On the Biogeographical Significance of Protected Forest Areas In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wo Conservative Prefects: Nicolae P. Guran and Constantin Radu Geblescu1 T

JOURNAL of Humanities, Culture and Social Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2018 ISSN 2393 – 5960; ISSN – L 2393-5960, pp. 10-25 wo conservative prefects: Nicolae P. Guran and Constantin Radu Geblescu1 T Mirela-Minodora Mincă-Mălăescu, Ph.D.c. Counsellor, Romanian National ArChives, Dolj County Department Romania [email protected] Abstract In the present study we approaCh the aCtivity of NiColae P. Guran and Constantin Radu GeblesCu, two of Dolj County prefeCts from the end of the 19th Century, and the beginning of the 20th Century. Two Conservatives, whose activity was foCused on the supporting of the rural education and Culture, they also Considered that the issue on addressing the modernisation of Romania Could be aCComplished only through the eduCation of the rural population and the improvement of the living Conditions (Coord. ACad. Gheorghe Platon: 2003: 191-207). The building of sChools and hospitals, the spreading of Culture through education and the learning of minimal hygiene norms were few of the objectives of the two Conservative prefeCts, who supported finanCially, from the budget of the County, the ConstruCtion of sChools and hospitals, along with the reorganisation of the Superior Trade SChool, where the Children from the rural areas were obtaining high qualificationforms. NiColae P. Guran and Constantin Radu GeblesCu filled the position of prefeCt in Dolj County, between the 12th of April 1899 and the 14th of February 1901, respeCtively the 24th of DeCember 1904 and the 12th of MarCh 1907. Keywords: activity, prefeCt, Dolj, Guran, GeblesCu. 1 The present study is part of the doCtor degree researCh project: The institution of the prefect in Dolj County, during the reign of Carol I, Carried outbetween 2015 and 2018, within the SoCial Sciences Faculty. -

Evaluation of the CAP Measures Applicable to the Wine Sector

Evaluation of the CAP measures applicable to the wine sector Case study report: Romania Written by Agrosynergie EEIG Agrosynergie November – 2018 Groupement Européen d’Intérêt Economique AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development Directorate C – Strategy, simplification and policy analysis Unit C.4 – Monitoring and Evaluation E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Evaluation of the CAP measures applicable to the wine sector Case study report: Romania Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development 2018 EN Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019 Catalogue number: KF-05-18-079-EN-N ISBN: 978-92-79-97275-1 doi: 10.2762/62004 © European Union, 2018 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Images © Agrosynergie, 2018 EEIG AGROSYNERGIE is formed by the following companies: ORÉADE-BRÈCHE Sarl & COGEA S.r.l. -

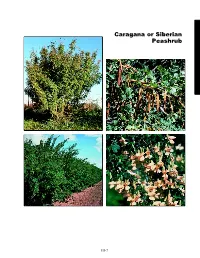

Caragana Or Siberian Peashrub

Caragana or Siberian Peashrub slide 5a 400% slide 5b 360% slide 5d slide 5c 360% 360% III-7 Caragana or Environmental Requirements Siberian Peashrub Soils Soil Texture - Adapted to a wide range of soils. (Caragana Soil pH - 5.0 to 8.0. arborescens) Windbreak Suitability Group - 1, 1K, 3, 4, 4C, 5, 6D, 6G, 8, 9C, 9L. General Description Cold Hardiness USDA Zone 2. Drought tolerant legume, long-lived, alkaline-tolerant, tall shrub native to Siberia. Ability to withstand extreme cold Water and dryness. Major windbreak species. Drought tolerant. Does not perform well on very wet or very dry sandy soils. Leaves and Buds Bud Arrangement - Alternate. Light Bud Color - Light brown, chaffy in nature. Full sun. Bud Size - 1/8 inch, weakly imbricate. Leaf Type and Shape - Pinnately-compound, 8 to 12 Uses leaflets per leaf. Conservation/Windbreaks Leaf Margins - Entire. Medium to tall shrub for farmstead and field windbreaks Leaf Surface - Pubescent in early spring, later glabrescent. and highway beautification. Leaf Length - 1½ to 3 inches; leaflets 1/2 to 1 inch. Wildlife Leaf Width - 1 to 2 inches; leaflets 1/3 to 2/3 inch. Used for nesting by several species of songbirds. Food Leaf Color - Light-green, become dark green in summer; source for hummingbirds. yellow fall color. Agroforestry Products Flowers and Fruits No known products. Flower Type - Small, pea-like. Flower Color - Showy yellow in spring. Urban/Recreational Fruit Type - Pod, with multiple seeds. Pods open with a Screening and border, ornamental flowers in spring. popping sound when ripe. Cultivated Varieties Fruit Color - Brown when mature. -

