Full Report (PDF 415

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

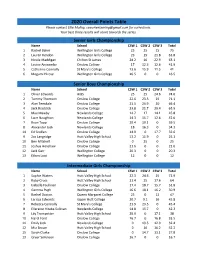

2020 Overall Points Table Please Contact Ellie Molloy, [email protected] for Corrections

2020 Overall Points Table Please contact Ellie Molloy, [email protected] for corrections. Your best three results will count towards the series. Senior Girls Championship Name School CSW 1 CSW 2 CSW 3 Total 1 Rachel Baker Wellington Girls College 25 25 25 75 2 Lauren Kendon Wellington Girls College 23 19 21.8 63.8 3 Nicole Maddigan Chilton St James 24.2 16 22.9 63.1 4 Louise Anscombe Onslow College 17 12.3 12.6 41.9 5 Catherine Connolly St Mary's College 13.6 15.9 11.5 41 6 Megumi Hirose Wellington Girls College 16.5 0 0 16.5 Senior Boys Championship Name School CSW 1 CSW 2 CSW 3 Total 1 Oliver Edwards HIBS 25 25 24.6 74.6 2 Tommy Thomson Onslow College 22.6 23.5 25 71.1 3 Alan Teesdale Onslow College 21.5 24.9 20 66.4 4 Jack Braddick Onslow College 23.8 21.7 20.4 65.9 5 Max Mawby Newlands College 14.7 17 14.1 45.8 6 Liam Naughton Newlands College 14.3 15.7 12.6 42.6 7 Ryan Topp Onslow College 20.4 19.1 0 39.5 8 Alexander Jack Newlands College 18 16.3 0 34.3 14 Ed Sindlen Onslow College 14.9 0 17.7 32.6 9 Zac Langridge Hutt Valley High School 13.2 11.9 0 25.1 10 Ben Mitchell Onslow College 0 25 0 25 11 Joshua Henshaw Onslow College 21.6 0 0 21.6 12 Jack Garr Wellington College 20.3 0 0 20.3 13 Ethan Looi Wellington College 12 0 0 12 Intermediate Girls Championship Name School CSW 1 CSW 2 CSW 3 Total 1 Sophie Waters Hutt Valley High School 22.3 24.6 25 71.9 2 Ruby Cross Hutt Valley High School 21.4 25 17.6 64 3 Isabelle Faulkner Onslow College 17.4 18.7 15.7 51.8 4 Gemma Pugh Wellington Girls College 16.6 18.1 16.2 50.9 5 Rachel -

Nau Mai, Haere Mai

DECEMBER 2018 | TERM 4 Founded 1959 Photo courtesy of Tim Plant Onehunga Community News Michael French 13Gr, Zoe Forrest 13Gr, Lesley Ly 13Wn, Matthew Moran 13Mm, Zane Neki 13Ed, Jacob Ngan-Sue 13Wn, Cerys Purnell 13Wn and Sophia Wells 13Gr. Nau mai, haere mai. This year, more than any I am aware of in awards. Because our students take such the history of Onehunga High School, our diverse academic pathways, it can be students have contributed their voices to difficult to compare NCEA achievement considerable positive change for current fairly between students when they have and future students. not yet completed their year’s assessments. Our community and our staff have So, 2018 is the first year of a new approach. also contributed to this, of course, At our awards ceremony, we acknowledged with initiatives including inquiry many students for wonderful achievement. projects beginning in the junior school, We did not name the Dux and Proxime the Fakatoukatea Tongan Leadership Accessit. Rather, we acknowledged students programme, and the launch of the partnership whose achievement to date makes them the between Fonterra and our Business School. top potential candidates for these awards. There is more to come, and that is one of the We will award these two top academic awards many things that continues to excite about at our Onehunga High School Scholarship our school and our community; we are ever assembly in 2019, based on confirmed learning and ever growing. assessment results. One of the changes this year, is in the This year the Prime Minister announced the awarding of our most prestigious academic beginning of our long awaited rebuild. -

