NASA Technology Roadmaps TA 3: Space Power and Energy Storage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Energy in the 21St Century: a Primer

U.S. Energy in the 21st Century: A Primer March 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46723 SUMMARY R46723 U.S. Energy in the 21st Century: A Primer March 16, 2021 Since the start of the 21st century, the U.S. energy system has changed tremendously. Technological advances in energy production have driven changes in energy consumption, and Melissa N. Diaz, the United States has moved from being a net importer of most forms of energy to a declining Coordinator importer—and a net exporter in 2019. The United States remains the second largest producer and Analyst in Energy Policy consumer of energy in the world, behind China. Overall energy consumption in the United States has held relatively steady since 2000, while the mix of energy sources has changed. Between 2000 and 2019, consumption of natural gas and renewable energy increased, while oil and nuclear power were relatively flat and coal decreased. In the same period, production of oil, natural gas, and renewables increased, while nuclear power was relatively flat and coal decreased. Overall energy production increased by 42% over the same period. Increases in the production of oil and natural gas are due in part to technological improvements in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling that have facilitated access to resources in unconventional formations (e.g., shale). U.S. oil production (including natural gas liquids and crude oil) and natural gas production hit record highs in 2019. The United States is the largest producer of natural gas, a net exporter, and the largest consumer. Oil, natural gas, and other liquid fuels depend on a network of over three million miles of pipeline infrastructure. -

Classical Mechanics

Classical Mechanics Hyoungsoon Choi Spring, 2014 Contents 1 Introduction4 1.1 Kinematics and Kinetics . .5 1.2 Kinematics: Watching Wallace and Gromit ............6 1.3 Inertia and Inertial Frame . .8 2 Newton's Laws of Motion 10 2.1 The First Law: The Law of Inertia . 10 2.2 The Second Law: The Equation of Motion . 11 2.3 The Third Law: The Law of Action and Reaction . 12 3 Laws of Conservation 14 3.1 Conservation of Momentum . 14 3.2 Conservation of Angular Momentum . 15 3.3 Conservation of Energy . 17 3.3.1 Kinetic energy . 17 3.3.2 Potential energy . 18 3.3.3 Mechanical energy conservation . 19 4 Solving Equation of Motions 20 4.1 Force-Free Motion . 21 4.2 Constant Force Motion . 22 4.2.1 Constant force motion in one dimension . 22 4.2.2 Constant force motion in two dimensions . 23 4.3 Varying Force Motion . 25 4.3.1 Drag force . 25 4.3.2 Harmonic oscillator . 29 5 Lagrangian Mechanics 30 5.1 Configuration Space . 30 5.2 Lagrangian Equations of Motion . 32 5.3 Generalized Coordinates . 34 5.4 Lagrangian Mechanics . 36 5.5 D'Alembert's Principle . 37 5.6 Conjugate Variables . 39 1 CONTENTS 2 6 Hamiltonian Mechanics 40 6.1 Legendre Transformation: From Lagrangian to Hamiltonian . 40 6.2 Hamilton's Equations . 41 6.3 Configuration Space and Phase Space . 43 6.4 Hamiltonian and Energy . 45 7 Central Force Motion 47 7.1 Conservation Laws in Central Force Field . 47 7.2 The Path Equation . -

Project Final Report

Project Final Report Grant Agreement Number: FP7 - 285098 Project acronym: SOLAR-JET Project title: Solar chemical demonstration and Optimization for Long-term Availability of Renewable JET fuel Funding Scheme: Collaborative Project (Small or medium-scale focused research project) Name, title and organisation of the scientific representative of the project's coordinator: Dr Andreas Sizmann, Bauhaus Luftfahrt e.V.(BHL), Willy-Messerschmitt-Straße 1, 85521 Ottobrun, Germany Tel: +49 89 307 4849-38 Fax: +49 89 307 4849-20 E-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Final Publishable Summary Report ................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................6 1.2 Context and Objectives .............................................................................................................7 1.3 Main Results / Foreground .................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Potential Impact ..................................................................................................................... 34 1.5 SOLAR-JET Consortium ........................................................................................................ 39 2. Bibliography ...................................................................................................................................... -

