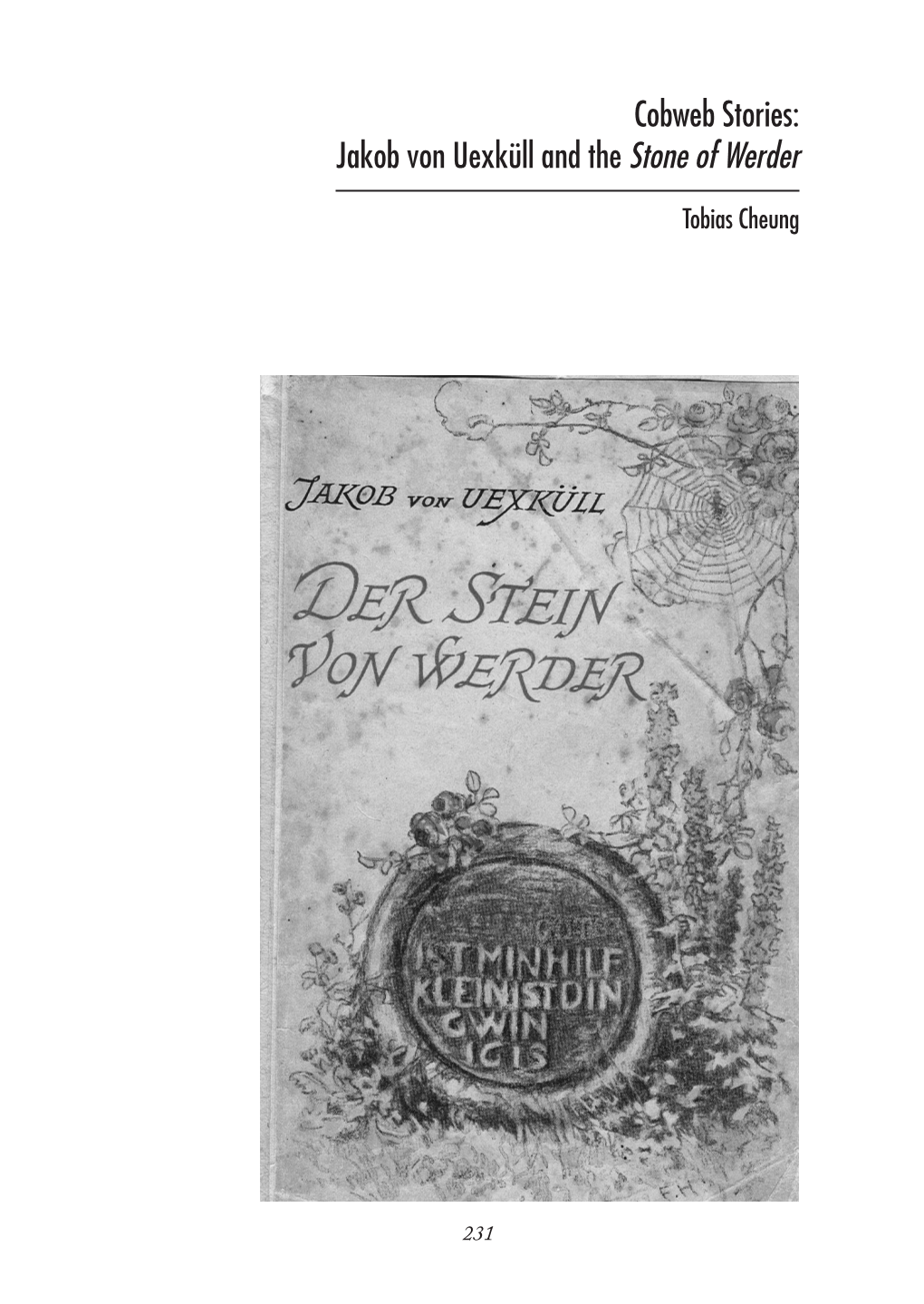

Cobweb Stories: Jakob Von Uexküll and the Stone of Werder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Creative Misunderstanding: Ludwig Binswanger

