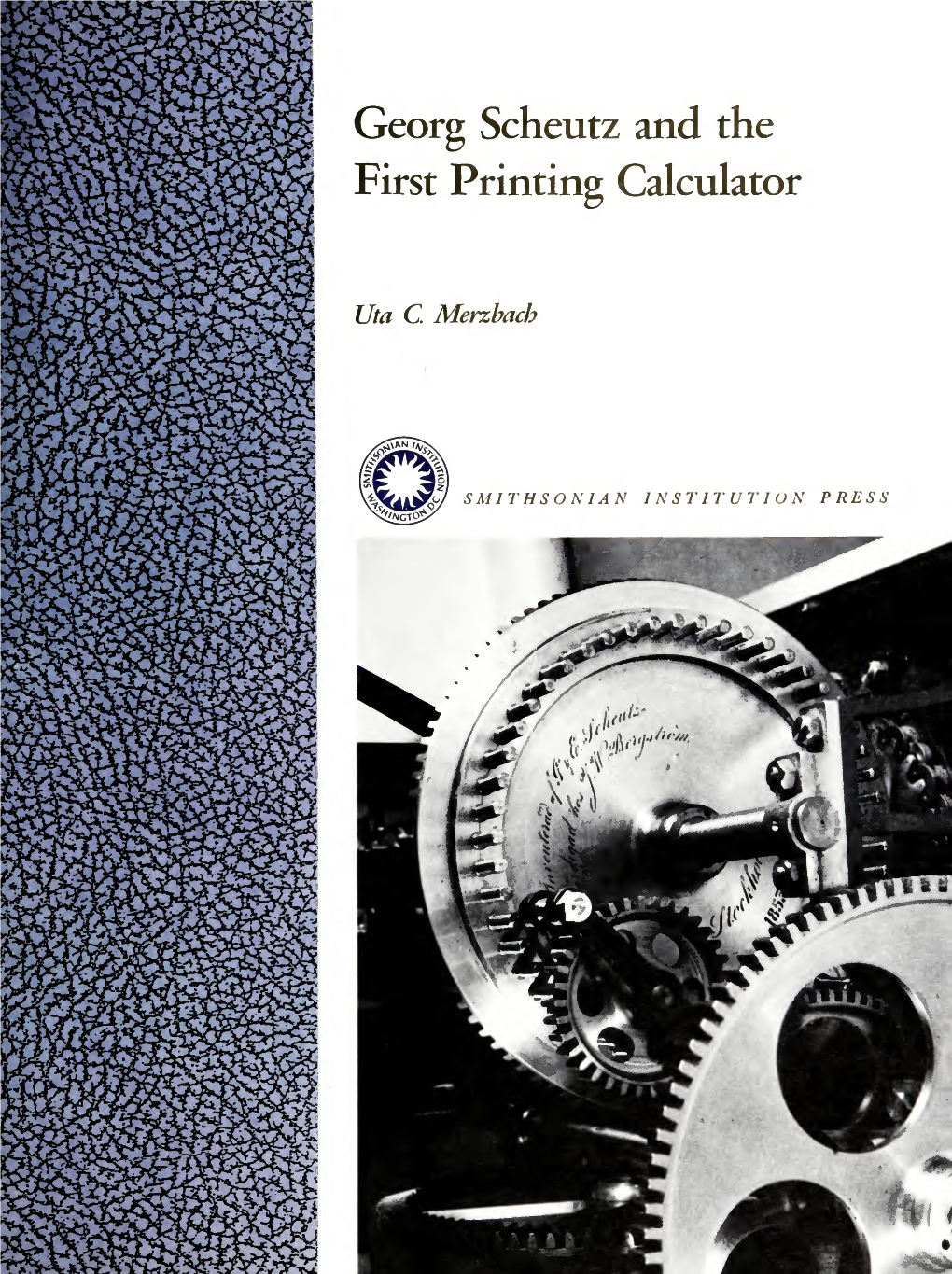

Georg Scheutz and the First Printing Calculator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Computers" Abacus—The First Calculator