Informer March 2020.Indd

ISSUE 1 |MARCH 2020 DEAR PARENTS AND GUARDIANS IT IS MY GREAT PLEASURE TO PRESENT TO YOU, THE FIRST NEWSLETTER FOR 2020. WE HAVE MADE A SUPERB START IN OUR SIXTYFIRST YEAR AS A SCHOOL; WITH A RECORD ROLL, SOME IMPRESSIVE EXAMINATION RESULTS AND A NUMBER OF EXCITING INNOVATIONS AND INITIATIVES BEFORE US, OVER THE NEXT TWELVE MONTHS. Confi dence in the school is obviously years, with 44% of our students gaining strong. Our roll is the highest that it has a cer fi cate endorsed with Merit or been in the school’s history, with 751 Excellence and 80% qualifying for students (up from 744 in 2019 and 722 in University Entrance. At Level Two, 94% 2018). We have started the year with a gained their na onal cer fi cate, with Grant Lander Year 9 cohort of 130 students and with our 47% gaining either a Merit or Excellence HEADMASTER biggest ever number of female students endorsement. While at Level One, 94% – 151. Encouragingly we con nue to gained their cer fi cate and for 60% this operate with small average class sizes at was endorsed with Merit or Excellence. Barrier Island. Our 1st XI cricket side each of the Year levels: with 18 in Year 9, In Cambridge examina ons, we had defeated a strong Auckland Division 1A, 19 in Year 10 core classes, 15.7 in Year 11, 100% pass rate for IGCSE Chemistry, Mt Albert Grammar in two fi xtures. While 14.7 in Year 12 and an average of 12.7 in English and Mathema cs and 100% for AS our rowers made 13 A fi nals and seven Year 13 op on classes. -

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Week 10, Term 3 2017

Weekly Newsletter 27 September 2017 I orea te tuatara ka patu ki waho - a problem is solved by continuing to find solutions Term 3 - Issue 10 Important Dates From The Principal’s Desk Wednesday 27 September Anniversary progress reports Kia ora, Nameste, Talofa, Konnichiwa, Guten Tag , Gidday, Vannakkam, ni Hao, Kia orana, Hola, come home for year 1-3 students Salam, Sa wat dee kha, Dia Dhuit, Goeie Dag, Bonjour, Hello, (please let us know the greeting in your due these NZSL language if it is not here Thursday 28 September School Production at Newlands Production fever has taken hold. You child/ren are starring in ‘The Magic of Bellevue’ at College Hall - 1:00pm + 6:30pm Newlands College tomorrow - in both the matinee and the evening show. There are tickets still Last day for Calendar orders available for the afternoon matinee and a few tickets left for the evening performance so make sure that you do not miss out on this amazing entertainment tomorrow. Friday 29 September Last day for Sileni Wine orders As this is the final newsletter at the end of a very busy term, I would like to take this Last day of Term 3 opportunity to thank our incredible staff for all their hard work to support your child/ren’s Monday 16 October First day of Term 4 learning and growth this term. The Jubilee projects, powhiri and performances were a credit to Monday 30 October - Dental Van visiting school our children and the adults who helped them. The Artsplash performance was too. The office Friday 24 November work involved in Jubilee, fundraising and ticket sales is some of the ‘behind the scenes’ work that is extra work that is often taken for granted. -

College Sport Wellington Secondary Schools Cross Country Champs 2018 Wednesday 30Th May 2018 Harcourt Park, Upper Hutt

