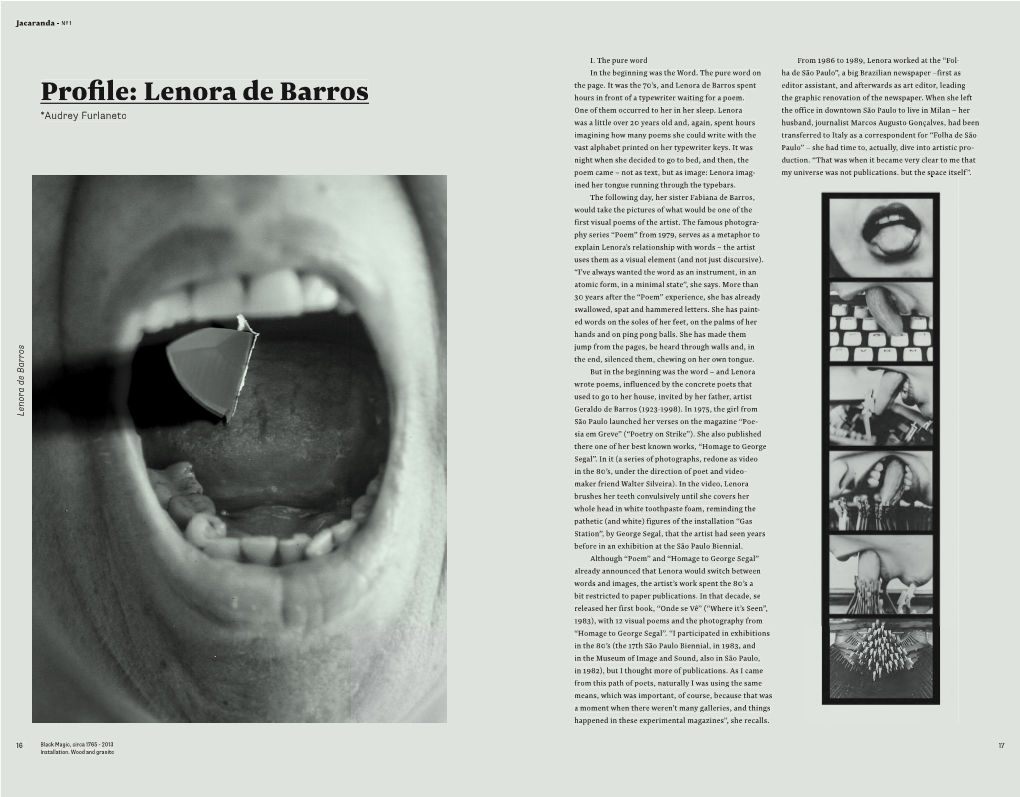

Lenora De Barros Spent Editor Assistant, and Afterwards As Art Editor, Leading Profi Le: Lenora De Barros Hours in Front of a Typewriter Waiting for a Poem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Koller Photographie Auktion: Dienstag, 4. Dezember 2018, 16.00

Auktion: 4. Dezember 2018 PHOTOGRAPHIE Photographie Lot 1601- 1792 Auktion: Dienstag, 4. Dezember 2018, 16.00 Uhr Vorbesichtigung: Mi. 28. November – So. 2. Dezember 2018, 10 – 18 Uhr Do. 29. November, 10 – 21 Uhr Do. 29. November, 10 – 21 Uhr Historische Photographie 1601-1606 Helvetica 1607-1619 Klassische Photographie 1620-1726 Portraits und Mode-Photographie 1721-1743 Zeitgenössische Photographie 1744-1792 Gabriel Müller, M.A. Tel. +41 44 445 63 40 [email protected] Aus Gestaltungsgründen können einzelne Photographien im Katalog beschnitten abgebildet sein. Auf unserer Website finden Sie die Abbildungen aller Objekte in unbeschnittenem Zustand: www.kollerauktionen.ch Der Zustand der Werke ist im Katalog nur zum Teil und in Einzelfällen angegeben. Gerne senden wir ihnen einen ausführlichen Zustandsbericht zu. English descriptions upon request. Photographie | Historische Photographie Der gebürtige Franzose Jean-Gabriel Eynard, einflussreicher Politiker und Finanzier, beschäftigte sich zirka von 1840 bis 1860 mit dem Verfahren der Daguerreotypie. Von ihm sind rund 200 qualitativ hoch stehende Daguerreotypien erhalten. Die vorliegende Aufnahme entstand wohl 1850 vor der Villa Choisi in Beaulieu bei Rolle (VD). Eynard hatte die spezielle Vorliebe Zusammenkünfte mit einem Grup- penbild zu krönen, bei denen er sich stets unter die Portraitierten zu mischen pflegte. Hier stellt er sich zusammen mit Mitgliedern der berühmten Bankier-Familie De Lessert dar (Armand De Lessert, Paul De Lessert und dessen Gattin), die ebenfalls einige Pioniere der Photographie hervorbrachte. 1601 JEAN-GABRIEL EYNARD (1775-1863) Selbstportrait mit der Familie De Lessert, 1850. Daguerreotypie. Ausschnitt 11 x 14,5 cm (Lichtmass), Gesamtgrösse 17 x 21,2 cm. Ver- so alte handschriftliche Bezeichnung und Datierung. -

