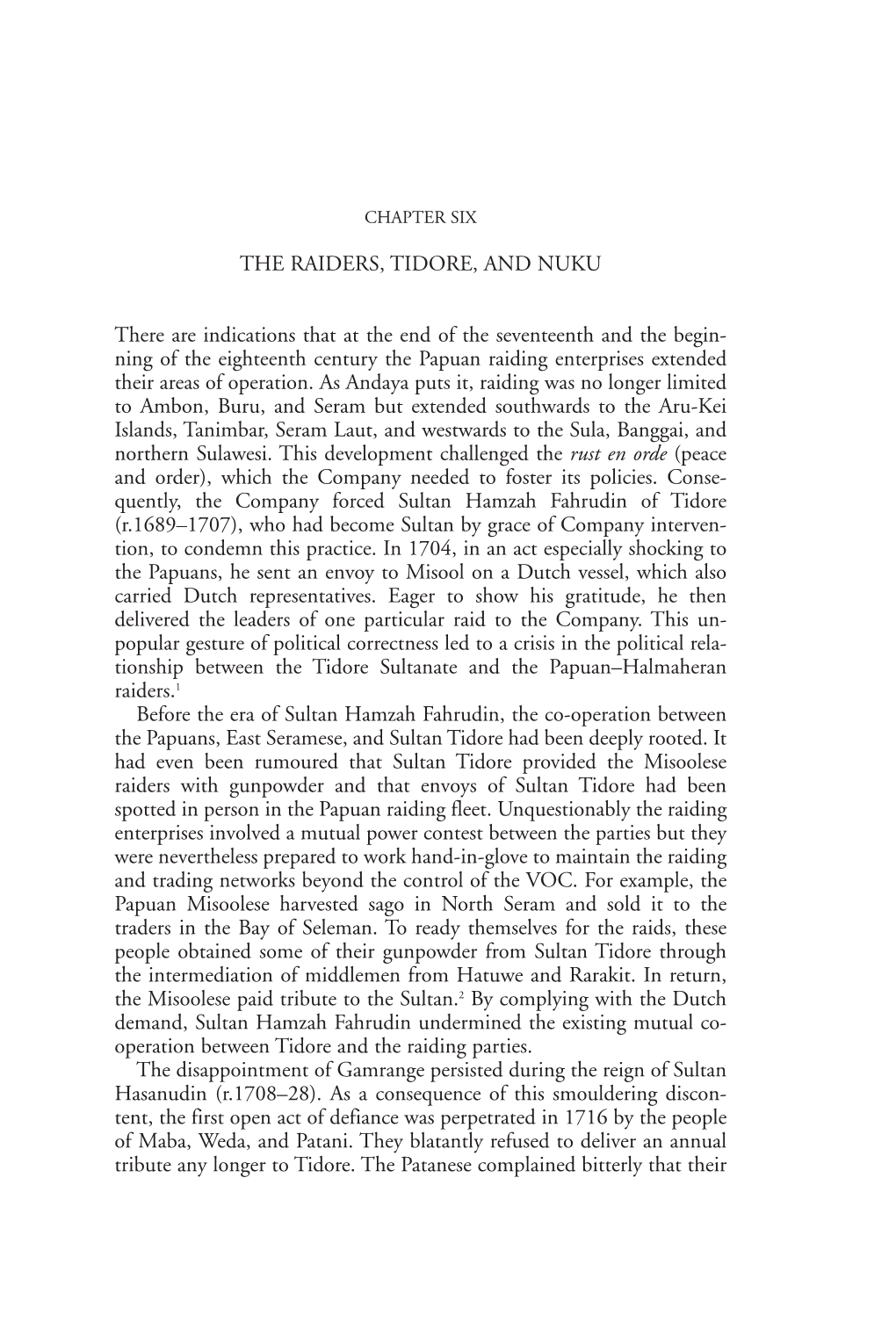

THE RAIDERS, TIDORE, and NUKU There Are Indications That At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Influence of Conflict on Migration at Moluccas Province

