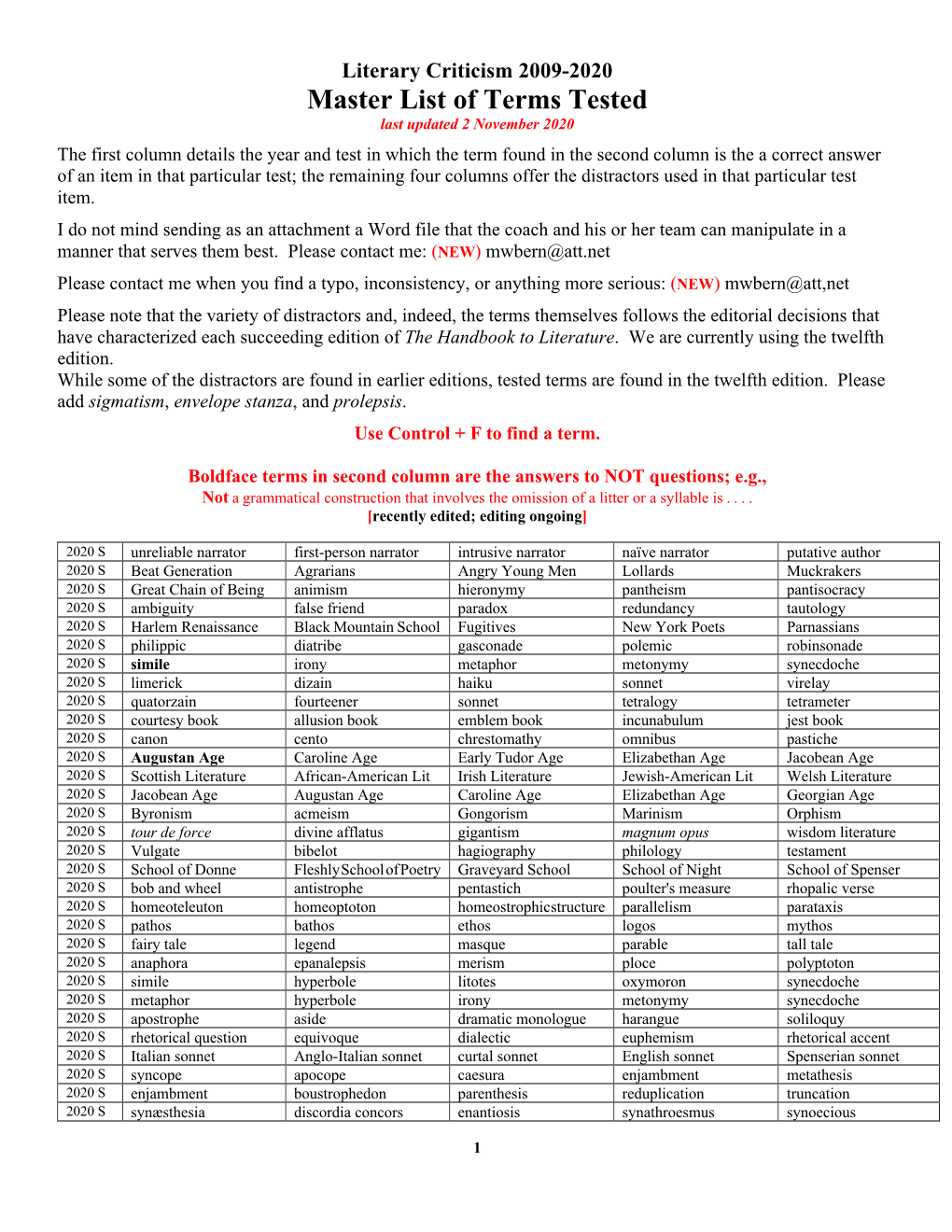

Master List of Terms Tested Last Updated 2 November 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry Paul Kiparsky Stanford University [email protected] Linguistics Department, Stanford University, CA. 94305-2150 July 19, 2009 Review (4872 words) The publication of this joint book by the founder of generative metrics and a distinguished literary linguist is a major event.1 F&H take a fresh look at much familiar material, and introduce an eye-opening collection of metrical systems from world literature into the theoretical discourse. The complex analyses are clearly presented, and illustrated with detailed derivations. A guest chapter by Carlos Piera offers an insightful survey of Southern Romance metrics. Like almost all versions of generative metrics, F&H adopt the three-way distinction between what Jakobson called VERSE DESIGN, VERSE INSTANCE, and DELIVERY INSTANCE.2 F&H’s the- ory maps abstract grid patterns onto the linguistically determined properties of texts. In that sense, it is a kind of template-matching theory. The mapping imposes constraints on the distribution of texts, which define their metrical form. Recitation may or may not reflect meter, according to conventional stylized norms, but the meter of a text itself is invariant, however it is pronounced or sung. Where F&H differ from everyone else is in denying the centrality of rhythm in meter, and char- acterizing the abstract templates and their relationship to the text by a combination of constraints and processes modeled on Halle/Idsardi-style metrical phonology. F&H say that lineation and length restrictions are the primary property of verse, and rhythm is epiphenomenal, “a property of the way a sequence of words is read or performed” (p. -

An Analysis of Vowels Across Word Boundaries in Veracruz, Mexican Spanish

An Analysis of Vowels across Word Boundaries in Veracruz, Mexican Spanish Janet M. Smith, Tanya L. Flores, Michael S. Gradoville Indiana University Bloomington Abstract This project examines vowels in hiatus across word boundaries in Spanish. Our findings are based on a corpus of seven female speakers of the Veracruz variety of Mexican Spanish. Previous research on vowel transitions has proposed several possible outcomes for vowel combinations across word boundaries in Spanish: hiatus, diphthong, reduction or deletion of one vowel, or creation of a new vowel. The purpose of this project was to investigate the conditions under which these outcomes actually occur in running speech using spectrographic analysis. In terms of hiatus, our results support those of a study conducted on the Spanish of northern New Mexico/Southern Colorado by Alba (2006), which concluded that maintaining hiatus was not the preferred outcome. Likewise, in the present study, 94% of our 148 