Four A Creative Misunderstanding: Ludwig Binswanger No discourse on the exchange of ideas between Freudian psychoanalysis and philosophical phenomenology would be complete without mentioning the works of psychiatrist, Dr. Ludwig Binswanger. As a one-time mentor to Medard Boss, an acquaintance of Martin Heidegger, and a close friend to Sigmund Freud, Binswanger was thoroughly immersed within the historical context of the time. His continued loyalty to Freud as well as his interest in Husserlian and Heideggerian phenomenology make him an especially pivotal figure in the early intersection between these two domains. Unlike many of the intellectuals who fervently opposed Freudian psychoanalysis, Binswanger never entirely rejected the importance of Freud’s work. He considered Freud’s metapsychology to be a success within the limits of scientific theory, and praised its contributions for offering a thorough and complete description of homo natura. However, Binswanger also contended that Freud’s depiction of humans as “primal” was not “the source and fount of human history,” but rather “a requirement of natural-scientific research.”1 Here, Heidegger’s philosophy was ideal in demonstrating the limitations of science when practically applied to the realm of human inquiry. His phenomenological approach also offered a means for expanding beyond science in order to understand the whole person in an effort to create a more holistic therapeutic approach. Early on, (c. 1922–7) Binswanger believed that it was Husserlian phenomenology that could provide the proper method for therapy. With the publication of Being and Time in 1927, Binswanger, without entirely abandoning Husserl, modified this somewhat when he suggested that it was Heidegger’s ontology from which “existential analysis received its decisive stimulation, its philosophical foundation and justification, as well as its methodological directives.”2 Binswanger was particularly struck by Heidegger’s critique of science as well as his elaboration of the universal and fundamental structures of human Dasein. -

Language Evolution: What We Need I.) the Merkwelt Ii.) the Umwelt

What we need • Language evolution theories need to be: – Evolutionarily plausible: Consistent with fossil Language Evolution: and archeological record; with knowledge of our ancestor’s lives and structure – Consistent with what we know about language Neurological, cognitive, social? – Consistent with what we know about anatomy, including neuroanatomy MU! – Computationally plausible: Consistent with some functional understanding of language Symbols as representational flexibility Symbols as representational flexibility • As we have been discussing, symbolism is a • Insofar as this is true, language evolution may be way of increasing representational underlain by many non-linguistic incremental adaptations, each of which introduces a (perhaps very flexibility (of removing stimuli [‘goads’] slight) increase in freedom in representation: in the from the environment, and bringing them number of ways we can look at things inside) • Anything that helps us look at things in a new way (modulates our behavioral pesponses) increases • Representational flexibility may be useful in potential adaptivity AND also brings us closer to ‘true’ many many ways, many of which are not symbolism linguistic per se i.) The Merkwelt ii.) The Umwelt • A factor that is tied in more directly to representational flexibility • Jakob von Uexkull (1934): A Stroll through the Worlds of is the ability to detect those stimuli that can be used for adaptive Animals and Men: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds. purposes (the size of the creature's Umwelt, [German for environment] -

The Miller Umwelt Assessment Scale: a Tool for Planning Interventions for Children on the Autism Spectrum Sonia Mastrangelo*

: Open A sm cc ti e u s s A Autism - Open Access Mastrangelo S, Autism-Open Access 2015, 5:2 DOI: 10.4172/2165-7890.1000140 ISSN: 2165-7890 Research Article open access The Miller Umwelt Assessment Scale: A Tool for Planning Interventions for Children on the Autism Spectrum Sonia Mastrangelo* Lake head University Orillia, Lake head University Orillia, Faculty of Education ,500 University Avenue, Orillia, Ontario, Canada *Corresponding author: Sonia Mastrangelo, Lake head University Orillia, Lake head University Orillia, Faculty of Education ,500 University Avenue, Orillia, Ontario, Canada, Tel:(705) 330-4008 x. 2635; E-mail: [email protected] Rec Date: April 10, 2015; Acc Date: April 16, 2015; Pub Date: April 22, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Mastrangelo S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The Miller Umwelt Assessment Scale is a useful tool for obtaining information about the developmental capacities of children on the autism spectrum. The assessment, made up of 19 tasks in the areas of: body organization, contact with surroundings, expressive and receptive communication, representation, and social-emotional development, has been used with much success over the past 40 years. While many assessments are difficult to administer to children on the autism spectrum, the simplicity of the MUAS reveals key strengths and challenges for both low and high functioning children on the spectrum. The results guide parents and clinicians in providing a curriculum and/or home program that moves children up the developmental ladder. -

