Rapid Detection of Plum Pox Virus from Plant Samples Using Polymerase Chain Reaction Christine Dobbin1, Won-Sik Kim1 and Yousef Haj-Ahmad1,2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Tunnel Pest Management - Aphids

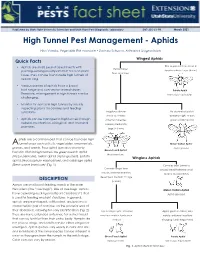

Published by Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory ENT-225-21-PR March 2021 High Tunnel Pest Management - Aphids Nick Volesky, Vegetable IPM Associate • Zachary Schumm, Arthropod Diagnostician Winged Aphids Quick Facts • Aphids are small, pear-shaped insects with Thorax green; no abdominal Thorax darker piercing-sucking mouthparts that feed on plant dorsal markings; large (4 mm) than abdomen tissue. They can be found inside high tunnels all season long. • Various species of aphids have a broad host range and can vector several viruses. Potato Aphid Therefore, management in high tunnels can be Macrosipu euphorbiae challenging. • Monitor for aphids in high tunnels by visually inspecting plants for colonies and feeding symptoms. Irregular patch on No abdominal patch; dorsal abdomen; abdomen light to dark • Aphids can be managed in high tunnels through antennal tubercles green; small (<2 mm) cultural, mechanical, biological, and chemical swollen; medium to practices. large (> 3 mm) phids are a common pest that can be found on high Atunnel crops such as fruits, vegetables, ornamentals, Melon Cotton Aphid grasses, and weeds. Four aphid species commonly Aphis gossypii Green Peach Aphid found in Utah in high tunnels are green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Myzus persicae), melon aphid (Aphis gossypii), potato Wingless Aphids aphid (Macrosiphum euphorbiae), and cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae) (Fig. 1). Cornicles short (same as Cornicles longer than cauda); head flattened; small cauda; antennal insertions (2 mm), rounded body DESCRIPTION developed; medium to large (> 3mm) Aphids are small plant feeding insects in the order Hemiptera (the “true bugs”). Like all true bugs, aphids Melon Cotton Aphid have a piercing-sucking mouthpart (“proboscis”) that Aphis gossypii is used for feeding on plant structures. -

Biodiversity of the Natural Enemies of Aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in Northwest Turkey

Phytoparasitica https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-019-00781-8 Biodiversity of the natural enemies of aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in Northwest Turkey Şahin Kök & Željko Tomanović & Zorica Nedeljković & Derya Şenal & İsmail Kasap Received: 25 April 2019 /Accepted: 19 December 2019 # Springer Nature B.V. 2020 Abstract In the present study, the natural enemies of (Hymenoptera), as well as eight other generalist natural aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and their host plants in- enemies. In these interactions, a total of 37 aphid-natural cluding herbaceous plants, shrubs and trees were enemy associations–including 19 associations of analysed to reveal their biodiversity and disclose Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris) with natural enemies, 16 tritrophic associations in different habitats of the South associations of Therioaphis trifolii (Monell) with natural Marmara region of northwest Turkey. As a result of field enemies and two associations of Aphis craccivora Koch surveys, 58 natural enemy species associated with 43 with natural enemies–were detected on Medicago sativa aphids on 58 different host plants were identified in the L. during the sampling period. Similarly, 12 associations region between March of 2017 and November of 2018. of Myzus cerasi (Fabricius) with natural enemies were In 173 tritrophic natural enemy-aphid-host plant interac- revealed on Prunus avium (L.), along with five associa- tions including association records new for Europe and tions of Brevicoryne brassicae (Linnaeus) with natural Turkey, there were 21 representatives of the family enemies (including mostly parasitoid individuals) on Coccinellidae (Coleoptera), 14 of the family Syrphidae Brassica oleracea L. Also in the study, reduviids of the (Diptera) and 15 of the subfamily Aphidiinae species Zelus renardii (Kolenati) are reported for the first time as new potential aphid biocontrol agents in Turkey. -