tokens showed non-maintenance of hiatus. Our data did not clearly reveal a single preferred outcome among the non-maintenance tokens, but rather a mixture of tendencies. These varied widely by vowel combination and speaker. Another surprising outcome that deserves attention is centralization. Centralization was present in all four vowel combinations, occurring more frequently than anticipated, given that it is thought not to occur in Spanish. 1. Introduction Our project1 examines vowels in hiatus across word boundaries in the Spanish of seven female speakers of the Veracruz variety of Mexican Spanish. Studies that examine this topic are rare, especially within the realm of laboratory phonology using spectrographic analysis. Prior experiments on the topic have utilized aural perceptions to distinguish vowel sequences in hiatus from those that are diphthongs and it is only recently that 1 We are very grateful to Dr. -

Songs in Fixed Forms

Songs in Fixed Forms by Margaret P. Hasselman 1 Introduction Fourteenth century France saw the development of several well-defined song structures. In contrast to the earlier troubadours and trouveres, the 14th-century songwriters established standardized patterns drawn from dance forms. These patterns then set up definite expectations in the listeners. The three forms which became standard, which are known today by the French term "formes fixes" (fixed forms), were the virelai, ballade and rondeau, although those terms were rarely used in that sense before the middle of the 14th century. (An older fixed form, the lai, was used in the Roman de Fauvel (c. 1316), and during the rest of the century primarily by Guillaume de Machaut.) All three forms make use of certain basic structural principles: repetition and contrast of music; correspondence of music with poetic form (syllable count and rhyme); couplets, in which two similar phrases or sections end differently, with the second ending more final or "closed" than the first; and refrains, where repetition of both words and music create an emphatic reference point. Contents • Definitions • Historical Context • Character and Provenance, with reference to specific examples • Notes and Selected Bibliography Definitions The three structures can be summarized using the conventional letters of the alphabet for repeated sections. Upper-case letters indicate that both text and music are identical. Lower-case letters indicate that a section of music is repeated with different words, which necessarily follow the same poetic form and rhyme-scheme. 1. Virelai The virelai consists of a refrain; a contrasting verse section, beginning with a couplet (two halves with open and closed endings), and continuing with a section which uses the music and the poetic form of the refrain; and finally a reiteration of the refrain. -

