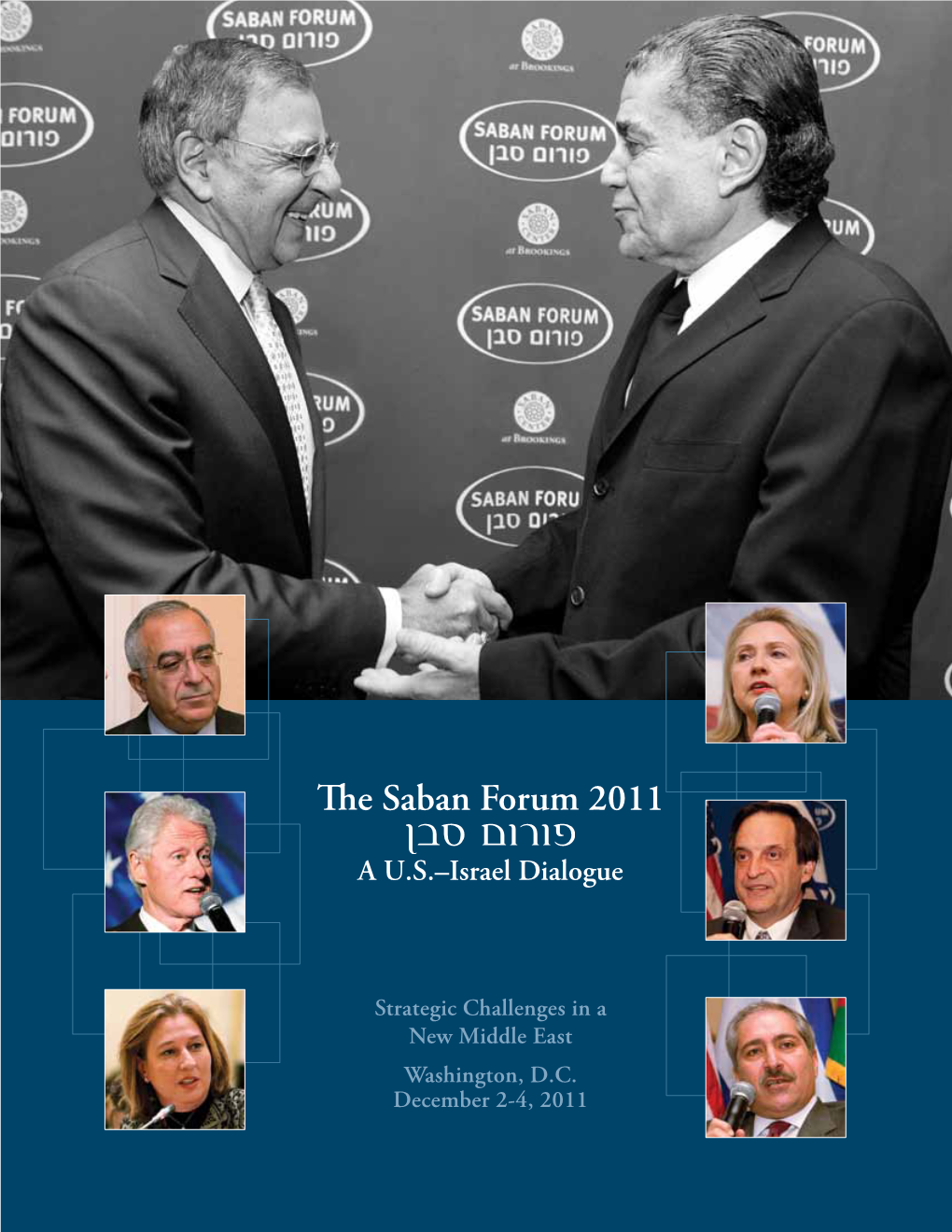

The Saban Forum 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Additional Documents to the Amicus Brief Submitted to the Jerusalem District Court