Clique Aqui Para Baixar O Catálogo Galeria Expandida

analívia cordeiro fabiana de barros gilbertto prado lucas bambozzi regina silveira ricardo basbaum ana paula lobo bruno faria cláudio bueno denise agassi esqueleto coletivo paula garcia concepção e curadoria de Christine Mello galeria expandida concepção e curadoria de Christine Mello assistência curatorial: Ananda Carvalho e Paula Garcia realização: Luciana Brito Galeria período: 05/04 a 20/04 de 2010 galeria expandida é uma plataforma curatorial que reflete sobre circuitos da arte e da mídia. Baseada em artistas que promovem ações mi- diáticas, discute espaços de visibilidade na arte. Em um contexto em que a produção artística é por natureza desmaterializada e transitória, a pergunta que transpassa é como abrigar tal produção numa galeria de arte? A idéia de expansão da galeria diz respeito a nela provocar uma situação de pesquisa e um espaço de reflexão que incitem situações de interação e de- bate sobre a circulação da obra em circunstâncias imateriais e imprevisíveis, para além do seu espaço físico. A operação curatorial traz para dentro da galeria trabalhos que geralmente ocorrem em ambientes fora dela, acontecem no espaço público, de natureza efêmera e midiática. Ao possibilitar uma contra-circulação desses trabalhos em seus ambientes, sugere que a galeria se expanda como um ambiente de relações e trocas, como um fluxo informacional. O conceito de expansão situa-se especificamente nos cruzamentos existentes entre espaços da arte e experiências midiáticas acessíveis no nosso cotidiano (como as promovidas pela internet, televisão, telefonia móvel, mídia indoor e outdoor, jornal, revistas, cartazes, filipetas, adesivos, transmissões sonoras e camisetas) que integram o universo das redes de comunicação, do circuito publicitário e das marcas. -

Fabiana De Barros & Michel Favre Fabiana De Barros Is a Swiss Artist Born in Brazil, Working Between Geneva, Switzerland

Fabiana de Barros & Michel Favre Fabiana de Barros is a Swiss artist born in Brazil, working between Geneva, Switzerland and Sao Paulo, Brazil. Michel Favre is a Swiss photographer and filmmaker based in Geneva. They work together since 1996. Fabiana de Barros creates interventions and interactive performances to establish an individual relationship with the viewer in the public space. Her Public Art attitude meets Michel Favres’ work as documentary filmmaker. They develop together a common artistic approach that is a natural combination of their skills and postures, both in real life and its representation, focusing on the multiple interactions between the artist and its audience. Main exhibitions and common works 2012 CIDADE GATO QUENTE, Installation, Eternal Tour in São Paulo, BR 2011 SAUDADE, Vidéo HD, 3 minutes, Rita Production, Geneva, CH 2010 BIENNALE DE BIWAKO, installation, JP PIC-NIC ANTHROPOPHAGE, La Comédie de Geneva – lecture, CH 2009 FIN DU MONDE, Topographie de l’Art, Paris, F TREE DANCE ON SECOND LIFE, video - 10 min – silent ÇA VA ?, video - 19 min HOME, Installation, Galeria Luciana Brito, São Paulo, BR 2008 ULTRA - NONSTOP, Installation, Assab One Gallery, Milano, I MULTIPLICIDADE, Performance AV, Fiteiro Doc Live, Rio de Janeiro, BR MÃO DUPLA, video, SESC Pinheiros, São Paulo, BR MAPPING’08, Performance AV , Fiteiro Doc Live, Genève, CH PRINT, video – loop - 8 min MOVE, video – loop - 33 min 2006 1° BIENAL DAS CANARIAS, Las Palmas, Canarias, SP ESPACIO ABIERTO, Installation HOT SPOT, Buenos Aires, ARG L’IMAGE À PAROLES, long-feature documentary – 90 min STOPOVER, video installation, Fri-Art, Fribourg, CH ABERTO (OPEN) OUVERT, book and video performance MAMCO Geneva, CH 2005 AUTO PSI – THE WOMEN EDITION, 2 channels video installation, 20 min. -