Perspectives of the Business Area Development in the Romanian Rural Area

НАУЧНИ ТРУДОВЕ НА РУСЕНСКИЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ - 2013, том 52, серия 5.1 Perspectives of the business area development in the Romanian rural area. Case study Calarasi county Daniela Cretu1 Elena Lascăr2 Abstract: The rural area in Călăraşi county has a particular importance for the development of the county, so its analysis wants to identify the vital positive and negative elements for its sustainable development. With a decreasing population and its density of about 61 inhabitants/km should be considered mainly a predominant rural county, with over half of the population in rural area in 2012, which represents a much higher value than the average of the recently integrated EU countries. Thus, the rural and agricultural development will form a solid pillar. The success and prosperity of the county depend on their economic performances. The county is dependent on agriculture and on rural economy. The spread of globalization threatens the traditional agriculture. Key words: agriculture, active population, employed population, investments, rural area resources. INTRODUCTION Călăraşi county is part of South-Muntenia development Region, it was declared as territorial-administrative unit in January 1981, it is situated in the South-East part of Romania, on the left shore of the Danube and Borcea Branch and it borders in the North with Ialomiţa county, in the East with Constanţa county, in the West with Giurgiu county and Ilfov Agricultural Sector and in the South with Bulgaria [2]. The county has a surface of 508,785 ha, representing 2.1% of Romania, Călăraşi county occupies 28th place among the country counties [4]. From administrative point of view, the county contains 2 municipalities, 3 towns, 50 communes and 161 villages. -

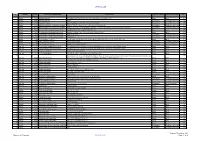

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

American Smoketree (Cotinus Obovatus Raf.)

ACADBJIY OJl'· SCIBNCm FOR 1M2 11 o AMERICAN SMOKETREE (COTINUS OBOVATUS RAP.), ONE OF OKLAHOMA'S RAREST TREE SPECIES ELBERT L. LITTLE, IlL, Forest Senlee United States DepartmeDt of J.grlealture, Washington, D. C. Though the American Smoketree was discovered in Oklahoma by Thomu Nuttall in 1819, only one more collection of this rare tree species within the state has been reported. This article summarizes these records, add8 a third Oklahoma locality, and calle attention to the older lClenttf1c name, Cotfftu ob0'V4tu Ral, which 8hould replace the one In ue, Coth," (lm.en. eo".. Hutt. II PROCDDINGS OJ' THE OKLAHOMA Nattall (1821), the flnt botaDl8t to mit what 11 now Okahoma, men tlODed In hie journal for July 18, 1819, the dl8covery, to his great 81U'Prlse, of thla new, Jarp Ihrub, aearcely dlltlnet from BA.. cot'"'' of Europe. He deIcrlbed the location as on l1mestone clUb of the Grand (or Neosho) RITer near a bend called the Eagle'e Neat more tban thirty miles north of the confluence of the Grand and Arkanlla8 River.. The place probably ..... alODC the 8< bank of the river In eoutheastern Mayes County, at the weetern edge of the Ozark Plateau in northeastern Oklahoma. It 11 hoped that Oklahoma botaDleti w1ll revisit the type locality and a1eo die. COTer other etatloD•. Thll Dew species was Dot mentioned In Nuttall'. (1837) unfinished publication on his collections of the flora of Arkansas Territory. Torrey aD4 Gray (1888) IDcluded Nuttall's frultfng specimens doubtfully under the related European species, then known as Rhu coUnu L., with Nuttall's upubllehed herbariUM Dame, Bh., coUnoUles Nutt., as a synonym. -

