Gagosian Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sampson Theater Market and Feasibility Analysis

Pennsylvania Yankee Theater Company Sampson Theatre Project Market and Feasibility Analysis Shepstone Management Company, Inc. Planning & Research Consultants 100 Fourth Street, Honesdale, PA 18431 570-251-9550 FAX 251-9551 [email protected] www.shepstone.net December, 2010 Pennsylvania Yankee Theater Company - Sampson Theatre Project Market and Feasibility Analysis Table of Contents Page 1.0 Project Background and Description 1-1 2.0 Market Definition and Overview 2-1 3.0 Comparable Projects in Market Area 3-1 4.0 Market Analysis 4-1 4.1 Market Demand Trends 4-1 4.2 Projected Market Activity 4-3 4.3 Projected Capture Rate 4-4 5.0 Financial Feasibility Analysis 5-1 5.1 Prospective Capital Costs 5-1 5.2 Prospective Operating Costs 5-1 5.3 Cash Flow Analysis 5-3 5.4 Required Financing 5-4 6.0 Summary Conclusions and Recommendations 6-1 Appendices: A - ESRI Market Data B - Comparable Project Information C - Other Background Data and Information Shepstone Management Company Table of Contents Planning & Research Consultants Pennsylvania Yankee Theater Company - Sampson Theatre Project Market and Feasibility Analysis 1.0 Project Background and Description The Pennsylvania Yankee Theater Company (PYTCO) is a non-profit theater group located in Penn Yan, NY. It owns the Sampson Theater building located at the corner of East Elm Street and Champlin Avenue, which was donated to it in 2004. The Sampson Theatre, constructed in 1910 and operated as a theater until 1930, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. PYTCO began a renovation of the building with a grant-funded roof replacement that has now been completed and seeks to fully restore the building for use, once again, as a theater and as a community cultural and conference center. -

Mister Lonely

MISTER LONELY von Harmony Korine USA/Großbritannien/Frankreich/Irland 2006 35 mm 112 Min. engl. OF Drehbuch: Harmony Korine Avi Korine Kamera: Marcel Zyskind Schnitt: Paul Zucker Valdís Oskarsdóttir Musik: Ason Spaceman The Sun City Girls Produzent: Nadja Romain Produktion: O’Salvation Cine Recorded Picture Company Film4 Love Streams Productions Arte France Cinéma Vertrieb/Verleih: Celluloid Dreams Darsteller: Diego Luna Samantha Morton Werner Herzog Denis Lavant James Fox Leos Carax Anita Pallenberg Rachel Simon Nur jemand wie der Ausnahmekünstler Harmony Korine (Regisseur von GUMMO, Drehbuch- Harmony Korine wurde 1973 in Bolinas, Kalifornien, geboren und autor von KIDS) kann Michael Jackson, Marilyn Monroe, den Papst und fliegende Nonnen in wuchs zunächst in Nashville auf. Später zog er zu seiner Großmut- einem wunderbar poetischen Film über Selbstfindung und Selbstinszenierung zusammen- ter nach New York. Er studierte kurze Zeit englische Literatur an bringen. MISTER LONELY ist ein Michael-Jackson-Double (Diego Luna), der vereinsamt in der New York University und verdiente sein Geld als professioneller Paris lebt und seine Show auf der Straße und in Altersheimen zeigt. Dabei trifft er auf eine Stepptänzer. Mit 22 Jahren schrieb Korine das Drehbuch zu Larry bildhübsche Frau, die sich als Marilyn Monroe (Samantha Morton) ausgibt. Sie überredet ihn, Clarks Film KIDS, wodurch er schlagartig berühmt wurde. Für Clark in eine Kommune in die schottischen Highlands zu ziehen, wo lauter Imitatoren leben. Dort schrieb er auch das Drehbuch zu KEN PARK. Im Jahr 1997 entstand trifft Michael auf Marilyns besitzergreifenden Ehemann Charlie Chaplin und ihre Tochter Shir- sein eigenes Regiedebüt GUMMO. Korine arbeitet auch als Regis- ley Temple. -

