ABSTRACT One Must Only Glance Upon Franz Zeyringer's 400-Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edouard Lalo Symphonie Espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Edouard Lalo Born January 27, 1823, Lille, France. Died April 22, 1892, Paris, France. Symphonie espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21 Lalo composed the Symphonie espagnole in 1874 for the violinist Pablo de Sarasate, who introduced the work in Paris on February 7, 1875. The score calls for solo violin and an orchestra consisting of two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, triangle, snare drum, harp, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty-one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lalo's Symphonie espagnole were given at the Auditorium Theatre on April 20 and 21, 1900, with Leopold Kramer as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Bizet's Carmen is often thought to have ignited the French fascination with all things Spanish, but Edouard Lalo got there first. His Symphonie espagnole—a Spanish symphony that's really more of a concerto—was premiered in Paris by the virtuoso Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate the month before Carmen opened at the Opéra-Comique. And although Carmen wasn't an immediate success (Bizet, who died shortly after the premiere, didn't live to see it achieve great popularity), the Symphonie espagnole quickly became an international hit. It's still Lalo's best-known piece by a wide margin, just as Carmeneventually became Bizet's signature work. Although the surname Lalo is of Spanish origin, Lalo came by his French first name (not to mention his middle names, Victoire Antoine) naturally. His family had been settled in Flanders and in northern France since the sixteenth century. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Sarasate.Pdf

2 SEMBLANZAS DE COMPOSITORES ESPAÑOLES 29 PABLO DE SARASATE 1844 -1908 Robin Stowell Catedrático de Música de la Universidad de Cardiff ablo de Sarasate fue un heredero espiritual de Nicolò Paganini, un artista elegante y do- tado para el espectáculo cuya facilidad y arte innatos y cuya aristocrática presencia es- P cénica lo convirtieron posiblemente en el más grande y más venerado violinista y com- positor español. Según los testimonios contemporáneos, su elegante pero sutil estilo interpre- tativo era único y su desenfadado virtuosismo difería radicalmente tanto del enfoque “clásico” y enormemente intelectual de la “escuela” rival alemana de Joseph Joachim y sus discípulos co- mo de la técnica más rigurosa y el sonido enérgico y vibrante del más joven Eugène Ysaÿe. Así, Sir George Henschel llegó hasta el extremo de señalar que la interpretación de Sarasate del Concierto para violín Op. 64 de Mendelssohn en el Festival del Bajo Rin de 1877 “fue pa- ra los oídos alemanes como una suerte de revelación, provocando un auténtico furor”. Sarasate introdujo distinción, encanto y refinamiento en el arte de la ejecución violinística y presentaba su música con magnetismo, una facilidad y elegancia naturales y ningún tipo de afectación, hasta el punto de que su público encontraba irresistible su estilo “acariciante”. Su timbre solía describirse como dulce y puro, aunque no especialmente fuerte o vibrante, pero go- zó de un especial renombre por la precisión de su interpretación, la justeza de su afinación y, en palabras de Sir Alexander Mackenzie, su “talento para penetrar de forma intuitiva ‘debajo En «Semblanzas de compositores españoles» un especialista en musicología expone el perfil biográfico y artístico de un autor relevante en la historia de la música en España y analiza el contexto musical, social y cultural en el que desarrolló su obra. -