בבית המשפט המחוזי בירושלים עת"מ 36759-05-18 בשבתו כבית משפט לעניינים מנהליים בעניין שבין: 1( ארגון Human Rights Watch 2( עומר שאקר העותרים באמצעות עו"ד מיכאל ספרד ו/או אמילי שפר עומר-מן ו/או סופיה ברודסקי מרח' דוד חכמי 12, תל אביב 6777812 טל: 03-6206947/8/9, פקס 03-6206950 - נ ג ד - שר הפנים המשיב באמצעות ב"כ, מפרקליטות מחוז ירושלים, רחוב מח"ל 7, מעלות דפנה, ירושלים ת.ד. 49333 ירושלים 9149301 טל: 02-5419555, פקס: 026468053 המכון לחקר ארגונים לא ממשלתיים )עמותה רשומה 58-0465508( ידיד בית המשפט באמצעות ב"כ עו"ד מוריס הירש מרח' יד חרוצים 10, ירושלים טל: 02-566-1020 פקס: 077-511-7030 השלמת מסמכים מטעם ידיד בית המשפט בהמשך לדיון שהתקיים ביום 11 במרץ 2019, ובהתאם להחלטת כב' בית המשפט, מתכבד ידיד בית המשפט להגיש את ריכוז הציוציו של העותר מס' 2 החל מיום 25 ליוני 2018 ועד ליום 10 למרץ 2019. כפי שניתן להבחין בנקל מהתמצית המצ"ב כנספח 1, בתקופה האמורה, אל אף טענתו שהינו "פעיל זכויות אדם", בפועל ציוציו )וציוציו מחדש Retweets( התמקדו בנושאים שבהם הביע תמיכה בתנועת החרם או ביקורת כלפי מדינת ישראל ומדיניותה, אך נמנע, כמעט לחלוטין, מלגנות פגיעות בזכיות אדם של אזרחי מדינת ישראל, ובכלל זה, גינוי כלשהו ביחס למעשי רצח של אזרחים ישראלים בידי רוצחים פלסטינים. באשר לטענתו של העותר מס' 2 שחשבון הטוויטר שלו הינו, בפועל, חשבון של העותר מס' 1, הרי שגם כאן ניתן להבין בנקל שטענה זו חסרת בסיס כלשהי. ראשית, החשבון מפנה לתפקידו הקודם בארגון CCR, אליו התייחסנו בחוות הדעת המקורית מטעם ידיד בית המשפט בסעיף 51. -

Governments of Israel

Governments of Israel Seventeenth Knesset: Government 31 Government 31 Government 31 To Government 31 - Current Members 04/05/2006 Ministers Faction** Prime Minister Ehud Olmert 04/05/2006 Kadima Vice Prime Minister Shimon Peres 04/05/2006- 13/06/2007 Kadima Haim Ramon 04/07/2007 Kadima Acting Prime Minister Tzipi Livni 04/05/2006 Kadima Deputy Prime Minister Shaul Mofaz 04/05/2006 Kadima Eliyahu Yishai 04/05/2006 Shas Labor- Amir Peretz 04/05/2006- 18/06/2007 Meimad Yisrael Avigdor Liberman 30/10/2006- 18/01/2008 Beitenu Ehud Barak 18/06/2007 Labor- Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development Shalom Simhon 04/05/2006 Meimad Minister of Communications Ariel Atias 04/05/2006 Shas Labor- Minister of Defense Amir Peretz 04/05/2006- 18/06/2007 Meimad Ehud Barak 18/06/2007 Labor- Minister of Education Yuli Tamir 04/05/2006 Meimad Minister of Environmental Protection Gideon Ezra 04/05/2006 Kadima Minister of Finance Abraham Hirchson 04/05/2006- 03/07/2007 Kadima Ronnie Bar-On 04/07/2007 Kadima Minister of Foreign Affairs Tzipi Livni 04/05/2006 Kadima Gil Minister of Health Yacov Ben Yizri 04/05/2006 Pensioners Party Minister of Housing and Construction Meir Sheetrit 04/05/2006- 04/07/2007 Kadima Ze`ev Boim 04/07/2007 Kadima Minister of Immigrant Absorption Ze`ev Boim 04/05/2006- 04/07/2007 Kadima Jacob Edery 04/07/2007- 14/07/2008 Kadima Eli Aflalo 14/07/2008 Kadima Minister of Industry, Trade, and Labor Eliyahu Yishai 04/05/2006 Shas Minister of Internal Affairs Ronnie Bar-On 04/05/2006- 04/07/2007 Kadima Meir Sheetrit 04/07/2007 Kadima -