INFLUENCE OF CONFLICT ON MIGRATION AT MOLUCCAS PROVINCE Maryam Sangadji Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Pattimura Ambon Abstraksi Konflik antara komunitas islam dan Kristen di propinsi Maluku menyebabkan lebih dari sepertiga populasi penduduknya atau 2,1 juta orang menjadi IDP (pengungsi) serta mengalami kemiskinan dan penderitaan. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk meneliti proses, dampak dan masalah yang dihadapi para IDP. Hasil analisis kualitatif deskriptif menunjukkan bahwa proses migrasi IDP ditentukan oleh tingkat intensitas konflik dan lebih marginal pada lokasi IDP. Disamping itu terlampau banyak masalah yang timbul dalam mengatasi IDP baik internal maupun eksternal. Kata kunci: konflik komunitas, Maluku. The phenomena of population move as the result of conflict among communities is a problem faced by development, due to population mobility caused by conflict occurs in a huge quantity where this population is categorized as IDP with protection and safety as the reason. The condition is different if migration is performed with economic motive, this means that they have calculate cost and benefit from the purposes of making migration. Since 1970s, there are many population mobility that are performed with impelled manner (Petterson, W, 1996), the example is Africa where due to politic, economic and social condition the individual in the continent have no opportunity to calculate the benefit. While in Indonesia the reform IDP is very high due to conflict between community as the symbol of religion and ethnic. This, of course, contrast with the symbol of Indonesian, namely “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika”, different but one soul, this condition can be seen from 683 multiethnic and there are 5 religions in Indonesia. In fact, if the differences are not managed, the conflict will appear, and this condition will end on open conflict. -

North Maluku and Maluku Recovery Programme

NORTH MALUKU AND MALUKU RECOVERY PROGRAMME 19 September 2001 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 4 II. North Maluku 5 A. Background 5 1. Overview of North Maluku 5 2. The Disturbances and Security Measures 6 3. Community Recovery and Reconciliation Efforts 7 B. Current Situation 12 III. Maluku 14 A. Background 14 1.Overview of Maluku 14 2. The Disturbances and Security Measures 16 3. Community Recovery and Reconciliation Efforts 18 B. Current Situation 20 IV. Reasons for UNDP Support 24 V. Programme Strategy 25 VI. Coordination, Execution, Implementation and Funding Arrangements 28 A. Governing Principles 28 B. Arrangements for Coordination 28 C. UN Agency Partnership and Coordination 29 D. Execution and Implementation Arrangements 30 E. Funding Arrangements 31 VII. Area of Programme Concentration and Target Beneficiaries 32 A. Area of Programme Concentration 32 B. Target Beneficiaries 33 VIII. Development Objective 34 IX. Immediate Objectives 35 X. Inputs 42 XI. Risks 42 XII. Programme Reviews, Reporting and Evaluation 42 XIII. Legal Context 43 XIV. Budget 44 2 Annexes I. Budget II. Terms of Reference of UNDP Trust Fund for Support to the North Maluku and Maluku Recovery Programme III. Terms of Reference: Programme Operations Manager/Team Leader – Jakarta IV. Terms of Reference: Recovery Programme Manager – Ternate and Ambon V. Chart of Reporting, Coordination and Implementation Relationships 3 NORTH MALUKU AND MALUKU RECOVERY PROGRAMME I. INTRODUCTION A. Context This programme of post-conflict recovery in North Maluku and Maluku is part of a wider UNDP effort to support post-conflict recovery and conflict prevention programmes in Indonesia. The wider programme framework for all the conflict-prone and post-conflict areas is required for several reasons. -