Ideology of the Absurd Jeremy D

Cinesthesia Volume 4 | Issue 2 Article 2 4-23-2015 That’s Why I’m Lonely: Ideology of the Absurd Jeremy D. Knickerbocker Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Knickerbocker, Jeremy D. (2015) "That’s Why I’m Lonely: Ideology of the Absurd," Cinesthesia: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol4/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Knickerbocker: That’s Why I’m Lonely: Ideology of the Absurd “It is not only our reality which enslaves us,” according to Slovenian psychoanalytic philosopher Slovoj Zizek, “when we think that we escape it into our dreams, at that point we are within ideology” (Pervert, 2012). It has long been the task of cultural criticism to uncover the functioning value systems which guide our actions and structure the ways in which we make sense of our experiences. All stories, as cultural productions, take for granted certain assumptions as to the way things are, the way things came to be, and the way things ought to be. The ideologies that these assumptions comprise tend to be culturally specific, often functioning as myths which naturalize political and economic systems—or to be less specific—simply the way things are. These social doctrines are always philosophically grounded, and therefore can be said to transcend politics. -

Film Calendar February 8 - April 4, 2019

FILM CALENDAR FEBRUARY 8 - APRIL 4, 2019 TRANSIT A Christian Petzold Film Opens March 15 Chicago’s Year-Round Film Festival 3733 N. Southport Avenue, Chicago www.musicboxtheatre.com 773.871.6607 CATVIDEOFEST RUBEN BRANDT, THE FILMS OF CHRISTIAN PETZOLD IDA LUPINO’S FEBRUARY COLLECTOR HARMONY KORINE MATINEE SERIES THE HITCH-HIKER 16, 17 & 19 OPENS MARCH 1 MARCH 15-21 WEEKENDS AT 11:30AM MARCH 4 AT 7PM Welcome TO THE MUSIC BOX THEATRE! FEATURE FILMS 4 COLD WAR NOW PLAYING 4 OSCAR-NOMINATED DOC SHORTS OPENS FEBRUARY 8 6 AMONG WOLVES FEBRUARY 8-14 6 NEVER LOOK AWAY OPENS FEBRUARY 15 8 AUDITION FEBRUARY 15 & 16 9 LORDS OF CHAOS OPENS FEBRUARY 22 9 RUBEN BRANDT, COLLECTOR OPENS MARCH 1 11 BIRDS OF PASSAGE OPENS MARCH 8 FILM SCHOOL DEDICATED 12 TRANSIT OPENS MARCH 15 The World’s Only 17 WOMAN AT WAR OPENS MARCH 22 TO COMEDY 18 COMMENTARY SERIES Comedy Theory. Storytelling. Filmmaking. Industry Leader Masterclasses. 24 CLASSIC MATINEES Come make history with us. RamisFilmSchool.com 26 CHICAGO FILM SOCIETY 28 SILENT CINEMA 30 MIDNIGHTS SPECIAL EVENTS 7 VALENTINE’S DAY: CASABLANCA FEBRUARY 10 VALENTINE’S DAY: THE PRINCESS BRIDE FEBRUARY 13 & 14 8 CAT VIDEO FEST FEBRUARY 16, 17 & 19 10 JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL MARCH 1-17 10 THE HITCH-HIKER MARCH 4 11 PARTS OF SPEECH: HARI KUNZRU MARCH 12 14 HARMONY KORINE FILM SERIES MARCH 15-21 17 DECONSTRUCTING THE BEATLES MARCH 30 & APRIL 3 Brian Andreotti, Director of Programming VOLUME 37 ISSUE 154 Ryan Oestreich, General Manager Copyright 2019 Southport Music Box Corp. -

Loki Production Brief

PRODUCTION BRIEF “I am Loki, and I am burdened with glorious purpose.” —Loki arvel Studios’ “Loki,” an original live-action series created exclusively for Disney+, features the mercurial God of Mischief as he steps out of his brother’s shadow. The series, described as a crime-thriller meets epic-adventure, takes place after the events Mof “Avengers: Endgame.” “‘Loki’ is intriguingly different with a bold creative swing,” says Kevin Feige, President, Marvel Studios and Chief Creative Officer, Marvel. “This series breaks new ground for the Marvel Cinematic Universe before it, and lays the groundwork for things to come.” The starting point of the series is the moment in “Avengers: Endgame” when the 2012 Loki takes the Tesseract—from there Loki lands in the hands of the Time Variance Authority (TVA), which is outside of the timeline, concurrent to the current day Marvel Cinematic Universe. In his cross-timeline journey, Loki finds himself a fish out of water as he tries to navigate—and manipulate—his way through the bureaucratic nightmare that is the Time Variance Authority and its by-the-numbers mentality. This is Loki as you have never seen him. Stripped of his self- proclaimed majesty but with his ego still intact, Loki faces consequences he never thought could happen to such a supreme being as himself. In that, there is a lot of humor as he is taken down a few pegs and struggles to find his footing in the unforgiving bureaucracy of the Time Variance Authority. As the series progresses, we see different sides of Loki as he is drawn into helping to solve a serious crime with an agent 1 of the TVA, Mobius, who needs his “unique Loki perspective” to locate the culprits and mend the timeline. -