Objects in Tom Stoppard's Arcadia

Cercles 22 (2012) ANIMAL, VEGETABLE OR MINERAL? OBJECTS IN TOM STOPPARD’S ARCADIA SUSAN BLATTÈS Université Stendhal—Grenoble 3 The simplicity of the single set in Arcadia1 with its rather austere furniture, bare floor and uncurtained windows has been pointed out by critics, notably in comparison with some of Stoppard’s earlier work. This relatively timeless set provides, on one level, an unchanging backdrop for the play’s multiple complexities in terms of plot, ideas and temporal structure. However we should not conclude that the set plays a secondary role in the play since the mysteries at the centre of the plot can only be solved here and with this particular group of characters. Furthermore, I would like to suggest that the on-stage objects play a similarly vital role by gradually transforming our first impressions and contributing to the multi-layered meaning of the play. In his study on the theatre from a phenomenological perspective, Bert O. States writes: “Theater is the medium, par excellence, that consumes the real in its realest forms […] Its permanent spectacle is the parade of objects and processes in transit from environment to imagery” [STATES 1985 : 40]. This paper will look at some of the parading or paraded objects in Arcadia. The objects are many and various, as can be seen in the list provided in the Samuel French acting edition (along with lists of lighting and sound effects). We will see that there are not only many different objects, but also that each object can be called upon to assume different functions at different moments, hence the rather playful question in the title of this paper (an allusion to the popular game “Twenty Questions” in which the identity of an object has to be guessed), suggesting we consider the objects as a kind of challenge to the spectator, who is set the task of identifying and interpreting them. -

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There are two general forms we will concern ourselves with: verse and prose. Verse is metered, prose is not. Poetry is a genre, or type (from the Latin genus, meaning kind or race; a category). Other genres include drama, fiction, biography, etc. POETRY. Poetry is described formally by its foot, line, and stanza. 1. Foot. Iambic, trochaic, dactylic, etc. 2. Line. Monometer, dimeter, trimeter, tetramerter, Alexandrine, etc. 3. Stanza. Sonnet, ballad, elegy, sestet, couplet, etc. Each of these designations may give rise to a particular tradition; for example, the sonnet, which gives rise to famous sequences, such as those of Shakespeare. The following list is taken from entries in Lewis Turco, The New Book of Forms (Univ. Press of New England, 1986). Acrostic. First letters of first lines read vertically spell something. Alcaic. (Greek) acephalous iamb, followed by two trochees and two dactyls (x2), then acephalous iamb and four trochees (x1), then two dactyls and two trochees. Alexandrine. A line of iambic hexameter. Ballad. Any meter, any rhyme; stanza usually a4b3c4b3. Think Bob Dylan. Ballade. French. Line usually 8-10 syllables; stanza of 28 lines, divided into 3 octaves and 1 quatrain, called the envoy. The last line of each stanza is the refrain. Versions include Ballade supreme, chant royal, and huitaine. Bob and Wheel. English form. Stanza is a quintet; the fifth line is enjambed, and is continued by the first line of the next stanza, usually shorter, which rhymes with lines 3 and 5. Example is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. -

1 Introduction It Is My Goal in This Paper to Offer a Strategy For

Three Archetypes for the Clarification Christopher Yorke Of Utopian Theorizing University of Glasgow Introduction It is my goal in this paper to offer a strategy for translating universal statements about utopia into particular statements. This is accomplished by drawing out their implicit, temporally embedded, points of reference. Universal statements of the kind I find troublesome are those of the form ‘Utopia is x’, where ‘x’ can be anything from ‘the receding horizon’ to ‘the nation of the virtuous’. To such statements, I want to put the questions: ‘Which utopias?’; ‘In what sense?’; and ‘When was that, is that, or will that be, the case for utopias?’ Through an exploration of these lines of questioning, I arrive at three archetypes of utopian theorizing which serve to provide the answers: namely, utopian historicism, utopian presentism, and utopian futurism. The employment of these archetypes temporally grounds statements about utopia in the past, present, or future, and thus forces discussion of discrete particulars instead of abstract universals with no meaningful referents. Given the vague manner in which the term ‘utopia’ is employed in discourse—whether academic or non-academic—confusion frequently, and rightly, ensues. There are various possible sources for this confusion, the first of which is the sheer volume and wide variety of socio-political schemes that have been regarded as utopian, by utopian theorists, historians, or authors of fiction. Bibliographers of utopian literature (such as Lyman Tower Sargent) face the onerous task of sorting out those visions of other worlds that belong in the utopian canon from those that do not. However, utopian bibliographies generally err on the side of inclusiveness, and a sufficient range and number of utopias remain in the realm of discourse to make the practice of distinguishing a utopia from a non-utopia (or even a dystopia) challenging at best and baffling at worst. -

