Counterterrorism: Punjab a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shri Bakhshish Singh S/O Sh. Labh Singh, Village: Lodhipur, PO: Khunda, Tehsil & District: Gurdaspur. …Appellant Versus

PUNJAB STATE INFORMATION COMMISSION RED CROSS BUILDING, SECTOR-16, MADHYA MARG, CHANDIGARH Tele No. 0172-2864118, FAX No. 0172-2864125, Visit us @ www.infocommpunjab.com Email:[email protected] Shri Bakhshish Singh s/o Sh. Labh Singh, Village: Lodhipur, PO: Khunda, Tehsil & District: Gurdaspur. …Appellant Versus Public Information Officer O/O Block Development & Panchayat Officer, Gurdaspur. First Appellate Authority, O/O District Development & Panchayat Officer, Gurdaspur. ….. Respondents APPEAL CASE NO. 228 of 2019 Present: None on behalf of appellant. Shri Amarpal Singh, Panchayat Secretary, on behalf of respondents. ORDER: The representative of respondents brings information with him to supply the same to the appellant in the court. 2. The appellant is not present in the court. 3. The respondents are directed to send the information to the appellant by registered post before the next date of hearing. 4. The appellant is directed to point out deficiencies, if any, to the respondents on receipt of information and also to be present in the court on the next date of hearing. Adjourned. 5. To come up for further hearing on 04-06-2019 at 11.30 AM. 6. Copy of order be sent to the parties. Sd/- Place : Chandigarh. ( Hem Inder Singh ) Dated: 11-04-2019. State Information Commissioner PUNJAB STATE INFORMATION COMMISSION RED CROSS BUILDING, SECTOR-16, MADHYA MARG, CHANDIGARH Tele No. 0172-2864118, FAX No. 0172-2864125, Visit us @ www.infocommpunjab.com Email:[email protected] Shri Harnek Singh Bhari, House No. HE-155, Phase-1, SAS Nagar (Mohali). …Complainant Versus Public Information Officer O/O Financial Commissioner, Rural Development & Panchayats, Punjab, Vikas Bhawan, Sectort 68, Mohali. -

Nishaan – Blue Star-II-2018

II/2018 NAGAARA Recalling Operation ‘Bluestar’ of 1984 Who, What, How and Why The Dramatis Personae “A scar too deep” “De-classify” ! The Fifth Annual Conference on the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, jointly hosted by the Chardi Kalaa Foundation and the San Jose Gurdwara, took place on 19 August 2017 at San Jose in California, USA. One of the largest and arguably most beautiful gurdwaras in North America, the Gurdwara Sahib at San Jose was founded in San Jose, California, USA in 1985 by members of the then-rapidly growing Sikh community in the Santa Clara Valley Back Cover ContentsIssue II/2018 C Travails of Operation Bluestar for the 46 Editorial Sikh Soldier 2 HERE WE GO AGAIN: 34 Years after Operation Bluestar Lt Gen RS Sujlana Dr IJ Singh 49 Bluestar over Patiala 4 Khushwant Singh on Operation Bluestar Mallika Kaur “A Scar too deep” 22 Book Review 1984: Who, What, How and Why Jagmohan Singh 52 Recalling the attack on Muktsar Gurdwara Col (Dr) Dalvinder Singh Grewal 26 First Person Account KD Vasudeva recalls Operation Bluestar 55 “De-classify !” Knowing the extent of UK’s involvement in planning ‘Bluestar’ 58 Reformation of Sikh institutions? PPS Gill 9 Bluestar: the third ghallughara Pritam Singh 61 Closure ! The pain and politics of Bluestar 12 “Punjab was scorched 34 summers Jagtar Singh ago and… the burn still hurts” 34 Hamid Hussain, writes on Operation Bluestar 63 Resolution by The Sikh Forum Kanwar Sandhu and The Dramatis Personae Editorial Director Editorial Office II/2018 Dr IJ Singh D-43, Sujan Singh Park New Delhi 110 -

The Causes and Consequences of State Repression in Internal Armed Conflict: Sub-State Capacity and the Targets of State Violence