The Lost Decade of the Israeli Peace Camp

The Lost Decade of the Israeli Peace Camp By Ksenia Svetlova Now that Israeli annexation of Jewish settlements in the West Bank is a commonplace notion, it seems almost impossible that just twelve years ago, Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA) were making significant progress in the US-sponsored bilateral peace negotiations. Since then, the stalemate in the talks has become the new normal, under three consecutive governments headed by Benjamin Netanyahu. The Palestinians, led by Mahmoud Abbas and his government, have been cast as “diplomatic terrorists” for asking the international community for help. The Israeli peace camp has been subjected to a vicious smear campaign that has shaken its self-esteem and ruined its chances of winning over the public. This systematic smearing of Israeli and Palestinian two-staters has paid off. In the April 2019 elections, Israel’s progressive Meretz party teetered on the edge of the electoral barrier while Labor, once the ruling party, gained only six mandates (5% of the votes). The centrist Blue and White, a party led by ex-army chief Benny Gantz, carefully avoided any mention of loaded terms such as “the two-state solution” or “evacuation of settlements”, only calling vaguely to “advance peace” – as part of Israel’s new political vocabulary, which no longer includes “occupation” or even “the West Bank”. Despite offering no clear alternative to the peace option it managed to successfully derail, the Israeli right under Netanyahu has been in power for over a decade in a row, since 2009. Israel’s left-wing parties are fighting to survive; the Palestinians are continuing their fruitless efforts to engage the international community; and the horrid reality of a single state, in which different groups have different political and civil rights, seems just around the corner. -

How Palestinians Can Burst Israel's Political Bubble

Al-Shabaka Policy Brief Policy Al-Shabaka March 2018 WHEN LEFT IS RIGHT: HOW PALESTINIANS CAN BURST ISRAEL’S POLITICAL BUBBLE By Amjad Iraqi Overview the allies holding up his fragile rule, from the ultra- orthodox Jewish parties to his personal rivals within Although no indictments have been issued yet, Israelis Likud. “King Bibi,” however, survived them all. A are speculating whether the latest developments in skilled politician, he has been adept at managing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s corruption Israel’s notoriously volatile coalition system, and [email protected] scandals finally mark the beginning of his political has remained in power with three consecutive demise. The second-longest serving prime minister governments over nine years – each more right wing after David Ben-Gurion, Netanyahu has had a than the last.2 profound impact on Israel’s political scene since the 1990s. It is therefore troubling, especially to Netanyahu directly influenced the country’s media Palestinians, that if these corruption cases are the landscape by shaping the editorial stance of Israel harbinger of Netanyahu’s downfall, they will have Hayom (the nation’s gratis, most-read newspaper, had nothing to do with the more egregious crimes for funded by American billionaire Sheldon Adelson), which he is responsible, and for which he – and future and used the Communications Ministry to threaten Israeli leaders – have yet to be held accountable. and harass media outlets that were critical of him. Despite crises and condemnations throughout This policy brief analyzes Israel’s political his career – including mass Israeli protests for transformations under Netanyahu and maps out the socioeconomic justice in 2011 and, more recently, current leadership contenders from a Palestinian weekly protests against widespread government perspective.1 It argues that Israel’s insular political corruption – Netanyahu withstood public pressures discourse, and the increasing alignment of Israeli to step down. -

Netanyahu Incita All’

Israele guarda con nervosismo come Trump abbandoni i suoi alleati siriani Lily Galili – Tel Aviv, Israele 10 ottobre 2019 – Middle East Eye Negli ultimi giorni la leadership israeliana ha imparato due cose: a non credere di sapere cosa farà il presidente USA e a non fidarsi di lui come alleato. Durante il Capodanno ebraico è successa una cosa incredibile: per la prima volta il presidente Trump è stato paragonato, nei media israeliani, al suo predecessore, Barack Obama. Non è cosa di poco conto. Per la maggioranza degli israeliani, che si colloca fra il centro e l’estrema destra, Trump è un idolo americano, il migliore amico che Israele abbia mai avuto alla Casa Bianca. Barack Hussein Obama era, per quegli stessi israeliani, l’epitome di tutti i mali. Secondo il Pew, un centro di ricerca con sede a Washington, uno studio recente ha rilevato che solo 2 Paesi su 37 preferiscono Trump a Obama: Russia e Israele. E probabilmente è ancora così. Ma il senso di preoccupazione e di tradimento incombente, innescato dal ritiro improvviso delle truppe americane dal nord della Siria e dall’abbandono senza scrupoli dei curdi, alleati sia dell’America che di Israele, ora cancella l’iniziale adorazione. Né i militari né i politici israeliani considerano la riduzione delle truppe Usa e l’offensiva militare turca che ne è seguita come un pericolo imminente per Israele. Finora ‘i disordini’, come le fonti ufficiali tendono a descrivere la situazione, sono confinati a una regione lontana dal confine tra Israele e la Siria. Ci sono comunque due elementi che preoccupano notevolmente Israele. -