Moluccas 15 July to 14 August 2013 Henk Hendriks

Moluccas 15 July to 14 August 2013 Henk Hendriks INTRODUCTION It was my 7th trip to Indonesia. This time I decided to bird the remote eastern half of this country from 15 July to 14 August 2013. Actually it is not really a trip to the Moluccas only as Tanimbar is part of the Lesser Sunda subregion, while Ambon, Buru, Seram, Kai and Boano are part of the southern group of the Moluccan subregion. The itinerary I made would give us ample time to find most of the endemics/specialties of the islands of Ambon, Buru, Seram, Tanimbar, Kai islands and as an extension Boano. The first 3 weeks I was accompanied by my brother Frans, Jan Hein van Steenis and Wiel Poelmans. During these 3 weeks we birded Ambon, Buru, Seram and Tanimbar. We decided to use the services of Ceisar to organise these 3 weeks for us. Ceisar is living on Ambon and is the ground agent of several bird tour companies. After some negotiations we settled on the price and for this Ceisar and his staff organised the whole trip. This included all transportation (Car, ferry and flights), accommodation, food and assistance during the trip. On Seram and Ambon we were also accompanied by Vinno. You have to understand that both Ceisar and Vinno are not really bird guides. They know the sites and from there on you have to find the species yourselves. After these 3 weeks, Wiel Poelmans and I continued for another 9 days, independently, to the Kai islands, Ambon again and we made the trip to Boano. -

Cave Use Variability in Central Maluku, Eastern Indonesia

Cave Use Variability in Central Maluku, Eastern Indonesia D. KYLE LATINIS AND KEN STARK IT IS NOW INCREASINGLY CLEAR that humans systematically colonized both Wallacea and Sahul and neighboring islands from at least 40,000-50,000 years ago, their migrations probably entailing reconnoitered and planned movements and perhaps even prior resource stocking of flora and fauna that were unknown to the destinations prior to human translocation (Latinis 1999, 2000). Interest ingly, much of the supporting evidence derives from palaeobotanical remains found in caves. The number of late Pleistocene and Holocene sites that have been discovered in the greater region including Wallacea and Greater Near Ocea nia, most ofwhich are cave sites, has grown with increased research efforts partic ularly in the last few decades (Green 1991; Terrell pers. comm.). By the late Pleis tocene and early Holocene, human populations had already adapted to a number ofvery different ecosystems (Smith and Sharp 1993). The first key question considered in this chapter is, how did the human use of caves differ in these different ecosystems? We limit our discussion to the geo graphic region of central Maluku in eastern Indonesia (Fig. 1). Central Maluku is a mountainous group of moderately large and small equatorial islands dominated by limestone bedrock; there are also some smaller volcanic islands. The region is further characterized by predominantly wet, lush, tropical, and monsoon forests. Northeast Bum demonstrates some unique geology (Dickinson 2004) that is re sponsible for the distinctive clays and additives used in pottery production (dis cussed later in this paper). It is hoped that the modest contribution presented here will aid others working on addressing this question in larger and different geographic regions. -

Geomaritime-Based Marine and Fishery Economic Development in Di Kabupaten Demak

ISSNISSN 2354-91140024-9521 (online), ISSN 0024-9521 (print) IndonesianIJG Vol. 49, JournalNo.2, June of Geography 2017 (177 -Vol. 185) 49, No.2, December 2017 (177 - 185) ASSESSING THE SPATIAL-TEMPORAL LAND Imam Setyo Hartanto and Rini Rachmawati DOI:© 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.22146/ijg.27668, Faculty of Geography UGM and website: https://jurnal.ugm.ac.id/ijg ©The 2017 Indonesian Faculty of GeographersGeography UGMAssociation and The Indonesian Geographers Association 2507–2522. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-014- 0623-1. Mustopa, Z. (2011). Analisis Faktor-faktor yang Mempengaruhi Alih Fungsi Lahan Pertanian Geomaritime-Based Marine and Fishery Economic Development in di Kabupaten Demak. Diponegoro University. Maluku Islands Retrieved from http://eprints.undip.ac.id/29151/1/ Skripsi015.pdf. (in Bahasa Indonesia). Parker, D. J. (1995). Floodplain development policy Atikah Nurhayati and Agus Heri Purnomo in England and Wales. Applied Geography, 15(4), 341–363. http://doi.org/10.1016/0143- 6228(95)00016-W Received: September 2016 / Accepted: Februari 2017 / Published online: December 2017 © 2017 Faculty of Geography UGM and The Indonesian Geographers Association Pirrone, N., Trombino, G., Cinnirella, S., Algieri, a., Bendoricchio, G., & Palmeri, L. (2005). The Abstract The design of national economic development should never ignore three important aspects, namely integration, and sustainably and local contexts. Insufficient comprehension over these three aspects has caused delays of economic Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) progress in several regions like Maluku. This region is characterized with archipelagic geo-profile where marine and approach for integrated catchment-coastal zone fisheries resources are abundant but economic progress is sluggish. -