Geraldo De Barros O Design E a Arte Concreta No Brasil

CARLOS EDUARDO DA SILVA V ALENTE GERALDO DE BARROS O DESIGN E A ARTE CONCRETA NO BRASIL Dissertação de Mestrado em História da Arte Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Centro de Letras e Artes Escola de Belas Artes Rio de Janeiro setembro de 1998 Carlos Eduardo da Silva Valente GERALDO DE BARROS : O DESIGN E A ARTE CONCRETA NO BRASIL Dissertação de Mestrado em História da Arte Orientador: Rogério Medeiros Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Centro de Letras e Artes Escola de Belas Artes Rio de Janeiro 1998 11 V ALENTE, Carlos Eduardo da Silva Geraldo de Barros : o Design e a Arte Concreta no Brasil xiii, 218 p Dissertação : Mestrado em História da Arte (História e Crítica da Arte) 1. Design no Brasil 2.Geraldo de Barros 3. Arte Concreta I. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro II. Título iii Carlos Eduardo da Silva Valente GERALDO DE BARROS : O DESIGN E A ARTE CONCRETA NO BRASIL Dissertação submetida ao Corpo Docente da Escola de Belas Artes da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau mestre t1dd ~ ~~ · Prof Dr. Rafael Cardoso Denis Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro Rio de Janeiro Setembro de 1998 iv Dedico este trabalho a minha avó Maria Joaquina V AGRADECIMENTOS Aos meus pais Maria Augusta e Francisco Valente Aos meus tios Hélia e Manuel da Costa e Silva Ao meu irmão André Luiz da Silva Valente Aos meus amigos Kátia Meirelles e Mário Conde Aos meus professores do mestrado Maria Luiza Tavora, Angela Ancora da Luz, Rosza W.Vel Zolads e Carlos Terra As minhas amigas e professoras Ida de Jesus Ferreira e Zilda Ferreira Lustosa Ao artista Geraldo de Barros ( em memória), sua esposa Electra Barros e suas filhas Fabiana e Lenora Barros Ao designer Alexandre W ollner À minha amiga Cristine Monteiro Flores Ao meu orientador Rogério Medeiros vi GERALDO DE BARROS: O DESIGN E A ARTE CONCRETA NO BRASIL Este trabalho procura mostrar como a Arte Concreta proporcionou, também, o desenvolvimento do design, especificamente o gráfico, no Brasil. -

JOSEPH KOSUTH ‘The Language of Equilibrium’ Monastic Headquarters of the Mekhitarian Order Island of San Lazzaro Degli Armeni, Venice

JOSEPH KOSUTH ‘The Language of Equilibrium’ Monastic Headquarters of the Mekhitarian Order Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, Venice Curated by Adelina von Fürstenberg A project by ART for The World, Geneva – Milan, NGO associated with the United Nations Department of Public Information In collaboration with Hangar Bicocca, Spazio d’Arte Contemporanea, Milan Opening: June 6, from 6:30 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. Vaporetto n. 20 from San Zaccaria, departure at 6:30 and 7:50 p.m. On June 6-7-8-9 a boat service will be available from Giardini to the Island of San Lazzaro. Dates: June 10 – November 21, 2007 Public opening hours of the Monastic Headquarters of the Mekhitarian Order: every day from 3:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. How to reach the Island of San Lazzaro: Vaporetto n. 20 Vaporetto timetable: from San Zaccaria to San Lazzaro h. 3:10 p.m. from San Lazzaro to San Zaccaria h. 4:45 p.m. or 5:25 p.m. Press Office: Mara Vitali Comunicazione – Lucia Crespi T. +39 02 73950962, cell. +39 338 8090545, email: [email protected] The Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni is the location for a project by Joseph Kosuth, entitled The Language of Equilibrium, collateral event of the 52nd International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia. At the invitation of Adelina von Fürstenberg, the founder of ART for The World, Joseph Kosuth has intervened on different parts of the island, along the external perimeter wall to the observatory, from the promontory to the bell tower. -

