Waraweena Expedition Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![96 C.L.R.] of Australia. 563 Elder's Trustee And](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6383/96-c-l-r-of-australia-563-elders-trustee-and-66383.webp)

96 C.L.R.] of Australia. 563 Elder's Trustee And

96 C.L.R.] OF AUSTRALIA. 563 [HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA.] ELDER'S TRUSTEE AND EXECUTORY APPELLANT ; COMPANY LIMITED . ./ AND FEDERAL COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION RESPONDENT. Estate Duty {Cth.)—Company shares—Valuation—Principles to be applied—Com- H. C. OF A. pany engaged in pastoral pursuits in semi-arid areas—-Weight to be attached to 1951. results in past years—-Allowance for reserves—Estate Duty Assessment Act 1914-1942. Adelaide, Sept. 21, 24, The estate of a deceased person included a small proportion of the issued 25; shares of a company which owned and operated four grazing properties. One Sydney, property had been and one was about to be converted from sheep to cattle, Nov. 5. and the other two were sheep stations. All were in semi-arid areas and sub- ject to special hazards. The company's shares were not quoted on a stock Kitto J. exchange. Held that in applying ordinary principles of valuation to the valuation of shares, it should be recognised that ordinarily a purchaser is likely to be influenced, as to price, mainly by his opinion concerning the dividends which the shares may reasonably be expected to produce. In the present case, having regard to the nature and characteristics of the company's business, a hypothetical purchaser buying at the date of death of the deceased would have looked for a high assets-backmg for the shares, as well as for a high average dividend arrived at after making substantial allowances for reserves. The selection of suitable test periods, and the adjustments to be made in using the company's accounts of the selected periods in order to estimate the profits which might have been regarded at the date of death as likely to be made by the company in the future, considered. -

Vol No Artist Title Date Medium Comments 1 Acraman, William

Tregenza PRG 1336 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL PICTURES INDEX ARTIST INDEX (Series 1) (Information taken from photo - some spellings may be incorrect) Vol No Artist Title Date Medium Comments 1 Acraman, William Residence of E Castle Esq re Hackham Morphett Vale 1856 Pencil 1 Adamson, James Hazel Early South Australian view 1 Adamson, James Hazel Lady Augusta & Eureka Capt Cadell's first vessels on Murray 1853 Lithograph 1 Adamson, James Hazel The Goolwa 1853 Lithograph 1 Adamson, James Hazel Agricultural show at Frome Road 1853 W/c 1 Adamson, James Hazel Jetty at Port Noarlunga with Yatala in background 1855 W/c 1 Adamson, James Hazel Panorama of Goolwa from water showing Steamer Lady Augusta 1854 Pencil & wash No photo 1 Angas, George French SA Illustrated photocopies of plates List in front 1 Angas, George French Portraits (2) 1 Angas, George French Devil's Punch Bowl 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Encounter Bay looking south 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Interior of crater, Mount Shanck 1844 W/c Plus current 1 Angas, George French Lake Albert 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Mt Lofty from Rapid Bay W/c 1 Angas, George French Interior of Principal Crater Mt Gambier - evening 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Penguin Island near Rivoli Bay 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Port Adelaide 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Port Lincoln from Winter's Hill 1845 W/c 1 Angas, George French Scene of the Coorong at the Narrows 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French The Goolwa - evening W/c 1 Angas, George French Sea mouth of the Murray 1844-45 W/c 1 Angas, -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Monuments and Memorials