Aspects of Advanced Fuel FRC Fusion Reactors

Aspects of Advanced Fuel FRC Fusion Reactors John F Santarius and Gerald L Kulcinski Fusion Technology Institute Engineering Physics Department CT2016 Irvine, California August 22-24, 2016 [email protected]; 608-692-4128 Laundry List of Fusion Reactor Development Issues • Plasma physics of fusion fuel cycles • Engineering issues unique or more ! Cross sections and Maxwellian reactivity important for DT fuel ! Beta and B-field utilization ! Tritium-breeding blanket design ! Plasma fusion power density ! Neutron damage to materials ! Plasma energy and particle confinement ! Radiological hazard (afterheat and waste disposal) ! Neutron production vs Ti for various fuel ion ratios • Safety • Geometry implications for engineering design • Environment ! Power flows • Licensing ! Direct energy conversion ! Magnet configuration • Economics ! Radiation shielding ! Maintenance in a highly radioactive environment • Nuclear non-proliferation ! Coolant piping accessibility • Non‑electric applications • Plasma‑surface interactions • 3He fuel supply JFS 2016 Fusion Technology Institute, University of Wisconsin 2 UW Developed and/or Participated in 40 MFE & 26 IFE Power Plant and Test Facility Studies in Past 46 years MFE-40 IFE-26 JFS 2016 Fusion Technology Institute, University of Wisconsin 3 Total Fusion Reactivities for Key Fusion Fuels Total Energy Production Rate st 1 generation fuels: MaxwellianTotal Reactivities -19 D + T → n (14.07 MeV) + 4He (3.52 MeV) 10 D + D → n (2.45 MeV) + 3He (0.82 MeV) → p (3.02 MeV) + T (1.01 MeV) -20 {50% each -

A Review of Energy Storage Technologies' Application

sustainability Review A Review of Energy Storage Technologies’ Application Potentials in Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration Henok Ayele Behabtu 1,2,* , Maarten Messagie 1, Thierry Coosemans 1, Maitane Berecibar 1, Kinde Anlay Fante 2 , Abraham Alem Kebede 1,2 and Joeri Van Mierlo 1 1 Mobility, Logistics, and Automotive Technology Research Centre, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.A.K.); [email protected] (J.V.M.) 2 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Jimma Institute of Technology, Jimma University, Jimma P.O. Box 378, Ethiopia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-485659951 or +251-926434658 Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 11 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Renewable energy sources (RESs) such as wind and solar are frequently hit by fluctuations due to, for example, insufficient wind or sunshine. Energy storage technologies (ESTs) mitigate the problem by storing excess energy generated and then making it accessible on demand. While there are various EST studies, the literature remains isolated and dated. The comparison of the characteristics of ESTs and their potential applications is also short. This paper fills this gap. Using selected criteria, it identifies key ESTs and provides an updated review of the literature on ESTs and their application potential to the renewable energy sector. The critical review shows a high potential application for Li-ion batteries and most fit to mitigate the fluctuation of RESs in utility grid integration sector. -

Nuclear Fusion

Copyright © 2016 by Gerald Black. Published by The Mars Society with permission NUCLEAR FUSION: THE SOLUTION TO THE ENERGY PROBLEM AND TO ADVANCED SPACE PROPULSION Gerald Black Aerospace Engineer (retired, 40+ year career); email: [email protected] Currently Chair of the Ohio Chapter of the Mars Society Presented at Mars Society Annual Convention, Washington DC, September 22, 2016 ABSTRACT Nuclear fusion has long been viewed as a potential solution to the world’s energy needs. However, the government sponsored megaprojects have been floundering. The two multi-billion- dollar flagship programs, the International Tokamak Experimental Reactor (ITER) and the National Ignition Facility (NIF), have both experienced years of delays and a several-fold increase in costs. The ITER tokamak design is so large and complex that, even if this approach succeeds, there is doubt that it would be economical. After years of testing at full power, the NIF facility is still far short of achieving its goal of fusion ignition. But hope is not lost. Several private companies have come up with smaller and simpler approaches that show promise. This talk highlights the progress made by one such private company, namely LPPFusion (formerly called Lawrenceville Plasma Physics). LPPFusion is developing focus fusion technology based on the dense plasma focus device and hydrogen-boron 11 fuel. This approach, if it works, would produce a fusion power generator small enough to fit in a truck. This device would produce no radioactivity, there would be no possibility of a meltdown or other safety issues, and it would be more economical than any other source of electricity. -