Ana Petrova, Vladimir Vladimirov, Valeri Georgiev, Adventive Alien

CONTENTS CAMELIA IFRIM, IULIANA GAŢU – Morphological features concerning epidermal appendages on some species of the Solanum genus .......................................................... 3 JABUN NAHAR SYEDA, MOSTAFIZUL HAQUE SYED, KAZUHIKO SHIMASAKI – Organogenesis of Cymbidium orchid using elicitors ..................................................... 13 SHIPRA JAISWAL, MEENA CHOUDHARY, SARITA ARYA, TARUN KANT – Micropropagation of adult tree of Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb. using nodal explants ... 21 DELESS EDMOND FULGENCE THIEMELE, AUGUSTE EMMANUEL ISSALI, SIAKA TRAORE, KAN MODESTE KOUASSI, NGORAN ABY, PHILIPPE GOLY GNONHOURI, JOSEPH KOUMAN KOBENAN, THÉRÈSE NDRIN YAO, AMONCHO ADIKO, ASSOLOU NICODÈME ZAKRA – Macropropagation of plantain (Musa spp.) Cultivars PITA 3, FHIA 21, ORISHELE and CORNE 1: effect of benzylaminopurine (BAP) concentration ...................................................................... 31 JAIME A. TEIXEIRA DA SILVA – Alterations to PLBs and plantlets of hybrid Cymbidium (Orchidaceae) in response to plant growth regulators ................................................... 41 GULSHAN CHAUDHARY, PREM KUMAR DANTU – Evaluation of callus browning and develop a strategically callus culturing of Boerhaavia diffusa L. .................................. 47 PANDU SASTRY KAKARAPARTHI, K. V. N. SATYA SRINIVAS, J. KOTESH KUMAR, A. NIRANJANA KUMAR, ASHISH KUMAR – Composition of herb and seed oil and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of two varieties of Ocimum basilicum harvested at short time intervals ................................................................................... -

Horner-Mclaughlin Woods Compiled by Bev Walters, 2011-2012

Horner-McLaughlin Woods Compiled by Bev Walters, 2011-2012 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Acer negundo BOX-ELDER Acer nigrum (A. saccharum) BLACK MAPLE Acer rubrum RED MAPLE Acer saccharinum SILVER MAPLE Acer saccharum SUGAR MAPLE Achillea millefolium YARROW Actaea pachypoda DOLL'S-EYES Adiantum pedatum MAIDENHAIR FERN Agrimonia gryposepala TALL AGRIMONY Agrimonia parviflora SWAMP AGRIMONY Agrimonia pubescens SOFT AGRIMONY AGROSTIS GIGANTEA REDTOP Agrostis perennans AUTUMN BENT Alisma subcordatum (A. plantago-aquatica) SOUTHERN WATER-PLANTAIN Alisma triviale (A. plantago-aquatica) NORTHERN WATER-PLANTAIN ALLIARIA PETIOLATA GARLIC MUSTARD Allium tricoccum WILD LEEK Ambrosia artemisiifolia COMMON RAGWEED Amelanchier arborea JUNEBERRY Amelanchier interior SERVICEBERRY Amphicarpaea bracteata HOG-PEANUT Anemone quinquefolia WOOD ANEMONE Anemone virginiana THIMBLEWEED Antennaria parlinii SMOOTH PUSSYTOES Apocynum androsaemifolium SPREADING DOGBANE ARCTIUM MINUS COMMON BURDOCK Arisaema triphyllum JACK-IN-THE-PULPIT Asarum canadense WILD-GINGER Asclepias exaltata POKE MILKWEED Asclepias incarnata SWAMP MILKWEED Asplenium platyneuron EBONY SPLEENWORT Athyrium filix-femina LADY FERN BERBERIS THUNBERGII JAPANESE BARBERRY Bidens cernua NODDING BEGGAR-TICKS Bidens comosa SWAMP TICKSEED Bidens connata PURPLE-STEMMED TICKSEED Bidens discoidea SWAMP BEGGAR-TICKS Bidens frondosa COMMON BEGGAR-TICKS Boehmeria cylindrica FALSE NETTLE Botrypus virginianus RATTLESNAKE FERN BROMUS INERMIS SMOOTH BROME Bromus pubescens CANADA BROME Calamagrostis canadensis BLUE-JOINT -