Only the Lonely

34 MISTER LONELY Screen International February 2, 2007 SET REPORT Samantha Morton and Denis Levant ONLY THE in Mr Lonely LONELY It’s been a long road back for indie wunderkind Harmony Korine, but his new project finds him brimming with enthusiasm and working with a starry cast. He tells FIONNUALA HALLIGAN how the dark years helped create his “best work” t has been a decade since Gummo and a good sional Madonna impersonator) and Abraham Early highs eight years since Julien Donkey-Boy, and Lincoln (Richard Strange). Mister Lonely is being readied for Cannes Harmony Korine is finally back behind the Running through this story, somehow and after a lengthy spell in the film wilderness, Icamera with Mister Lonely. He co-scripted — Korine will not be drawn — is the Panama Korine is definitely back — he has two more the story about celebrity impersonators — the thread which features magician David Blaine projects ready to roll, with which Agnes B wants key characters being “Michael Jackson” and and Werner Herzog. to be involved. Agnes, a grandmother, helped “Marilyn Monroe” — with his younger brother At $8.2m, Mister Lonely is a considerable the troubled 34-year-old get his life back on Avi, the first time the writer of Kids has collabo- step up for a Harmony Korine project, although track after they first met at Venice at the premiere rated on a screenplay. That, however, is possi- admittedly it is only his third as director. It is of Julien Donkey-Boy. bly the least unusual part of Mister Lonely. being produced by the French fashion designer “She let me lean on her. -

Realism and Ambiguity 13 2

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town A Strange Mirror: Realism, Ambiguity and Absence in the work of Harrnony Korine Alexia Jayne Smit SMTALEOlO A dissertation submitted infuljillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2007 The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinionsy ofexpressed Cape and conclusions Town arrived at, are those of the author and not necessarilysit to be attributed to the NRF. COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. EachUniver significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced . Signature: __---'~~ _____________Date: 67101107 UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN GRADUATE SCHOOL IN HUMANITIES DECLARATION BY CANDIDATE FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN THE F ACUL TY OF HUMANITIES I, (name of candidate) Alexia Jayne Smit of (address of candidate) 37 Anerley Road, Morningside, Durban 4001 do hereby declare that I empower the University of Cape Town to produce for the purpose of research either the whole or any portion of the contents of my dissertation entitled A Strange Mirror: Realism, Ambiguity and Absence in the work of Harmony Korine. -

Chloë Sevigny Says of Korine

4. MAN OF THE MOMENT 2. 3. 5. 6. 1. 7. 8. 10. 1. Korine and Al Pacino, at the Toronto International Film Festival, 2014. 2. Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Benson, Rachel Korine, and Selena Gomez (from left), in Spring Breakers, 2012. 3. Werner Herzog, in Mister Lonely, 2007. 4. Korine and Lil Wayne, Tampa, Florida, 2012. 5. David Blaine and Korine, at a Jeremy Scott event, 2004. 6. Chloë Sevigny, in Kids, 1995. 7. Jeffrey Deitch and Korine, at a private reception for “Rebel,” 2012. 8. Korine and James Franco, Los Angeles, 2012. 9. Jacob Sewell, in Gummo, 1997. 10. Dakota Johnson, Emily Ward, and Korine (from left), at the exhibition “First Show/Last Show,” in New York, organized by Vito Schnabel, 2015. fluorescent fan blades spinning on high. Amid the paintings are bikes and toys belonging to Korine’s 7-year-old daughter, Lefty (named after the country music icon Lefty Frizzell), and a video 9. console set up for a game Korine is considering developing. The building, dubbed Voorhees, after the company it used to house, is pretty spartan. Korine tells me he likes it when it’s really empty— “Every single Korine himself is notoriously tricky to pin down. In some circles, working without distraction, he says, allows him to recharge. he’s best known for his association with Larry Clark, but lately he’s “Harmony will do a great movie like Spring Breakers and then thing he did become known for his association with another Larry— Gagosian, disappear,” says the actor James Franco, who starred in that film as his dealer since 2014. -