Scope: Munis Entomology & Zoology Publishes a Wide Variety of Papers

262 _____________ Mun. Ent. Zool. Vol. 8, No. 1, January 2013___________ REVISION OF GENUS BRACHYCAUDUS AND NEW RECORD SPECIES ADDED TO APHID FAUNA OF EGYPT (HEMIPTERA: STERNORRHYNCHA: APHIDIDAE) A. H. Amin*, K. A. Draz** and R. M. Tabikha** * Plant Protection Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University, EGYPT. ** Pest Control and Environment Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Alexandria University, Damanhour Branch, EGYPT. [Amin, A. H., Draz, K. A. & Tabikha, R. M. 2013. Revision of genus Brachycaudus and new record species added to aphid fauna of Egypt (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aphididae). Munis Entomology & Zoology, 8 (1): 262-266] ABSTRACT: A new aphid species, Brachycaudus (Appelia) shwartzi (Borner) was recorded for the first time in Egypt during the present work. This species was heavily infested leaves of apricot, Prunus armeniaca and peaches Prunus persica during May, 2006 at El-Tahrir, El- Behera Governorate. Identification procedure was confirmed by Prof. R. Blackman at British Museum, in London. Brief verbal and drafting description for alate viviparous female of this new recorded species was carried out. Moreover a simple bracket key was constructed to identify the three recorded species of genus Brachycaudus in Egypt. KEY WORDS: Brachycaudus, Aphididae, Egypt. Family Aphididae is one of the most important groups of Aphidoidea which contain more than 4400 aphid species placed in 493 genera, and is considered as one of the most prolific groups of insects. They are capable not only rapid increase of population though parthenogenesis but also transmission of plant viral diseases and secreting honey dew which become suitable media for sooty moulds, so they are regarded as one of the most important groups of agricultural pests. -

The Phytophagous Insect Fauna of Scotch Thistle, Onopordum Acanthium L., in Southeastern Washington and Northwestern Idaho

Proceedings of the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds 233 4-14 July 1999, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, USA Neal R. Spencer [ed.]. pp. 233-239 (2000) The Phytophagous Insect Fauna of Scotch Thistle, Onopordum acanthium L., in Southeastern Washington and Northwestern Idaho J. D. WATTS1 and G. L. PIPER Department of Entomology, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington 99164-6382, USA Abstract Scotch thistle, Onopordum acanthium L. (Asteraceae: Cardueae), a plant of Eurasian origin, has become an increasingly serious pasture, rangeland, wasteland, and roadside weed in the western United States. Prior to the implementation of a biological control agent acquisition and release program, a domestic survey was carried out at 16 sites in five southeastern Washington and northwestern Idaho counties between 1995-96 to ascertain the plant’s existing entomofauna. Thirty phytophagous insect species in six orders and 17 families were found to be associated with the thistle. Hemiptera, Homoptera, and Coleoptera were the dominant ectophagous taxa, encompassing 50, 20, and 17% of all species found, respectively. The family Miridae contained 60% of the hemipteran fauna. Onopordum herbivores were polyphagous ectophages, and none of them reduced popula- tions of or caused appreciable damage to the plant. The only insect that consistently fed and reproduced on O. acanthium was the aphid Brachycaudus cardui (L.). A notable gap in resource use was the absence of endophages, particularly those attacking the capitula, stems, and roots. Consequently, the importation of a complex of nonindigenous, niche- specific natural enemies may prove to be a highly rewarding undertaking. Key Words: Onopordum, Scotch thistle, weed, biological control, entomofauna Scotch thistle, Onopordum acanthium L. -

And Their Aphid Partners (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Mashhad Region, Razavi Khorasan Province, with New Records of Aphids and Ant Species for Fauna of Iran

ISSN 0973-1555(Print) ISSN 2348-7372(Online) HALTERES, Volume 6, 4-12, 2015 ZOHREH SADAT MORTAZAVI, HUSSEIN SADEGHI, NIHAT AKTAC, ŁUKASZ DEPA AND LIDA FEKRAT Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and their aphid partners (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Mashhad region, Razavi Khorasan Province, with new records of aphids and ant species for Fauna of Iran Zohreh Sadat Mortazavi1, Hussein Sadeghi1*, Nihat Aktac2, Łukasz Depa3, Lida Fekrat1 1 Department of Plant Protection, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran 2 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Trakya University, Turkey 3Department of Zoology, University of Silesia, Bankowa 9, 40-007 Katowice, Poland (e-mail: *[email protected]) Abstract A survey of ant-aphid associations was conducted by collecting and identifying samples of ants and aphids found together on aphid host plants in Mashhad region, Razavi Khorasan province of Iran. As a result, a total of 21 ant species representing 13 genera and 3 subfamilies and 26 aphid species belonging to 13 genera from 37 host plant species were collected and identified. Among the recorded ant species, the genus Crematogaster with four species had the highest species richness. The three most frequent aphid attendant ants were Lepisiota nigra (Dalla Torre, 1893), Tapinoma erraticum (Latreille, 1798) and Crematogaster inermis Mayr, 1862 associated with 11, 10 and 9 aphid species, respectively. Eleven ant species were recorded from the colonies of one aphid species. Among the recorded ants, the species Crematogaster sordidula (Nylander, 1849) is new to Iranian ant fauna. This record increases the recorded ant-fauna of Iran to over 171 species. Among the identified aphid species, Aphis craccivora Koch, 1856 had the highest ant attraction. -