College Sport Wellington Secondary Schools Cross Country Champs 2018 Wednesday 30th May 2018 Harcourt Park, Upper Hutt AWD - Boys (ID) Race distance: 2km Start time: 12:30pm Individual Results Placing Race # Name School Time 1 27 Josh TAYLOR Wairarapa College 0:09:08 2 4 Maurice BERRINGTON GRUMBALL Upper Hutt College 0:09:20 3 1 David ANAS Rongotai College 0:11:26 4 20 Nicholas MCRAE Wairarapa College 0:11:45 5 17 Rohan Lane Turnbull Wellington High School 0:12:29 6 31 Daniel VORESARA Rongotai College 0:13:07 7 29 Kane TUHI Mana College 0:13:15 8 32 Aiden WARRINGTON Rongotai College 0:13:34 9 21 Kesh MISTRY Rongotai College 0:13:37 10 28 Lachlan THOMSON Mana College 0:14:09 11 19 George LIVINGSTONE Rongotai College 0:14:15 12 14 Niall KANE Rongotai College 0:14:30 13 6 Harrison BULL-ELVINES Upper Hutt College 0:15:14 14 13 Gabriel JOHNS Mana College 0:15:38 15 26 Ben TAYLOR Wairarapa College 0:16:26 16 18 Michael LANGLEY Upper Hutt College 0:16:50 17 22 Milan PAVLOVIC Rongotai College 0:16:51 18 12 Hayden GARRETT Mana College 0:17:47 19 34 Leo James (LJ) WILLIAMS Mana College 0:18:24 20 5 Gabriel BROUGHTON KINGI Mana College 0:19:12 21 15 Leo KELLY Onslow College 0:23:03 22 30 Jimmy UDOVENKO Mana College 0:26:48 Schools Team results - 3 person AWD - Boys (ID) Placing School Points 1 Rongotai College 17 2 Wairarapa College 20 3 Mana College 31 4 Upper Hutt College 31 Schools Team results - 6 person AWD - Boys (ID) Placing School Points 1 Rongotai College 49 2 Mana College 88 College Sport Wellington Secondary Schools Cross Country Champs -

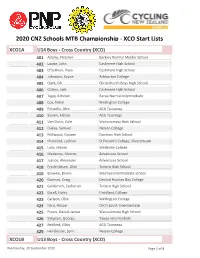

2020 CNZ Schools MTB Championship - XCO Start Lists

2020 CNZ Schools MTB Championship - XCO Start Lists XCO1A U14 Boys - Cross Country (XCO) 401 Adams, Fletcher Berkley Normal Middle School 402 Laurie, John Cashmere High School 403 O'Sullivan, Payo Cashmere High School 404 Johnston, Kayne Ashburton College 405 Clark, Oli Christchurch Boys High School 406 Collins, Jack Cashmere High School 407 Topp, Echelon Raroa Normal Intermediate 408 Cox, Nikhil Wellington College 409 Pengelly, Alex ACG Tauranga 410 Slaven, Kieran ACG Tauranga 411 Van Dunn, Cole Wainuiomata High School 412 Dukes, Samuel Nelson College 413 Millwood, Cooper Dunstan High School 414 Pitchford, Lachlan St Patrick's College, Silverstream 415 Lally, Nikolai Wellesley College 416 Medeiros, Marcos Adventure School 417 Justice, Alexander Adventure School 418 Fredericksen, Ollie Trident High School 419 Browne, Bruno Waimea Intermediate school 420 Gatman, Craig Central Hawkes Bay College 421 Goldsmith, Zacheriah Trident High School 422 Excell, Harry Fiordland College 423 Carlyon, Ollie Wellington College 424 Ford, Harper ChCh South Intermediate 425 Purvis, Daniel-James Wainuiomata High School 426 Simpson, George Taupo Intermediate 427 Bedford, Elliot ACG Tauranga 429 Henderson, Sam Nelson College XCO1B U13 Boys - Cross Country (XCO) Wednesday, 30 September 2020 Page 1 of 8 301 Turner, Mitchel Fernside School 302 Moir, Cam The Terrace School (Alexandra) 303 Dobson, Jakob St Mary's School (Mosgiel) 304 Malham, Lucas Waimea Intermediate school 305 Kennedy, Leo South Wellington Intermediate 306 Cameron, Louie Taupo Intermediate 307 -

Men's National Championship Records

MEN'S NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP RECORDS 1939 — 2013 THIRD EDITION — 2013 INTRODUCTION The following pages contain, as far as I can ascertain, the winners and runners-up of all Men's and Boys' New Zealand domestic competitions since the inception of our sport up until the completion of the most recent season. At this time I have not been able to document all runners-up prior to 1958, but hopefully some of that information will become available in due course. Remember, too, that between 1945 and 1949 the Beatty Cup was decided on a challenge basis. Earlier listings of the various championship winners have generally been assembled under a trophy banner, ie winners of the Beatty Cup or the Bensel Cup. While that method served the purpose admirably at the time, changes — notably sponsorship and different tournament formats — make that approach, in my opinion, more cumbersome. Many trophies were re-allocated and sometimes superceded, and on occasions reappeared in a different role, which sometimes made it difficult to follow just what competition/format they were being awarded to. I have therefore opted to list competitions continuously from the beginning until, in some cases, they were eventually discontinued altogether and note, as best I can, the various stages trophies were awarded or discarded. With most age-group categories I have added explanatory notes, which hopefully make clearer the evolution of the various grades. These days our "official records" largely ignore the days before Under-19, Under-17 and Under-15 grades, but I think it is important to ensure the records are maintained as accurately as possible right from the beginning of those grades which played such a huge part in building our sport in the '60s. -