Component 4: Introduction to Information and Computer Science Unit 1: Basic Computing Concepts, Including History Lecture 4 BMI540/640 Week 1 This material was developed by Oregon Health & Science University, funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology under Award Number IU24OC000015. The First "Computers" • The word "computer" was first recorded in 1613 • Referred to a person who performed calculations • Evidence of counting is traced to at least 35,000 BC Ishango Bone Tally Stick: Science Museum of Brussels Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 2 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Abacus—The First Calculator • Invented by Babylonians in 2400 BC — many subsequent versions • Used for counting before there were written numbers • Still used today The Chinese Lee Abacus http://www.ee.ryerson.ca/~elf/abacus/ Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 3 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 1 Slide Rules John Napier William Oughtred • By the Middle Ages, number systems were developed • John Napier discovered/developed logarithms at the turn of the 17 th century • William Oughtred used logarithms to invent the slide rude in 1621 in England • Used for multiplication, division, logarithms, roots, trigonometric functions • Used until early 70s when electronic calculators became available Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 4 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Mechanical Computers • Use mechanical parts to automate calculations • Limited operations • First one was the ancient Antikythera computer from 150 BC Used gears to calculate position of sun and moon Fragment of Antikythera mechanism Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 5 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Leonardo da Vinci 1452-1519, Italy Leonardo da Vinci • Two notebooks discovered in 1967 showed drawings for a mechanical calculator • A replica was built soon after Leonardo da Vinci's notes and the replica The Controversial Replica of Leonardo da Vinci's Adding Machine . -

Analytical Engine, 1838 ALLAN G

Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, 1838 ALLAN G. BROMLEY Charles Babbage commenced work on the design of the Analytical Engine in 1834 following the collapse of the project to build the Difference Engine. His ideas evolved rapidly, and by 1838 most of the important concepts used in his later designs were established. This paper introduces the design of the Analytical Engine as it stood in early 1838, concentrating on the overall functional organization of the mill (or central processing portion) and the methods generally used for the basic arithmetic operations of multiplication, division, and signed addition. The paper describes the working of the mechanisms that Babbage devised for storing, transferring, and adding numbers and how they were organized together by the “microprogrammed” control system; the paper also introduces the facilities provided for user- level programming. The intention of the paper is to show that an automatic computing machine could be built using mechanical devices, and that Babbage’s designs provide both an effective set of basic mechanisms and a workable organization of a complete machine. Categories and Subject Descriptors: K.2 [History of Computing]- C. Babbage, hardware, software General Terms: Design Additional Key Words and Phrases: Analytical Engine 1. Introduction 1838. During this period Babbage appears to have made no attempt to construct the Analytical Engine, Charles Babbage commenced work on the design of but preferred the unfettered intellectual exploration of the Analytical Engine shortly after the collapse in 1833 the concepts he was evolving. of the lo-year project to build the Difference Engine. After 1849 Babbage ceased designing calculating He was at the time 42 years o1d.l devices. -

A Bibliography of Publications By, and About, Charles Babbage

A Bibliography of Publications by, and about, Charles Babbage Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 08 March 2021 Version 1.24 Abstract -analogs [And99b, And99a]. This bibliography records publications of 0 [Bar96, CK01b]. 0-201-50814-1 [Ano91c]. Charles Babbage. 0-262-01121-2 [Ano91c]. 0-262-12146-8 [Ano91c, Twe91]. 0-262-13278-8 [Twe93]. 0-262-14046-2 [Twe92]. 0-262-16123-0 [Ano91c]. 0-316-64847-7 [Cro04b, CK01b]. Title word cross-reference 0-571-17242-3 [Bar96]. 1 [Bab97, BRG+87, Mar25, Mar86, Rob87a, #3 [Her99]. Rob87b, Tur91]. 1-85196-005-8 [Twe89b]. 100th [Sen71]. 108-bit [Bar00]. 1784 0 [Tee94]. 1 [Bab27d, Bab31c, Bab15]. [MB89]. 1792/1871 [Ynt77]. 17th [Hun96]. 108 000 [Bab31c, Bab15]. 108000 [Bab27d]. 1800s [Mar08]. 1800s-Style [Mar08]. 1828 1791 + 200 = 1991 [Sti91]. $19.95 [Dis91]. [Bab29a]. 1835 [Van83]. 1851 $ $ $21.50 [Mad86]. 25 [O’H82]. 26.50 [Bab51a, CK89d, CK89i, She54, She60]. $ [Enr80a, Enr80b]. $27.95 [L.90]. 28 1852 [Bab69]. 1853 [She54, She60]. 1871 $ [Hun96]. $35.00 [Ano91c]. 37.50 [Ano91c]. [Ano71b, Ano91a]. 1873 [Dod00]. 18th $45.00 [Ano91c]. q [And99a, And99b]. 1 2 [Bab29a]. 1947 [Ano48]. 1961 Adam [O’B93]. Added [Bab16b, Byr38]. [Pan63, Wil64]. 1990 [CW91]. 1991 Addison [Ano91c]. Addison-Wesley [Ano90, GG92a]. 19th [Ano91c]. Addition [Bab43a]. Additions [Gre06, Gre01, GST01]. -