RGSSA Memorials w-c © RGSSA Memorials As at 13-July-2011 RGSSA Sources Commemorating Location Memorial Type Publication Volume Page(s) Comments West Terrace Auld's headstone refurbished with RGSSA/ACC Auld, William Patrick, Grave GeoNews Geonews June/July 2009 24 Cemetery Grants P Bowyer supervising Plaque on North Terrace façade of Parliament House unveiled by Governor Norrie in the Australian Federation Convention Adelaide, Parliament Plaque The Proceedings (52) 63 presences of a representative gathering of Meeting House, descendants of the 1897 Adelaide meeting - inscription Flinders Ranges, Depot Society Bicentenary project monument and plaque Babbage, B.H., Monument & Plaque Annual Report (AR 1987-88) Creek, to Babbage and others Geonews Unveiled by Philip Flood May 2000, Australian Banks, Sir Joseph, Lincoln Cathedral Wooden carved plaque GeoNews November/December 21 High Commissioner 2002 Research for District Council of Encounter Bay for Barker, Captain Collett, Encounter bay Memorial The Proceedings (38) 50 memorial to the discovery of the Inman River Barker, Captain Collett, Hindmarsh Island Tablet The Proceedings (30) 15-16 Memorial proposed on the island - tablet presented Barker, Captain Collett, Hindmarsh Island Tablet The Proceedings (32) 15-16 Erection of a memorial tablet K. Crilly 1997 others from 1998 Page 1 of 87 Pages - also refer to the web indexes to GeoNews and the SA Geographical Journal RGSSA Memorials w-c © RGSSA Memorials As at 13-July-2011 RGSSA Sources Commemorating Location Memorial Type Publication Volume -

Rare Books Lib

RBTH 2239 RARE BOOKS LIB. S The University of Sydney Copyright and use of this thesis This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copynght Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act gran~s the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author's moral rights if you: • fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work • attribute this thesis to another author • subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author's reputation For further information contact the University's Director of Copyright Services Telephone: 02 9351 2991 e-mail: [email protected] Camels, Ships and Trains: Translation Across the 'Indian Archipelago,' 1860- 1930 Samia Khatun A thesis submitted in fuUUment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University of Sydney March 2012 I Abstract In this thesis I pose the questions: What if historians of the Australian region began to read materials that are not in English? What places become visible beyond the territorial definitions of British settler colony and 'White Australia'? What past geographies could we reconstruct through historical prose? From the 1860s there emerged a circuit of camels, ships and trains connecting Australian deserts to the Indian Ocean world and British Indian ports. -

Northern Flinders Ranges

A B Oodnadatta Track C D Innamincka E F Birdsville Track Strzelecki ROAD CONDITIONS The road surface information on this map Track should be used as a guide only. Local TRACK advice should be sought at all times. LAKES Frome With very few exceptions, the lakes STRZELECKI Arkaroola Paralana 'Mt Lyndhurst' Wilderness Hot Springs 1 shown are dry salt pans and do not Ochre Pits Sanctuary 'North Mulga' 1 indicate a permanent source of water. 'Avondale' 'Umberatana' Mt Painter PASTORAL PROPERTIES Lyndhurst The roads in this region pass through Talc Alf Echo Camp working pastoral properties. Please do Backtrack Barraranna Gorge not leave the road and enter these River 4WD properties without prior permission from Arkaroola 'Yankaninna' Ochre the landholder. Most home steads do Wall not provide tourist facilities and are 83 Wooltana shown on this map for navigational Vulkathunha - Cave purposes. Please respect the property 33 Mainwater Pound and privacy of pastoralists. 'Owieandana' 'Wooltana' Coaleld Illinawortina 'Myrtle Springs' Gammon Ranges 30 4WD TRACKS National Park Pound For more information on 4WD Tracks Gerti Johnson Nepouie please obtain a copy of the 4WD Tracks 'Leigh Monument Weetootla Gorge 2 & Repeater Towers brochure. You may Creek' Balcanoona Gorge 2 need to make an appointment and pay Ck 'Depot NEPABUNNA access fees for some tracks. Copley 45 Springs' ABORIGINAL LAND Leigh Creek Nepabunna Balcanoona Aroona Dam 'Angepena' 54 Italowie Nat. Park H.Q. Fence Arrunha Aroona Iga Warta Gorge Sanctuary 'Maynards Vulkathunha - Gammon Ranges Well' National Park Puttapa 'Wertaloona' Copper King Mine Puttapa Moro Gorge Gap HWY NANTAWARRINA Ediacara 'Warraweena' INDIGENOUS Dog Lake Conservation Lake Reserve Afghan PROTECTED AREA 39 Mon. -

