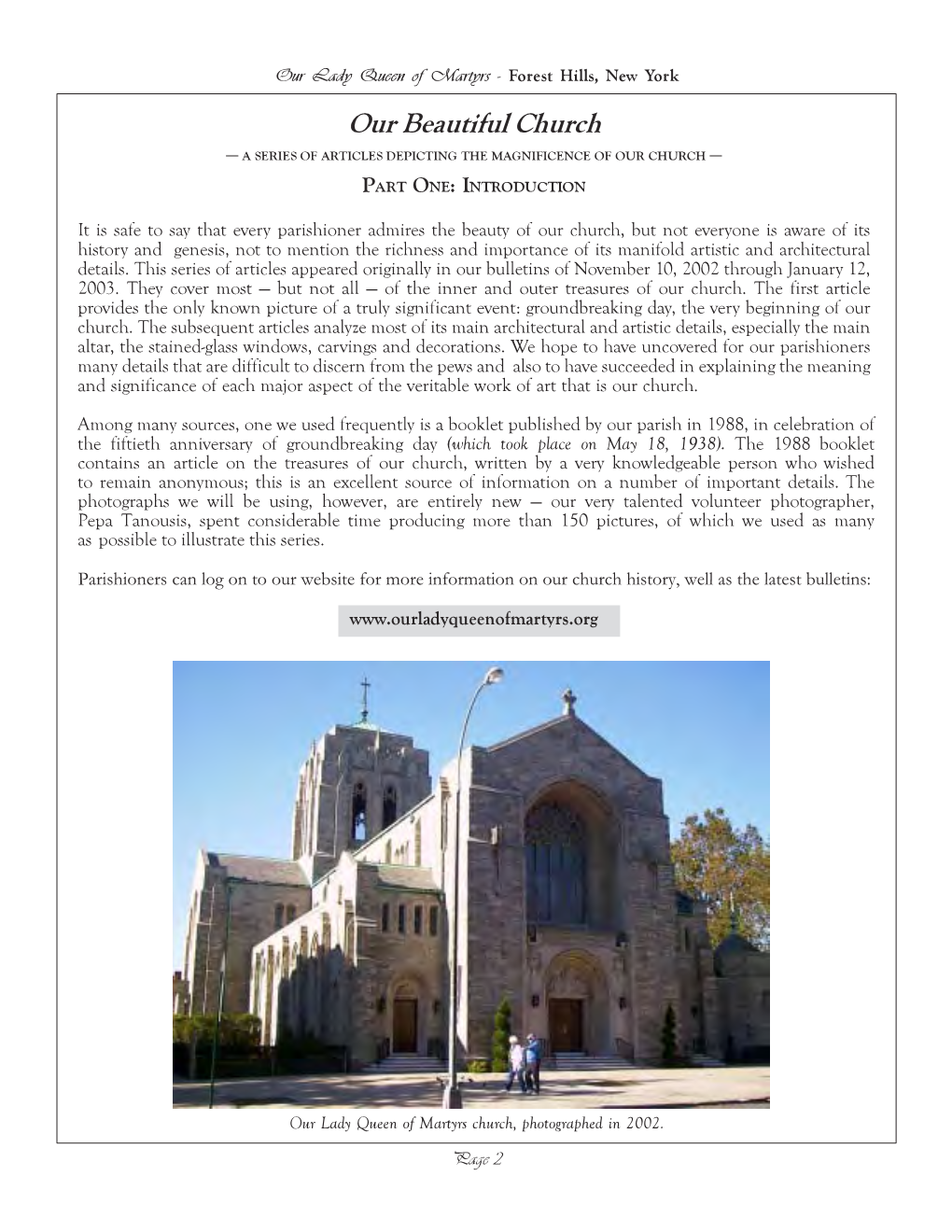

Our Beautiful Church — a SERIES of ARTICLES DEPICTING the MAGNIFICENCE of OUR CHURCH — PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic Example with a Plan That Resembles Romanesque