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Political Science ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-5-2013 The aC uses and Consequences of State Repression in Internal Armed Conflict: Sub-State Capacity and the Targets of State Violence Philip Hultquist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/pols_etds Recommended Citation Hultquist, Philip. "The aC uses and Consequences of State Repression in Internal Armed Conflict: Sub-State Capacity and the Targets of State Violence." (2013). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/pols_etds/10 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Philip Hultquist Candidate Political Science Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Christopher K. Butler, Chairperson William Stanley Mark Peceny Neil Mitchell i THE CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF STATE REPRESSION IN INTERNAL ARMED CONFLICT: SUB-STATE CAPACITY AND THE TARGETS OF STATE VIOLENCE by PHILIP HULTQUIST B.S., Government and Public Affairs, Missouri Western State University, 2004 M.A., Political Science, University of New Mexico, 2007 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2013 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who has supported me while completing my doctoral degree and especially while writing this dissertation. To do so, however, would result in an acknowledgements section much longer than the dissertation. -

Circular Regarding Recruitment of Registrar in Armed Forces Tribunal

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF DEFENCE ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, PRINCIPAL BENCH West Block-VIII R.K. Puram, Sector~! New Delhi - 110 066 F. No. 7(27)/2015/AFT/PB/Adm-ll Dated : 23rd Nov 2017 CIRCULAR Applications are invited for filling up of the post of Registrar in the Armed Forces Tribunal, Regional Bench; Srinagar {temporarily to function at Jammu) on deputation basis initially for a period of one year extendable upto three years or on re-employment on contract basis for a period of one year, from sLtitable candidates who fulfill the following eligibility conditions:- Name of No. of Pay scale {Rs.) Eligibility conditions the Post ! Post ! I For Deputation: Registrar 01 New pay scale pay j matrix civilian 1 Officers of Central Government or State I employees level-131! Government or Supreme Court or High Courts or I (General or equivalent pay District Court or Statutory/Autonomous bodies I Central level 1 having pensionary benefits or Judge Advocate ! Service (Pay Band- 4) ! General Branch of Army, Navy & Air Force and 1 Group 'A' I Rs.37400- 67000 ! other similar institutions. Gazetted, +Grade Pay l Non~ Rs .. 8700/- (pre- 1 (a) (i) holding analogous post on regular Ministerial ) revised) basts, in the parent cadre or Department. 1 (ii) five years regular service in the parent Cadre or Department in the Level-12 as per I the th CPC Pay Matrix or equivalent in Pay Band-3 of Rs. 15600-39100 with I Grade pay Rs. 7600 (pre- revised). (b) holding degree in law from a recognised I University with five years regular service. -

Ex Havildar and Hony Nb Sub Desh Raj Yadav, Resident of Village & PO Saga, Tehsil Buhana, District Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, JAIPUR APPLICANT : Ex Havildar and Hony Nb Sub Desh Raj Yadav, Resident of Village & PO Saga, Tehsil Buhana, District Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan VERSUS NON - APPLICANTS 1. Union of India through the Secretary, Ministry of Defence, South Block, New Delhi – 110 011 2. Principal Controller of Defence Accounts (Pension), Draupadi Ghat, Allahabad – 211 014 (UP) 3. The OIC Records, The Kumaon Records, Ranikhet – 263 645 ORIGINAL APPLICATION NO 05 OF 2017 Under Section 14 of the Armed Forces Tribunal Act, 2007 DATE OF ORDER : 07th NOVEMBER, 2017 PRESENT HON'BLE MR JUSTICE BABU MATHEW P. JOSEPH, MEMBER (J) HON'BLE VICE ADMIRAL MP MURALIDHARAN, MEMBER (A) Shri Yogendra Singh, counsel for the applicant Shri Arun Kumar, counsel for the respondents Maj Manisha Yadav, OIC Legal Cell for respondents 2 ORDER JUSTICE BABU MATHEW P. JOSEPH, MEMBER (J) 1. This Original Application has been filed claiming pension as applicable to Honorary Naib Subedar with effect from 01/1/2006. 2. Heard Shri Yogendra Singh, learned counsel appearing for the applicant, and Shri Arun Kumar, learned Central Government Counsel appearing for the respondents. 3. The applicant was discharged from the Indian Army on 31/1/2005 while serving as a Havildar. Subsequently, he was granted the Honorary rank of Naib Subedar on 15/8/2005. The applicant claims pension as applicable to Honorary Naib Subedar on the strength of the policy letter dated 12/6/2009 issued by the Government of India, Ministry of Defence. 4. There is no dispute with regard to the fact that the persons like the applicant are entitled to revised pension as applicable to Honorary Naib Subedar with effect from 01/1/2006 on the strength of the Orders issued by the Government of India and as held by different Benches of the Armed Forces Tribunal. -