Typology and Inequality Between Island Clusters and Development Areas in Maluku Province

Jurnal Perspektif Pembiayaan dan Pembangunan Daerah Vol. 7 No. 2, September - October 2019 ISSN: 2338-4603 (print); 2355-8520 (online) Typology and inequality between island clusters and development areas in Maluku Province Husen Bahasoan1*; Dedi Budiman Hakim2; Rita Nurmalina2; Eka Intan K Putri2 1) Agriculture and Forestry Faculty, Universitas Iqra Buru Maluku, Indonesia 2) Economic and Manajemen Faculty, IPB University Bogor, Indonesia *To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This study aims to analyze patterns of economic growth and island cluster inequality in Maluku Province during the period 2010-2016. The data in this study are secondary data using quantitative descriptive methods and analytical typology analysis tools and theil index. The results showed that the VIII-IX island cluster which was classified as advanced and fast growing but had a very high inequality compared to other island cluster groups was Tual City, Southeast Maluku Regency and Aru Islands Regency. The division of the Maluku region in the Klassen typology is based on the center of growth with the hinterland area. Southern Maluku as a development area is classified as developed and fast-growing where Tual City is a center of growth but has a very high inequality compared to Maluku in the northern region. Keywords: Growth center, Inequality, Island cluster, Klassen typology JEL classification: R10, R11 INTRODUCTION Regional development in general has the aim to develop the region in a better direction by utilizing the potential of the region to prosper the people in the region. The development of an area requires appropriate policies and strategies and programs. -

Mechanisms for the Formation of Ocean Floor Massive Sulfides

Deep-Sea and Sub-Seafloor Resources: A Polymetallic Sulphide and Co-Mn Crust Perspective by Stephen Roberts The LRET Research Collegium Southampton, 16 July – 7 September 2012 1 Deep-Sea and Sub-Seafloor Resources: A Polymetallic Sulphide and Co-Mn Crust Perspective. Stephen Roberts July 2012 Rationale • Ocean floor hydrothermal vent sites, with the associated formation of massive sulfide deposits: – play a fundamental role in the geochemical evolution of the Earth and Oceans, – are a key location of heat loss from the Earth’s interior – provide insights into the formation of ancient volcanogenic massive sulfides. • Furthermore, they are increasingly viewed as attractive sites for the commercial extraction of base metals and gold. • In addition Mn-Co nodules and crusts are increasing recognised as potentially attractive environments for Mn and Cobalt extraction 3 Source: Hannington et al 2011 4 Leg 169 Middle Valley Leg 158 TAG Leg 193 Pacmanus Source: Mid-Ocean Ridges: Hydrothermal Interactions Between the Lithosphere and Oceans, Geophysical Monograph Series 148, C.R. German, J. Lin, and L.M. Parson (eds.), 245–266 (2004) 5 Copyright ©2004 by the American Geophysical Union. Some Key Observations: Circa 2.5-3 Million Tonnes of Massive Sulphide Abundance of anhydrite. Estimate, based on the drilling results, that the TAG mound currently contains about 165,000 metric tons of anhydrite. Through stable and radiogenic isotope analyses of anhydrite insights into circulation of seawater within the deposit. This important mechanism for the formation of Steve Roberts (NOCS) breccias provides a new explanation for the origin of similar breccia ores observed in ancient massive sulfide deposits. -

Digging for the Roots of Language Death in Eastern Indonesia: the Cases of Kayeli and Hukumina