Command and Control | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Command and Control by David Makovsky, Olivia Holt-Ivry May 23, 2012 ABOUT THE AUTHORS David Makovsky David Makovsky is the Ziegler distinguished fellow at The Washington Institute and director of the Koret Project on Arab-Israel Relations. Olivia Holt-Ivry Articles & Testimony his week, the world's major powers resumed negotiations with Iran over its nuclear program. Should they fail, T the specter of a possible Israeli strike looms large, seeming to grow more likely as Tehran's nuclear program advances. In recent weeks, however, the conventional wisdom has shifted to favor the view that Israel is not on the cusp of a strike against Iran. This has been driven in part by public comments from former Israeli security officials -- notably former Mossad head Meir Dagan and former Shin Bet head Yuval Diskin -- questioning the wisdom of such an attack. An Israeli strike is not feasible, the thinking goes, so long as its security community remains divided -- and the thinly veiled threats of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Ehud Barak are therefore mere bluster. Don't be so sure. Dagan and Diskin's views aren't likely to tell us much about the likelihood of a strike on Iran one way or the other. For starters, they're former officials -- given the sensitivity of this issue, and the recent media misinterpretation of Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Chief of Staff Benny Gantz's remarks earlier this month, no other current members of the security establishment are likely to go public with their views. -

Sponsored by Event Partner

Sponsored by Event Partner: 1 Contents Agenda .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Sponsored by: Welcome from Sir Trevor Chinn, CVO ........................................................................................................... 6 Welcome from Hugo Bieber ..............................................................................................................................7 Speaker biographies Keynote Speaker - Ambassador Dan Gillerman ................................................................................. 8 Keynote Speaker - Sir Ronald Cohen .................................................................................................... 9 Event Partner: Panel: Israeli Investment Opportunity Landscape ............................................................................ 10 Panel: UK Investor Perspectives ............................................................................................................ 12 Private Equity Opportunities In Israel ........................................................................................................... 14 The Concentration Law .................................................................................................................................... 16 Israeli Private Equity Funds ranked by Capital Raised 1996-2013 ..........................................................24 Organised by: 3 Agenda 08:30 – -

The Forgotten Story of the Mizrachi Jews: Will the Jews of the Middle East Ever Be Compensated for Their Expulsion from the Arab World?

Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal Volume 23 Article 4 9-1-2004 The Forgotten Story of the Mizrachi Jews: Will the Jews of the Middle East Ever Be Compensated for Their Expulsion from the Arab World? Joseph D. Zargari Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph D. Zargari, The Forgotten Story of the Mizrachi Jews: Will the Jews of the Middle East Ever Be Compensated for Their Expulsion from the Arab World?, 23 Buff. Envtl. L.J. 157 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj/vol23/iss1/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORGOTTEN STORY OF THE MIZRA CHI JEWS: WILL THE JEWS OF THE MIDDLE EAST EVER BE COMPENSATED FOR THEIR EXPULSION FROM THE ARAB WORLD? Joseph D. Zargarit Introduction When people think of the refugee situation in the Middle East, they often think of the Palestinian refugees of the West Bank and Gaza. Their situation has been studied, written about, and debated throughout much of the world. What is often forgotten, however, is the story of another group of refugees in the Middle East that were displaced around the same time as the Palestinian refugees. -

“Schlaglicht Israel”!

Schlaglicht Israel Nr. 3/17 Aktuelles aus israelischen Tageszeitungen 1.-15. Februar Die Themen dieser Ausgabe Netanyahu bei Trump ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Räumung von Amona und umstrittenes Reglementierungsgesetz ........................................................................... 4 Wieder Krieg im Gazastreifen? ................................................................................................................................. 6 Medienquerschnitt .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Netanyahu bei Trump ness. He clearly sees who the Middle East good Im Vorfeld der Reise von Regierungschef Benjamin guys and bad guys are. (…) The meeting between Netanyahu nach Washington, dämpfte der neue US- Netanyahu and Trump will put a lock on the past Präsident Donald Trump die Erwartungen in Israel. eight years and usher in a new chapter in the history In einem exklusiven Interview mit der Tageszeitung of our region. (…) The time has come to put pres- Israel Hayom erklärte Trump, dass ein Umzug der sure on these who really sow murder and put world Botschaft von Tel Aviv nach Jerusalem, wie er ihn peace at risk: the various Islamic terrorist organiza- zuvor in Aussicht gestellt hatte, „wohl überlegt“ sein tions, from Hamas to Hezbollah, and dark regimes müsse. Auch bei Israels Bau von Wohnungen für -