The Calculating Machines of Charles Babbage

The Little Engines that Could've: The Calculating Machines of Charle... http://robroy.dyndns.info/collier/ Preface Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 The Little Engines that Could've: The Calculating Machines of Charles Babbage A thesis presented by Bruce Collier to The Department of History of Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August, 1970 Copyright reserved by the author. Preface Charles Babbage's invention of the computer is something like the weather. Everyone working with computers for the last two decades has been talking about it, but nothing has been done. Every historical introduction to a computer text contains a section on Babbage, often extensive; but they are all based on the quite scanty information about the Analytical Engine published during the nineteenth century. The immense amount of manuscript material concerning Babbage extant in England has remained essentially untouched. The one hoped for exception was Maboth Moseley's Irascible Genius (London, 1964). a full length biography of Babbage. Moseley consulted the Babbage correspondence at the British Museum and the unpublished biography of Babbage written by his friend Harry Wilmot Buxton; yet despite the fact that Moseley was the editor of a computer journal, she did not examine Babbage's notebooks and drawings, now in the Science Museum in South Kensington, and her book contains virtually nothing of interest on the Analytical Engine. On the whole, Irascible Genius is a good deal less interesting than Babbage's own volume of memoirs, Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (London, 1864), and it is no more balanced, and not very much more accurate. -

Förteckning Över

Förteckning över: 1) De la Gardieska släktarkivet från Löberöd; 2) Varia; 3) De övriga släktarkiven i De la Gardieska arkivet (dvs Barnekow, Bille, Boije, Douglas, Ekeblad, Forbus, Gyllenkrook, Horn - von Gertten, Hägerstierna, Kruus, Kämpe, Königsmarck, Lillie, Månsson, Nils, i Skumparp, Oxenstierna, Ramel, Reenstierna, von Reiser, Sparre, Stenbock, Sture, Wrangel, Wrede) upprättad 2008 av Annika Böregård Vapenförbättringsbrev för Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, 1650 Universitetsbiblioteket, Lunds universitet 1 De la Gardieska samlingen Släktarkiven De la Gardie De la Gardie är en grevlig släkt, härstammande från en fransk borgarsläkt som på oklara grunder tillskrivits adlig status. En del av släkten var dock möjligen lokal lantadel; om det råder delade meningar i forskningen. I Frankrike hette släkten d´Escouperie och den förste kände stamfadern var Robert d´Escouperie (levde omkr. 1387), som uppges ha ägt gårdarna Château Russol och La Gardie i departementet Aude. Släktens svenska gren härstammar från köpmannen Jacques Scoperier (†1565) i staden Caunes nära Carcassonne i södra Frankrike. Hans son Ponce d´Escouperie invandrade till Sverige 1565 och antog namnet Pontus De la Gardie efter en av släktens gårdar i Languedoc. I sitt äktenskap med en illegitim dotter till Johan III blev han far till riksmarsken Jakob de la Gardie som "upphöjdes i grefligt stånd" 10 maj 1615 och introducerades 1625 på Sveriges Riddarhus med nr 3 bland grevar. Denna gren finns fortfarande. I Sverige fanns en gren som 1571 fick friherrelig värdighet men som utslocknade 1640. Samtliga ättemedlemmar, bortsett från stamfadern Pontus, härstammar via hans fru Sofia Johansdotter från hennes far, Johan III. Nuvarande (2007) huvudman för ätten De la Gardie är greve Carl Gustaf De la Gardie, f.1946 och bosatt i Linköping. -

