Craft History of the KY Guard 1937 – 1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petrology, Sedimentology, and Diagenesis of Hemipelagic Limestone and Tuffaeeous Turbidites in the Aksitero Formation, Central Luzon, Philippines

Petrology, Sedimentology, and Diagenesis of Hemipelagic Limestone and Tuffaeeous Turbidites in the Aksitero Formation, Central Luzon, Philippines Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Mines, Republic of the Philippines, and the U.S. National Science Foundation Petrology, Sedimentology, and Diagenesis of Hemipelagic Limestone and Tuffaceous Turbidites in the Aksitero Formation, Central Luzon, Philippines By ROBERT E. GARRISON, ERNESTO ESPIRITU, LAWRENCE J. HORAN, and LAWRENCE E. MACK GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1112 Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Mines, Republic of the Philippines, and the U.S. National Science Foundation UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1979 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director United States. Geological Survey. Petrology, sedimentology, and diagenesis of hemipelagic limestone and tuffaceous turbidites in the Aksitero Formation, central Luzon, Philippines. (Geological Survey Professional Paper; 1112) Bibliography: p. 15-16 Supt. of Docs. No.: 119.16:1112 1. Limestone-Philippine Islands-Luzon. 2. Turbidites-Philippine Islands-Luzon. 3. Geology, Stratigraphic-Eocene. 4. Geology, Stratigraphic-Oligocene. 5. Geology-Philippine Islands- Luzon. I. Garrison, Robert E. II. United States. Bureau of Mines. III. Philippines (Republic) IV. United States. National Science Foundation. V. Title. VI. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional Paper; 1112. QE471.15.L5U54 1979 552'.5 79-607993 For sale -

Always Ready, Always There

ALWAYS READY, ALWAYS THERE Citizen Soldiers respond to EF3 tornado in their own community 8 AIRMEN BLAZE TRAIL at BWC 14 | GUARDSMAN VOICE OF HOPE 10 FEATURES 10 12-13 14-16 18 Voice of Hope Soldiers & Airmen Join Forces Best Warriors Compete Fitness Goals Mississippi Army Nation- Soldiers and Airmen of Mississippi Army and Health and Fitness are al Guard Sgt. 1st Class Mississippi National Guard Air National Guardsmen crucial to the readiness of Stephanie Kennett is named disaster response units train compete for the title of today’s military forces. 1st the 2017 National Guard with local and state agencies Soldier of the Year and Sgt. John Melson shares Sexual Assault Response to learn to respond to threats Non-commissioned Officer workout tips to improve your Coordinator. from weapons of mass de- of the Year during the 2017 fitness routine and reach struction. Best Warrior Competition at your goals. Camp McCain. The Guard Detail is the official magazine of the Mississippi National Guard. It is published three times a year with a circulation of 12,300 copies and is distributed online via the Mississippi National Guard web and Facebook pages. Opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the Army, Air Force, Army National Guard, Air National Guard or the Department of Defense. Editorial content is edited, prepared and provided by the Office of Public Affairs, Joint Force Headquarters, Mississippi, State of Mississippi Military Department. All photographs and graphic devices are copyrighted to the State of Mississippi, Military Department unless otherwise indicated. All submissions should pertain to the Mississippi National Guard and are subject to editing. -

Part Ii Metro Manila and Its 200Km Radius Sphere

PART II METRO MANILA AND ITS 200KM RADIUS SPHERE CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA 7.1 PHYSICAL PROFILE The area defined by a sphere of 200 km radius from Metro Manila is bordered on the northern part by portions of Region I and II, and for its greater part, by Region III. Region III, also known as the reconfigured Central Luzon Region due to the inclusion of the province of Aurora, has the largest contiguous lowland area in the country. Its total land area of 1.8 million hectares is 6.1 percent of the total land area in the country. Of all the regions in the country, it is closest to Metro Manila. The southern part of the sphere is bound by the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon, all of which comprise Region IV-A, also known as CALABARZON. 7.1.1 Geomorphological Units The prevailing landforms in Central Luzon can be described as a large basin surrounded by mountain ranges on three sides. On its northern boundary, the Caraballo and Sierra Madre mountain ranges separate it from the provinces of Pangasinan and Nueva Vizcaya. In the eastern section, the Sierra Madre mountain range traverses the length of Aurora, Nueva Ecija and Bulacan. The Zambales mountains separates the central plains from the urban areas of Zambales at the western side. The region’s major drainage networks discharge to Lingayen Gulf in the northwest, Manila Bay in the south, the Pacific Ocean in the east, and the China Sea in the west. -