Gothic Art • The Gothic period dates from the 12th and 13th century. • The term Gothic was a negative term first used by historians because it was believed that the barbaric Goths were responsible for the style of this period. Gothic Architecture The Gothic period began with the construction of the choir at St. Denis by the Abbot Suger. • Pointed arch allowed for added height. • Ribbed vaulting added skeletal structure and allowed for the use of larger stained glass windows. • The exterior walls are no longer so thick and massive. Terms: • Pointed Arches • Ribbed Vaulting • Flying Buttresses • Rose Windows Video - Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and St. Denis Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic example with a plan that resembles Romanesque. • The interior goes from three to four levels. • The stone portals seem to jut forward from the façade. • Added stone pierced by arcades and arched and rose windows. • Filigree-like bell towers. Interior of Laon Cathedral, view facing east (begun c. 1190 CE). Exterior of Laon Cathedral, west facade (begun c. 1190 CE). Chartres Cathedral • Generally considered to be the first High Gothic church. • The three-part wall structure allowed for large clerestory and stained-glass windows. • New developments in the flying buttresses. • In the High Gothic period, there is a change from square to the new rectangular bay system. Khan Academy Video: Chartres West Facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Royal Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Nave, Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). -

Pages 114- 129 Great Architecture of the World Readings

Readings Pages 114- 129 Great Architecture of the World ARCH 1121 HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURAL TECHNOLOGY Photo: Alexander Aptekar © 2009 Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Influenced by Romanesque Architecture While Romanesque remained solid and massive – Gothic: 1) opened up to walls with enormous windows and 2) replaced semicircular arch with the pointed arch. Style emerged in France Support: Piers and Flying Buttresses Décor: Sculpture and stained glass Effect: Soaring, vertical and skeleton-like Inspiration: Heavenly light Goal: To lift our everyday life up to the heavens Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Dominant Art during this time was Architecture Growth of towns – more prosperous They wanted their own churches – Symbol of civic Pride More confident and optimistic Appreciation of Nature Church/Cathedral was the outlet for creativity Few people could read and write Clergy directed the operations of new churches- built by laymen Gothic Architecture 1140-1420 Began soon after the first Crusaders returned from Constantinople Brought new technology: Winches to hoist heavy stones New Translation of Euclid’s Elements – Geometry Gothic Architecture was the integration of Structure and Ornament – Interior Unity Elaborate Entrances covered with Sculpture and pronounced vertical emphasis, thin walls pierced by stained-glass Gothic Architecture Characteristics: Emphasis on verticality Skeletal Stone Structure Great Showing of Glass: Containers of light Sharply pointed Spires Clustered Columns Flying Buttresses Pointed Arches Ogive Shape Ribbed Vaults Inventive Sculpture Detail Sharply Pointed Spires Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Abbot Suger had the vision that started Gothic Architecture Enlargement due to crowded churches, and larger windows Imagined the interior without partitions, flowing free Used of the Pointed Arch and Rib Vault St. -

Circle Patterns in Gothic Architecture

Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Circle patterns in Gothic architecture Tiffany C. Inglis and Craig S. Kaplan David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science University of Waterloo [email protected] Abstract Inspired by Gothic-influenced architectural styles, we analyze some of the circle patterns found in rose windows and semi-circular arches. We introduce a recursive circular ring structure that can be represented using a set-like notation, and determine which structures satisfy a set of tangency requirements. To fill in the gaps between tangent circles, we add Appollonian circles to each triplet of pairwise tangent circles. These ring structures provide the underlying structure for many designs, including rose windows, Celtic knots and spirals, and Islamic star patterns. 1 Introduction Gothic architecture, a style of architecture seen in many great cathedrals and castles, developed in France in the late medieval period [1, 3]. This majestic style is often applied to ecclesiastical buildings to emphasize their grandeur and solemnity. Two key features of Gothic architecture are height and light. Gothic buildings are usually taller than they are wide, and the verticality is further emphasized through towers, pointed arches, and columns. In cathedrals, the walls are often lined with large stained glass windows to introduce light and colour into the buildings. In the mid-18th century, an architectural movement known as Gothic Revival began in England and quickly spread throughout Europe. The Neo-Manueline, or Portuguese Final Gothic, developed under the influence of traditional Gothic architecture and the Spanish Plateresque style [10]. The Palace Hotel of Bussaco, designed by Italian architect Luigi Manini and built between 1888 and 1907, is a well-known example of Neo-Manueline architecture (Figure 2). -