Bruno CANINO

Bruno CANINO Geboren in Neapel. Klavierstudium am Konservatorium in Neapel bei Vincenzo Vitale. Diplome für Klavier und Komposition bei Enzo Calace und Bruno Bettinelli in Mailand. Als Solist und Kammermusiker in den wichtigsten Konzertsälen und bei den wichtigsten Festivals in Europa, Amerika, Australien, Japan und China aufgetreten. Seit 40 Jahren Klavierduo mit Antonio Ballista und seit 30 Jahren Mitglied des „Trio di Milano“. Zusammenarbeit mit namhaften Künstlern wie Salvatore Accardo, Uto Ughi, Lynn Harrell, Itzhak Perlman, Victoria Mullova. Künstlerischer Leiter des Giovine Orchestra Genovese, des Campus Internazionale di Musica in Latina. Von 1999 bis 2001 Leiter der Abteilung Musik der Biennale Venedig. Widmet sich im Besonderen auch der zeitgenössischen Musik. Zusammenarbeit u. a. mit Pierre Boulez, Luciano Berio, Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, György Ligeti, Bruno Maderna, Luigi Nono und Sylvano Bussotti. Zahlreiche Uraufführungen. Unter der Leitung von Abbado, Muti, Chailly, Sawallisch, Berio und Boulez Auftritte mit Orchestern wie der Philharmonie der Mailänder Scala, Santa Cecilia in Rom, den Berliner Philharmonikern, der New York Philharmonie, dem Philadelphia Orchestra und dem französischen Nationalorchester. Leitung einer Meisterklasse für Klavier und Kammermusik am Berner Konservatorium. Zahlreiche Schallplatten- und CD-Aufnahmen wie z. B. Johann Sebastian Bachs „Goldberg Variationen“, das Gesamtwerk für Klavier von Alfredo Casella (Stradivarius). In Produktion das Gesamtwerk für Klavier von Claude Debussy. Als Schriftsteller 1997 Veröffentlichung von „Vademecum per il pianista da camera“ (ed Passigli). Born in Naples. Piano studies at the Conservatory of Naples with Vincenzo Vitale. Diplomas in piano and composition with Enzo Calace and Bruno Bettinelli in Milan. Performances as soloist and chamber musician in the most important concert halls and at the most important festivals in Europe, America, Australia, Japan and China. -

Wwciguide January 2019.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Renée Crown Public Media Center Dear Member, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Happy New Year! This month, we are excited to premiere the highly anticipated Chicago, Illinois 60625 third season of the period drama Victoria from MASTERPIECE. Continuing the story of Victoria’s rule over the largest empire the world has ever known, you will Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 meet fascinating new historical characters, including Laurence Fox (Inspector Member and Viewer Services Lewis) as the vainglorious Lord Palmerston, who crosses swords with the Queen (773) 509-1111 x 6 over British foreign policy. Websites Also on WTTW11, wttw.com/watch, and our video app this month, we know wttw.com you have been waiting for the return of Doc Martin. He’s back and the talk of wfmt.com the town is the wedding of the Portwenn police officer Joe Penhale and Janice Bone. On wttw.com, learn how the new season of Finding Your Roots uncovers Publisher Anne Gleason the ancestry of its subjects, and go behind the curtain for the first collaboration Art Director between Lyric Opera of Chicago and the Joffrey Ballet on their Orphée et Eurydice. Tom Peth WTTW Contributors On 98.7WFMT, wfmt.com/listen, and the WFMT app, the Metropolitan Opera Julia Maish on Saturday afternoons features Verdi’s Otello conducted by Gustavo Dudamel, Dan Soles WFMT Contributors Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur starring Anna Netrebko, Debussy’s enigmatic Pelléas Andrea Lamoreaux et Mélisande, and a new work by Nico Muhly based on Hitchcock’s filmMarnie . -

Download Booklet

95782 The cello concerto genre has a relatively short history. Before the 19th century, the only composers a few other works, including Monn’s fine, characterful Cello Concerto in G minor. Monn died of of stature who wrote such works were Vivaldi, C.P.E. Bach, Haydn and Boccherini. Considering the tuberculosis at the age of 33. problem inherent in the cello’s lower register, the potential difficulty of projecting its tone against Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) made phenomenal contributions to the history of the symphony, the weight of an orchestra, it is rather ironic that most of the great concertos for the instrument the string quartet, the piano sonata and the piano trio. He generally found concerto form less were composed later than the Baroque or Classical periods. The orchestra of these earlier periods stimulating to his creative imagination, but he did compose several fine examples. In 1961 the was smaller and lighter – a more accommodating accompaniment for the cello – whereas during unearthing of a set of parts for Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C major in Radenín Castle (now in the 19th century the symphony orchestra was significantly expanded, so that composers had to the Czech Republic) proved to be one of the most exciting discoveries in 20th-century musicology. take more care to avoid overwhelming the soloist. Probably dating from the early 1760s, the concerto is believed to have been composed for Joseph Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) composed several hundred concertos while employed as a violin Weigl, principal cellist of Haydn’s orchestra. This is the more rhythmically arresting of Haydn’s teacher (and, from 1716, as ‘maestro dei concerti’) at the Venetian girls’ orphanage known as authentic cello concertos. -