War Crimes in the Philippines During WWII Cecilia Gaerlan

War Crimes in the Philippines during WWII Cecilia Gaerlan When one talks about war crimes in the Pacific, the Rape of Nanking instantly comes to mind.Although Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War, it did not ratify it, partly due to the political turmoil going on in Japan during that time period.1 The massacre of prisoners-of-war and civilians took place all over countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army long before the outbreak of WWII using the same methodology of terror and bestiality. The war crimes during WWII in the Philippines described in this paper include those that occurred during the administration of General Masaharu Homma (December 22, 1941, to August 1942) and General Tomoyuki Yamashita (October 8, 1944, to September 3, 1945). Both commanders were executed in the Philippines in 1946. Origins of Methodology After the inauguration of the state of Manchukuo (Manchuria) on March 9, 1932, steps were made to counter the resistance by the Chinese Volunteer Armies that were active in areas around Mukden, Haisheng, and Yingkow.2 After fighting broke in Mukden on August 8, 1932, Imperial Japanese Army Vice Minister of War General Kumiaki Koiso (later convicted as a war criminal) was appointed Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army (previously Chief of Military Affairs Bureau from January 8, 1930, to February 29, 1932).3 Shortly thereafter, General Koiso issued a directive on the treatment of Chinese troops as well as inhabitants of cities and towns in retaliation for actual or supposed aid rendered to Chinese troops.4 This directive came under the plan for the economic “Co-existence and co-prosperity” of Japan and Manchukuo.5 The two countries would form one economic bloc. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Department of Defense Office of the Secretary

Monday, May 16, 2005 Part LXII Department of Defense Office of the Secretary Base Closures and Realignments (BRAC); Notice VerDate jul<14>2003 10:07 May 13, 2005 Jkt 205001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\16MYN2.SGM 16MYN2 28030 Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 93 / Monday, May 16, 2005 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE Headquarters U.S. Army Forces Budget/Funding, Contracting, Command (FORSCOM), and the Cataloging, Requisition Processing, Office of the Secretary Headquarters U.S. Army Reserve Customer Services, Item Management, Command (USARC) to Pope Air Force Stock Control, Weapon System Base Closures and Realignments Base, NC. Relocate the Headquarters 3rd Secondary Item Support, Requirements (BRAC) U.S. Army to Shaw Air Force Base, SC. Determination, Integrated Materiel AGENCY: Department of Defense. Relocate the Installation Management Management Technical Support ACTION: Notice of Recommended Base Agency Southeastern Region Inventory Control Point functions for Closures and Realignments. Headquarters and the U.S. Army Consumable Items to Defense Supply Network Enterprise Technology Center Columbus, OH, and reestablish SUMMARY: The Secretary of Defense is Command (NETCOM) Southeastern them as Defense Logistics Agency authorized to recommend military Region Headquarters to Fort Eustis, VA. Inventory Control Point functions; installations inside the United States for Relocate the Army Contracting Agency relocate the procurement management closure and realignment in accordance Southern Region Headquarters to Fort and related support functions for Depot with Section 2914(a) of the Defense Base Sam Houston. Level Reparables to Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD, and designate them as Closure and Realignment Act of 1990, as Operational Army (IGPBS) amended (Pub. -

Military Institutions and Activities, 1850-1980

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities, 1850-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources November 2019 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Related Contexts and Evaluation Considerations 1 Other Sources for Military Historic Contexts 3 MILITARY INSTITUTIONS AND ACTIVITIES HISTORIC CONTEXT 3 Historical Overview 3 Los Angeles: Mexican Era Settlement to the Civil War 3 Los Angeles Harbor and Coastal Defense Fortifications 4 The Defense Industry in Los Angeles: From World War I to the Cold War 5 World War II and Japanese Forced Removal and Incarceration 8 Recruitment Stations and Military/Veterans Support Services 16 Hollywood: 1930s to the Cold War Era 18 ELIGIBILITY STANDARDS FOR AIR RAID SIRENS 20 ATTACHMENT A: FALLOUT SHELTER LOCATIONS IN LOS ANGELES 1 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities PREFACE These “Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities” (Guidelines) were developed based on several factors. First, the majority of the themes and property types significant in military history in Los Angeles are covered under other contexts and themes of the citywide historic context statement as indicated in the “Introduction” below. Second, many of the city’s military resources are already designated City Historic-Cultural Monuments and/or are listed in the National Register.1 Finally, with the exception of air raid sirens, a small number of military-related resources were identified as part of SurveyLA and, as such, did not merit development of full narrative themes and eligibility standards. -