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 384 231 FL 023 076 AUTHOR Grimes, Charles E. TITLE Digging for the Roots of Language Death in Eastern Indonesia: The Cases of Kayeli and Hukumina. PUB DATE Jan 95 NOTE 19p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America (69th, New Orleans, LA, January 5-8, 1995). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) Speeches /Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Diachronic Linguistics; Foreign Countries; *Geographic Location; *Indonesian Languages; *Language Role; Language Usage; Multilingualism; Power Structure; *Uncommonly Taught Languages IDENTIFIERS Indonesia ABSTRACT Looking at descriptive, comparative social and historical evidencB, this study explored factors contributing to language death for two languages formerly spoken on the Indonesian island of Buru. Field data were gathered from the last remaining speaker of Hukumina and from the last four speakers of Kayeli. A significant historical event that set in motion changing social dynamics was the forced relocation by the Dutch in 1656 of a number of coastal communities on this and surrounding islands, which severed the ties between Hukumina speakers and their traditional place of origin (with its access to ancestors and associated power). The same event brought a large number of outsiders to live around the Dutch fort near the traditional village of Kayeli, creating a multiethnic and multilingual community that gradually resulted in a shift to Malay for both Hukumina and Kayeli language communities. This contrasts with the Buru language still spoken as the primary means of daily communication in the island's interior. Also, using supporting evidence from other languages in the area, the study concludes that traditional notions of place and power are tightly linked to language ecology in this region. -

Indonesia's Southern Moluccas

Streak-breasted Fantail (Craig Robson) INDONESIA’S SOUTHERN MOLUCCAS 6 – 23 SEPTEMBER 2019 LEADER: CRAIG ROBSON Of all the birding tours that visit the smaller and more remote islands of Wallacea in Indonesia, this one surely offers the highest number of endemics and, with current taxonomic progress, that number is ever growing. Birdquest was one of the pioneers of tours to the southern Moluccas, and this was our sixth tour to take in Buru, Ambon, Haruku, Yamdena (Tanimbar), Kai, Seram and Boano. Among the many highlights in 2019, were: Moluccan and Tanimbar Megapodes, Tanimbar Cuckoo-Dove, Wallace’s, White-bibbed and Claret-breasted Fruit Doves, Spectacled and Seram Imperial Pigeons, Buru and Seram Mountain Pigeons, 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Indonesia’s Southern Moluccas www.birdquest-tours.com Pygmy Eagle, Rufous-necked Sparrowhawk, Meyer’s Goshawk, Seram, Buru and Tanimbar Boobooks, Lazuli Kingfisher, Tanimbar Corella, Seram (or Salmon-crested) Cockatoo, Yellow-capped Pygmy Parrot, Buru Racket-tail, Purple-naped Lory, Blue-streaked and Blue-eared Lories, South Moluccan, Papuan and Elegant Pittas, Wakolo Myzomela, Buru and Seram Honeyeaters, a trio of endemic friarbird/oriole combos on Buru, Tanimbar and Seram, Island Whistler, Tanimbar, Kai, Seram and Buru Spangled Drongos (if you split them!), likewise Kai, Buru and Seram Fantails, Cinnamon-tailed, Streak-breasted, Tawny-backed and Long-tailed Fantails, an amazing range of island-endemic monarchs (including Boano or Black-chinned), Violet Crow, Golden-bellied Flyrobin, Seram and Buru Golden Bulbuls, Buru, Seram and Kai Leaf Warblers (in the process of being split), the splittable Buru and Seram Bush (or Grasshopper) Warblers, Rufescent Darkeye, Grey-hooded, Pearl-bellied, Golden-bellied, Seram, Buru and Ambon White-eyes, Long-crested Myna, Slaty-backed, Buru, Seram (heard only) and Fawn-breasted Thrushes, Streak-breasted Jungle, Tanimbar and Cinnamon-chested Flycatchers, and Flame-breasted and Ashy Flowerpeckers. -

Territorial Organization by Bupolo People in Buru Island

Territorial Organization by Bupolo People in Buru Island 著者 "PATTINAMA Marcus Jozef" journal or 南太平洋海域調査研究報告=Occasional papers publication title volume 54 page range 79-87 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/24760 南太平洋海域調査研究報告 No.54(2014年12月) OCCASIONAL PAPERS No.54(December 2014) Territorial Organization by Bupolo People in Buru Island PATTINAMA Marcus Jozef Faculty of Agriculture, Pattimura University Abstract To understand Bupolo people in Buru Island, I should start from how I understand the way they divide their life space in association with the environment, namely by understanding the territorial organization of the Bupolo. This understanding will then give a good direction to the understanding of their social organization. Complex division of space in Bupolo people’s lives is something interesting to study. Ethnobotany approach is one of the most suitable methods to be used to describe to complexity. This paper attempts to describe how the Bupolo people in Buru Island, Maluku Province, organize their territory and life spaces. Keywords: Bupolo, Buru Island, territorial organization, ethnobotany Introduction Buru Island is known for being the place of internment of communist prisoners after the establishment of the President Suharto political regime, the “New Order”, following the fall of President Soekarno. Buru is the island that is known to produce the essence oil of kayu putih from the “white tree” (Melaleuca leucadendron, Myrtaceae). This island is in the southwest of the Moluccas, where its coastal regions are considered unwelcoming and dry. People living in the mountains of Buru Island make the essence oil of kayu putih and go to sell it on the coast. -