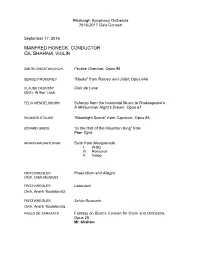

Program Notes by Dr

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

Sardinian Composers of Contemporary Music

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 12,2012 © PTPN & Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, Poznań 2012 CONSUELO GIGLIO Music Conservatory, Trapani Sardinian composers of contemporary music ABSTRACT: The meeting point between the school headed by Franco Oppo and the rich traditional music of the island gave birth in Sardinia to an intense flowering in the field of New Music, with a strong feeling of belonging and a constant call for a positive concept of identity. Thus, since the time of Oppo (1935) and his contemporary Vittorio Montis, we come across many composers that differ between each other but are almost always recognizably “Sardinian”. Oppo has been one of the most interesting figures on the international scene during the last few decades. After his studies in Rome, Venice and Poland in the early 1960s, he remained, by his own choice, in his home territory, sharing his “Sardinian-ness” in a free and dialectic manner with the avant-garde. After formulating his own particular aleatory approach, Oppo reached a turning point halfway through the 1970s: in Musica per chitarra e quartetto d’archi, Praxodia and, finally, in Anninnia I, the meeting point between avant-garde research and the special phonic quality of tra ditional music became more and more close-knit and organic, at the same time also acting on the founding language structure whilst still remaining under the control of incisive and informed dis ciplines (during the same period, moreover, he put forward new methodologies of analysis which were also necessary for his teaching). In this sense the most important works are chamber pieces like Anninnia I and II (1978, 1982), Attitidu (1983) and Sagra (1985), the theatrical work Eleonora d’Arborea (1986), some piano “transcriptions” - the Three berceuses (1982), Gallurese and Baroniese (1989; 1993) - Trio III (1994), Sonata B for percussion and piano (2005) and the two Concerts for piano and orchestra (1995-97; 2002). -

MADEMOISELLE - Première Audience

MADEMOISELLE - Première Audience Unknown Music of NADIA BOULANGER DE 3496 1 DELOS DE 3496 NADIA BOULANDER DELOS DE 3496 NADIA BOULANDER MADEMOISELLE – Première Audience Unknown Music of NADIA BOULANGER SONGS: Versailles* ♦ J’ai frappé ♦ Chanson* ♦ Chanson ♦ Heures ternes* ♦ Le beau navire* ♦ Mon coeur* ♦ Doute ♦ Un grand sommeil noir* ♦ L’échange ♦ Soir d’hiver ♦ Ilda* ♦ Prière ♦ Cantique ♦ Poème d’amour* ♦ Extase* ♦ La mer* ♦ Aubade* ♦ Au bord de la route ♦ Le couteau ♦ Soleils couchants ♦ Élégie ♦ O schwöre nicht* ♦ Was will die einsame Thräne? ♦ Ach, die Augen sind es wieder* ♦ Écoutez la chanson bien douce WORKS FOR PIANO: Vers la vie nouvelle ♦ Trois pièces pour piano* • • MADEMOISELLE - PREMIÈRE AUDIENCE MADEMOISELLE - PREMIÈRE AUDIENCE WORKS FOR CELLO AND PIANO: Trois pièces WORKS FOR ORGAN: Trois improvisations ♦ Pièce sur des airs populaires flamands Nicole Cabell, soprano • Alek Shrader, tenor Edwin Crossley-Mercer, baritone • Amit Peled, cello François-Henri Houbart, organ • Lucy Mauro, piano A 2-CD Set • Total Playing Time: 1:48:27 * World Premiere Recordings DE 3496 ORIGINAL ORIGINAL DIGITAL © 2017 Delos Productions, Inc., DIGITAL P.O. Box 343, Sonoma, CA 95476-9998 (800) 364-0645 • (707) 996-3844 [email protected] • www.delosmusic.com MADEMOISELLE – Première Audience Unknown Music of NADIA BOULANGER CD 1 (54:12) ‡ 4. Was will die einsame Thräne? (2:32) ‡ 5. Ach, die Augen sind es wieder* (2:09) SONGS † 6. Écoutez la chanson bien douce (6:03) † 1. Versailles* (3:05) † 2. J’ai frappé (1:59) WORKS FOR PIANO ‡ 3. Chanson* (1:26) 7. Vers la vie nouvelle (4:30) ‡ 4. Chanson (2:02) Trois pièces pour piano* (3:22) † 5. -