Arv Nordic Yearbook of Folklore 2015 2 3 ARVARV Nordic Yearbook of Folklore Vol

1 Arv Nordic Yearbook of Folklore 2015 2 3 ARVARV Nordic Yearbook of Folklore Vol. 71 Editor ARNE BUGGE AMUNDSEN OSLO, NORWAY Editorial Board Anders Gustavsson, Oslo; Gustav Henningsen, Copenhagen Bengt af Klintberg, Lidingö; Ann Helene Bolstad Skjelbred, Oslo Ulrika Wolf-Knuts, Åbo (Turku) Published by THE ROYAL GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS ACADEMY UPPSALA, SWEDEN Distributed by SWEDISH SCIENCE PRESS UPPSALA, SWEDEN 4 © 2015 by The Royal Gustavus Adolphus Academy, Uppsala ISSN 0066-8176 All rights reserved Articles appearing in this yearbook are abstracted and indexed in European Reference Index for the Humanities and Social Sciences ERIH PLUS 2011– Editorial address: Prof. Arne Bugge Amundsen Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo Box 1010 Blindern NO–0315 Oslo, Norway phone + 4792244774 fax + 4722854828 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.hf.uio.no/ikos/forskning/publikasjoner/tidsskrifter/arv/index.html Cover: Kirsten Berrum For index of earlier volumes, see http://www.kgaa.nu/tidskrift.php Distributor Swedish Science Press Box 118, SE–751 04 Uppsala, Sweden phone: +46(0)18365566 fax: +46(0)18365277 e-mail: [email protected] Printed in Sweden Textgruppen i Uppsala AB, Uppsala 2015 5 Contents Articles Ulrika Wolf-Knuts: Scepticism and Broad-mindedness in Talk of Paedophilia . 7 Amber J. Rose: The Witch on the Wall: The Milk-Stealing Witch in Scandinavian Iconography . 27 Jason M. Schroeder: Ruins and Fragments: A Case Study of Ballads, Fragments and Editorial Echolarship in Svenska folk- visor från forntiden . 45 Rósa Þorsteinsdóttir: “Ég kann langar sögur um kónga og drottningar”: Eight Icelandic Storytellers and their Fairy Tales . -

Analytical Engine: the Orig- Inal Computer

Chapter 2 Analytical Engine: The Orig- inal Computer As we learned in the fourth grade science course, back in 1801, a French man, Joseph Marie Jacquard, invented a power loom that could weave textiles, which had been done for a long time by hand. More interestingly, this machine can weave tex- tiles with patterns such as brocade, damask, and matelasse by controlling the operation with punched wooden cards, held together in a long row by rope. 1 How do these cards work? Each wooden card comes with punched holes, each row of which corresponds to one row of the design. In each position, if the needle needs to go through, there is a hole; other- wise, there is no hole. Multiple rows of holes are punched on each card and all the cards that compose the design of the textile are hooked together in order. 2 What do we get? With the control of such cards, needs go back and forth, moving from left to the right, row by row, and come up with something like the following: Although the punched card concept was based on some even earlier invention by Basile Bou- chon around 1725, “the Jacquard loom was the first machine to use punch cards to con- trol a sequence of operations”. Let’s check out a little demo as how Jacquard’s machine worked. 3 Why do we talk about a loom? With Jacquard loom, if you want to switch to a different pattern, you simply change the punched cards. By the same token, with a modern computer, if you want it to run a different application, you simply load it with a different program, which used to keep on a deck of paper based punched cards. -

THE JVEDIS. ART SONG Presented to the Graduate Council of the North

110,2 THE JVEDIS. ART SONG THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial ifillment of the requirements For the Degree of MAST ER OF MUSIC by 223569 Alfred R. Skoog, B. Mus. Borger, Texas August, 1953 223569 PREFACE The aim of this thesis is to present a survey of Swedish vocal music, a subject upon which nothing in English exists and very little in Swedish. Because of this lack of material the writer, who has spent a year (195152) of research in music in Sweden, through the generosity of Mrs. Alice M. Roberts, the Texas Wesleyan Academy, and the Texas Swedish Cultural Foundation, has been forced to rely for much of his information on oral communication from numerous critics, composers, and per- formers in and around Stockholm. This accounts for the paucity of bibliographical citations. Chief among the authorities consulted was Gsta Percy, Redaktionssekreterare (secretary to the editor), of Sohlmans Jusiklexikon, who gave unstintedly, not only of his vast knowledge, but of his patience and enthusiasm. Without his kindly interest this work would have been impossible, iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page . 1.F. .:.A . !. !. ! .! . .! ! PREFACE.! . ! .0 01 ! OF LIST ITLISTRATITONS. - - - . a- . a . V FORH4ORD . .* . .- . * .* . * * * * * * * . vii Chapter I. EARLYSEDIS0H SONG. I The Uppsala School II. NINETEENTH CENTURY NATIONALISTS . 23 The Influence of Mid-Nineteenth Century German Romanticism (Mendelssohn, Schumann, Liszt and Wagner) The French Influence III. LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY ND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY COMPOSERS . 52 Minor Vocal Composers of the Late Nine- teenth Century and Early Twentieth Century IV. THE MODERN SCHOOL OF S7E)ISl COMPOSERS. -