Producción De Forraje Y Competencia Interespecífica Del Cultivo Asociado De Avena (Avena Sativa) Con Vicia (Vicia Sativa) En Condiciones De Secano Y Gran Altitud

Rev Inv Vet Perú 2018; 29(4): 1237-1248 http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rivep.v29i4.15202 Producción de forraje y competencia interespecífica del cultivo asociado de avena (Avena sativa) con vicia (Vicia sativa) en condiciones de secano y gran altitud Forage production and interspecific competition of oats (Avena sativa) and common vetch (Vicia sativa) association under dry land and high-altitude conditions Francisco Espinoza-Montes1,2,4, Wilfredo Nuñez-Rojas1, Iraida Ortiz-Guizado3, David Choque-Quispe2 RESUMEN Se experimentó el cultivo asociado de avena (Avena sativa) y vicia común (Vicia sativa) en condiciones de secano, a 4035 m sobre el nivel del mar, para conocer su comportamiento y efectos en el rendimiento, calidad de forraje y competencia interespecífica. En promedio, el rendimiento de forraje verde, materia seca y calidad de forraje fueron superiores al del monocultivo de avena (p<0.05). El porcentaje de proteína cruda se incrementó en la medida que creció la proporción de vicia común en la asocia- ción, acompañado de una disminución del contenido de fibra. En cuanto a los índices de competencia, el cultivo asociado de avena con vicia favorece el rendimiento relativo total de forraje (LERtotal>1). Ninguna de las especies manifestó comportamiento agresivo (A=0). Se observó mayor capacidad competitiva de la vicia común (CR>1) comparado con la capacidad competitiva de la avena. Palabras clave: cultivo asociado; rendimiento; calidad de forraje; competencia interespecífica ABSTRACT The oats (Avena sativa) and common vetch (Vicia sativa) cultivated in association was evaluated under dry land conditions at 4035 m above sea level to determine its performance and effects on yield, forage quality and interspecific competition. -

Revija Prirodoslovnega Muzeja Slovenije 2021 at the Occasion of the 100Th Issue of Scopolia

100 2021 PRIRODOSLOVNI MUZEJ SLOVENIJE MUSEUM HISTORIAE NATURALIS SLOVENIAE Vsebina / Contents: 200 let Prirodoslovnega muzeja I 200 years of the Natural History Museum I Janez GREGORI, Boris KRYŠTUFEK SCOPOLIA Ob stoti številki revije Scopolia Revija Prirodoslovnega muzeja Slovenije 2021 At the occasion of the 100th issue of Scopolia . 7 Journal of the Slovenian Museum of Natural History 100 Breda ČINČ JUHANT 200 let Prirodoslovnega muzeja Slovenije v 100. številki revije Scopolia Two centuries of the Slovenian Museum of Natural History in the 100th issue of Scopolia . 13 Matija KRIŽNAR Zgodovina in razvoj muzejskega naravoslovja do osamosvojitve Prirodoslovnega muzeja leta 1944 History and development of the natural science in the Museum of Natural History until its independency in 1944 . .17 years / 200 Natural the History of Museum I Breda ČINČ JUHANT Prirodoslovni muzej Slovenije po letu 1944 Slovenian Museum of Natural History since 1944 . 127 200 let Prirodoslovnega 200 let muzeja I : ) 2021 ( SCOPOLIA No. 100 100 SCOPOLIA No. ISSN 03510077 SCOPOLIA SCOPOLIA 100 2021 SCOPOLIA 100/2021 ISSN 03510077 Glasilo Prirodoslovnega muzeja Slovenije, Ljubljana / Journal of the Slovenian Museum of Natural History, Ljubljana Izdajatelj / Publisher: Prirodoslovni muzej Slovenije, Ljubljana, Slovenija / Slovenian Museum of Natural History, Ljubljana, Slovenia Sofi nancirata/ Subsidised by: Ministrstvo za kulturo in Javna agencija za raziskovalno dejavnost Republike Slovenije. / Ministry of Culture and Slovenian Research Agency Urednik / Editor-in-Chief: Boris KRYŠTUFEK Uredniški odbor / Editorial Board: Breda ČINČ-JUHANT, Igor DAKSKOBLER, Janez GREGORI, Franc JANŽEKOVIČ, Mitja KALIGARIČ, Milorad MRAKOVČIĆ (HR), Jane REED (GB), Ignac SIVEC, Kazimir TARMAN, Nikola TVRTKOVIĆ (HR), Al VREZEC Naslov uredništva in uprave / Address of the Editorial Offi ce and Administration: Prirodoslovni muzej Slovenije, Prešernova 20, p.p. -