2-A-07-10-Not13-Instructions- Build a Cathedral-HS.Docx

ART 2-07 lnstructions to Build Your Cathedral 1. Print out all six pages on cardstock. 2. Cut out on all solid lines. Dotted lines are fold lines. 3. Page one: The Crossing. This should look familiar. We used it on the squinches and pendentive lesson. a. Cut down the center of the paper, to separate the pointed pieces (piece A) from the large piece (piece B) that has four folds. b. Take piece A and carefully cut all the dark areas away. Throw these dark pieces away. c. Glue section C under section D. C and D are parts of a point. When glued they make a whole point. d. Glue or tape the fold down areas of the dome. There are two ways to do this. i. First way: start on the C/D point and put a very tiny bit of glue on the back of the fold down section. Then bring point E over to the C/D point. C/D should be under the E point. Continue putting glue on the back of the glued down section and bringing the next point over. You may have overlap. That is okay. Just glue all the points to the center. ii. Second way: put tape on the inside of the C/D point and then bring all the points up and stick to the tape. e. The four triangles on the bottom of the dome are the squinches or pendentives. Fold them out. Carefully crease this fold. f. Set dome aside. Piece B is the nave. This is where the people sit. -

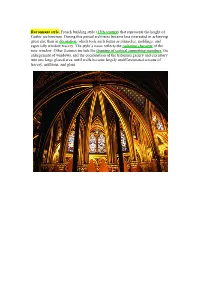

Rayonnant Style, French Building Style (13Th Century) That Represents the Height of Gothic Architecture

Rayonnant style, French building style (13th century) that represents the height of Gothic architecture. During this period architects became less interested in achieving great size than in decoration, which took such forms as pinnacles, moldings, and especially window tracery. The style’s name reflects the radiating character of the rose window. Other features include the thinning of vertical supporting members, the enlargement of windows, and the combination of the triforium gallery and clerestory into one large glazed area, until walls became largely undifferentiated screens of tracery, mullions, and glass. Flamboyant style, phase of late Gothic architecture in 15th-century France and Spain. It evolved out of the Rayonnant style’s increasing emphasis on decoration. Its most conspicuous feature is the dominance in stone window tracery of a flamelike S- shaped curve. Wall surface was reduced to the minimum to allow an almost continuous window expanse. Structural logic was obscured by covering buildings with elaborate tracery. Flamboyant Gothic, which became increasingly ornate, gave way in France to Renaissance forms in the 16th century. Perpendicular style, Phase of late Gothic architecture in England roughly parallel in time to the French Flamboyant style. The style, concerned with creating rich visual effects through decoration, was characterized by a predominance of vertical lines in stone window tracery, enlargement of windows to great proportions, and conversion of the interior stories into a single unified vertical expanse. Fan vaults, springing from slender columns or pendants, became popular. In the 16th century, the grafting of Renaissance elements onto the Perpendicular style resulted in the Tudor style. Manueline, Portuguese Manuelino, particularly rich and lavish style of architectural ornamentation indigenous to Portugal in the early 16th century. -

Rose Window Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Rose Window from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