History of Computing Prehistory – the World Before 1946

Social and Professional Issues in IT Prehistory - the world before 1946 History of Computing Prehistory – the world before 1946 The word “Computing” Originally, the word computing was synonymous with counting and calculating, and a computer was a person who computes. Since the advent of the electronic computer, it has come to also mean the operation and usage of these machines, the electrical processes carried out within the computer hardware itself, and the theoretical concepts governing them. Prehistory: Computing related events 750 BC - 1799 A.D. 750 B.C. The abacus was first used by the Babylonians as an aid to simple arithmetic at sometime around this date. 1492 Leonardo da Vinci produced drawings of a device consisting of interlocking cog wheels which could be interpreted as a mechanical calculator capable of addition and subtraction. A working model inspired by this plan was built in 1968 but it remains controversial whether Leonardo really had a calculator in mind 1588 Logarithms are discovered by Joost Buerghi 1614 Scotsman John Napier invents an ingenious system of moveable rods (referred to as Napier's Rods or Napier's bones). These were based on logarithms and allowed the operator to multiply, divide and calculate square and cube roots by moving the rods around and placing them in specially constructed boards. 1622 William Oughtred developed slide rules based on John Napier's logarithms 1623 Wilhelm Schickard of Tübingen, Württemberg (now in Germany), built the first discrete automatic calculator, and thus essentially started the computer era. His device was called the "Calculating Clock". This mechanical machine was capable of adding and subtracting up to 6 digit numbers, and warned of an overflow by ringing a bell. -

P. G. Scheutz, Publicist, Author, Scientific Gineer—Biography And

238 p. g. scheutz and edvard scheutz I. Department: War Branch or Bureau: Ordnance Department Description of activity: A. Moore School of Electrical Engineering, Construction of an electronic digital machine ("EDVAC"). B. Institute for Advanced Study and RCA Labs., Princeton, N. J. Construction of an electronic digital machine (financed only in part by federal funds). C. National Bureau' of Standards, Washington, D, C, Long-range component development program. II. Department: Navy Branch or Bureau: Office of Naval Research Description of Activity: A. National Bureau of Standards, Construction of an electronic digital machine. B. Servomechanisms Lab., Mass, Institute of Technology, Construction of an electronic digital machine to be used in a large guided-missile flight simulator. III. Department: Navy Branch or Bureau: Bureau of Ordnance Description of Activity : A. Harvard Computation Lab., Research and preparation of specifications for an electronic digital machine. B. Naval Ordnance Lab., White Oaks, Md., Construction of an electronic digital machine, temporarily abandoned (Dec. 1946). IV. Department: Commerce Branch or Bureau: Bureau of the Census Description of Activity: National Bureau of Standards, Construction of an electronic digital machine. J. H. Curtiss National Bureau of Standards Editorial Note: Other projected digital machines, unaided in their construction by the U. S. Government, are being built by: (i) The Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, N. Y. (ii) The University of California, Berkeley. (iii) The National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, England, under the direction of Dr. Alan M. Turing. The planned Automatic Computing Engine will work at the speed of the ENIAC or possibly somewhat higher, and will take advantage of new technical developments, making possible both a greater memory capacity and a higher degree of complexity in the instructions. -

Den Svenska Lantbrukskooperationens Bakgrund, Framväxt Och Utveckling Till 1930: Inspiratörer, Idéutveckling Och Praxis