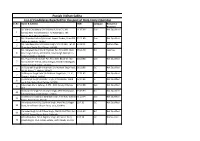

Punjab Vidhan Sabha List of Candidates Rejected for the Post of Data Entry Operator Sr.No Name & Address DOB Category Reason for Rejection Sh

Punjab Vidhan Sabha List of Candidates Rejected for the post of Data Entry Operator Sr.No Name & Address DOB Category Reason for Rejection Sh. Vishu Chaudhary S/o Dina Nath, H.no 71, Vill. 11.07.96 Gen Not Qualified* 1 Kansal, Near Krishan Mandir, PO Naya Gaon, Teh. Kharar, Distt Mohali.160103 Ms. Priyanka Sachar D/o Ashok Kumar Sachar, H.no 458, 05.11.88 Gen Not Qualified 2 Sector 65 Mohali. 160062 Ms. Mandeep Kaur D/o Kesar Singh, VPO Chakla, Teh Sh 29.08.91 B.C Without fee 3 Chamkaur Sahib, Distt Ropar. 140102 Ms. Gurpreet Kaur S/o Sh Rajinder Pal, H.no 190, Akali 03.11.79 B.C Less Fee 4 Kaur Singh Colony, Vill Bhabat, Dault Singh Wala(A.K.S Colony) Zirakpur.140603 Ms. Pooja D/o Sh Surider Pal, H.no 359, Block -B, near 20.10.86 Gen Not Qualified 5 Sooraj Model School, Adrash Nagar, Mandi Gobindgarh, Distt Fatehgarh Sahib. 147301. Sh Gurpreet Singh@ Vinod Kalsi S/o Malkeet Singh Kalsi, 06.10.88 S.C Not Qualified 6 HL-31, Phase-7, Mohali. 160062 Sh Manjeet Singh Kalsi S/o Malkeet Singh Kalsi, HL-31, 27.01.85 S.C Not Qualified 7 Phase-7, Mohali. 160062 Sh Paramjit Singh S/o Balbir Singh, VPO Bhadso, Ward 03.04.85 S.T Not Qualified 8 no. 9, Teh Naba, Distt Patiala. 147202 S.Sandeep S/o S. Sehsraj, # 372 , Milk Colony, Dhanas, 27.12.88 Gen Not Qualified 9 Chd. Sh Gurpreet Singh S/o Gurnam Singh, VPO Bhakharpur, 05.05.93 B.C Not Qualified 10 Teh Dera Bassi, Distt Mohali. -

SIKH1SM and the NIRANKARI MOVEMENT 2-00

SIKH1SM and THE NIRANKARI MOVEMENT 2-00 -00 -00 -00 2-00 -00 00 00 00 ACADEMY OF SIKH RELIGION AND CULTURE 1, Dhillon Marg, Bhupinder Nagar PAT I ALA SIKHISM and THE NIRANKARI MOVEMENT ACADEMY OF SIKH RELIGION AND CULTURE 1. Dhillon Marg, Bhupinder Nagar PATIALA ^^^^^ Publisher's Note Nirankari movement was founded as renaissance of Sikh religion but lately an off-shoot of Nirankaris had started ridiculing Sikh Religion and misinterpreting Sikh scriptures for boosting up the image of their leader who claims to be spiritual head; God on Earth and re-incarnate of Shri Rama, Shri Krishna, Hazrat Mohammed, Holy Christ and Sikh Gurus. The followers of other religions did not react to this blasphemy. The Sikhs, however, could not tolerate the irreverance towards Sikh Gurus, Sikh religion and Sikh scrip tures and protested against it. This pseudo God resented the protest and became more vociferous in his tirade against Sikhs, their Gurus and their Scriptures. His temerity resulted in the massacre of Sikhs at Amritsar on 13th April, 1978 (Baisakhi day) at Kanpur on 26th September, 1978 and again in Delhi on 5th, November 1978. This booklet is published to apprise the public of the back ground of Nirankaris, the off-shoot of Nirankaris, the cause of controversy and the aftermath. It contains three articles : one, by Dr. Ganda Singh, a renowned historian, second, by Dr. Fauja Singh of Punjabi University, Patiala. and third, by S. Kapur Singh, formerly of I.C.S. cadre. A copy of the report of the Enquiry Committee on the Happen ings at Kanpur, appointed by the Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee whose members were S. -