Intermediality in Contemporary American Independent Film. Doctoral Thesis, Northumbria University

Citation: Mack, Jonathan (2015) (Indie)mediality: Intermediality in Contemporary American Independent Film. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/31604/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html (Indie)mediality: Intermediality in Contemporary American Independent Film J. Mack PhD 2015 1 (Indie)mediality: Intermediality in Contemporary American Independent Film Jonathan Mack A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle The Department of Media and Communication Design October 2015 2 Abstract (Indie)mediality: Intermediality in Contemporary American Independent Film Intermediality has become an umbrella term for a heterogeneous group of concepts as diverse as the creation of an entirely new medium and the mere quotation of a work from one medium in another. -

Harmony Korine Harmony

HARMONY KORINE HARMONY KORINERÉTROSPECTIVE DE FILMS / EXPOSITION / EN PRÉSENCE DE L’ARTISTE 6 OCTOBRE - 5 NOVEMBRE 2017 Dossier Icône : 4 COULEURS UTILISÉES 1 2 3 4 Cyan Magenta Yellow Black 47, avenue Montaigne - 93160 Noisy-le-Grand - Tél +33 (0)1 48 15 16 95 [email protected] • http://iconebox.wetransfer.com • www.icone-brandkeeper.com AVANT-PROPOS SOMMAIRE • Avant-propos de Serge Lasvignes, p. 3 Le cinéaste allemand, Werner Herzog, à qui nous avons rendu hommage en 2008, évoquait au sujet de Harmony Korine et de ses débuts au cinéma qu’il était « l’avenir du cinéma américain ». • Entretien avec Harmony Korine, p. 5 Vingt ans plus tard, après cinq longs métrages et une vingtaine de courts métrages, clips et • Événements, p. 7 publicités, pour la plupart inédits en France, la richesse de l’œuvre de Korine résonne plus que jamais avec cette déclaration. • Films programmés, p. 9 • Exposition, p. 10 Cinéaste et artiste, Harmony Korine a construit tout au long de ces années une œuvre artistique foisonnante : il pratique en parallèle la peinture, le dessin, la photographie et l’écriture. • Les longs métrages, p. 14 Le succès polémique de sa première collaboration en tant que scénariste avec Larry Clark, • Les courts et moyens métrages, p. 19 pour le film Kids (1995), le fait connaître à l’âge de dix-huit ans. Le portrait cru qu’il y dresse d’une jeunesse américaine désaxée devient un de ses thèmes de prédilection. S’ensuit une • Clips, p. 22 carrière cinématographique mouvementée et remarquable inaugurée par deux films qu’il réalise, • Publicités, p. -

The Spatial Politics of Urban Gardening Epic Houseplant Fails the Myth of the Industry Plant Maya Dukmasova 8 Sarah Beckett 19 Leor Galil 27

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | MARCH CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE The spatial politics of urban gardening Epic houseplant fails The myth of the industry plant Maya Dukmasova 8 Sarah Beckett 19 Leor Galil 27 The Plants Issue THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | MARCH | VOLUME NUMBER A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR TR - I KNOW A fair amount about plants, and gar- ethical reasons, because it’s not an easy way to toxins. They are inherently political, and some- @ dening, and the pending environmental disas- eat. But it keeps me alive. And I like it. Making times quite dangerous for cats. John Porcellino ter that we euphemistically refer to as climate cheese out of nuts is a good time! even drew up a “Sunday Strip” (read: full-color) version of Prairie Potholes for the issue, to in- PTB change. In fact, I spent two and a half years Hog butcher for the world, indeed. The lack ECAEM as a small-scale organic farmer in Detroit, of plant-based restaurants in Chicago is an troduce us to a few of his favorite leaf-covered MEPSK and could probably have thrown together a odd blind spot in this otherwise food-focused buddies. Plants are fun, and pretty, and also a MEDKH D EKS good 5,000 words about common household town. Elsewhere such cuisines are easy to complicated pejorative when describing a cer- C LSK substances that not only support your gut find. In Toronto, I dig Planta on Bay Street. tain breed of unusually popular hip-hop artist. D P JR CEAL microflora but will double the size of your In the Detroit area, there’s GreenSpace Cafe They are also extremely tasty. -

Karaoke List

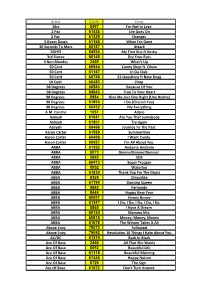

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam