The Gunpowder Plot House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bonfire Night

Bonfire Night What Is Bonfire Night? Bonfire Night remembers the failed attempt to kill the King of England and the important people of England as they gathered for the State Opening of Parliament on 5th November 1605. Bonfires were lit that first night in a joyful celebration of the King being saved. As the years went by, the burning of straw dummies representing Guy Fawkes was a reminder that traitors would never successfully overthrow a king. The Gunpowder Plot After Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, the English Catholics were led to believe that the Act of terrorism: new King, James I, would be more accepting Deliberate attempt to kill of them. However, he was no more welcoming or injure many innocent of Catholic people than the previous ruler people for religious or which led some people to wish he was off the political gain. throne to allow a Catholic to rule the country. A small group of Catholic men met to discuss what could be done and their leader, Robert Catesby, was keen to take violent action. Their plan was to blow up the Houses of Parliament, killing many important people who they did not agree with. This was an act of terrorism. They planned to kill all of the leaders who were making life difficult for the Catholic people. They recruited a further eight men to help with the plot but as it took form, some of the group realised that many innocent people would be killed, including some who supported the Catholic people. This led some of the men to begin to have doubts about the whole plot. -

The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack

TTHHEE GGUUNNPPOOWWDDEERR PPLLOOTT The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack Welcome to Heritage Doncaster’s the Gunpowder Plot activity pack. This booklet is filled with ideas that you can have a go at as a family at home whilst learning about the Gunpowder Plot. Some of these activities will require adult supervision as they require using an oven, a sharp implement, or could just be a bit tricky these have been marked with this warning triangle. We would love to see what you create so why not share your photos with us on social media or email You can find us at @doncastermuseum @DoncasterMuseum [email protected] Have Fun! Heritage Doncaster Education Service Contents What was the Gunpower Plot? Page 3 The Plotters Page 4 Plotters Top Trumps Page 5-6 Remember, remember Page 7 Acrostic poem Page 8 Tunnels Page 9 Build a tunnel Page 10 Mysterious letter Page 11 Letter writing Page 12 Escape and capture Page 13 Wanted! Page 14 Create a boardgame Page 15 Guy Fawkes Night Page 16 Firework art Page 17-18 Rocket experiment Page 19 Penny for a Guy Page 20 Sew your own Guy Page 21 Traditional Bonfire Night food Page 22 Chocolate covered apples Page 23 Wordsearch Page 24 What was the Gunpowder Plot? The Gunpowder Plot was a plan made by thirteen men to blow up the Houses of Parliament when King James I was inside. The Houses of Parliament is an important building in London where the government meet. It is made up of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. -

Tudors and the Reformation

Knowledge Organiser: Tudors and the Reformation The Catholic Church faced criticism in the Chronology: what happened on these dates? Vocabulary: define these words 16th century, leading to the Reformation. Martin Luther pins his ‘95 theses’ to the A promise to reduce time spent Some rulers left it and set up their own 1517 Indulgence churches, causing plots, revolts and wars. church door in Wittenberg. in purgatory. Summarise your learning Henry VIII declares himself head of the A movement that divided the 1534 Reformation Church of England. Christian Church in Europe. Criticisms The quality and practices of the of the Church were criticised by Martin The process of dissolving England’s A person that disagrees with the Catholic 1536 Heretic Luther. monasteries begins. official Church. Church Edward VI becomes king and begins to A group of Christians, who broke 1547 Protestant accelerate the Reformation in England. away from the Catholic Church. The Reformation spread across The belief that Jesus Christ is The Mary I becomes queen and tries to reverse Europe, weakening the position 1553 Transubstantiation physically present in the bread Reformation the Reformation in England. of the Catholic Church. and wine during mass. Elizabeth I succeeds Mary and sets up her Declaration that a marriage is 1559 Annulment Henry’s Henry VIII wanted a divorce and own Religious Settlement. invalid. ‘Great had to break from Rome to get Who were these people? What were these events? Matter’ one. The closure and sale of A former monk, who started the Protestant Dissolution Martin Luther England’s monasteries. Reformation in Europe. Impact of In England, the monasteries were Mary, Queen of A rival to the English throne, who fled there the dissolved and the Church Scots after her nobles revolted. -

“Gunpowder Empires” of the Islamic World During the Early Modern Era (1450-1750)! India 3 Continents: SE Europe, N

Let’s review the three “Gunpowder Empires” of the Islamic World during the Early Modern Era (1450-1750)! India 3 continents: SE Europe, N. Africa, SW Asia Persia (Iran today) Longest lasting- existed until the end of World War I Ended when Europeans (specifically the British) gained control Had a powerful army with artillery (muskets and cannons) Defeated the Safavids at the Battle of Chaldiran- set the Iran/Iraq boundary today Established by Turkish Muslim warriors Claimed descent from Mongols Ruled over a largely Hindu population Ruled over a diverse population with many Christians and Jews Leader called a sultan Leader called a shah Had emperors Religiously tolerant New syncretic belief: Sikhism Shi’a Sunni Defeated the Byzantine Empire- seized Constantinople The Persian spoken began to incorporate Arabic words Followed after the Delhi Sultanate Answer Key OTTOMAN EMPIRE SAFAVID EMPIRE MUGHAL EMPIRE ● 3 continents: SE Europe, N. ● Persia (Iran today) ● India Africa, SW Asia ● Had a powerful army with ● Ended when Europeans ● Longest-lasting: existed until artillery (muskets and cannons) (specifically the British) gained the end of World War I ● Leader called a shah control of India ● Had a powerful army with ● Religiously tolerant ● Had a powerful army with artillery (muskets and cannons) ● Shi’a artillery (muskets and cannons) ● Defeated Safavids at the Battle ● The Persian spoken began to ● Established by people of Chaldiran- set the Iran/Iraq incorporate Arabic words descended from Turkish Muslim boundary today warriors ● Established -

Tinker Emporium Tinker Emporium Vol. Firearms Vol. 7

Tinker Emporium Vol. 7 Firearms Introduction : This file contains ten homebrew firearms (based on real world) , each presented with a unique description and a colored picture. Separate pictures in better resolution are included in the download for sake of creating handouts, etc. by Revlis M. Template Created by William Tian DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D& D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Co ast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any re production or unauthorized use of the mater ial or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2018 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057 -0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 SampleThe Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, file Not for resale. Permission granted to print or photocopy this document for personal use only . T.E. Firearms 1 Firearms Fire L ance Introduction and Points of Interest Firearm, 5 lb, Two-handed, (2d4) Bludgeoning, Ranged (15/30), Reload, Blaze Rod What are Firearms in D&D Firearms by definition are barreled ranged weapons that inflict damage by launching projectiles. In the world of D&D the firearms are created with the use of rare metals and alchemical discoveries. -

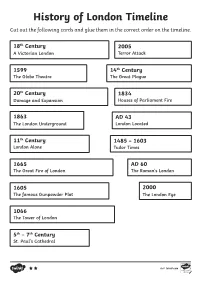

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

Modern Guns and Smokeless Powder

BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Henrg W. Sage 1S91 /\:,JM^n? ^I'tClfl ofseo Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030760072 : : MODERN GUNS AND SMOKELESS POWDER. ARTHUR RIGG JAMES GARVIE. LONDON E. & F. N. SPON, 125, STRAND. NEW YORK SPON & CHAMBERLAIN, 12, CORTLANDT STREET. 1892. MODERN GUNS AND SMOKELESS POWDER. PART I. INTRODUCTION. Gunpowder, the oldest of all explosives, has been the subject of many scientific investigations, sup- ported by innumerable experiments ; but Nature guards her secrets well ; and to this day it cannot be said that the cycle of chemical changes brought about by the combustion of gunpowder is thoroughly understood. Its original components vary, but are generally about 75 parts potassium nitrate, 15 parts carbon, and 10 parts sulphur, with other ingredients some- times added. These materials, when simply mixed together, burn with considerable vigour, but cannot rank as an explosive until they have been thoroughly incorporated, so that the different molecules are brought into such close proximity that each finds a neighbour ready and willing to combine on the smallest encouragement. Heat furnishes the necessary stimulus, by pro- 2 MODERN GUNS AND SMOKELESS POWDER. moting chemical activity ; and, when combined with concussion, the molecules are driven closer to- gether, and this intimate association accelerates their combination. The effect of mere concussion is shown to greater advantage when any of the more dangerous ex- plosives, such as iodide of nitrogen, are subjected to experiment. -

British Festivals: Guy Fawkes, Bonfire Night

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PublicacionesDidácticas (E-Journal) British festivals: Guy Fawkes, Bonfire Night Autor: Martínez García, María Rosario (Maestra de Lenguas Extranjeras (Inglés), Maestra de Inglés en Educación Primaria). Público: Maestros o profesores de lengua inglesa de cualquier etapa educativa. Materia: Inglés. Idioma: Inglés. Title: British festivals: Guy Fawkes, Bonfire Night. Abstract The powerpoint explained next is about the festivity of "Guy Fawkes", or also known as "Bonfire Night". Through different images the story is told and the meaning of why it is celebrated is explained, not very known in Spain. Information is given about how it is celebrated in the United Kingdom and the different activities children carry out there. A rhyme will be taught and finally evaluation activities are given. Keywords: british culture, guy fawkes, bonfire night. Título: Festifvidades Británicas: Guy Fawkes. Resumen El PowerPoint explicado a continuación trata sobre la festividad de "Guy Fawkes", o también llamada "la noche de la hoguera". A través de imágenes se cuenta la historia y el significado de por qué se celebra esta festividad, en España poco conocida. Se da información de cómo se celebra en el Reino Unido y las distintas actividades que realizan los niños allí. Se les enseña una rima y finalmente se dan actividades de evaluación oral. Palabras clave: Cultura inglesa, actividades, noche de la hoguera. Recibido 2016-01-21; Aceptado 2016-01-25; Publicado 2016-02-25; Código PD: 068075 British culture is one of the most important aspects to treat in our English classroom. -