Parallel Session 27: Cultural Differences in Public Understanding of Sciences

8th International Conference on Public Communication of Science and Technology (PCST), Barcelona, Spain, 3-6 June 2004 Parallel Session 27: Cultural Differences in Public Understanding of Sciences FRAMING AS A THEORY FOR THE COMMUNICATION OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Urs Dahinden University of Zurich, Switzerland, E-mail: u.dahinden@ ipmz.unizh.ch Keywords: theoretical framework, media, public opinion, framing, content analysis, survey, international comparison, biotechnology, Text Science and technology are issues that receive increasing attention in mass media (Dahinden. 2002). However, the analysis of this media coverage is often done with little or no theoretical background at all. Framing provides a promising theoretical framework that can fill this gap. In the past several years, the framing approach has received increasing interest in communication studies (Reese. 2001) and also other social science disciplines like sociology, psychology or in political science. Despite the relative success of the concept, there is no agreed-on definition of what framing as a process or frames as results of such processes might be. Nevertheless, the following definition by Entman (1993) can be considered as a least common denominator of the various efforts to define the term: “To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such away as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation” (Entman. 1993: 52). This definition highlights that frames are not issues, but background patterns of interpretation that structure the perception and evaluation of a specific issue. Based on that definition, public debates can be described as framing contests between competing actors that try to frame an issue according to their own point of view (Pan. -

Axiomatizing Umwelt Normativity

Sign Systems Studies 39(1), 2011 Axiomatizing umwelt normativity Marc Champagne Department of Philosophy, York University 4700 Keele, Toronto, Canada M3J 1P3 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Prompted by the thesis that an organism’s umwelt possesses not just a descriptive dimension, but a normative one as well, some have sought to annex semiotics with ethics. Yet the pronouncements made in this vein have consisted mainly in rehearsing accepted moral intuitions, and have failed to concretely fur- ther our knowledge of why or how a creature comes to order objects in its environ- ment in accordance with axiological charges of value or disvalue. For want of a more explicit account, theorists writing on the topic have relied almost exclusively on semiotic insights about perception originally designed as part of a sophisti- cated refutation of idealism. The end result, which has been a form of direct given- ness, has thus been far from convincing. In an effort to bring substance to the right-headed suggestion that values are rooted in the biological and conform to species-specific requirements, we present a novel conception that strives to make explicit the elemental structure underlying umwelt normativity. Building and expanding on the seminal work of Ayn Rand in metaethics, we describe values as an intertwined lattice which takes a creature’s own embodied life as its ultimate standard; and endeavour to show how, from this, all subsequent valuations can in principle be determined. 10 Marc Champagne No animal will ever leave its Umwelt space, the center of which is the animal itself. (Jakob von Uexküll 2001[1936]: 109) I wished to find a warrant for being. -

The Melody of Life. Merleau-Ponty, Reader of Jacob Von Uexküll 353

Investigaciones Fenomenológicas, vol. Monográfico 4/I (2013): Razón y vida, 351-360. e-ISSN: 1885-1088 THE MELODY OF LIFE. MERLEAU-PONTY, READER OF JACOB VON UEXKÜLL LA MELODÍA DE LA VIDA. MERLEAU-PONTY, LECTOR DE JACOB VON UEXKÜLL Luís António Umbelino Associação Portuguesa de Filosofia Fenomenológica (APFFEN)/ Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal [email protected] Abstract: This paper aims to meditate on the Resumen: Este artículo trata de meditar acerca importance of Jacob von Uexküll’s notion of de la importancia de la noción de Umwelt de Umwelt in Merleau-Ponty’s research of an onto- Uexküll en la búsqueda de un camino onto- phenomenological path - that is to say, in Mer- fenomenológico por parte de Merleau-Ponty, es leau-Ponty’s putting to the test of some of the decir, en la puesta a prueba de ciertas tesis y thesis and presuppositions that were at the presupuestos que estaban presentes en el heart of both La structure du Comportement núcleo tanto de La structure du Comportement and the Phénoménologie de la perception. As como de Phénoménologie de la perception. Merleau-Ponty is looking for a way to develop Siendo así que Merleau-Ponty persigue encon- and overcome the results of an investigation trar un camino para desarrollar y superar los based on the point of view of consciousness, resultados de una investigación basada en el this notion of Umwelt will become – namely in punto de vista de la conciencia, esta noción de the three lecture courses on the concept of Umwelt llegará a ser –especialmente en las Nature, delivered by Merleau-Ponty in the late lecciones de los tres cursos sobre el concepto 1950s at the Collège de France – more and de Nature, impartidos por Merleau-Ponty a more decisive. -