Photography and the Construction of São Paulo, 1930–1955

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Framing the City: Photography and the Construction of São Paulo, 1930–1955 Danielle J. Stewart The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3273 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FRAMING THE CITY: PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF SÃO PAULO, 1930-1955 by DANIELLE STEWART A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 DANIELLE STEWART All Rights Reserved !ii Framing the City: Photography and the Construction of São Paulo, 1930-1955 by Danielle Stewart This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ ________________________________ Date Anna Indych-López Chair of Examining Committee __________________ ________________________________ Date Rachel Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Katherine Manthorne M. Antonella Pelizzari Edward J. Sullivan THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK !iii ABSTRACT Framing the City: Photography and the Construction of São Paulo, 1930-1955 by Danielle Stewart Advisor: Anna Indych-López Between 1930 and 1955 São Paulo, Brazil experienced a period of accelerated growth as the population nearly quadrupled from 550,000 to two million. -

Estamos Aqui Web.Pdf

Museu de Arte Contemporânea do Paraná 15 de maio a 11 de agosto de 2019 2 3 EXPOSIÇÃO 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 TEXTOS O protagonismo das mulheres nas artes visuais e na arte como Com a consolidação do museu e a promoção do mais um todo é essencial em um contexto, no qual instituições importante prêmio de artes do Estado, o Salão Paranaense, museais do mundo todo têm, em seus acervos, mais obras que permitiu ao MAC-PR incorporar ao seu acervo artistas e trabalhos realizados por homens. Sem exceção, esta não do Brasil, da América Latina e de outros países do mundo, o é só uma realidade brasileira, mas global. Por isso, exposições nosso principal compromisso é dar continuidade à diversidade como “Estamos aqui!”, que reúne somente obras de mulheres para a sua coleção de 1,8 mil obras. A busca é, sobretudo, artistas do acervo e convidadas, são um passo para equilibrar pelo equilíbrio entre obras de homens e mulheres: hoje, a essas diferenças. discrepância entre os gêneros chega a 786 trabalhos. A iniciativa está em total consonância com a história do Museu Seguimos rumo aos 50 anos com planos para envolver cada de Arte Contemporânea do Paraná, que chega aos seus vez mais a comunidade no museu, colocar as mulheres artistas 50 anos em 2020: criado em 11 de março de 1970 por decreto como agentes e continuar trabalhando na formação de um oficial, o MAC-PR como o conhecemos hoje só foi possível pela acervo plural. -

Heres D’Apolo/Apollo’S Women Year of Production: 2010 PREMIERE Presentation Medium: 16:9 Video Duration: 18’ Edition: 5

CREDITS Directors Festival Fair & Guest Program Emilio Álvarez Alexandra Laudo Sol García Galland Carlos Durán Inés Jover Andréa Goffre Llucià Homs University/ Festivals Program Assistants to Fair & Production Juliane Debeusscher Guest Program Isa Casanellas Ivana Krnjić Ainet Canut Media Lounge Sane van der Rijt Álvaro Bartolomé Press Technical Manager Gustavo Sánchez OFF LOOP Juan Carlos Gismero Sandra Costa Pedro Torres Marta Suriol Assistants to Festival Communication Jose Begega Anna Astals Serés Paolo Goodi Celeste Miranda Administration Ana Ramírez Pau Ferreiro Sara Tur Text editor Technical Manager Joana Hurtado Hunab Moreno Graphic Design / Web designbyreference.com SELECTED # 5 A SOURCE FOR VIDEO ART LOVERS Edited by Screen Projects Committee Head of committee Jean-Conrad Lemaître Anita Beckers Christopher Grimes Manuel de Santaren All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. © of the texts, the authors © of the images, the artists © of this edition, Screen Projects Printed and bound in Spain. selected #5 — CONTENTS Selected #5 – A Source for Video Art Lovers 6 The Artists and their Galleries in LOOP'10 9 Selected #5 – Artists 12 Selected #5 – Gallery Directory 84 Selected artists in LOOP since 2003 88 Acknowledgements 93 SELECTED #5 SELECTED #5 Una font per els amants del videoart A Source for Video Art Lovers La publicació que teniu a les vostres mans recull una selecció de treballs recents de The publication you hold in your hands brings together a selection of recent video videoart. Aquesta guia de referència per als amants de la videocreació, mostra la art works. This reference guide for video art lovers presents the selection made by tria del comitè de selecció de la fira LOOP d’enguany. -

