Humanizing the Seas a Case for Integrating the Arts and Humanities Into Ocean Literacy and Stewardship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Economy of Technical Fixes: the (Mis)Alignment of Clean Fossil and Political Regimes

The political economy of technical fixes: the (mis)alignment of clean fossil and political regimes Accepted for publication in Energy Research & Social Science Nils Markussona*, Mads Dahl Gjefsenb, Jennie C. Stephensc and David Tyfieldd a Lancaster University, Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK. [email protected] b University of Wisconsin-Madison, Robert F. & Jean E. Holtz Center for Science & Technology Studies, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA. [email protected] c University of Vermont, 81 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405 USA. [email protected] d Lancaster University, Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK. [email protected] *Corresponding Author Abstract This paper argues that existing critiques of technical fixes are unable to explain our simultaneous enamourment and distrust with technical fixes, and that to do so, we need a political economy analysis. We develop a critical, theoretically grounded conceptualisation of technical fixes as imagined defensive spatio-temporal fixes of specific political economic regimes, and apply it to the case of geoengineering, or ‘clean fossil’, as an attempted technical fix of the climate change problem. We map the promises of clean fossil as proposed solutions to the problem of climate change in discrete episodes since the 1960s. The paper shows that clean fossil promises have been surprisingly poorly aligned with the neoliberal regime, and explains how they have been moderately stable due to those misalignments. We also show that different liberal capitalisms could be supported by different clean fossil technologies, but also that illiberal or more egalitarian regimes remain possible alongside particular, perhaps radically re-envisioned, versions of clean fossil. -

The Political Economy of Geoengineering As Plan B: Technological Rationality, Moral Hazard, and New Technology

New Political Economy ISSN: 1356-3467 (Print) 1469-9923 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cnpe20 The Political Economy of Geoengineering as Plan B: Technological Rationality, Moral Hazard, and New Technology Ryan Gunderson, Diana Stuart & Brian Petersen To cite this article: Ryan Gunderson, Diana Stuart & Brian Petersen (2019) The Political Economy of Geoengineering as Plan B: Technological Rationality, Moral Hazard, and New Technology, New Political Economy, 24:5, 696-715, DOI: 10.1080/13563467.2018.1501356 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1501356 Published online: 24 Jul 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1028 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 10 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cnpe20 NEW POLITICAL ECONOMY 2019, VOL. 24, NO. 5, 696–715 https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1501356 The Political Economy of Geoengineering as Plan B: Technological Rationality, Moral Hazard, and New Technology Ryan Gundersona, Diana Stuartb and Brian Petersenc aDepartment of Sociology and Gerontology, Miami University, Oxford, OH, USA; bSchool of Earth Sciences and Sustainability, Program in Sustainable Communities, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, USA; cDepartment of Geography, Planning and Recreation, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Geoengineering would mask and reproduce capital’s contradictory needs Solar radiation management; to self-expand, on the one hand, and maintain a stable climate system, on stratospheric sulfate the other. The Plan B frame, which presents geoengineering as a back-up injection; framing; Frankfurt plan to address climate change in case there is a failure to sufficiently School; Marcuse; technology studies reduce emissions (Plan A), is one means to depict this condition to the public and is a product of, and appeals to, a prevalent ‘technological rationality’. -

The Role of Environmental Attitudes in Explaining Public Perceptions of Climate Change and Renewable Energy Technologies in Lithuania

sustainability Article The Role of Environmental Attitudes in Explaining Public Perceptions of Climate Change and Renewable Energy Technologies in Lithuania Aiste˙ Balžekiene˙ * and Agne˙ Budžyte˙ Civil Society and Sustainability Research Group, Faculty of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities, Kaunas University of Technology, 44249 Kaunas, Lithuania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Baltic states in general and Lithuania in particular represent a controversial combi- nation of rapidly increasing climate change impacts and moderate or low concern with the climate crisis. A value shift is essential for the societal support and acceptance of renewable energy solutions. This study investigates the role of environmental attitudes in shaping the acceptance and risk per- ceptions of renewable energy technologies. The article analyses how environmental attitudes are shaping public attitudes towards climate change and perceptions of renewable energy technologies in Lithuania using New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) and environmental identity questions. The study analyses data from a representative public opinion survey with 1029 respondents conducted in Lithuania. The results reveal that environmental identity is a more significant factor in shaping risk perceptions of renewable technologies than is the NEP scale. The balance of nature dimension from the NEP is more closely related to perceptions of renewables than are humans’ right to rule Citation: Balžekiene,˙ A.; Budžyte,˙ A. The Role of Environmental Attitudes claims. The results show that environmental attitudes have low explanatory power in explaining in Explaining Public Perceptions of perceptions of energy technologies in Lithuania. Climate Change and Renewable Energy Technologies in Lithuania. Keywords: environmental attitudes; climate change perceptions; renewable energy; risk perception; Sustainability 2021, 13, 4376. -