Rex Ellis' Flinders Ranges Safari

Rex Ellis’ PO Box 459, Waikerie, S.A. 5330 Ph: (08) 85432280 Email: [email protected] Website: www.safarico.com.au 4WD ~ Camels ~ Boats Rex Ellis’ Flinders Ranges Safari (4WD) 7 days / 7 nights Fully accommodated This itinerary begins on the afternoon before Day 1. It departs Rex Ellis’ property on the River Murray, between Waikerie and Morgan, at 4pm. Guests can travel Adelaide to Waikerie by coach, where they are picked up, or drive own vehicles to property. Afternoon tea is enjoyed on spectacular cliffs overlooking the river, before departing via Morgan and Burra for Jamestown. Following a two course meal at the Jamestown Hotel, we travel on to our accommodation at Carrieton. Day 1 To Hawker. Visit Jeff Morgan Gallery to experience his remarkable panoramas, etc. Visit Aboriginal rock art site or birding location (depending on clients’ interest). Drive scenic route between Elder Range and Wilpena Pound, before arriving at Merna Mora (a working sheep station). Day 2 Visit Lake Torrens, the world’s longest saltlake (when extra daylight available, this can occur on Day 1). To Flinders Ranges National Park, visiting the ruggedly spectacular Brachina Gorge and Aroona Valley. To Warragundi, Rex Ellis’ private wildlife reserve near the township of Blinman (South Australia’s highest town). Alternatively via Parachilna (the famous Prairie Hotel), then via Parachilna Gorge and Angorichina Tourist Village, to *Warragundi and on to Blinman. O/N accommodation at the Blinman Hotel, one of Australia’s special ‘bush pubs’. * A steep 4WD track is taken to the camp, located in high rugged range country, with much of interest. -

SA Arid Lands

June 2014 Issue 70 ACROSS THE OUTBACK SA Arid Lands: ‘It’s your 01 BOARD NEWS 02 Help is on the way for drought affected properties in place – tell us what matters South Australia 03 NRM Board tours region 03 Pastoral Board hosts open forum to you!’ in Glendambo 05 LAND MANAGEMENT The SA Arid Lands community is being asked to share their 06 LambEx 2014 motivates and informs treasured spots and their childhood memories — and it’s land managers 07 Wirrealpa and Willow Springs host all about taking a new approach to planning for the future EMU™ Field Day of the region. 08 VOLUNTEERS The SA Arid Lands (SAAL) Natural Resources This is why we have a Regional NRM Plan, 08 The Great Tracks Clean Up Crew get Management (NRM) Board has taken its to articulate our goals and to set the off the beaten track first step in working with the community direction of natural resource management to develop the new Regional NRM Plan, for the region.’ 09 WATER MANAGEMENT launching ‘It’s your place’, a campaign that While there is an existing Plan in place, 09 Managing South Australia’s encourages community to come together to it needs updating to account for climate Diamantina River catchment talk about what makes the SA Arid Lands change as well as legislative, policy and 10 THREATENED FAUNA region such a special place. organisational changes, so the SAAL NRM 10 Trial Western Quoll release – an ‘The role of the NRM Board is to champion Board is using the opportunity to improve update sustainable use of our natural resources — community input and ownership. -

If South Australia Must Import Her Names, Let Her Select Those Not Likely to Induce a Babel of Increased Confusion

E If South Australia must import her names, let her select those not likely to induce a babel of increased confusion. (Register 16 July 1907, page 6h) Eagle Nest Hills - Near the Siccus River, named by E.C. Frome in 1843 because of an eagle nest found close to the summit, ‘comprised chiefly of slate of a reddish hue.’ It is not shown on contemporary maps and, in 1858, the surveyor Samuel Parry said it was ‘a pretty name and ought to be retained, but the hill being now known as “Mount Chambers”… I must, against my will, retain Chambers.’ Eagle on the Hill - In 1853, William Anderson was licensee of the ‘Anderson Hotel’ that was changed to its present name when the owner had a live eagle perched on a pole. Later, in 1883, it was described as ‘where a representative eagle-hawk, caged and contemplative, sits in solitary dignity, regretting some far-distant sheep run where he was wont to swoop upon the shepherd’s charge and make his meal of raw lamb chops’: The hotel was built by George Stevenson in 1850 and, in the first instance, was owned as an eating house by William Oliver. Its principal patrons were the first toilers of the hills - the bullock drivers. It was first licensed in 1852, the licensee being Mr. Gepp, the well known boniface of the Rock Tavern, near Grove Hill. Under Mr. Fordham’s proprietorship it was, in the first instance, christened ‘Anderson’s Inn’. Upon his death in 1864 when ‘his strength was completely exhausted by a carbuncle in the shoulder’, his wife and son carried on the proprietorship until December 1873. -

