in revised form studied included meals, snacks, and beverages that have been consumed by Sasak people from gener- 1 August 2016 ation to generation. Accepted 8 August 2016 Objective: The aims of this study are to explore the local knowledge in utilising and managing plants Available online xxx resources in Sasak cuisine, and to analyze the perceptions and concepts related to food and eating of Sasak people. Keywords: ethnobotany Methods: Data were collected through direct observation, participatory-observation, interviews and local cuisine literature review. Lombok Results: In total 151 types of consumption were recorded, consisting of 69 meals, 71 snacks, and 11 Sasak tribe beverages. These were prepared with 111 plants species belonging to 91 genera and 43 families. -

Pakistan Uscirf–Recommended for Countries of Particular Concern (Cpc)

PAKISTAN USCIRF–RECOMMENDED FOR COUNTRIES OF PARTICULAR CONCERN (CPC) KEY FINDINGS n 2019, religious freedom conditions across Pakistan continued to loudspeaker that the community had insulted Islam. In another inci- trend negatively. The systematic enforcement of blasphemy and dent, nearly 200 Christian families in Karachi were forced to flee their Ianti-Ahmadiyya laws, and authorities’ failure to address forced homes due to mob attacks after false blasphemy accusations against conversions of religious minorities—including Hindus, Christians, four Christian women. and Sikhs—to Islam, severely restricted freedom of religion or belief. Ahmadi Muslims, with their faith essentially criminalized, con- While there were high-profile acquittals, the blasphemy law tinued to face severe persecution from authorities as well as societal remained in effect. USCIRF is aware of nearly 80 individuals who harassment due to their beliefs, with both the authorities and mobs remained imprisoned for blasphemy, with at least half facing a life targeting their houses of worship. In October, for example, police sentence or death. After spending five years in solitary confinement partially demolished a 70-year-old Ahmadiyya mosque in Punjab. for allegedly posting blasphemous content online, Junaid Hafeez In Hindu, Christian, and Sikh communities, young women, often was given the death sentence in December 2019. Many ongoing underage, continued to be kidnapped for forced conversion to Islam. trials related to blasphemy experienced lengthy delays as cases Several independent institutions estimated that 1,000 women are were moved between judges. Moreover, these laws create a cul- forcibly converted to Islam each year; many are kidnapped, forcibly ture of impunity for violent attacks following accusations. -

Folklore As a Tool to Naturally Learn and Maintain Sasak Language As Mother Tongue

Folklore as a Tool to Naturally Learn and Maintain Sasak Language as Mother Tongue Nuriadi Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, University of Mataram, Majapahit Street No.62, Mataram Keywords: Folklore, Maintenance, Sasak Language, Mother Tongue. Abstract: This paper discusses the role of function of Sasak folklore, especially verbal folklores, in teaching and maintaining Sasak language naturally. ‘Sasak’ is a name of an ethnic group exisiting in Lombok island using Sasak language as mother tongue. Based on qualitative research, Sasak people is usually ‘planting’ (teaching) the Sasak language as their mother tongue through folklore, especially verbal Sasak folklores. Those are such as: pinje panje, children playing songs (elate), lullabying songs (bedede), or story telling (waran). This activity mostly happens in informal form in any kind of occasions. This phenomenon is usually undergone by mothers to their children or by other children to their friends in their own communities. Hence, it is also found that this model of learning is very effective in maintaining the Sasak language as mother tongue and Sasak culture. Finally, based on the research, most of the informants acknowledge that they still well remember all the folklores they played in childhood. They even still love their Sasak backgrounds. Therefore, Sasak folklore is a good tool in naturally teaching and/or maintaining Sasak language. 1 INTRODUCTION taking a role as mother-tongue for that group. It is embedded, according to Sairin (2010), in the vein of Language is as a culture and identity as well for each the real users and functions as a determinant of ethnic group (Sairin, 2010). -

FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia)

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia) Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and indigenous communities across the world are 126 countries, the winners were recognized for their advancing innovative sustainable development solutions achievements at a prize ceremony held in conjunction that work for people and for nature. Few publications with the United Nations Convention on Climate Change or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives (COP21) in Paris. Special emphasis was placed on the evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change protection, restoration, and sustainable management over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories of forests; securing and protecting rights to communal with community practitioners themselves guiding the lands, territories, and natural resources; community- narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. based adaptation to climate change; and activism for The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding environmental justice. The following case study is one in from the Government of Norway, awarded the Equator a growing series that describes vetted and peer-reviewed Prize 2015 to 21 outstanding local community and best practices intended to inspire the policy dialogue indigenous peoples initiatives to reduce poverty, protect needed to take local success to scale, to improve the global nature, and strengthen resilience in the face of climate knowledge base on local environment and development change. Selected from 1,461 nominations from across solutions, and to serve as models for replication. -