Supporting Report 2 China's Growth Through Technological

Supporting Report 2 China’s Growth through Technological Convergence and Innovation 161 162 CHINA 2030 Summary . 163 Introduction . 166 I . Growth Drivers: Betting on TFP . 167 II . Building Technological Capacity . 175 III . The Road to Innovation: Assets and Speed Bumps . 183 IV . Defining Policy Priorities . 189 V . Some Key Areas for Innovation . 201 Annex A: Annex Tables . 208 References . 219 CHINA‘S GROWTH THROUGH TECHNOLOGICAL CONVERGENCE AND INNOVATION 163 Executive Summary Income gaps among countries are largely explained by differences in productivity . By raising the capital/labor ratio and rapidly assimilating technologies across a wide range of activities, China has increased factor productivity manifold since 1980 and entered the ranks of middle income countries . With the launch of the 12th FYP, China has re-affirmed its goal of becoming a mod- erately prosperous society by 2020 . This report maintains that China can become a high income country by 2030 through a strategy combining high levels of investment with rapid advances in technology comparable to that of Japan from the 1960s through the 1970s and Korea’s from the 1980s through the end of the century . During the next decade, more of the gains in productiv- ity are likely to derive from technology absorption and adaptation supplemented by incremental innovation, while high levels of investment will remain an important source of growth in China through deepening and embodied technological change . By 2030, China expects to have pulled abreast technologically of the most advanced countries and increasingly, its growth will be paced by innovation which pushes outwards the technology frontier in areas of acquired comparative advantage . -

Climate Deniers, Skeptics and Warmistas: “Sticks and Stones Will Hurt …”

Climate Deniers, Skeptics and Warmistas: “Sticks and stones will hurt …” G. Cornelis van Kooten July 10, 2012 The debate on climate change has seen such anti-scientific venom that one wonders about the whole project. The debate essentially involves two sides: One takes the view that climate change is caused by anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases but adds to it a policy conclusion that, unless world governments immediately take action to limit greenhouse gas emission, particularly carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning, a catastrophe will occur. The catastrophe is not clearly specified, although, depending on the commentator, it involves everything from the loss of biodiversity, reduced crop yields and adverse health impacts to the very destruction of the human race as we are either ‘burned’ to death or, more likely, engage in a cataclysmic war caused by mass migration of climate refugees, resource grabs or some other factor. Apparently, once some threshold concentration of atmospheric CO2 is reached, the climate feedbacks are all lined up to overheat the globe. Technological solutions such as those that dramatically reduce solar radiation by increasing the Earth’s albedo, which are implemented once we discover than warming appears to be ‘running away on us’ (i.e., catastrophic), are ruled out. Mitigation by reducing fossil fuel use, and not adaptation or some sort of technological fix, is considered to be the only solution to the threat of climate change. The alternative view actually consists of several positions, all of which are treated by the first group as implausible. Several take the view that, while CO2 and other greenhouse gases do lead to some warming, the amount of CO2 currently in the atmosphere, and expected to enter the atmosphere in the near future, is extremely small so the warming will be tiny as well. -

GC43G-1606 Ethical Considerations for Deploying Geoengineering (GE) Solutions to Mitigate Global Climate Change *James Wang and Iris T

GC43G-1606 Ethical Considerations for Deploying Geoengineering (GE) Solutions to Mitigate Global Climate Change *James Wang and Iris T. Stewart-Frey Department of Environmental Studies and Sciences Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA, 95053 *undergraduate student Research Question Geoengineering Approaches Ethical Considerations As global CO2 levels have increased past 400 ppm, GE methods to Solar Radiation Carbon Dioxide Removal Enhanced Weather • Moral Hazard – encourage inaction, denial of climate mitigate, or at least dampen, the impact of human-induced climate Management (SRM) (CDR) Modification (EWM) change, or “business-as-usual” mindset change are considered worldwide. While many technical and • Technological Fix – seductive/attractive idea of technology political issues regarding GE remain to be resolved, the ethical Pros • Cools planet fastest • Least risky and uncertain • Increases albedo as the solution and reduces complexity of the issue questions regarding who bears the risks, responsibilities, and • Proven effectiveness • Natural approach • Aids drought adaptation • Lesser of Two Evils – should not be the final option and impacts of GE have yet to be widely discussed. • Addresses source of UV • Easily scalable • Prevents temperature rise urgency has diluted our opinions 1. How do young adults (most likely to be impacted by climate Cons • Technologically-advanced • Long-term approach • Varied levels of success change) view the use of GE technology? Environmental Justice • Expensive to deploy • Potentially less effective • Unsure of scalability 2. What are the ethical aspects of deploying GE technologies • Loss of aesthetic • Ecological impact • Expensive to implement • Climate Colonialism – wealthier countries deploy and how can they guide implementation criteria? • Risk of damage • Unsustainable technologies which can create more harms for poorer 3. -