Sant Sundar Singh Ji

Sant Giani Sundar Singh later successively from two Udasi understanding of Gurbani (Brahm scholars, Pandit Javala Das and Gian), within two years. Sant Sunder Singh Ji Pandit Bhagat Ram. Bhindranwaalay was a great Before Sant Bishan Singh Ji Gursikh who led an exemplary life, His father at the same time taught ascended to Sach Khand he gave did massive parchaar of Sikhi, him the banis of: Panj Granthi, Sant Giani Sundar Singh Ji the inspired countless to take amrit and Baaee Vaaraa(n), Bhagat Bani, and chance to ask for anything he taught Gurbani and Gurbani Das Granthi. Around the age of 9 or wanted, as he had spent their time meanings to countless students, in 10 he was taught how to read Sri at Murale doing selfless service. his short life of 42 years or so. Guru Granth Sahib Ji, and he Sant Giani Sundar Singh Ji replied became an Akhand Paati by the without any ego, "it is up to you to Sant Giani Sundar Singh ji was efforts of his father. It was at this decide" what you grace me with. born at amrit vela at village time he joined the Khalsa Panth by Sant Bishan Singh Ji declared that Bhindran Kalan, state Firozpur, on taking Amrit from Panj Pyare. Until he should for the rest of their life 18 August 1883. His father’s name the age of 17 years he stayed at preach the word of Guru Ji, teach was Baba Khajaan Singh and his home learning the understanding of the sangat the meanings of Gurbani mother’s name Bibi Mehtab Kaur. -

Group Housing

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- GROUP HOUSING S# RID PROPERTY NO. APPLICANT NAME AREA 1 60244956 29/1013 SEEMA KAPUR 2,000 2 60191186 25/K-056 CAPT VINOD KUMAR, SAROJ KUMAR 128 3 60232381 61/E-12/3008/RG DINESH KUMAR GARG & SEEMA GARG 154 4 60117917 21/B-036 SUDESH SINGH 200 5 60036547 25/G-033 SUBHASH CH CHOPRA & SHWETA CHOPRA 124 6 60234038 33/146/RV GEETA RANI & ASHOK KUMAR GARG 200 7 60006053 37/1608 ATEET IMPEX PVT. LTD. 55 8 39000209 93A/1473 ATS VI MADHU BALA 163 9 60233999 93A/01/1983/ATS NAMRATA KAPOOR 163 10 39000200 93A/0672/ATS ASHOK SOOD SOOD 0 11 39000208 93A/1453 /14/AT AMIT CHIBBA 163 12 39000218 93A/2174/ATS ARUN YADAV YADAV YADAV 163 13 39000229 93A/P-251/P2/AT MAMTA SAHNI 260 14 39000203 93A/0781/ATS SHASHANK SINGH SINGH 139 15 39000210 93A/1622/ATS RAJEEV KUMAR 0 16 39000220 93A/6-GF-2/ATS SUNEEL GALGOTIA GALGOTIA 228 17 60232078 93A/P-381/ATS PURNIMA GANDHI & MS SHAFALI GA 200 18 60233531 93A/001-262/ATS ATUULL METHA 260 19 39000207 93A/0984/ATS GR RAVINDRA KUMAR TYAGI 163 20 39000212 93A/1834/ATS GR VIJAY AGARWAL 0 21 39000213 93A/2012/1 ATS KUNWAR ADITYA PRAKASH SINGH 139 22 39000211 93A/1652/01/ATS J R MALHOTRA, MRS TEJI MALHOTRA, ADITYA 139 MALHOTRA 23 39000214 93A/2051/ATS SHASHI MADAN VARTI MADAN 139 24 39000202 93A/0761/ATS GR PAWAN JOSHI 139 25 39000223 93A/F-104/ATS RAJESH CHATURVEDI 113 26 60237850 93A/1952/03 RAJIV TOMAR 139 27 39000215 93A/2074 ATS UMA JAITLY 163 28 60237921 93A/722/01 DINESH JOSHI 139 29 60237832 93A/1762/01 SURESH RAINA & RUHI RAINA 139 30 39000217 93A/2152/ATS CHANDER KANTA -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR th MONDAY,THE 18 NOVEMBER, 2019 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 58 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 59 TO 64 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 65 TO 77 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 78 TO 92 REGISTRAR (APPLT.)/ REGISTRAR (LISTING)/ REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 18.11.2019 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 18.11.2019 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE C.HARI SHANKAR FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. W.P.(C) 11641/2019 DR. NAND KISHORE GARG SHASHANK DEO SUDHI CM APPL. 47830/2019 Vs. GOVT. OF NCT OF DELHI AND ANR. FOR ADMISSION _______________ 2. FAO(OS) (COMM) 278/2018 ANUP N. KOTHARI & ANR ANUSUYA SALWAN,ACHAL CM APPL. 49365/2018 Vs. ROOPAK N. KOTHARI & ANR GUPTA,GURPREET SINGH KAHLON CM APPL. 49366/2018 3. W.P.(CRL) 2075/2019 PRAMOD GOSWAMI AMIT SAHNI CRL.M.A. 32154/2019 Vs. STATE & ANR. Other Case filed against same P.S.-FIR No. :(ASHOK VIHAR-408/2008) CRL.REV.P. 385/2010 filed by PRAMOD GOSWAMI (Disposed on : 02-MAY-12 ) CRL.A. 1368/2013 filed by PRAMOD (Disposed on : 15-JAN-16 ) W.P.(CRL) 1002/2016 filed by PRAMOD (Disposed on : 19-APR-16 ) P.S.-FIR No. :(ASHOK VIHAR-408/2008) AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 4. CONT.CAS(C) 464/2018 DUGGAL COLONY RESIDENT DEVINDER CHOWDHURY,NEELAM WELFARE ASSOCIATION ( REGD) RATHORE ASSOCIATES,TUSHAR Vs. -