12628 Seramasara 2020 E .Docx

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 12, Issue 6, 2020 Wetu Telu as a Local Identity of the Sasak ethnic Group on Globally Cultural Endeavour in Lombok I Gusti Ngurah Seramasaraa, Email: [email protected], This paper aims to examine the Wetu Telu as the local identity of Sasak ethnic group on globally cultural endeavour in Lombok. The Wetu Telu tradition has been inherited down from many generations by Sasak ethnic groups, and has experienced a cultural endeavour in the era of globalisation, because it was considered not in accordance with the teachings of Islam in general. The endeavour arises between the ethnic Sasak group who want to maintain the Wetu Telu tradition as a local identity and those who want to apply Islamic culture in general. The endeavour raises concerns about the extinction of the Wetu Telu tradition and the Sasak ethnic group losing their identity. The issue that arises in this case is how Sasak people can maintain their local wisdom so as not to lose their identity. To analyse and explain the Wetu Telu culture as a local identity of the Sasak ethnicity, qualitative research methods were used to reveal the Wetu Telu cultural meaning as a Sasak identity and explain the rise of Sasak local wisdom in Lombok in the midst of globalisation. Qualitative research methods in this case use the historical paradigm, the theory of multiculturalism and the theory of hegemony. This research will be able to reveal the background of the Wetu Telu culture, the endeavour of identity and the rise of the Wetu Telu as the Sasak identity. -

Maintaining Social Relationship of Balinese and Sasak Ethnic Community

International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Available online at http://sciencescholar.us/journal/index.php/ijssh Vol. 2 No. 1, April 2018, pages: 92~104 e-ISSN: 2550-7001, p-ISSN: 2550-701X http://dx.doi.org/10.29332/ijssh.v2n1.96 Maintaining Social Relationship of Balinese and Sasak Ethnic Community I Wayan Ardhi Wirawan a Article history: Received 20 August 2017, Accepted in revised form 25 January 2018, Approved 11 February 2018, Available online 9 March 2018 Correspondence Author a Abstract This research aims to study the background of building informal cultural ties as a medium of reharmonization between Balinese ethnic community and Sasak ethnic community in Mataram City, West Nusa Tenggara Province. This study used qualitative interpretive design in order to find answers issues, namely background of establishing a cohesion bond between two ethnic communities. Based on the result of this research, it is found that there are four influential factors, namely cultural contact between Balinese ethnic and Sasak ethnic communities during the historic period, the implementation of Balinese culture and Sasak culture in Lombok, cultural adaptation of each cultural identity, and construction of informal cultural ties as medium of interethnic communication. Keywords The informal cultural ties have an important significance in maintaining the integration between Balinese ethnic community and the Sasak ethnic Ethnic balinese; community in Mataram city. Based on this phenomenon, the recommendation Informal cultural ties; that can be proposed is to maintain the sustainability of informal cultural ties Quotidian; through the cultivation of awareness in each ethnic community and Sasak ethnic; involvement of traditional figures in providing intensive guidance on the Social harmony; importance of preserving the cultural values of ancestral heritage in maintaining social harmony. -

Welcome to Ahmadiyyat, the True Islam− Ð Õ Êáîyj»A Æ Ê Ì Êåày Æ J»Aì Êé¼»A Ániê Æ Ê

Welcome to Ahmadiyyat, The True Islam− Ð Õ êÁÎYj»A æ ê ì êÅÀY æ j»Aì êɼ»A ÁnIê æ ê In the name of Allah,− the Gracious, the Merciful WELCOME TO AHMADIYYAT, THE TRUE ISLAM TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword: Sahibzada± − ± − M. M. Ahmad,± Amir− Jama‘at,− USA 11 Introduction ............................................................................. 13 System of Transliteration ............................................................ 15 Publisher's Note ......................................................................... 17 1 The Purpose of Man's Life ..................................... 19 Means of Attaining Purpose of Life ........................... 24 Significance of Religion ............................................ 28 The Continuity of Religion ........................................ 29 The Apex of Religious Development ......................... 31 Unity of Religions ..................................................... 31 2 Islam− and a Muslim ................................................. 32 Unification of Humanity Through Islam− ................... 44 Ahmadi± − Muslims ....................................................... 50 1 Welcome to Ahmadiyyat, The True Islam− 3 The Islamic− Beliefs (The Articles of Faith) ......... 52 Unity of Allah− ............................................................ 54 The Islamic− Concept of God Almighty ...................... 55 God's Attributes (Divine Names) ........................ 61 Angels ........................................................................ 64 The Islamic−