Host Specialization of Parasitoids and Their Hyperparasitoids on a Pair of Syntopic Aphid Species

Research Collection Journal Article Host specialization of parasitoids and their hyperparasitoids on a pair of syntopic aphid species Author(s): Schär, Sämi; Vorburger, Christoph Publication Date: 2013-10 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000071788 Originally published in: Bulletin of Entomological Research 103(5), http://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485313000114 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Bulletin of Entomological Research (2013) 103, 530–537 doi:10.1017/S0007485313000114 © Cambridge University Press 2013 Host specialization of parasitoids and their hyperparasitoids on a pair of syntopic aphid species Sämi Schär1*† and Christoph Vorburger2,3 1Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, 8057 Zürich, Switzerland: 2Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zürich, Switzerland: 3EAWAG, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Überlandstrasse 133, 8600 Dübendorf, Switzerland Abstract Parasitoids of herbivorous insects have frequently evolved specialized lineages exploiting hosts occurring on different plants. This study investigated whether host specialization is also observed when closely related parasitoids exploit herbivorous hosts sharing the same host plant. The question was addressed in economically relevant aphid parasitoids of the Lysiphlebus fabarum group. They exploit two aphid species (Aphis fabae cirsiiacanthoides and Brachycaudus cardui), co-occurring in mixed colonies (syntopy) on the spear thistle (Cirsium vulgare). Two morphologically distinguishable parasitoid lineages of the genus Lysiphlebus were observed and each showed virtually perfect host specialization on one of the two aphid species in this system. From A. -

The Biology and Ecology of Brachycaudus Divaricatae Shaposhnikov (Hemiptera, Aphidoidea) on Prunus Cerasifera Ehrhart in Western Poland

JOURNAL OF PLANT PROTECTION RESEARCH Vol. 53, No. 1 (2013) DOI: 10.2478/jppr-2013-0006 THE BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY OF BRACHYCAUDUS DIVARICATAE SHAPOSHNIKOV (HEMIPTERA, APHIDOIDEA) ON PRUNUS CERASIFERA EHRHART IN WESTERN POLAND Barbara Wilkaniec1*, Agnieszka Wilkaniec2 Poznań University of Life Sciences, Dąbrowskiego 159, 60-594 Poznań, Poland 1 Department of Entomology and Environmental Protection 2 Department of Landscape Architecture Received: July 30, 2012 Accepted: October 10, 2012 Abstract: Brachycaudus divaricatae – was described by Shaposhnikov in the Middle East as a heteroecious aphid species migrating between Prunus divaricata and Melandrium album. The research conducted in Poland proved that this species can be described as ho- locyclic and monoecious. A significantly shortened development cycle with a summer-winter diapause characterizes this species in Poland. The aim of our studies was a detailed research of the species biology conducted to explain this phenomenon. Elements of the biology and ecology of the new fauna species Brachycaudus divaricatae Shap., were studied in Poland during the 2008–2010 time period. The term of spring hatching, number of generations per season, development length of particular generations, lifespan of specimen, and fecundity of particular generations were all defined. The three-year study proved that 6 to 8 aphid generations can develop on P. cerasifera in Poland. The emergence of sexuales (amphigonic females and males) of B. divaricatae occurred very early in the season: in mid-May, and the first eggs were laid in June. Key words: Brachycaudus divaricatae, cherry plum, demographic parameters, fecundity, life cycle INTRODUCTION m) in the garden of the Department of Entomology, Uni- So far, 4 species of Brachycaudus van der Goot, 1913 versity of Life Sciences, Poznań, Poland, in the 2008–2010 have been reported from plums (Prunus spp.) in Poland, time period. -