Framing Hydropower As Green Energy: Assessing Drivers, Risks and Tensions in the Eastern Himalayas

Earth Syst. Dynam., 6, 195–204, 2015 www.earth-syst-dynam.net/6/195/2015/ doi:10.5194/esd-6-195-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Framing hydropower as green energy: assessing drivers, risks and tensions in the Eastern Himalayas R. Ahlers1, J. Budds2, D. Joshi3, V. Merme4, and M. Zwarteveen3,5 1Independent researcher, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 2School of International Development, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK 3Water Resources Management, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the Netherlands 4Independent researcher, The Hague, the Netherlands 5Integrated Water Systems and Governance, UNESCO-IHE, Governance and Inclusive Development, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Correspondence to: D. Joshi ([email protected]) Received: 8 September 2014 – Published in Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss.: 13 November 2014 Revised: 9 February 2015 – Accepted: 28 February 2015 – Published: 15 April 2015 Abstract. The culturally and ecologically diverse region of the Eastern Himalayas is the target of ambitious hydropower development plans. Policy discourses at national and international levels position this development as synergistically positive: it combines the production of clean energy to fuel economic growth at regional and national levels with initiatives to lift poor mountain communities out of poverty. Different from hydropower development in the 20th century in which development agencies and banks were important players, contemporary initiatives importantly rely on the involvement of private actors, with a prominent role of the private finance sector. This implies that hydropower development is not only financially viable but also understood as highly profitable. This paper examines the new development of hydropower in the Eastern Himalayas of Nepal and India. -

Science, Technology, and Sustainability: Building a Research Agenda

Science, Technology, and Sustainability: Building a Research Agenda National Science Foundation Supported Workshop Sept. 8-9, 2008 Report Prepared by: Clark Miller Arizona State University Daniel Sarewitz Arizona State University Andrew Light George Mason University Society Nature Knowledge, ideas, and val- ues Science, tech- nology, and governance Socio-technological systems Economy 1 Introduction Over the last decade, the thesis that scientific and technological research can contribute to over- coming sustainability challenges has become conventional wisdom among policy, business, and research leaders.1 By contrast, relatively little attention has been given to the question of how a better understanding of the human and social dimensions of science and technology could also contribute to improving both the understanding of sustainability challenges and efforts to solve them. Yet, such analyses would seem central to sustainability research. After all, human applica- tions of science and technology pose arguably the single greatest source of threats to global sus- tainability, whether we are talking about the energy and transportation systems that underpin global industrial activities or the worldwide expansion of agriculture into forest and savannah ecosystems. These applications arise out of complex social, political, and economic contexts – and they intertwine science, technology, and society in their implementation – making know- ledge of both the human and social contexts and elements of science and technology essential to understanding and responding to sustainability challenges. Thus, while science and technology are central to efforts to improve human health and wellbeing,2 the application of science and technology has not always contributed as anticipated in past efforts to improve the human condi- tion.3 It is essential, therefore, that research on the relationships between science, technology, and society be integrated into the broader sustainability research agenda. -

Framing Hydropower As Green Energy: Risks and Tensions in the E

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss., 5, 1521–1541, 2014 www.earth-syst-dynam-discuss.net/5/1521/2014/ doi:10.5194/esdd-5-1521-2014 ESDD © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 5, 1521–1541, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Earth System Framing hydropower Dynamics (ESD). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in ESD if available. as green energy: assessing drivers, Framing hydropower as green energy: risks and tensions in the E. Himalayas assessing drivers, risks and tensions in R. Ahlers et al. the Eastern Himalayas Title Page R. Ahlers1, J. Budds2, D. Joshi3, V. Merme1, and M. Zwarteveen4 Abstract Introduction 1Independent researcher, the Netherlands 2School of International Development, University of East Anglia, Norwich, Conclusions References Norfolk, NR4 7TJ, UK 3Water Resources Management, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the Netherlands Tables Figures 4Integrated Water Systems and Governance, UNESCO-IHE; Governance and Inclusive Development, University of Amsterdam; Water Resources Management, Wageningen J I University, Wageningen, the Netherlands J I Received: 8 September 2014 – Accepted: 14 October 2014 – Published: 13 November 2014 Back Close Correspondence to: D. Joshi ([email protected]) Full Screen / Esc Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 1521 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract ESDD The culturally and ecologically diverse region of the Eastern Himalayas is the target of ambitious hydropower development plans. Policy discourses at national and inter- 5, 1521–1541, 2014 national levels position this development as synergistically positive: it combines the 5 production of clean energy to fuel economic growth at regional and national levels with Framing hydropower initiatives to lift poor mountain communities out of poverty. -

Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture 1966

Alfred Korzybski Memorial lecture 1966 WILL TECHNOLOGY REPLACE SOCIAL ENGINEERING?* Alvin M. Weinberg Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee One of the most important lessons we have learned from our experience during and after the war has been that large-scale, organized research can solve the most difficult technological problems . Nuclear re- actors, nuclear bombs, space radar, possibly desalination, are miraculous new technologies that have been created by concerted efforts sponsored by our Federal Government . Before launching a systematic attack on these problems we had to identify them as being worth solving and as being solvable . Each of these de- velopments aimed at answering a technological question, i . e . , a question that could be posed in strictly technological, as opposed to social, terms . The answer to each question was found entirely within the nat- ural sciences and technology . For example, after nuclear fission had been discovered, rather by accident in 1938, it occurred to many physicists that nuclear energy could be relased on a large scale . The Man- hattan Project was mobilized to exploit the discovery of fission ; the project and its daughters, spawned by the Atomic Energy Commission, were prototypes of the technologically oriented, large - scale government project . Though these federally-sponsored developments stretched our science to the utmost, in two important senses they have been relatively simple . First, to mobilize around a well-defined technological goal only a 9 few people had to be convinced . President Kennedy decided almost single-handedly that we should send a man to the moon, and this was enough to start the space program in a straight -forward and efficient way . -

The Role of Technology in Sustainable Development

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities January 2000 The Role of Technology in Sustainable Development Sharon Beder University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Beder, Sharon, The Role of Technology in Sustainable Development 2000. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/48 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] 1 The Role of Technology in Sustainable Development Sharon Beder, There is a great reliance on technology to solve environmental problems around the world today, because of an almost universal reluctance by governments and those who advise them to make the social and political changes that would be necessary to reduce growth in production and consumption. Yet the sorts of technological changes that would be necessary to keep up with and counteract the growing environmental damage caused by increases in prod uction and consumption would have to be fairly dramatic. The technological fixes of the past will not do. And the question remains, can such a dramatic and radical redesign of our technological systems occur without causing major social changes and will it occur without a rethinking of political priorities? Technology is not independent of society either in its shaping or its effects. At the heart of the debate over the potential effectiveness of sustainable development is the question of whether technolo gical change, even if it can be achieved, can reduce the impact of economic development sufficiently to ensure other types of change will not be necessary. -

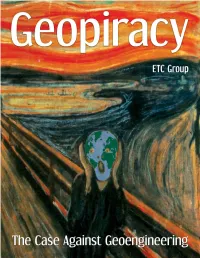

Geopiracy: the Case Against Geoengineering I Geopiracy: the Case Against Geoengineering

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Albert Einstein “We already are inadvertently changing the climate. So why not advertently try to counterbalance it?” Michael MacCracken, Climate Institute, USA About the cover ETC Group gratefully acknowledges the financial support of SwedBio The cover is an adaptation of The (Sweden), HKH Foundation (USA), Scream by Edvard Munch, painted in CS Fund (USA), Christensen Fund 1893, shown on the right. Munch (USA), Heinrich Böll Foundation painted several versions of this image (Germany), the Lillian Goldman over the years, which reflected his Charitable Trust (USA), Oxfam Novib feeling of "a great unending scream (Netherlands), and the Norwegian piercing through nature." One theory is Forum for Environment and that the red sky was inspired by the Development. ETC Group is solely eruption of Krakatoa, a volcano that responsible for the views expressed in cooled the Earth by spewing sulphur this document. into the sky, which blocked the sun. Geoengineers seek to artificially Copy-edited by Leila Marshy reproduce this process. Design by Shtig (.net) Geopiracy: The Case Against Acknowledgements Geoengineering is ETC Group We also thank the Beehive Collective Communiqué # 103 ETC Group is grateful to Almuth for artwork and all the participants of First published October 2010 Ernsting of Biofuelwatch, Niclas the HOME campaign for their ongoing Second edition November 2010 Hällström of the Swedish Society for participation and support as well as the Conservation of Nature (that Leila Marshy and Shtig for good- All ETC Group publications are published Retooling the Planet from humoured patience and professionalism available free of charge on our website: which some of this material is drawn).