Maio – Julho ’04 Imagem Na Capa Keith Haring

Maio – Julho ’04 Imagem na capa Keith Haring. Untitled 22 Jan 1986 (pormenor) © Estate of Keith Haring Mai-Jul’04 Escreveu-se no desdobrável da Programação do Culturgest, e tem, neste período de Maio a Julho, final de 1998, quando a Culturgest comemorava exuberante demonstração, seja na exposição de 5 anos de actividade: arte contemporânea da Índia, seja no conjunto de espectáculos e exposições em Lisboa e no “Com uma programação vocacionada para a Porto em torno da criação oriunda de uma área apresentação exclusiva de obras e de autores do geográfica a que chamámos Atlântico Negro, ou Séc. XX (...) contribuímos para que a ligação ao Mais a Sul, seja na exposição de Keith Haring ou mundo artístico contemporâneo passasse a ter um no espectáculo de O Bando ou nesses objectos carácter de normalidade. [...] singularíssimos que são Aviões e Arranha-céus, de Essa ligação ao mundo não foi estabelecida Ricky Seabra, e O Meu Braço, de Tim Crouch. apenas em relação à Europa, ao Canadá e aos Estados Unidos. Foi também, e com especial “Ninguém poderá afirmar com segurança que atenção, estabelecida com os mundos de criadores mais cultura implica mais felicidade, mas sabemos que habitualmente têm menor visibilidade. que, com menos cultura, estaremos mais próximos Na Culturgest (...) foi possível mostrar ao público do tédio, da injustiça, do subdesenvolvimento, da português exposições e espectáculos provenientes pequenez espiritual, muitas vezes até da barbárie”, dos mundos árabe, chinês, africano, cigano, etc., escreveu-se ainda na apresentação da progra- actividades que nos ajudaram a enriquecer a mação do final de 1997. As propostas que aqui vos programação e possibilitaram um contacto mais oferecemos demonstram-no. -

Paula Garcia

PAULA GARCIA paulagarcia.net https://vimeo.com/paulagarciaworks Paula Garcia São Paulo, 1975 Mini Bio Artist and researcher holds a master’s degree in Visual Arts from FASM-SP and a Bachelor of Arts from FAAP. Her research and artistic experiences focus on performance practice. She works as an artist, independent curator and project curator at MAI – Marina Abramovic Institute. Selected exhibitions/ performances: RAW - Performance - ARCA SPACES, São Paulo (2020); Terra Comunal – Marina Abramovic + MAI – Curator: Marina Abramovic and Paula Garcia – SESC Pompéia, São Paulo (2015); The artist is an explorer – Curator: Marina Abramovic – Beyeler Foundation, Basel (2014); 7 Biennial El Museo del Barrio – Curators: Chus Martinez / Rocío Aranda-Alvarado / Raúl Zamudio – El Barrio Museum, New York (2013/2014); The Big Bang : The 19th Annual Watermill Center Summer Benefit – Curator: Robert Wilson – Walter Mill, New York (2012); 17º International Festival of Contemporary Art Videobrasil_SESC – SESC Belenzinho – SP; Performa Paço in Paço das Artes – SP – (2011); 6th edition of the Exhibition Annual Performance Vermelho Gallery – SP (2010), “Expanded Gallery” on Luciana Brito Gallery – SP (2010). Selected curatorial projects: Curação - São Paulo Cultural Center, São Paulo (2020); Akış / Flux – Sakip Sabanci Museum + MAI – Curators: Paula Garcia and Serge Le Borgne – SSM, Istanbul – Turkey; A Possible Island? – Bangkok Art Biennale + MAI – Curators: Paula Garcia and Serge Le Borgne – BACC, Bangkok – Thailand (2018); SP-Arte – Curator of performance program – São Paulo – Brazil (2018); As One – NEON + MAI – Curators: Serge Le Borgne and Paula Garcia – Benaki Museum, Athens – Greece (2016); Selected Exhibitions Paula Garcia São Paulo, 1975 2021 – Não vamos para marte II - Curator: Galciani Neves - Jaqueline Martins Gallery, São Paulo 2020 – RAW – Performance – ARCA, São Paulo. -