Bitki Koruma Bülteni / Plant Protection Bulletin, 2018, 58 (1) : 47-53

Bitki Koruma Bülteni / Plant Protection Bulletin, 2018, 58 (1) : 47-53 Bitki Koruma Bülteni / Plant Protection Bulletin http://dergipark.gov.tr/bitkorb Original article The new association records on ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in the Central Province of Çanakkale Çanakkale il merkezinde yaprakbitleri (Hemiptera: Aphididae) ile karınca (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) türlerinin yeni ilişki kayıtları a* b c a Şahin KÖK , Nihat AKTAÇ , Işıl ÖZDEMİR , İsmail KASAP a Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Plant Protection, 17020, Çanakkale, Turkey b Trakya University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, 22030, Edirne, Turkey c Plant Protection Central Research Institute, 06172, Ankara, Turkey ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Aphid and ant species have a mutualistic or an obligately mutualistic association DOI: 10.16955/bitkorb.344864 in nature conditions. Many ant species protect soft-bodied aphids with a low level Received : 17.10.2017 Accepted : 20.02.2018 of defense against their natural enemies. This study was conducted to determine the associations between aphid and ant species from 2014 to 2015 in the Center of Çanakkale Province and 12 ant species belonging to 8 genera in Dolichoderinae, Keywords: Formicinae and Myrmicinae subfamilies of Formicidae associated with 16 aphid Aphid, ant, mutualism, Çanakkale, Turkey species were determined. The most encountered ant species associated with different aphids were Lasius alienus (Foerster, 1850), Plagiolepis pygmaea * Corresponding author: Şahin KÖK (Latreille, 1798), Camponotus aethiops Latreille, 1798 and Plagiolepis taurica [email protected] Santsci, 1920. The most encountered aphid species associated with different ant species, were; Aphis fabae Scopoli, 1763, Aphis gossypii Glover, 1877 and Aphis craccivora Koch, 1854. -

Potential Role of Fruit Intercrops in Integrated Apple Aphid Management

Potential role of fruit intercrops in integrated apple aphid management Ammar Alhmedi1, Stijn Raymaekers1, Dany Bylemans1,2 & Tim Belien1 1 pcfruit vzw, Department of Zoology, Fruittuinweg 1, 3800 Sint-Truiden, Belgium; 2 KULeuven, Department of Biosystems, 3001 Leuven, Belgium Introduction Methodology Apple aphids, especially Dysaphis plantaginea Passerini, are among the most abundant and destructive To achieve the principal goal of this study, we started by monitoring the seasonal activity of aphids and insect pests of apple tree crops in Belgium, but also in all temperate regions. Their feeding can damage their natural enemies during the 2014-2015 growing seasons in several woody and herbaceous plant the crop and decrease the yield quality and quantity. Managing these pests by conventional farming and habitats including apple orchards and the associated flora. monocropping systems have been often caused a series of environmental problems. Based on our monitoring data obtained during 2014-2015, we investigated the potential of a fruit Developing and implementing fruit intercrop system to enhance the biological control of apple aphids intercrop system to control aphids in the apple orchard. requires detailed basic knowledge of tritrophic interactions among plants, aphids and natural enemies. This study was carried out in the eastern part of Belgium, Limburg province, using visual observation The potential of aphids associated with different kinds of plant habitats, more particularly fruit tree techniques. crops, as natural source -

Aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on Plum and Cherry Plum in Bulgaria