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS a Discography Of

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers H-P GAGIK HOVUNTS (see OVUNTS) AIRAT ICHMOURATOV (b. 1973) Born in Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia. He studied clarinet at the Kazan Music School, Kazan Music College and the Kazan Conservatory. He was appointed as associate clarinetist of the Tatarstan's Opera and Ballet Theatre, and of the Kazan State Symphony Orchestra. He toured extensively in Europe, then went to Canada where he settled permanently in 1998. He completed his musical education at the University of Montreal where he studied with Andre Moisan. He works as a conductor and Klezmer clarinetist and has composed a sizeable body of music. He has written a number of concertante works including Concerto for Viola and Orchestra No1, Op.7 (2004), Concerto for Viola and String Orchestra with Harpsicord No. 2, Op.41 “in Baroque style” (2015), Concerto for Oboe and Strings with Percussions, Op.6 (2004), Concerto for Cello and String Orchestra with Percussion, Op.18 (2009) and Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op 40 (2014). Concerto Grosso No. 1, Op.28 for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, Piano and String Orchestra with Percussion (2011) Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp (2009) Elvira Misbakhova (viola)/Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + Concerto Grosso No. 1 and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) ARSHAK IKILIKIAN (b. 1948, ARMENIA) Born in Gyumri Armenia. -

Maxwell Davies

Peter MAXWELL DAVIES Sonata for Violin Alone Dances from The Two Fiddlers Sonata for Violin and Piano Piano Trio: A Voyage to Fair Isle Duccio Ceccanti, Violin Vittorio Ceccanti, Cello Matteo Fossi, Piano • Bruno Canino, Piano Peter Maxwell Davies (b. 1934): Sonata for Violin Alone Dances from ‘The Two Fiddlers’ • Sonata for Violin and Piano • Piano Trio: A Voyage to Fair Isle This recording focusses for the most part on more recent Stromness. Although central to the denouement of the the Gianicolo. I imagine arriving on the heights of the demands on the island chorus and the folk musicians that chamber works by the late Peter Maxwell Davies. Such opera, with its use of supernatural elements, these make Gianicolo, when all the bells of Rome’s churches ring out would daunt professionals, but which, in performance, music forms the central part of his composing in this for an effective recital piece in their own right. After a call in joyous clangour.” gave everyone huge satisfaction. I was most of all moved period, notably a cycle of ten ‘Naxos’ String Quartets as to attention, the first dance unfolds as a lively and The work begins with a musing interplay that soon by this extraordinary expression of a community’s emerged between 2002 and 2007 [the whole series is humorous jig. There follows a pensive dialogue with brief takes on a more forceful and increasingly combative essence: one felt a challenging piece of new music had recorded on Naxos 8.505225, 5 CDs), but there are syncopated interludes which build to a brusque climax, quality, though this itself diversifies as these instruments really permeated, through months of rehearsal, into the various sundry pieces in which Davies investigates the followed by a heavily accented dance with pungent evolve highly contrasted personas in which elements of spirit of Fair Isle, so as to become a part of its fabric in a possibilities of other ‘classical’ chamber combinations – harmonies.