Hall's Manila Bibliography

05 July 2015 THE RODERICK HALL COLLECTION OF BOOKS ON MANILA AND THE PHILIPPINES DURING WORLD WAR II IN MEMORY OF ANGELINA RICO de McMICKING, CONSUELO McMICKING HALL, LT. ALFRED L. McMICKING AND HELEN McMICKING, EXECUTED IN MANILA, JANUARY 1945 The focus of this collection is personal experiences, both civilian and military, within the Philippines during the Japanese occupation. ABAÑO, O.P., Rev. Fr. Isidro : Executive Editor Title: FEBRUARY 3, 1945: UST IN RETROSPECT A booklet commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of the University of Santo Tomas. ABAYA, Hernando J : Author Title: BETRAYAL IN THE PHILIPPINES Published by: A.A. Wyn, Inc. New York 1946 Mr. Abaya lived through the Japanese occupation and participated in many of the underground struggles he describes. A former confidential secretary in the office of the late President Quezon, he worked as a reporter and editor for numerous magazines and newspapers in the Philippines. Here he carefully documents collaborationist charges against President Roxas and others who joined the Japanese puppet government. ABELLANA, Jovito : Author Title: MY MOMENTS OF WAR TO REMEMBER BY Published by: University of San Carlos Press, Cebu, 2011 ISBN #: 978-971-539-019-4 Personal memoir of the Governor of Cebu during WWII, written during and just after the war but not published until 2011; a candid story about the treatment of prisoners in Cebu by the Kempei Tai. Many were arrested as a result of collaborators who are named but escaped punishment in the post war amnesty. ABRAHAM, Abie : Author Title: GHOST OF BATAAN SPEAKS Published by: Beaver Pond Publishing, PA 16125, 1971 This is a first-hand account of the disastrous events that took place from December 7, 1941 until the author returned to the US in 1947. -

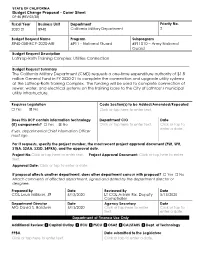

Lathrop-Roth Training Complex: Utilities Connection

STATE OF CALIFORNIA Budget Change Proposal - Cover Sheet DF-46 (REV 02/20) Fiscal Year Business Unit Department Priority No. 2020-21 8940 California Military Department 2 Budget Request Name Program Subprogram 8940-058-BCP-2020-MR 6911 - National Guard 6911010 – Army National Guard Budget Request Description Lathrop-Roth Training Complex: Utilities Connection Budget Request Summary The California Military Department (CMD) requests a one-time expenditure authority of $1.8 million General Fund in FY 2020-21 to complete the connection and upgrade utility systems at the Lathrop-Roth Training Complex. The funding will be used to complete connection of sewer, water, and electrical systems on the training base to the City of Lathrop’s municipal utility infrastructure. Requires Legislation Code Section(s) to be Added/Amended/Repealed ☐ Yes ☒ No Click or tap here to enter text. Does this BCP contain information technology Department CIO Date (IT) components? ☐ Yes ☒ No Click or tap here to enter text. Click or tap to enter a date. If yes, departmental Chief Information Officer must sign. For IT requests, specify the project number, the most recent project approval document (FSR, SPR, S1BA, S2AA, S3SD, S4PRA), and the approval date. Project No.Click or tap here to enter text. Project Approval Document: Click or tap here to enter text. Approval Date: Click or tap to enter a date. If proposal affects another department, does other department concur with proposal? ☐ Yes ☐ No Attach comments of affected department, signed and dated by the department director or designee. Prepared By Date Reviewed By Date COL Louis Millikan, J9 5/13/2020 LT COL Adam Rix, Deputy 5/13/2020 Comptroller Department Director Date Agency Secretary Date MG David S. -