Magis Rythmus Quam Metron: the Structure of Seneca's Anapaests

Magis rythmus quam metron: the structure of Seneca’s anapaests, and the oral/aural nature of Latin poetry Lieven Danckaert To cite this version: Lieven Danckaert. Magis rythmus quam metron: the structure of Seneca’s anapaests, and the oral/aural nature of Latin poetry. Symbolae Osloenses, Taylor & Francis (Routledge): SSH Titles, 2013, 87 (1), pp.148-217. 10.1080/00397679.2013.842310. halshs-01527668 HAL Id: halshs-01527668 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01527668 Submitted on 24 May 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Magis rythmus quam metron : the structure of Seneca's anapaests, and the oral/aural nature of Latin poetry 1 Lieven Danckaert, Ghent University Abstract The aim of this contribution is twofold. The empirical focus is the metrical structure of Seneca's anapaestic odes. On the basis of a detailed formal analysis, in which special attention is paid to the delimitation and internal structure of metrical periods, I argue against the dimeter colometry traditionally assumed. This conclusion in turn is based on a second, more methodological claim, namely that in establishing the colometry of an ancient piece of poetry, the modern metrician is only allowed to set apart a given string of metrical elements as a separate metron, colon or period, if this postulated metrical entity could 'aurally' be distinguished as such by the hearer. -

Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion

APPENDIX B Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion Latin poetry follows a strict rhythm based on the quantity of the vowel in each syllable. Each line of poetry divides into a number of feet (analogous to the measures in music). The syllables in each foot scan as “long” or “short” according to the parameters of the meter that the poet employs. A vowel scans as “long” if (1) it is long by nature (e.g., the ablative singular ending in the first declen- sion: puellā); (2) it is a diphthong: ae (saepe), au (laudat), ei (deinde), eu (neuter), oe (poena), ui (cui); (3) it is long by position—these vowels are followed by double consonants (cantātae) or a consonantal i (Trōia), x (flexibus), or z. All other vowels scan as “short.” A few other matters often confuse beginners: (1) qu and gu count as single consonants (sīc aquilam; linguā); (2) h does NOT affect the quantity of a vowel Bellus( homō: Martial 1.9.1, the -us in bellus scans as short); (3) if a mute consonant (b, c, d, g, k, q, p, t) is followed by l or r, the preced- ing vowel scans according to the demands of the meter, either long (omnium patrōnus: Catullus 49.7, the -a in patrōnus scans as long to accommodate the hendecasyllabic meter) OR short (prō patriā: Horace, Carmina 3.2.13, the first -a in patriā scans as short to accommodate the Alcaic strophe). 583 40-Irby-Appendix B.indd 583 02/07/15 12:32 AM DESIGN SERVICES OF # 157612 Cust: OUP Au: Irby Pg. -

Download (15MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] VERSE FORM IN ENGLISH RENAISSANCE POETRY: A CATALOGUE OF STANZA PATTERNS BY MUNZER ADEL ABSI THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FACULTY OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW 1992 ABSI, M.A. ProQuest Number: 10992066 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10992066 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

AN ANALYSIS of GEORGE SAINTSBURY's a HISTORY of ENGLISH PROSODY Ours Is a Time in Which Those Interested in Language and Literature Are Much Concerned with Theory

AN ANALYSIS OF GEORGE SAINTSBURY'S A HISTORY OF ENGLISH PROSODY Ours is a time in which those interested in language and literature are much concerned with theory. I believe that, to understand our own theories, we can learn from studying the theories of those who have gone before us. In the field of prosody, George Saintsbury's 3- volume A History of English Prosody, which was written almost a century ago, is based on a remarkable theory of the English language, and of versification, which has never been methodically analysed, but which in my view still provides, in its very unsoundness, a provocative challenge to those of us who would like to describe the facts of English prosody more accurately today. Saintsbury's colossal work remains important because it has until fairly recently dominated much prosodic thinking, and because he covered a much larger range of writings (historically and otherwise) than any other prosodist has ever attempted to cope with. He cannot be accused, for example, of limiting his analysis to what literary scholars usually descibe as iambic verse. In what follows I shall try to lay bare just what Saintsbury's theory is, and what is wrong with it. I also intend to show why a fairly representative late twentieth-century `literary' approach such as my own will serve us better as a way of describing the varieties of verse-writing which Saintsbury discusses. Indeed, one central complaint I have about his method (and that of many theorists) is that he treats totally different kinds of writing as though they will, or should, all fit into his theoretical mould. -