GERALDO DE BARROS B. February 27, 1923, Xavantes, São Paulo

GERALDO DE BARROS b. February 27, 1923, Xavantes, São Paulo, Brazil d. 1998, São Paulo, Brazil SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Geraldo de Barros: Unilabor, Kunst-und KulturstiftungOpelvillen Rüsselsheim, Germany Geraldo de Barros and Unilabor by DPot, Arcadia, Geneva, Switzerland Geraldo de Barros – Fotoformas, Document Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA Geraldo de Barros – That’s It, Dip Contemporary, Lugano, Switzerland 2017 Geraldo de Barros: Sobras, Document Gallery, Chicago, USA Geraldo de Barros: Fotoformas e Sobras, Fundação Arpad-Szenes/Vieira da Silva, Lisbon, Portugal 2016 Geraldo de Barros: Off Center, Sicardi Gallery, Houston, Texas Geraldo de Barros: Industrial, Galeria Luciana Brito, São Paulo, Brazil 2015 Geraldo de Barros and Photography, SESC Belezinho, São Paulo, Brazil 2014 Geraldo de Barros and Photography, Instituto Moreira Salles, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Tierney Gardarin Gallery, New York, USA 2013 Geraldo de Barros- Jogos de Dados + Sobras (1980-1990), SESC Vila Mariana, São Paulo, Brazil Geraldo de Barros: What remains? The Photographer’s Gallery, London, UK 2010 Entre Tantos: Geraldo de Barros, Caixa Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil 2009 Geraldo de Barros- Modulação de mundos, SESC Pinheiros, São Paulo, Brazil 2008 Sicardi Gallery, Houston, Texas 2007 Sobras + Fotoformas, Galeria Brito Cimino, São Paulo, Brazil Fotonoviembre 2007 – IX Bienal International de Fotografía, Centro de Fotografía Isla de Tenerife, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain Desenho Constructivista Brasiliero, Museu de Arte Moderna Rio de Janiero, Brazil Fragmentos: Modernismo na fotografia brasiliera, Galeria Bergamin, São Paulo, Brazil 2006 Brasiliana MASP – Moderna contemporanea, Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand – MASP, São Paulo, Brazil MAM [NA] OCA, Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, Brazil Concreta 56. -

Sesc Pompeia Presents the Exhibition (+ = -) Mais É Igual a Menos to Commemorate the 18Th Anniversary of Fabiana De Barros' Fiteiro Cultural

Sesc Pompeia presents the exhibition (+ = -) Mais é Igual a Menos to commemorate the 18th anniversary of Fabiana de Barros' Fiteiro Cultural Opening: March 29th (Wenesday) at 8:00 pm With the launching of the 2nd edition of Aberto [Open]: Fiteiro Cultural, by Edições Sesc São Paulo with the support of It will feature photos, films, and models of this cultural and artistic intervention project that has traveled the world, in addition to a series of reliefs being shown for the first time Fabiana de Barros is also taking part in SP-Arte, presenting a new Fiteiro Cultural under commission by Galeria Luciana Brito Beach kiosks (fiteiros culturais) in João Pessoa (PB), Cuba and Palestine From March 30 to June 18, 2017 Sesc Pompeia will be presenting Fabiana de Barros’ (+ = -) Mais é Igual a Menos [More is Less] in the cultural center's Creativity Workshops. This free exhibition commemorates the 18th anniversary of Fiteiro Cultural, a cultural and artistic intervention conceived in 1998 that has toured 13 countries, posing new ways of thinking about the relationship between art and the public. While an artist in residence in João Pessoa, in the northeastern state of Paraiba, Fabiana de Barros created the first Fiteiro Cultural based on local beach kiosks (fiteiros). The basic wooden construction became a powerful instrument for forging collaborative cultural partnerships once they had been installed, enabling the local community to use the empty space as an workshop, a creative art center or a stage for performances, among countless other possibilities. Ever since then Barros, a Brazilian artist based in Switzerland, went on to receive several commissions from artists, institutions, galleries and international events to show her kiosks all over the world.