History of the Gunpowder Plot & Guy Fawkes Night Four Hundred Years Ago, in 1605, a Man Called Guy Fawkes and a Group Of

History of the Gunpowder Plot & Guy Fawkes Night Four hundred years ago, in 1605, a man called Guy Fawkes and a group of plotters attempted to blow up the Houses of Parliament in London with barrels of gunpowder placed in the basement. They wanted to kill King James and the king’s leaders. Houses of Parliament, London Why did Guy Fawkes want to kill King James 1st and the king’s leaders? When Queen Elizabeth 1st took the throne of England she made some laws against the Roman Catholics. Guy Fawkes was one of a small group of Catholics who felt that the government was treating Roman Catholics unfairly. They hoped that King James 1st would change the laws, but he didn't. Catholics had to practise their religion in secret. There were even fines for people who didn't attend the Protestant church on Sunday or on holy days. James lst passed more laws against the Catholics when he became king. What happened - the Gunpowder Plot A group of men led by Robert Catesby, plotted to kill King James and blow up the Houses of Parliament, the place where the laws that governed England were made. Guy Fawkes was one of a group of men The plot was simple - the next time Parliament was opened by King James l, they would blow up everyone there with gunpowder. The men bought a house next door to the parliament building. The house had a cellar which went under the parliament building. They planned to put gunpowder under the house and blow up parliament and the king. -

The Ottoman Gunpowder Empire and the Composite Bow Nathan Lanan Gettysburg College Class of 2012

Volume 9 Article 4 2010 The Ottoman Gunpowder Empire and the Composite Bow Nathan Lanan Gettysburg College Class of 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Military History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Lanan, Nathan (2010) "The Ottoman Gunpowder Empire and the Composite Bow," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 9 , Article 4. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol9/iss1/4 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ottoman Gunpowder Empire and the Composite Bow Abstract The Ottoman Empire is known today as a major Gunpowder Empire, famous for its prevalent use of this staple of modern warfare as early as the sixteenth century. However, when Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq visited Constantinople from 1554 to 1562, gunpowder was not used by the Sipahi cavalry who stubbornly, it seems, insisted on continuing to use the composite bow that the Turks had been using for centuries. This continued, despite their fear of European cavalry who used “small muskets” against them on raids. Was this a good idea? Was the composite bow a match or contemporary handheld firearms? Were Turkish tactics incompatible with firearms to the point that the Ottomans would have lost their effectiveness on the battlefield? Could the -

Guided Cycle Ride

Cyclesolihull Routes Cyclesolihull Rides short route from Cycling is a great way to keep fit whilst at Cyclesolihull offers regular opportunities to S1 the same time getting from A to B or join with others to ride many of the routes in Dorridge exploring your local area. this series of leaflets. The rides are organised This series of routes, developed by by volunteers and typically attract between 10 and 20 riders. To get involved, just turn up and Cyclesolihull will take you along most of ride! the network of quiet lanes, roads and cycle paths in and around Solihull, introducing Sunday Cycle Rides take place most Cyclesolihull Sunday afternoons at 2 pm from April to you to some places you probably didn’t Explore your borough by bike even know existed! September and at 1.30 pm from October to March. One of the routes will be followed with a The routes have been carefully chosen to mixture of route lengths being ridden during avoid busier roads so are ideal for new each month. In autumn and winter there are cyclists and children learning to cycle on more shorter rides to reflect the reduced daylight hours. One Sunday each month in the road with their parents. spring and summer the ride is a 5 mile Taster You can cycle the routes alone, with family Ride. This is an opportunity to try a and friends, or join other people on one of Cyclesolihull ride without going very far and is the regular Cyclesolihull rides. an ideal introduction to the rides, especially for new cyclists and children. -

Prices of Weapons and Munitions in Early Sixteenth Century Holland During the Guelders War1

James P. Ward Prices of Weapons and Munitions in Early Sixteenth Century Holland during the Guelders War1 1. Introduction The adage that to have peace one has to prepare for war may not be of Classical antiquity but the principle was known to Livy and the Ancients,2 and so the influence of the weapons industry on world peace and economy hardly needs to be emphasized now. The purpose of this article is both to present data on retail prices of individual weapons and munitions of war in the first decades of the sixteenth century in Holland, and to show how the magistrates there prepared to defend their cities against an aggressor by purchasing weapons to arm the citizens. Prices quoted here for strategic commodities of war in the early sixteenth century complement those given by Posthumus in his survey of prices for the later sixteenth century and beyond.3 Kuypers published inventories of weapons maintained in castles and elsewhere in Holland and the Netherlands in the first half of the sixteenth century, but the cities of Holland were not included in his descriptions.4 A recent study by De Jong reveals the growth of the early modern weapons industry in the Republic of the United Netherlands in the period 1585-1621 as part of a process of state formation based on entrepreneurship, economic growth and military reform.5 As sources for the present investigation accounts of the Treasurer for North-Holland at The Hague, and of the city treasurers of Haarlem, Leiden, Dordrecht and Gouda were examined for expenditures on weapons and munitions.