DOI: 10.2478/ahr-2020-0004 Pavlin Vasilev, Radoslav Andreev, Hristina Kutinkova Acta Horticulturae et Regiotecturae 1/2020 Acta Horticulturae et Regiotecturae 1 Nitra, Slovaca Universitas Agriculturae Nitriae, 2020, pp. 12–16 APHIDS (HEMIPTERA: APHIDIDAE) ON PLUM AND CHERRY PLUM IN BULGARIA Pavlin VASILEV*, Radoslav ANDREEV, Hristina KUTINKOVA Agricultural University, Plovdiv, Bulgaria The species complex and infestations of aphids on plum (Prunus persica) and cherry plum (Prunus cerasifera) in Bulgaria were investigated during the period 2013–2018. Nine species from the family Aphididae were found: Brachycaudus helichrysi Kaltenbach (leaf-curling plum aphid), Hyalopterus pruni Geoffroy (mealy plum aphid), Phorodon humuli Schrank (hop aphid), Brachycaudus prunicola Kaltenbach (brown plum aphid), Brachycaudus cardui Linnaeus (thistle aphid), Brachycaudus persicae Passerini (black peach aphid), Rhopalosiphum nymphaeae Linnaeus (waterlily aphid), Aphis spiraecola Patch (spiraea aphid) and Pterochloroides persicae Cholodkovsky (peach trunk aphid). The dominant species on plum are Hyalopterus pruni and Brachycaudus helichrysi. The first species is more widespread and of significantly higher density. The dominant species on cherry plum are Phorodon humuli and B. helichrysi. The species Brachycaudus prunicola is widespread both on plum and cherry plum in Bulgaria. It was found only on twigs, and therefore cannot be considered as a dangerous pest on fruit-bearing plum trees. The other species, some of them described as dangerous pests on plum, are today fairly rare and occur in low density, thus posing no danger to orchards. Keywords: Brachycaudus, Hyalopterus, Phorodon, Rhopalosiphum, Pterochloroides, Aphis In recent years, the areas with stone fruit orchards in Bulgaria the following two years – in orchards of 128 municipalities have considerably exceeded the areas with other fruit crops across all 28 districts of Bulgaria – in 2014, the southern part (Agrostatistics, 2016). -

Tc Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Antalya Ili

T.C. SÜLEYMAN DEMİREL ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ ANTALYA İLİ TURUNÇGİL BAHÇELERİNDE YAPRAKBİTİ TÜRLERİ, AVCI VE ASALAKLARININ SAPTANMASI Işıl SARAÇ Danışman Prof. Dr. İsmail KARACA YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ BİTKİ KORUMA ANABİLİM DALI ISPARTA – 2014 © 2014 [Işıl SARAÇ] İÇİNDEKİLER Sayfa İÇİNDEKİLER ............................................................................................................................ i ÖZET ............................................................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. iii TEŞEKKÜR ................................................................................................................................. iv ŞEKİLLER DİZİNİ .................................................................................................................... v ÇİZELGELER DİZİNİ .............................................................................................................. vi 1. GİRİŞ ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2. KAYNAK ÖZETLERİ .......................................................................................................... 4 3. MATERYAL VE YÖNTEM ................................................................................................ 9 3.1. Örneklerin Toplanması ......................................................................................... -

Molecular Biological Properties of New Isolates of Plum Pox Virus Strain Winona A

ISSN 0096-3925, Moscow University Biological Sciences Bulletin, 2016, Vol. 71, No. 2, pp. 71–75. © Allerton Press, Inc., 2016. Original Russian Text © A.V. Zakubanskiy, A.A. Sheveleva, S.N. Chirkov, 2016, published in Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta. Biologiya, 2016, No. 2, pp. 8–12. VIROLOGY Molecular Biological Properties of New Isolates of Plum Pox Virus Strain Winona A. V. Zakubanskiy, A. A. Sheveleva, and S. N. Chirkov* Department of Biology, Moscow State University, Moscow, 119234 Russia *e-mail: [email protected] Received December 30, 2015 Abstract—Plum pox virus (PPV, genus Potyvirus, family Potyviridae) is the most important virus pathogen of stone fruit cultures of the genus Prunus from an economical standpoint. Winona strain (PPV-W) is the most variable of nine known virus strains and one of the most widespread in the European part of Russia. Six new PPV-W isolates were first discovered in green plantations of Moscow (Kp2U, Avang, Pulk, Pulk-1), in Tal- domsky district of Moscow region (Karm), and in Kovrovsky district of Vladimir region (Vlad-4) on wild trees of plum Prunus domestica. 3'-Terminal segment of genome of new isolates was notable for high variability level. The study on the relationship with other isolates of this strain by means of phylogenetic analysis of gene sequence of the coat protein showed the lack of clusterization of Russian PPV-W isolates according to geo- graphical principle. Inoculation of Nicotiana benthamiana plants by hop plant louse Phorodon humili from plum trees infected with Avang and Pulk isolates and by thistle aphid Brachycaudus cardui from the tree infected with Kp2U isolate led to the systemic viral infection in indicator plants, suggesting the possibility of PPV-W spread by both aphid species in nature.