Small Islands: Protect Or Neglect?

BY SOENARTONO ADISOEMARTO Introduction (47,530,900 ha), Sulawesi (18,614,500 ha), part of the country is located on the Sahul Shelf, Indonesia is a largest archipelagic state situated and Java (13,257,100 ha); including the Papua New Guinea Island (the in the equator, occupying an area bounded by b) much smaller islands of Nusa Tenggara western part of which is the Indonesian Irian L 95oE, L 141oE, M 6oN, and M 11oS, stretches (the Lesser Sunda islands) with a total area Jaya), and its associated Aru Island. for 5,100 km from the Indian to the Pacific of 8,074,000 ha, and Maluku (the Mollucas) This article is focused on the small islands Ocean, with a total land area of 191 million with 7,801,900 ha; of Indonesia, based on the consideration that hectares (MSPE 1993). This geographic area is c) very small islands, which with the larger more comprehensive accounts on these islands associated with territorial waters of some 317 islands make up a total of more than 17,000 may be presented for further purpose. So million hectares and an exclusive economic islands in the archipelago. far, works on small islands in Indonesia are zone (EEZ) of about 473 million hectares. The larger islands such as Sumatra, Java sporadic and over-all outlook has never been These total areas make up about 2,1% of the and Sulawesi, some of the Nusa Tenggara accounted for. This situation has disadvantage globe surface. The total coastline length of the Islands, and some of the smaller islands that the development of the islands may not islands make up about 81,000 km (about 14% such as the Krakatau are greatly influenced be comprehensively planned. -

Download Pdf Chapter VI. NORTH MOLUCCAS

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE GEOLOGY OF INDONESIA AND SURROUNDING AREAS Edition 7.0, July 2018 J.T. VAN GORSEL VI. NORTH MOLUCCAS (incl. Seram, Sula) www.vangorselslist.com VI. NORTH MOLUCCAS VI. NORTH MOLUCCAS ............................................................................................................................... 13 VI.1. Halmahera, Bacan, Waigeo, Molucca Sea ......................................................................................... 13 VI.2. Banggai, Sula, Taliabu, Obi ............................................................................................................... 33 VI.3. Seram, Buru, Ambon ......................................................................................................................... 43 This chapter VI of Bibliography Ed. 7.0 deals with the northernmost part of the Indonesian Archipelago. It contains 67 pages, with 423 titles, and is divided into three sub-chapters. The North Moluccas are a geologically complex region with a number of active volcanic arcs, non-volcanic 'outer arcs', fragments of remnant arcs, microcontinents, and deep basins floored by oceanic crust. VI.1. Halmahera, Bacan, Waigeo, Yapen, Molucca Sea Sub-chapter VI.1. contains 155 references on the geology of the Halmahera region. Figure VI.1.1. Early geologic map of Halmahera- Bacan- Waigeo (Verbeek 1908) Bibliography of Indonesian Geology, Ed. 7.0 1 www.vangorselslist.com July 2018 This area of N Indonesia is in the realm of the western Pacific Ocean (Philippine Sea Plate). The western part is the Molucca Sea complex, where Molucca Sea Plate oceanic crust is subducting in two directions, under Halmahera in the East and the Sangihe arc in the West. The S side is bordered by the Sorong Fault zone, a major strike slip zone separating the W-moving Pacific from a N-moving Australia- New Guinea plate. Islands are composed of fragments of Late Cretaceous- M Eocene and younger island arc volcanics, intruded into and overlying collisional complexes with Jurassic or Cretaceous-age ophiolites.