Fuel Properties Comparison

Alternative Fuels Data Center Fuel Properties Comparison Compressed Liquefied Low Sulfur Gasoline/E10 Biodiesel Propane (LPG) Natural Gas Natural Gas Ethanol/E100 Methanol Hydrogen Electricity Diesel (CNG) (LNG) Chemical C4 to C12 and C8 to C25 Methyl esters of C3H8 (majority) CH4 (majority), CH4 same as CNG CH3CH2OH CH3OH H2 N/A Structure [1] Ethanol ≤ to C12 to C22 fatty acids and C4H10 C2H6 and inert with inert gasses 10% (minority) gases <0.5% (a) Fuel Material Crude Oil Crude Oil Fats and oils from A by-product of Underground Underground Corn, grains, or Natural gas, coal, Natural gas, Natural gas, coal, (feedstocks) sources such as petroleum reserves and reserves and agricultural waste or woody biomass methanol, and nuclear, wind, soybeans, waste refining or renewable renewable (cellulose) electrolysis of hydro, solar, and cooking oil, animal natural gas biogas biogas water small percentages fats, and rapeseed processing of geothermal and biomass Gasoline or 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 1.12 B100 1 gal = 0.74 GGE 1 lb. = 0.18 GGE 1 lb. = 0.19 GGE 1 gal = 0.67 GGE 1 gal = 0.50 GGE 1 lb. = 0.45 1 kWh = 0.030 Diesel Gallon GGE GGE 1 gal = 1.05 GGE 1 gal = 0.66 DGE 1 lb. = 0.16 DGE 1 lb. = 0.17 DGE 1 gal = 0.59 DGE 1 gal = 0.45 DGE GGE GGE Equivalent 1 gal = 0.88 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 0.93 DGE 1 lb. = 0.40 1 kWh = 0.027 (GGE or DGE) DGE DGE B20 DGE DGE 1 gal = 1.11 GGE 1 kg = 1 GGE 1 gal = 0.99 DGE 1 kg = 0.9 DGE Energy 1 gallon of 1 gallon of 1 gallon of B100 1 gallon of 5.66 lb., or 5.37 lb. -

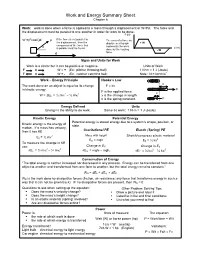

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Digital Physics: Science, Technology and Applications

Prof. Kim Molvig April 20, 2006: 22.012 Fusion Seminar (MIT) DDD-T--TT FusionFusion D +T → α + n +17.6 MeV 3.5MeV 14.1MeV • What is GOOD about this reaction? – Highest specific energy of ALL nuclear reactions – Lowest temperature for sizeable reaction rate • What is BAD about this reaction? – NEUTRONS => activation of confining vessel and resultant radioactivity – Neutron energy must be thermally converted (inefficiently) to electricity – Deuterium must be separated from seawater – Tritium must be bred April 20, 2006: 22.012 Fusion Seminar (MIT) ConsiderConsider AnotherAnother NuclearNuclear ReactionReaction p+11B → 3α + 8.7 MeV • What is GOOD about this reaction? – Aneutronic (No neutrons => no radioactivity!) – Direct electrical conversion of output energy (reactants all charged particles) – Fuels ubiquitous in nature • What is BAD about this reaction? – High Temperatures required (why?) – Difficulty of confinement (technology immature relative to Tokamaks) April 20, 2006: 22.012 Fusion Seminar (MIT) DTDT FusionFusion –– VisualVisualVisual PicturePicture Figure by MIT OCW. April 20, 2006: 22.012 Fusion Seminar (MIT) EnergeticsEnergetics ofofof FusionFusion e2 V ≅ ≅ 400 KeV Coul R + R V D T QM “tunneling” required . Ekin r Empirical fit to data 2 −VNuc ≅ −50 MeV −2 A1 = 45.95, A2 = 50200, A3 =1.368×10 , A4 =1.076, A5 = 409 Coefficients for DT (E in KeV, σ in barns) April 20, 2006: 22.012 Fusion Seminar (MIT) TunnelingTunneling FusionFusion CrossCross SectionSection andand ReactivityReactivity Gamow factor . Compare to DT . April 20, 2006: 22.012 Fusion Seminar (MIT) ReactivityReactivity forfor DTDT FuelFuel 8 ] 6 c e s / 3 m c 6 1 - 0 4 1 x [ ) ν σ ( 2 0 0 50 100 150 200 T1 (KeV) April 20, 2006: 22.012 Fusion Seminar (MIT) Figure by MIT OCW. -

Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens

Downloaded from Microscopy Pioneers https://www.cambridge.org/core Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens Eric Clark From the website Molecular Expressions created by the late Michael Davidson and now maintained by Eric Clark, National Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 . IP address: [email protected] 170.106.33.22 Christiaan Huygens reliability and accuracy. The first watch using this principle (1629–1695) was finished in 1675, whereupon it was promptly presented , on Christiaan Huygens was a to his sponsor, King Louis XIV. 29 Sep 2021 at 16:11:10 brilliant Dutch mathematician, In 1681, Huygens returned to Holland where he began physicist, and astronomer who lived to construct optical lenses with extremely large focal lengths, during the seventeenth century, a which were eventually presented to the Royal Society of period sometimes referred to as the London, where they remain today. Continuing along this line Scientific Revolution. Huygens, a of work, Huygens perfected his skills in lens grinding and highly gifted theoretical and experi- subsequently invented the achromatic eyepiece that bears his , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at mental scientist, is best known name and is still in widespread use today. for his work on the theories of Huygens left Holland in 1689, and ventured to London centrifugal force, the wave theory of where he became acquainted with Sir Isaac Newton and began light, and the pendulum clock. to study Newton’s theories on classical physics. Although it At an early age, Huygens began seems Huygens was duly impressed with Newton’s work, he work in advanced mathematics was still very skeptical about any theory that did not explain by attempting to disprove several theories established by gravitation by mechanical means. -

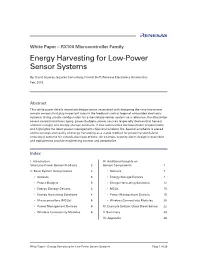

Energy Harvesting for Low-Power Sensor Systems

White Paper – RX100 Microcontroller Family Energy Harvesting for Low-Power Sensor Systems By: David Squires, Squires Consulting; Forrest Huff, Renesas Electronics America Inc. Feb. 2015 Abstract This white paper details important design issues associated with designing the very-low-power remote sensors that play important roles in the feedback control loops of embedded electronic systems. Using a basic configuration for a standalone sensor system as a reference, the discussion covers sensor/transducer types, power budgets, power sources (especially devices that harvest ambient energy) and energy-storage solutions. It also summarizes microcontroller requirements and highlights the latest power-management chips and wireless ICs. Special emphasis is placed on the concept and reality of energy harvesting as a viable method for powering standalone embedded systems for extended periods of time. An example security alarm design is described and explained to provide engineering context and perspective. Index I. Introduction – III. Additional Insights on Very-Low-Power Sensor Products 2 Sensor Components 7 II. Basic System Design Issues 2 • Sensors 7 • Sensors 3 • Energy Storage Devices 7 • Power Budgets 3 • Energy Harvesting Solutions 12 • Energy Storage Devices 3 • MCUs 15 • Energy Harvesting Solutions 4 • Power Management Devices 18 • Microcontrollers (MCUs) 6 • Wireless Connectivity Modules 20 • Power Management Devices 6 IV. Example Design: Glass Break Sensor 22 • Wireless Connectivity Modules 6 V. Summary 28 VI. Appendix 28 White Paper – Energy Harvesting for Low-Power Sensor Systems Page 1 of 29 I. Introduction – Very-Low-Power Sensor Products Modern low-power sensors enable precise local, remote or autonomous control of a vast range of products. Their use is rapidly proliferating in vehicles, appliances, HVAC systems, hospital intensive care suites, oil refineries, and military and security systems. -

Taylor Farms Achieves Industry First Sustainability Milestones in Energy Independence and Waste Conservation

Taylor Farms Achieves Industry First Sustainability Milestones in Energy Independence and Waste Conservation January 14th, 2020 Three facilities are now Total Resource Use and Efficiency (TRUE) platinum zero waste certified and more than 90 percent energy independent SALINAS, Calif. – Jan. 13, 2020 –Taylor Farms, North America’s leading producer of salads and healthy fresh foods, has received the U.S. Green Building Council TRUE platinum zero waste certification at three facilities in California while simultaneously achieving 90 percent energy independence from the utility grid through unique microgrid solutions. Together, their unique suite of investments and programs reduced 175,000 metric ton (MT) of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in just two years, equivalent to 37,000 cars off the road annually. The three facilities in Monterey County are the first fresh food facilities to achieve the highest level of TRUE zero waste certification, diverting over 95 percent of materials from the environment, incinerators and landfills. “Now more than ever before, we are noticing a shift in customers, consumers and business partners to be increasingly more aware of the source of their food and the sustainable practices behind that food production,” said Bruce Taylor, Chairman and CEO, Taylor Farms. “We are proud that Taylor Farms is at the forefront of developing and identifying sustainability practices that are breaking down barriers and establishing new norms within the industry. Consumers should be confident that our product offerings are helping them to lead healthy lives while contributing to a healthy environment and healthy communities.” “We commend Taylor Farms for their leadership and climate action achievements, which have made a positive impact in our shared sustainability journey.” Townsend Bailey, Director - North America Sustainability, McDonald’s Building an industry first groundbreaking microgrid and Environmental Management System (EMS) takes entrepreneurial drive and strategic partnerships.