High School Preparation Program That Prepares Students for Entry Into a New Zealand High School

KIWI ENGLISH ACADEMY HighHigh SchoolSchool PreparationPreparation Kiwi English Academy has a unique high school preparation program that prepares students for entry into a New Zealand high school. Since our separate high school campus opened in 1995 Kiwi English Academy has sent hundreds of students into high schools all around New Zealand. Programme Features A structured programme that includes General English plus subject-specific study once students have reached a certain level. Long-term students are encouraged to take Cambridge English for Schools test at the end of their programme. NZQA ( New Zealand Qualifications Authority) accredited programme – accredited to teach NCEA (National Certificate in Educational Achievement) unit standards in English, science, maths, accounting, economic theory and practice. Kiwi English Academy is one of the few English language schools in NZ that is accredited to offer these NCEA unit standards and the only school in central Auckland with this capability. Assessment methods linked to those at high school to ensure consistency for students. A disciplined environment where students are able to adjust academically, socially and personally to their new life in New Zealand. A mix of nationalities. Our junior programme attracts students from many different countries including Bra- zil, China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, New Caledonia Russia, Taiwan, Turkey and Vietnam. Students have the opportunity to make friends from around the world. Programme Length Support Services The length of the programme KiwiCare -

Read Our Thank You List

The Housing, Heating and Health Study would not have been possible without the help of many people and organisations and we would like to take the opportunity here to thank: Our community partners: Tu Kotahi Maori Asthma Trust, Waiwhetu Marae and Community Planners in the Hutt Valley, Porirua Health Plus and Te Ropu Awhina in Porirua. Pacific Trust Canterbury, Community and Public Health and Te Amorangi Richmond in Christchurch, The Otago Asthma Society in Dunedin and Te Runaka O Awarua in Bluff. Our insulation retrofitters and heater suppliers and installers: Energy Smart, Community Energy Action and Kati Huirapa Runaka ki Puketeraki who supplied and installed each house with insulation, Air Con (using Fujitsu and Mitsubishi products) who installed the heat pumps, Solid Energy who installed the Wood Pellet Burners and Hutt Gas and Plumbing who installed the Flued Gas Heaters. Thank you also to Smart Power who managed the tender and installation process. The energy companies, that supplied household energy data Contact Energy, Genesis Energy, Meridian Energy, Empower and Trustpower. General practitioners, who supplied data on patient visits Avalon Medical Centre, Acheson Avenue Community Health Centre, Aurora Health Centre, Barrington Medical Centre, Belfast Medical Centre, Bluff Medical Centre, Broadway Medical Centre Dunedin Ltd, Capital Care Health Centre, Cashmere Medical Practice, Caversham Medical Centre, Christchurch Family Clinic, Christchurch South Health Centre, Community Support Medical Centre, Corpore Sano Ltd. Surgery, Doctors on Riccarton, Dr A.E.J.Fitchett, Dr Andrew Campbell Smillie, Dr Asha Lata Sai, Dr Astrid Windfuhr, Dr D. Ritchie Consulting Rooms, Dr G.V.A. de Croos, Dr H.T. -