6/19/2016 Rose window Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Rose window From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A rose window or Catherine window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The name “rose window” was not used before the 17th century and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other authorities, comes from the English flower name rose.[1] The term “wheel window” is often applied to a window divided by simple spokes radiating from a central boss or opening, while the term “rose window” is reserved for those windows, sometimes of a highly complex design, which can be seen to bear similarity to a multipetalled rose. Rose windows are also called Catherine windows after Saint Catherine of Alexandria who was sentenced to be executed on a spiked wheel. A circular Exterior of the rose at Strasbourg window without tracery such as are found in many Italian churches, is Cathedral, France. referred to as an ocular window or oculus. Rose windows are particularly characteristic of Gothic architecture and may be seen in all the major Gothic Cathedrals of Northern France. Their origins are much earlier and rose windows may be seen in various forms throughout the Medieval period. Their popularity was revived, with other medieval features, during the Gothic revival of the 19th century so that they are seen in Christian churches all over the world. Contents 1 History 1.1 Origin 1.2 The windows of Oviedo Interior of the rose at Strasbourg 1.3 Romanesque circular windows Cathedral. -

How the Windows of the Royal Chapel at St. Germain-En-Laye Reveal the History of This Powerful Site Meghan E

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design 5-7-2016 Uncovering the Past: How the Windows of the Royal Chapel at St. Germain-en-Laye Reveal the History of this Powerful Site Meghan E. Benesh Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Benesh, Meghan E., "Uncovering the Past: How the Windows of the Royal Chapel at St. Germain-en-Laye Reveal the History of this Powerful Site." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2016. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/198 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNCOVERING THE PAST: HOW THE WINDOWS OF THE ROYAL CHAPEL AT ST. GERMAIN-EN-LAYE REVEAL THE HISTORY OF THIS POWERFUL SITE by MEGHAN BENESH Under the Direction of John Decker, PhD ABSTRACT This essay focuses on the theological, social, and cultural contexts of the Royal Chapel at St. Germain-en-Laye. I pay particular attention to the rose window on the west wall, which was changed over time by the multiple renovations and redecorations by French monarchs as well as the “official restoration” in the 1880's. -

The Gothic Rose Window

COMPUTER-AIDED MODELING APPLIED TO ARCHITECTURAL KNOW-HOW: THE GOTHIC ROSE WINDOW SUBMITTED: August 2005 REVISED: November 2005 PUBLISHED: May 2006 at http://itcon.org/2006/26/ EDITOR: J. M. Kamara Nathalie Charbonneau, Ph.D. Candidate École d’Architecture, Faculté de l'Aménagement, Université de Montréal, (Québec) Canada email: [email protected] Dominic Boulerice, Ph.D. Candidate Department of Art History and Communication Studies, McGill University, Montréal, (Québec) Canada email: [email protected] David W. Booth, Associate Professor Département d’Histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques, Université de Montréal, (Québec) Canada email: [email protected] SUMMARY: This paper explains the parameters and methodology at the heart of an ongoing research project that seeks to verify whether one can trace back the genesis of any given artefact or work of art by means of computer-aided modeling. In its endeavour our Montréal-based research team aims to initiate and propose novel methods of modeling design processes. This approach is exemplified by a case study dealing with rose tracery designs adorning Gothic cathedrals of 12th and 13th Century Île-de-France. A computerized model re- enacting their design process was developed along with an interface enabling the translation of the designer’s intentions into a virtual design space. The stated goal of this research project is to evaluate empirically to what extent our modeling strategies can grasp a given artefact as a logical and articulate ensemble. Furthermore, we seek eventually to determine whether this kind of software programme would prove an indispensable tool in the development of the architectural designer’s cognitive abilities. -

From the Dome of Heaven to a Cupola in Space: Re-Engaging with Imagery and Symbolism Through 3D Digital Art Installations