CA 6821/93 Bank Mizrahi V. Migdal Cooperative Village 1

CA 6821/93 Bank Mizrahi v. Migdal Cooperative Village 1 CA 6821/93 LCA 1908/94 LCA 3363/94 United Mizrahi Bank Ltd. v. 1. Migdal Cooperative Village 2. Bostan HaGalil Cooperative Village 3. Hadar Am Cooperative Village Ltd 4. El-Al Agricultural Association Ltd. CA 6821/93 1. Givat Yoav Workers Village for Cooperative Agricultural Settlement Ltd 2. Ehud Aharonov 3. Aryeh Ohad 4. Avraham Gur 5. Amiram Yifhar 6. Zvi Yitzchaki 7. Simana Amram 8. Ilan Sela 9. Ron Razon 10. David Mini v. 1. Commercial Credit Services (Israel) Ltd 2. The Attorney General LCA 1908/94 1. Dalia Nahmias 2. Menachem Nahmias v. Kfar Bialik Cooperative Village Ltd LCA 3363/94 The Supreme Court Sitting as the Court of Civil Appeals [November 9, 1995] Before: Former Court President M. Shamgar, Court President A. Barak, Justices D. Levine, G. Bach, A. Goldberg, E. Mazza, M. Cheshin, Y. Zamir, Tz. E Tal Appeal before the Supreme Court sitting as the Court of Civil Appeals 2 Israel Law Reports [1995] IsrLR 1 Appeal against decision of the Tel-Aviv District Court (Registrar H. Shtein) on 1.11.93 in application 3459/92,3655, 4071, 1630/93 (C.F 1744/91) and applications for leave for appeal against the decision of the Tel-Aviv District Court (Registrar H. Shtein) dated 6.3.94 in application 5025/92 (C.F. 2252/91), and against the decision of the Haifa District Court (Judge S. Gobraan), dated 30.5.94 in application for leave for appeal 18/94, in which the appeal against the decision of the Head of the Execution Office in Haifa was rejected in Ex.File 14337-97-8-02. -

Israeli Election Bulletin | January 15

Israeli Election Bulletin | January 15 On 23 December 2020 the Knesset was automatically dissolved after the national unity government failed to pass a 2020 state budget. The election will be held on 23 March 2021. For more background on the collapse of the coalition, watch BICOM Director Richard Pater and read this BICOM Morning Brief. BICOM's Poll of Polls Aggregate Polling January 5-15 Many parties such as Momentum, Labour, Veterans, New Economy and Telem are polling under the electoral threshold Two others, Blue and White and Religious Zionism, are polling very close to the threshold (4 seats). If either of them were to fall under it, it would signicantly aect the ability of Netanyahu or his opponents to form a coalition 1/11 Splits, Mergers and Acquisitions We are now in the rst stage of the election process. Over the coming three weeks, politicians will start jockeying for their places ahead of the formation of the party lists that need to be submitted by 4 February. Party size and where they stand on major political issues Political Cartoons Maariv 23.12.20 Santa delvers ballot boxes and 21.12.20 Yediot Ahronot The new mutation. A two headed Gideon Saar and Naftali Bennett chase Gantz and Netanyahu Israel Hayom 24.12.20 “The clothes have no emperor,” the briefcase says Blue and White, looking on former number 2 and 3 in the party. Justice Minister Avi Nissenkorn who quit shortly after the government fell to join the Ron Huldai’s the Israelis Party and Foreign Minister Gabi Ashkenazi who will see out his role but not stand in the coming election. -

Operation Cast Lead--Zion Fascism at Its Best

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 29, No.2, July - December 2014, pp. 685-694 Operation Cast Lead--Zion Fascism at Its Best Umbreen Javaid University of Punjab, Lahore. Maliha Shamim University of Punjab, Lahore. Abstract Jews consider themselves to be the original inhabitants of Palestine. It has always been the official policy of Israel to occupy and populate the Palestinian territories. The victories in successive Arab-Israeli wars emboldened Israel to pursue its policy more vigorously. The Palestinians of occupied territories specially those living in West Bank and Gaza have to face the onslaught of Israeli atrocities. After breaking the truce entered into with Hamas, Israel attacked Gaza in December 2008, justifying the attacks as its right of self-defense. The Gazan operation named Operation Lead was not condemned by EU, US or European countries. To prepare the Israeli army for the Gaza offensive the troops were even religiously and politically brainwashed to successfully combat the Palestinians. The elections held after the Gaza offensive and extremist candidates returned to the Israeli parliament. Such extremist stance taken by Israeli public will go a long way in making the already biased Israeli society a more racist and fascist Israeli polity. In the absence of any criticism or condemnation of Israeli actions it pursues the murder and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians with impunity. Accumulation of latest weaponry and warring techniques have transformed Israel into a regional Sparta and religious extremism and fascism have come to assume an important place in today’s Israel. This article has been prepared with the help of newspapers and answers certain questions as why is Palestine most coveted by Jews.