Waka Ama Assoc RSS - Waka Ama Sprints 1

Hoe Tonga Pacifica Waka ama Assoc RSS - Waka ama Sprints 1 W1 Heats 001 Boys U16 - W1 250m Heat 1/2 (8 ) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 TULEPU, Turi Tawa 2 HEKE, Areiteuru WRM Te Rito 3 BROOKING, Elijah Tawa 4 SMITH, Olliver Newlands 002 Boys U16 - W1 250m Heat 2/2 (8) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 DOYLE, Te Aranui WRM Te Rito 2 HYNES, John Paraparaumu 3 KAPPELY, Harlem Rongotai 4 TE PAA, Tyran Tawa 003 Boys U19 - W1 250m Heat 1/1 (5) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 KIDWELL - JARVIS, Rakaunui WRM Te Rito 2 MURAAHI, Logan Otaki 3 DEVITT, Levi Rongotai 4 ROPATA, Wiremu WRM Te Rito 5 TAMAKEHU , Wade TKKM o Tupoho 004 Girls U16 - W1 250m Heat 1/1 (3 ) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 ROA, Potiki WRM Te Rito 2 COMERFORD, Lana Upper Hutt 3 KIEL, Ariana WRM Te Rito 4 005 Girls U19 - W1 250m Heat 1/1 (3) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 GOODHEW, Monique Otaki 2 ELKINGTON, Huitau Otaki 3 4 Saturday 9 March 2013 Onepoto, Porirua Hoe Tonga Pacifica Waka ama Assoc RSS - Waka ama Sprints 2 W6 Heats 006 Boys U16 - W6 500m Fun Race 1/3 (10 teams) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 Mana College Mana 2 KAPUMANAWAWHITI WRM Te Rito 3 RC Ngake 250 Rongotai 4 RC Whataitai 250 Rongotai 007 Boys U16 - W6 500m Fun Race 2/3 (10 teams) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 RC Whataitai 500 Rongotai 2 Hukatai Te Kura Porirua 3 Tawa College Sons of Lucas Tawa 4 008 Boys U16 - W6 500m Fun Race 3/3 (10 teams) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 RC Ngake 500 Rongotai 2 St Patrick's College, Silverstream Silverstream 3 Tawa College Do Justly Boyz Tawa 4 009 Boys U19 - W6 500m Fun Race 1/3 (10 teams) Lane Team School / Club Place Time 1 RC Tangi te Keo 500 Rongotai 2 MAIOTAKI WRM Te Rito 3 Wellington College Well. -

Ministry of Health Contracted Adolescent Dental Providers

Ministry of Health Contracted Adolescent Dental Providers Wellington Capital Dental Whai Oranga Newtown 125-129 Riddiford Street Dental - Cuc Dang 7 The Strand, Wainuiomata Angela McKeefry Level 3, The Dominion 389 8880 564 6966 473 7802 Bldg, 78 Victoria Street Newtown Newtown Dental Jaideep Ben Catherwood Surgery Vijayasenan 1st Level 90 The Terrace 100 Riddiford Street 11 Queen Street, 472 3510 **(existing patients 389 3808 Wainuiomata Capital Dental The only) Ground Floor, Montreaux Adrian Tong Raine Street Dental, 4 Wellington CityWellington Terrace 939 9917 Building, 164 The Terrace 476 7295 Raine Street 499 9360 Karori Lumino Dental 180 Stokes Valley Road, Karori Dental 939 1818 Stokes Valley Dental Awareness Level 1, 9 Marion Street Centre 146 Karori Road 385 4386 Ashwin Magan 476 6451 Level 3, 84-90 Main Street Earle Kirton Harbour City Tower, 29 527 7914 Singleton Dental 473 7632 Brandon Street 294A Karori Road Christopher Allan 476 6252 U UUUU 22 Royal Street Irina Kvatch Central Dental Surgery, 139 Upper Hutt 528 5302 CODE Dental 220 Main Road 472 6306 Featherston Street Art of Dentistry 10 Royal Street 232 8001 Tawa 527 9437 Joanna Ora Toa Medical Hodgkinson Level 1, 90 The Terrace Michael Walton Centre 178 Bedford Street 22 Royal Street 472 3510 528 5302 237 5152 Navin Vithal Tennyson Dental Centre, Porirua Lumino Silverstream Village Shop The Dental Centre 801 6228 32 Lorne Street, Te Aro Silverstream 14/Cnr Whitemans Rd & Porirua 4 Lydney Place Peter Scott 528 3984 Kiln St 29 Brandon Street 237 6148 473 7632 Walter Szeto