From the dome of heaven to a cupola in space: Re-engaging with imagery and symbolism through 3D digital art installations Nick Lambert Department of History of Art and Screen Media, Birkbeck, University of London Vasari Research Centre, Birkbeck, 43 Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PD [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION as a kind of virtual window within a darkened space, and has been exhibited in both the USA and UK. This paper looks at the possibilities of re-engaging with imagery and symbolism from earlier cultures 2.1 Lux Nova , the ‘new light’ through the medium of 3D digital environments. It examines three of the author's digital artworks - Whilst researching the history of stained glass Oculus, Lux Nova and Music of the Spheres - as windows, the importance of Abbot Suger of St- vehicles for this process, and the means by which Denis abbey in medieval France became evident. this engagement with the past can also generate Suger encouraged the use of coloured glass in the new ideas within the area of art and technology. early Gothic churches, and created a theological The recreation of an architectural sense of space concept called “lux nova”, the new light. This and position is of particular importance, as is the indirectly inspired the projection Lux Nova , which development of particular approach to 3D software. moved back to a dome-based form and showed a succession of architectural spaces where changing 2. DEVELOPING ARTWORK FOR DOME light was a significant element of their spatial effect: PROJECTION the Neolithic tomb at Maes Howe, the Pantheon in Rome, the chancel of Notre Dame, Brunelleschi's The collaborative fulldome projection Music of the dome and the new Cupola installed in the Spheres served as a testing ground for the author's International Space Station. -

Conservation Strategy St Peter's Cathedral North Adelaide

CONSERVATION STRATEGY ST PETER'S CATHEDRAL NORTH ADELAIDE March 2014 McDougall & Vines Conservation and Heritage Consultants 27 Sydenham Road, Norwood, South Australia, 5067 Ph (08) 8362 6399 Fax (08) 8363 0121 Email: [email protected] CONSERVATION STRATEGY FOR ST PETER'S CATHEDRAL CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1.2 Objectives of Conservation Strategy Document 1.3 Existing Heritage Listings 1.4 Location of Site 1.5 Current Ownership and Management of the Cathedral 1.6 Acknowledgements 1.7 Authors of this Report 2.0 HISTORICAL OUTLINE AND ARCHITECTURAL ANALYSIS 5 2.1 Historical Development of St Peter’s Cathedral 2.1.1 Planning for the Cathedral 1847-1862 2.1.2 Stage One – 1869-1878 (Sanctuary, Choir, Transepts and One Bay of the Nave) 2.1.3 Stage Two – 1890-1894 Lower Section of Three Bays of the Nave 2.1.4 Stage Three – 1899-1901 Upper Section of Three Bays of the Nave 2.1.5 Stage Four – Towers & Spires 2.1.6 Stage Five – 1902-1904 Lady Chapel 2.1.7 Other Works 2.1.8 Setting 2.2 Architectural Description and Analysis 2.3 Walter Bagot’s Descriptions 1907-1945 2.4 Summary Time Line - Including Recent Works 2.5 Early Drawings of the Cathedral, Stages 1 – 5 2.6 Early Photographs of the Cathedral 3.0 STATEMENT OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF ST PETER'S CATHEDRAL 19 3.1 Cultural Significance 3.2 Delineation of Significant Fabric and Components 3.2.1 Site Elements 3.2.2 External Elements 3.2.3 Internal Elements 4.0 CURRENT CONDITION ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 21 4.1 Site Analysis and Recommendations 4.2 External Analysis -

Holy Name of Jesus Church – “Rose Window”

Holy Name of Jesus Church – “Rose Window” The term “rose window” (1) refers to the large, main stained glass window of a Church. It is designed to let in light and sometimes air into the worship space. Rose Window design varies from Church to Church based upon the architecture (Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic, etc.) and period built. Many are quite ornate in color, detail and imagery. They are generally based upon the denomination of the church, its namesake or devotion. They all seek to inspire. They usually appear either around the drum of a dome as at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Jerusalem), top of the dome of the Pantheon (Rome) or high in the end of a low- pitched gable as in Holy Name’s case. Holy Name of Jesus Roman Catholic Church’s Rose Window was built with the Church in 1878. It is of Gothic design. The window measures just under 10 feet high and just under 10 feet wide. The original window was a series of nine (9) separate glass panels in a wood frame in a “tic-tac-toe” pattern. The edge corners of the window host round panels flanked by square glass windows. The exterior of each panel was protected by an outer pane of glass. Holy Name’s Rose Window is themed for our Lord Jesus and specifically around parts of his Crucifixion. The panels in order depict (standing outside facing the Rose Window): • – The clubs and torches used by Jesus’s guards to beat and torment him on his way to Calvary.