The Bastards of Bataan: General Douglas Macarthur's Role

The Bastards of Bataan: General Douglas MacArthur’s Role in the Fall of the Philippines during World War II By: Lahia Marie Ellingson Senior Seminar: History 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University June 8, 2007 Readers Professor Kimberly Jensen Professor John L. Rector Copyright © Lahia Ellingson, 2007 On December 8, 1941, just hours after having attacked the United States’ fleet on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese army turned their attention toward another American stronghold, the forces stationed on the Philippines. Here the Japanese attacked Clark Field, an American airbase on the island of Luzon.1 The subsequent battle and surrender that ensued has become known as “…the worst defeat yet suffered by the United States, a source of national humiliation.”2 With all of the confusion and horror that happened to the men in the Philippines it is hard to understand where blame should be placed. Was it General Douglas MacArthur, the Commanding General in the Philippines at the time? Or were there other factors such as war in Europe and conflicting beliefs on how best to defend the Philippines that led to the defeat? Historians have debated MacArthur’s role in the Philippines for some time. There are those who believe that MacArthur should be held accountable for the fall of the Philippines and those who see him as a commanding general who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. In this paper it will be argued that MacArthur’s actions in the Philippines prior to his escape to Australia hastened the fall of the Philippines, which led to more death and brutality at the hands of the Japanese. -

French III, IV, XI Army Corps & I and II Cavalry Corps, Early October 1813

French III, IV, XI Army Corps & I and II Cavalry Corps Early October 1813 III Corps: Général de division Souham (5 October) 8th Division: Général de division Baron Brayer Brigade: Général de brigade Estève 2/,3/6th Légère Infantry Regiment 2/,3/16th Légère Infantry Regiment 1/,3/28th Légère Infantry Regiment 3/,4/40th Line Infantry Regiment Brigade: Général de brigade Baron Charrière 2/,3/59th Line Infantry Regiment 3/,4/69th Line Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,4/22nd Line Infantry Regiment Artillery: 10/2nd Foot Artillery 5/9th Foot Artillery Det. 3/9th Principal Train Battalion Det. 4/3rd (bis) Train Battalion 9th Division: Général de division Delmas Brigade: Général de brigade Anthing 2nd Provisional Légère Infantry Regiment 3/2nd Légère Infantry Regiment 3/4th Légère Infantry Regiment 3/,4/43rd Line Regiment 1/,2/,3/136th Line Infantry Regiment Brigade: Général de brigade Bergez de Bareaux 1/,2/,3/138th Line Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/145th Line Infantry Regiment Artillery: 2/9th Foot Artillery 11/9th Foot Artillery Det. 4/3rd (bis) Train Battalion Det. 4/6th Principal Train Battalion Det. 7/10th Principal Train Battalion 11th Division: Général de division Baron Ricard Brigade: Général de brigade van Dedem van de Gelder 3/,4/,6/9th Légère Infantry Regiment 2/,3/,4/50th Line Infantry Regiment 3/,4/65th Line Infantry Regiment (1 bn assigned to general artillery park) Brigade: Général de brigade Dumoulin 1/,2/,3/142nd Line Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/144th Line Infantry Regiment Artillery: 19/7th Foot Artillery 5/9th Foot Artillery Det. -

Kentucky Law Protects National Guard Members on State Active Duty

KY-2015-NG (Updated April 2018) Kentucky Law Protects National Guard Members On State Active Duty By Austin M. Giesel1 Under certain circumstances, members of the Army or Air National Guard can be called up for state active duty by the Governor of Kentucky or by another state governor. Kentucky law prohibits employment discrimination against members of the Kentucky National Guard2 or Kentucky active militia3 in Kentucky Revised Statutes (KRS) section 38.460 (1), which states: (1) No person shall, either by himself or with another, willfully deprive a member of the Kentucky National Guard or Kentucky active militia of his employment or prevent his being employed or in any way obstruct a member of the Kentucky National Guard or Kentucky active militia in the conduct of his trade, business, or profession or by threats of violence prevent any person from enlisting in the Kentucky National Guard or Kentucky active militia. Emphasis supplied. KRS section 38.238 provides further clarification of the employment rights by stating that: An employee shall be granted a leave of absence by his employer for the period required to perform active duty or training in the National Guard. Upon the employee's release from a period of active duty or training, he shall be permitted to return to his former position of employment with the seniority, status, pay or any other rights or benefits he would have had if he had not been absent, except that no employer shall be required to grant an employee a leave of absence with pay. This section provides for full reinstatement to a service member’s former position, akin to the protections provided by the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act (USERRA).4 1 Austin Giesel is one of two summer associates at the Service Members Law Center in the summer of 2014.