Comandra Blister Rust Mary W

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1310 May, 2009 Comandra Blister Rust Mary W. Olsen Comandra blister rust is a native disease in Arizona on ponderosa pine. It also occurs on Mondell pine, a pine species introduced for landscapes and Christmas tree production in Arizona. Comandra blister rust can cause death of ponderosa saplings, but it is not an important disease of mature ponderosa trees. However, infections kill Mondell pine, and they should not be planted within a mile of Comandra. The alternate host for the rust is Comandra pallida, for which the disease is named. Comandra pallida, commonly called bastard toadflax, is a small herbaceous perennial plant found in close association with oak. It has small light pink flowers in terminal clusters and nutlike fruit. It is found throughout Arizona at elevations of 4,000- 8,000 ft. Pathogen: Comandra blister rust, Cronartium comandrae Hosts: Pinus eldarica (Mondell pine, Afghan pine), Pinus ponderosa (ponderosa pine) and Comandra pallida, bastard toadflax Symptoms/signs: Comandra blister rust on Mondell pine. On Mondell pine, Comandra blister rust causes branch dieback and death of trees of all ages. Swollen areas produced on the alternate host, Comandra. These are develop in branches and trunks, and the bark and delicate spores that can travel in air currents only about underlying sapwood die. On pine, orange “blisters” one mile. During the first year, the fungus becomes develop on trunks and branches as the bark splits and established in pine bark, and swollen areas with fruiting ruptures. Infections on Comandra, the alternate host, structures (spermagonia) develop in branches and appear as orange or rusty colored pustules on leaves trunks. -

Davis Expedition Fund Report on Expedition / Project

DAVIS EXPEDITION FUND REPORT ON EXPEDITION / PROJECT Expedition/Project Title: Biogeography and Systematics of South American Vicia (Leguminosae) Travel Dates: 28/09/2010 – 12/11/2010 Location: Northern Chile and northern Argentina Group Members: Paulina Hechenleitner Collection of research material of Vicia in the form of Aims: herbarium specimens, habitat data, digital images, silica- dried leaf samples, and base-line data on the IUCN conservation status of Vicia. Outcome (not less than 300 words):- See attached report. Report for the Davis Expedition Fund Biogeography and Systematics of South American Vicia (Leguminosae) Botanical fieldwork to northern Chile and northern Argentina 28th of Sep to 12th of November 2010 Paulina Hechenleitner January 2011 Introduction Vicia is one of five genera in tribe Fabeae, and contains some of humanity's oldest crop plants, and is thus of great economic importance. The genus contains around 160 spp. (Lewis et al. 2005) distributed throughout temperate regions of the northern hemisphere and in temperate S America. Its main centre of diversity is the Mediterranean with smaller centres in North and South America (Kupicha, 1976). The South American species are least known taxonomically. Vicia, together with Lathyrus and a number of other temperate plant genera share an anti- tropical disjunct distribution. This biogeographical pattern is intriguing (Raven, 1963): were the tropics bridged by long distance dispersal between the temperate regions of the hemispheres, or were once continuous distributions through the tropics severed in a vicariance event? Do the similar patterns seen in other genera reflect similar scenarios or does the anti-tropical distribution arise in many different ways? The parallels in distribution, species numbers and ecology between Lathyrus and Vicia are particularly striking.