Vadhalinha Von Doussa

V Many of the changes that have already taken place show that, despite early or local associations, improvements are commonly welcomed and gradually prevail. (Advertiser, 17 September 1900, page 4d) Vadhalinha Gorge - East of Beltana; Aboriginal for ‘like a grub’. Vailima Court - A subdivision of part section 256, Hundred of Adelaide, by Carl H.W. Nitschke, licensed victualler, in 1918; now included in Hackney. The original plan shows ‘Elm Court’. Vale Park - Takes its name from ‘Vale House’, purchased by Philip Levi in November 1856. In November 1947 the last surviving member of the family, Constance Levi, offered the house and ten acres of land to the Walkerville Corporation for the purpose of a public park, known, today, as ‘Levi Park’. In 1838, at the age of sixteen years, Phillip Levi arrived in Australia from Surrey in the Eden. His first job was taken with the Customs Department, but he soon combined pastoral activities with mercantile pursuits. He opened the commercial house of Philip Levi & Co. at the corner of King William and Grenfell Streets, Adelaide, where the old Imperial Hotel stood. That locality was known for many years as ‘Levi’s Corner’. For more than half a century Philip Levi, who in his early youth devoted much time and work to opening up the north, was one of the most familiar figures in Adelaide. Grazing his first flock of sheep over the now thickly populated suburbs of Prospect and Walkerville, Levi… acquired ‘Dust Holes’ near Truro. A man of remarkable energy and financial ability, with a daring speculative spirit, tempered with sound judgement, Levi, most of whose ventures were brought to a successful issue, speedily made a large fortune. -

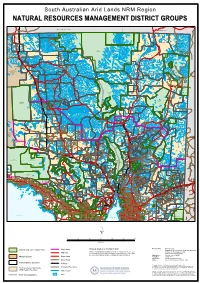

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

M01: Mineral Exploration Licence Applications

M01 Mineral Exploration Licence Applications 27 September 2021 Resources and Energy Group L4 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide SA 5000 http://energymining.sa.gov.au/minerals GPO Box 320, ADELAIDE, SA 5001 http://energymining.sa.gov.au/energy_resources Phone +61 8 8463 3000 http://map.sarig.sa.gov.au Email [email protected] Earth Resources Information Sheet - M1 Printed on: 27/09/2021 M01: Mineral Exploration Licence Applications Year Lodged: 1996 File Ref. Applicant Locality Fee Zone Area (km2 ) 250K Map 1996/00118 NiCul Minerals Limited Mount Harcus area - Approx 400km 2,415 Lindsay, WNW of Marla Woodroffe 1996/00185 NiCul Minerals Limited Willugudinna Hill area - Approx 823 Everard 50km NW of Marla 1996/00260 Goldsearch Ltd Ernabella South area - Approx 519 Alberga 180km NW of Marla 1996/00262 Goldsearch Ltd Marble Hill area - Approx 80km NW 463 Abminga, of Marla Alberga 1996/00340 Goldsearch Ltd Birksgate Range area - Approx 2,198 Birksgate 380km W of Marla 1996/00341 Goldsearch Ltd Ayliffe Hill area - Approx 220km NW 1,230 Woodroffe of Marla 1996/00342 Goldsearch Ltd Musgrave Ranges area - Approx 2,136 Alberga 180km NW of Marla 1996/00534 Caytale Pty Ltd Bull Hill area - Approx 240km NW of 1,783 Woodroffe Marla Year Lodged: 1997 File Ref. Applicant Locality Fee Zone Area (km2 ) 250K Map 1997/00040 Minex (Aust) Pty Ltd Bowden Hill area - Approx 300 WNW 1,507 Woodroffe of Marla 1997/00053 Mithril Resources Limited Mt Cooperina Area - approx. 360 km 1,013 Mann WNW of Marla 1997/00055 Mithril Resources Limited Oonmooninna Hill Area - approx.