Den svenska lantbrukskooperationens bakgrund, framväxt och utveckling till 1930: inspiratörer, idéutveckling och praxis Ett ej färdigställt manuskript av Tore Johansson (1937–2010), fil. lic. och arkivarie vid LRF. Innehållet är av stort intresse för forskningen om svenska lantbrukskooperationens framväxt och utveckling varför det publiceras i ofärdigt skick. INNEHÅLL 1. FÖRE NÄRINGSFRIHETEN 1.1 EKONOMISKA VERKSAMHETSFORMER I AGRARSAMHÄLLET 1.1.1 Olaus Magnus och den inbördes hjälpen 1.1.2 Lagbildningarna 1.1.2.1 By och byalag 1.1.2.2 Samägande och samdrift i lantbruket 1.1.2.3 Arbetsbyten 1.1.2.4 Arbetsinvandringar och arbetslag 1.1.2.5 Skeppslag och bondeseglation 1.1.2.6 Bergsmän och bergslag 1.1.2.7 Fiskelagen 1.1.3 Sockenmagasinen 1.1.4 Brandstod och brandförsäkring 1.1.5 Försvar och kommunikationer 1.2 SAMVERKAN UNDER SKIFTANDE VILLKOR 1.2.1 Samfund i omvandling 1.2.1.1 Förändringsagenter 1.2.1.2 Skatterna 1.2.1.3 Samhället och lagbildningarna 1.2.1.4 Ståndssamhällets avveckling 1.2.2 Det stadsekonimiska systemet 1.2.2.1 Handeln 1.2.2.2 Stadspolitikernas framväxt 1.2.2.3 Marknaderna 1.2.2.4 Hantverket 1.2.3 De ekonomiska doktrinerna 1.2.3.1 Merkantilismen 1.2.3.2 Fysiokraterna 1.2.3.3 Doktrinerna i Sverige 1.2.3.4 Den tidiga landsbygdsindustrin 1.2.3.5 Näringsfrihet och självhjälp 1846 1.2.4 Kropotkin, Hasslöf och den inbördes hjälpen 1.2.4.1 Samverkans guldålder 1.2.4.2 Nedgång och pånyttfödelse 1.2.4.3 Samverkan och konkurrens 1.2.4.4 En ofullbordad ansats 1.2.4.5 Olof Hasslöf och allmogens lagbildningar 1.3 EKONOMISKA INITIATIV -

Det Åndelige Klima I Sverige Efter Mordet På Gustaf III

Det åndelige klima i Sverige efter mordet på Gustaf III af docent, fd.dr. Gunnar Syréhn, Institut for nordisk filologi, Københavns Universitet Der findes en scene i Lars Forssells teaterstykke Galenpannan (Galfrans), som har fascineret mig lige siden jeg stødte på den første gang. Personen, der kaldes Galen pannan, men som egentlig forestiller Sveriges afsatte konge, Gustaf IV Adolf, sidder som landflygtig nede i Sankt Gallen og drømmer om at fa lov at dø på samme måde som faderen Gustaf III, nemlig ved et pistolskud. Dette bliver ham dog ikke forundt; han dør på scenen ligesom i virkeligheden af et slagtilfælde, men lige før han falder om, råber han teatralsk og triumferende: "Der kom skuddet!"1 Dermed er cirklen sluttet; mordet på Gustaf III i 1792 blev, som vi ved, slut ningen på en æra i svensk historie og naturligvis samtidig begyndelsen på en ny tid, og hvis det er sandt, at historien er kongernes, som Erik Gustaf Geijer opfattede det, så afsluttedes denne epoke med afsættelsen af Gustav IV Adolf i 1809. Mellem de poler som udgøres af Gustaf IIIs død og revolutionen i 1809 vil også min fremstilling hovedsageligt bevæge sig. Som vi ved, nærede Bellman en gensidig kærlighed til Gustaf III, og hans hyldester kan synes rørende i deres uskyldige underdanighed. Fredmans sang nr 64 "Fjåriln vingad syns på Haga", afsluttes med den tanke, at den, som rammes af Gustafs blide blik, begynder at græde af taknemmelighed, og at den sørgende bliver glad bare monarken ser på ham.2 Eller tag "Gustafs skål", som skjalden skrev for at hylde kongen ved den ublodige revolution i 1772, og hvor han lovpriser Gustaf III som "Den bedste konge, som Norden ejer", en som ikke bare er "God og glad", men tillige retfærdig og udrustet med evnen til at gennemskue dårskab.3 42 "Gustafs skål" har et søsterdigt som begynder med ordene "Således lyser din krone nu, Kong Gustaf, dobbelt dyrebar".4 I et andet teaterstykke af Lars Forssell, Haren og Musvågen, har skælmen Guntlack faet fat i manuskriptet til denne sang og bebrejder Bellman hans devote hyldester til kongen.