India: the Security Situation in Punjab, Including Patterns of Violence, The

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 23 January 2006 IND100772.E India: The security situation in Punjab, including patterns of violence, the groups involved, and the government's response (2002 - 2005) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa Overview In its 2002 assessment of Punjab state, South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) concluded that Punjab state "remains largely free from terrorist violence for the ninth consecutive year," explaining that "the ideology of [an independent state of] Khalistan has lost appeal among the people of Punjab, and even public calls to revive secession and terrorist violence have faded out" (SATP n.d.b). This general atmosphere is reflected in SATP's South Asia Conflict Maps for 2003 and 2004, which do not include Punjab state as an area of "conflict" (SATP n.d.c.; ibid. n.d.d.). Similarly, according to a 2003 article by a research associate with the Institute for Conflict Management (ICM) in New Delhi, India, which is "committed to the continuous evaluation and resolution of problems of internal security in South Asia" (ICM n.d.a), anti-Sikh violence in Punjab state had been "settled" (IPCS 24 June 2003). Les Nouveaux Mondes rebelles, on the other hand, reported in 2005 that the Punjab state independence conflict was "on its way to being resolved" [translation] (2005, 358). In articles focusing on the security situation in India for the time period 2002 to 2005, Jane's Intelligence Review (JIR) does not mention Punjab state. Rather, JIR articles focus on the activities of Maoist groups in northeastern and southeastern states of India, with no reference to militant groups in Punjab state (JIR Nov. -

Vicissitudes of Gurdwara Politics

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Vicissitudes of Gurdwara Politics YOGESH SNEHI Vol. 49, Issue No. 34, 23 Aug, 2014 Yogesh Snehi ([email protected]) is a fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla. The demand of the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee to oversee the functioning of gurdwaras represents the legitimate aspirations of the Sikhs of Haryana and more significantly, inversion against almost absolute hegemony of SAD over the management of Sikh shrines through Sikh Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee. The situation over the formation of Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (HSGPC) and the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) dominated Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee’s (SGPC) opposition to it, has entered into a confrontational stage endangering the peace and harmony in the region. Despite the enactment of the Haryana Sikh Gurdwara Act 2014, the SGPC has refused to vacate the gurdwaras in Haryana for HSGPC. While Gurdwara Chhevin Patshahi at Kurukshetra becomes the centre-stage for a long-drawn battle, HSGPC has taken possession of six gurdwaras in the state (Sedhuraman 2014).[1] After clashes between the supporters of SGPC and HSGPC, the Supreme Court has ordered maintenance of status-quo and postponed the next hearing for 25 August 2014. This recent controversy has its roots both in the movement for gurdwara reforms (1920s), which sought to purge Sikhism from the polluting effects of non-Sikh practices, as well as the reorganisation of Punjab province in 1966. It also raises some fundamental issues about the residue of colonialism in the 21st century India. Historicising Gurdwara Reform More than nine decades ago in 1921, Punjab was embroiled in a controversy over misuse of the premises of Gurdwara Janam Asthan at Nankana Sahib (now in Pakistan) for narrow self-interests by the hereditary custodian Udasi Mahant Narain Das who was a Sehajdari Sikh (Yong 1995: 670).[2] Mahants had traditionally inherited the custodianship of most gurdwaras since pre-colonial Punjab[3] and had allegedly started behaving like sole proprietors.