CIM/CWRU Joint Music Program Wednesday, Octoberdecember 5, 7,2016 2016

CIM/CWRU Joint Music Program Wednesday, OctoberDecember 5, 7,2016 2016 La Fonteinne amoureuse CarlosCWRU Salzedo Medieval (1885–1961) Ensemble Tango Ross W. Duffin, director Grace Cross & Grace Roepke, harp with CWRU Early Music Singers, ElenaPaul Hindemith Mullins, (1895–1963) director from Sonate für Harfe Sehr langsam Grace Cross ProgramCarlos Salzedo Chanson dans la nuit Grace Cross & Grace Roepke Kyrie from La Messe de Nostre Dame Guillaume de Machaut (ca.1300–77) Caroline Lizotte (b. 1969) from Suite Galactique, op. 39 Early Music Singers Exosphère Gracedirected Roepke by Elena Mullins Pierre Beauchant (1885–1961) Triptic Dance Douce dame Machaut Grace Cross & Grace Roepke Nathan Dougherty, voice withSylvius Medieval Leopold WeissEnsemble (1687–1750) from Lute Sonata no. 48 in F-sharp minor (arr. for guitar by A. Poxon) I. Allemande Lucas Saboya (b. 1980) from Suite Ernestina I. Costurera Quarte estampie royale II. DeAnonymous Algún Modo (Manuscrit du Roy) AllisonBuddy Johnson Monroe, (1915-1977) vielle • Karin Cuellar,Since rebec I Fell for You Laura(arr. for Osterlund, guitar by A. recorderPoxon) • Margaret Carpenter Haigh, harp Andy Poxon, guitar Agustín Barrios (1885–1944) Vals, op. 8, no. 4 Comment qu’a moy lonteinne Machaut J. S. Bach (1685–1750) from Sonata no. 3 in C major, BWV 1005 Margaret Carpenter Haigh, voice IV. Allegro assai Heitorwith ensemble Villa-Lobos (1887–1959) Etude no. 7 Year Yoon, guitar Portrait of Helen Sears, 1895. John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Oil on canvas; 167.3 x 91.4 cm. Museum of Fine(continued Arts, Boston Gift of Mrs. onJ. D. Cameron reverse) Bradley 55.1116. -

Troubadours NEW GROVE

Troubadours, trouvères. Lyric poets or poet-musicians of France in the 12th and 13th centuries. It is customary to describe as troubadours those poets who worked in the south of France and wrote in Provençal, the langue d’oc , whereas the trouvères worked in the north of France and wrote in French, the langue d’oil . I. Troubadour poetry 1. Introduction. The troubadours were the earliest and most significant exponents of the arts of music and poetry in medieval Western vernacular culture. Their influence spread throughout the Middle Ages and beyond into French (the trouvères, see §II below), German, Italian, Spanish, English and other European languages. The first centre of troubadour song seems to have been Poitiers, but the main area extended from the Atlantic coast south of Bordeaux in the west, to the Alps bordering on Italy in the east. There were also ‘schools’ of troubadours in northern Italy itself and in Catalonia. Their influence, of course, spread much more widely. Pillet and Carstens (1933) named 460 troubadours; about 2600 of their poems survive, with melodies for roughly one in ten. The principal troubadours include AIMERIC DE PEGUILHAN ( c1190–c1221), ARNAUT DANIEL ( fl c1180–95), ARNAUT DE MAREUIL ( fl c1195), BERNART DE VENTADORN ( fl c1147–70), BERTRAN DE BORN ( fl c1159–95; d 1215), Cerveri de Girona ( fl c1259–85), FOLQUET DE MARSEILLE ( fl c1178–95; d 1231), GAUCELM FAIDIT ( fl c1172–1203), GUILLAUME IX , Duke of Aquitaine (1071–1126), GIRAUT DE BORNELH ( fl c1162–99), GUIRAUT RIQUIER ( fl c1254–92), JAUFRE RUDEL ( fl c1125–48), MARCABRU ( fl c1130–49), PEIRE D ’ALVERNHE ( fl c1149–68; d 1215), PEIRE CARDENAL ( fl c1205–72), PEIRE VIDAL ( fl c1183–c1204), PEIROL ( c1188–c1222), RAIMBAUT D ’AURENGA ( c1147–73), RAIMBAUT DE VAQEIRAS ( fl c1180–1205), RAIMON DE MIRAVAL ( fl c1191–c1229) and Sordello ( fl c1220–69; d 1269).