The Theory of Meaning*

The Theory of Meaning* JAKOB VON UEXKÜLL Introduction to the first edition The materialists pull everything down from the sky and out of the invisible world onto the earth as if they wanted to clench rocks and oak trees in their fists. They grasp them, and stubbornly main- tain that the only objects that exist are those that are tangible and comprehensi- ble. They believe that the physical exis- tence of an object is existence itself, and look down smugly on other people — those who acknowledge another area of existence separate from the physical. But they are totally unwilling to listen to another point of view. (Plato, Sophisles) An excellent researcher and director of an Institute for Biology who is correctly held in high regard has blamed me for misleading the public. His reproach should not be taken lightly. As far as I can understand his criticism, he states that my theory of the orderly arrangement of nature stirred up vain hopes among my many readers. I have previously been accused of deception, but under different circumstances. On the isle of Ischia, where I spent a few beautiful spring days, I met an old acquaintance who asked for directions. I told him to turn left at the flowering rose bush. Somewhat later, we met each other at said rose bush. My acquaintance accused me of having misled him because he said that the rose bush was not in bloom. I then discovered that he was color-blind, and could not see the red roses against the green of the leaves. -

An Introduction to Umwelt*

An introduction to Umwelt* JAKOB VON UEXKUÈ LL Everyone who looks about in Nature ®nds himself (or herself ) in the center of a circular island that is covered by the blue vault of heaven. This is the perceptible world that has been given to us, it contains everything we can see. And the visible things are ordered according to their signi®cance for our life. Everything that is near to us, and has immediate impact on human beings, is there in full size; distant and hence less dangerous things appear small. The movements of the small things may be invisible, while the movements of the things that are close, scare us. When we lie in the shadow of a tree, we are not aware of the imperceptible march of the shadow that is caused by the transit of the distant sun. But every movement of the leaves, caused by the wind or by a bird, is clearly manifested in the shadow outlines. Things that are invisible to Man because they are concealed by other objects, are revealed to his ear by their sound or to his nose by their smell and, if they come very close, to his sense of touch. Around us is a protective wall of senses that gets denser and denser. Outward from the body, the senses of touch, smell, hearing and sight enfold man like four envelopes of an increasingly sheer garment. This island of the senses, that wraps every man like a garment, we call his Umwelt. It separates into distinct sensory spheres, that become manifest one after the other at the approach of an object. -

THE MINIMAL EPISTEMOLOGICAL and ONTOLOGICAL CONDITIONS for a THEORY of SYSTEMIC INTERDISCIPLINARITY the Notion of Interdisciplin

Philosophica 48 (1991, 2) pp. 57-74 THE MINIMAL EPISTEMOLOGICAL AND ONTOLOGICAL CONDITIONS FOR A THEORY OF SYSTEMIC INTERDISCIPLINARITY Alexander 1. Argyros The notion of interdisciplinarity is infiltrating the academic world with breathtaking rapidity. Whether in the arts, the humanities, the social sciences, or even the natural sciences, there is a growing consensus that the traditional disciplinary boundaries are ill-adapted for the information rich world we are creating. And yet, despite a general acceptance of the necessity to move beyond traditional academic enclaves, there is nothing approaching consensus regarding the exact nature and scope of interdis ciplinary thought. It is indeed odd that so many scholars, researchers, scientists, and artists agree on a pressing need whose contours are left unexplicit and ill-defined. Perhaps the main reason for the vagueness of much discussion on the notion of interdisciplinarity is that there has as yet been little work done on the fundamental ontological and epistemological conditions for an interdisciplinary world view. In other words, I believe that although interest in interdisciplinarity is the herald of a major paradigm shift in Western philosophical thought, a shift whose effects are proliferating, its conditions of possibility remain largely unexplored. It is beyond the scope of this essay to present a coherent theory of interdisciplinarity. However, in the interests of beginning a discussion of the nature of interdisciplinar ity, I will attempt to outline a number of ontological and epistemological conditions which I believe are necessary for understanding interdisciplin arity. In general, there are two kinds of approaches to the question of inter disciplinarity. -

Leib, Umwelt E Arquitectura. Leituras De M. Merleau-‐‑Ponty E M. Richir

Luís António Umbelino | Leib, Umwelt e Arquitectura. Leituras de M. Merleau-Ponty e M. Richir Leib, Umwelt e Arquitectura. Leituras de M. Merleau-Ponty e M. Richir Luís António Umbelino (Universidade de Coimbra – Portugal) 1. O problema fenomenológico da arquitectura. Não será certamente de espantar que o vigoroso projecto de refundação do horizonte fenomenológico empreendido por Marc Richir atribua um lugar ao tema da arquitectura. A sua importância mede-se pelo conjunto de questões, difíceis mas decisivas, que mobiliza: a necessidade de investigar a aparição rebelde do próprio espaço1, de dilucidar o imbricamento originário do espaço e do tempo2, de meditar a articulação entre Leib e espaço3, de interrogar a condição fundamentalmente enigmática e onírica do ser-no-mundo4, ou de ponderar aprofundadamente o significado do habitar e do habitável5 sobre o pano de fundo da instituição simbólica que a arquitectura não deixa de ser. A problemática fenomenológica da arquitectura esboça, assim, um quadro teórico tão importante quanto complexo. E, segundo Richir, não são muitos os autores que nos ajudam a enfrentá-lo: Husserl, um pouco, Fink, Patŏcka, ou Merleau-Ponty se seguirmos pacientemente as suas indicações. Nesta ocasião interessa-nos ponderar, em particular, o que, nas meditações de Merleau-Ponty, M. Richir considera “linhas de investigação fecunda”6 para reflectir o tema da arquitectura. Nos textos que dedica a este tema, Richir parece-nos indicar, mais ou menos explicitamente, três dessas tais linhas: uma primeira estaria ligada à ideia de que o Leib está no espaço à maneira de um medidor-medido do mundo: “que o vidente seja visível – escreve Richir –, que o sentinte seja sensível, significa com efeito que o Leib é, como o disse Merleau-Ponty, ‘medidor universal’ (mesurant universel) do mundo, mas um medidor medido pelo mundo, em quiasma com o mundo”7; na esteira de Merleau-Ponty, seria, assim, proveitoso investigar o enigmático modo de mútua pertença que corpo e espaço desenrolam – ou, talvez melhor, que corpo e espaço incarnam8. -

Internationales Institut Für Umwelt Und Gesellschaft (IIUG) International Institute for Environment and Society Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin

Internationales Institut für Umwelt und Gesellschaft (IIUG) International Institute for Environment and Society Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin IIUG pre 86-2 POLITICAL ECOLOGY AND THE SOCIAL SCIENCES The State of the Art by Philip D. Lowe* and Wolfgang Rüdig** *Bartlett School of Architecture and Planning, University College, Wates House, 22 Gordon Street, London. In 1984 Visiting Fellow at IIUG. **Department of Science and Technology Policy, The University of Manchester, Manchester. To be published in: British Journal of Political Science IIUG, Potsdam er Str. 58, 1000 Berlin 30, Tel. 030 - 26 10 71 SUMMARY In this paper the authors take issue with a number of re search approaches which play a dominant role in the field of environmental sociology. The most important of them, the "value change" approach, has its limitations. It is always necessary to explain how values are created and sustained, and it is therefore not appropriate to regard them as inde pendent variables. The focus should rather be upon the ways in which resources are mobilised in pursuit of particular interests generated by the structural context; and the ways in which that context is maintained or transformed by the struggles which it facilitates. The authors argue for a revived case study approach supple mented by survey analysis of the general public and of en vironmental groups and their members. In the past, surveys have grossly neglected the situational context of environ mental attitudes and action. However, the case study approach is also beset by several shortcomings. Case studies will have to be guided by theoretical approaches which put the indi vidual case into a broader perspective. -

The Worldmaker's Umwelt: the Cognitive Space Between a Writer's

The Worldmaker’s Umwelt: The Cognitive Space between a Writer’s Library and the Publishing House1 Dirk Van Hulle Abstract This essay adds a genetic dimension to the narratological suggestion to consider mod- ernist authors’ inquiries into the human mind (for instance, by means of stream-of- consciousness techniques) as examinations of the so-called “extended” or “extensive” mind. In Joyce’s case, this inquiry takes shape in enactive cognition, which is to a large extent inspired by his own experience as a writer who thought on paper. The enactive cognition that characterises his creative process is not just the result of the interaction between an intelligent agent and the materiality of his manuscripts. It is also the result of the interaction with other elements in his environment, such as newspapers and books, his personal library, as well as publishing houses and critics. Joyce’s use of Wyndham Lewis’s criticism and the newspaper clippings about his “Work in Progress” serve as case studies to analyse this enactive genesis. In his essay “Re-Minding Modernism” (2011), David Herman suggests that we regard “storyworlds” as a staging ground for “procedures of Umwelt construc- tion” and modernist writers as “Umwelt researchers in [Jakob] von Uexküll’s sense – explorers of the lived, phenomenal worlds that emerge from, or are enacted through, the interplay between intelligent agents and their cultural as well as material circumstances”.2 The biologist Jakob von Uexküll, a contempo- rary of Joyce’s, coined the term “Umwelt”3 to denote an organism’s model of the 1 The research for this article was made possible with the support of the European Research Council (under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme [FP7/2007– 2013] / ERC grant agreement no.