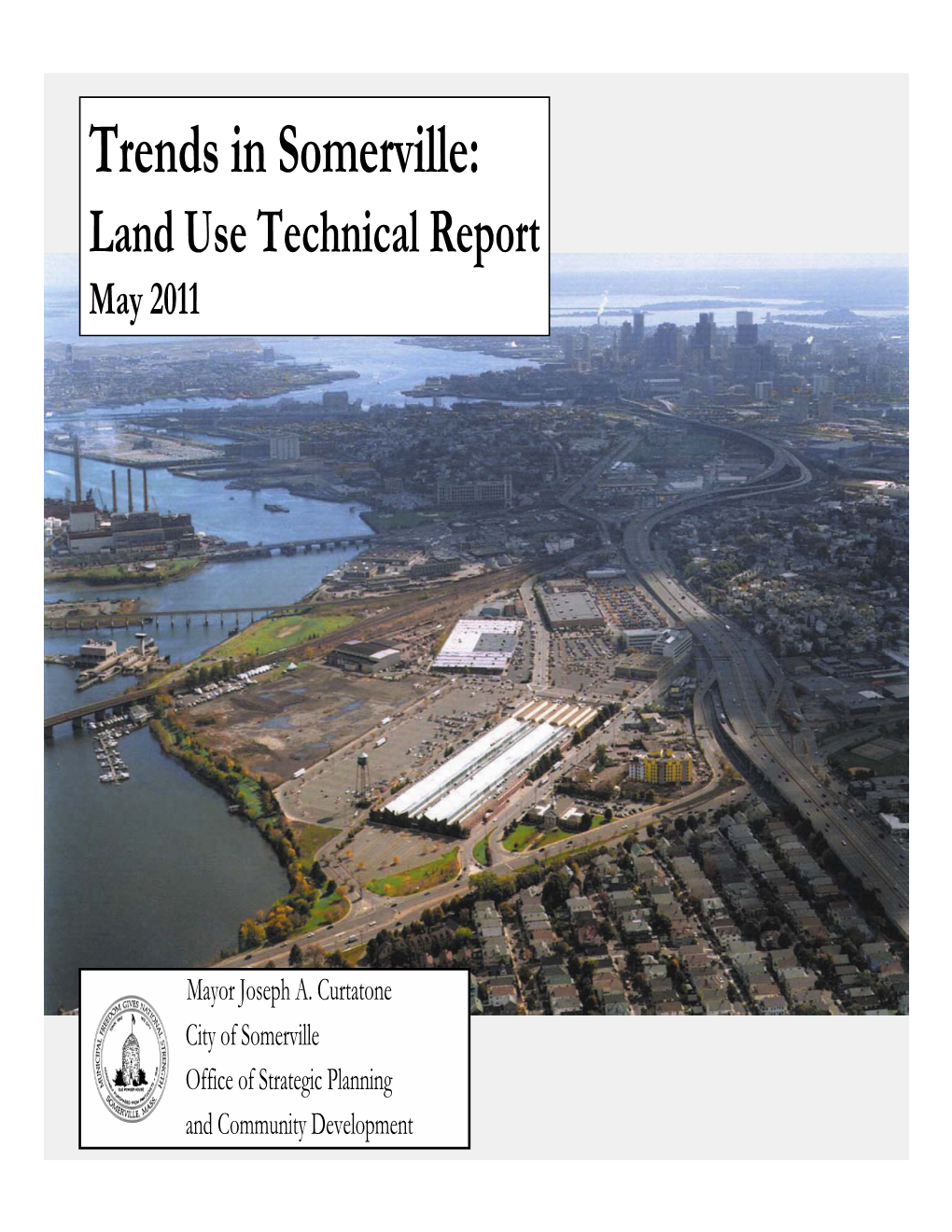

Landuse Trends Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restoration Plan and Environmental Assessment for the Industri-Plex Superfund Site Town of W Oburn, Middlesex County, Massachusetts

Rest oration Plan and Environmental Asses sment for the Industri-Plex Superfund Site Draft for Public Review February 19, 2020 Prepared by: Industri-Plex NRDAR Trustee Council Commonwealth of Massachusetts U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration With support from: Abt Associates 6130 Executive Boulevard Rockville, MD 20852 Abt Associates Report Title Insert Date ▌1-1 This page intentionally left blank Industri-Plex RP/EA February 19, 2020 ▌i CONTENTS CONTENTS List of Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. vi 1. Introduction to the Restoration Plan and Environmental Assessment ..................... 1 1.1. Trustee Responsibilities and Authorities ................................................................. 1 1.2. Summary of Industri-Plex NRDAR Settlement ........................................................ 2 1.3. Summary of Natural Resource Injuries ................................................................... 2 1.4. Purpose and Need for Restoration .......................................................................... 4 1.5. Restoration Goals ...................................................................................................4 1.6. Coordination and Scoping ....................................................................................... 4 -

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing Business Name City State Category 111 Chop House Worcester MA Restaurants 122 Diner Holden MA Restaurants 1369 Coffee House Cambridge MA Coffee 180FitGym Springfield MA Sports and Recreation 202 Liquors Holyoke MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 21st Amendment Boston MA Restaurants 25 Central Northampton MA Retail 2nd Street Baking Co Turners Falls MA Food and Beverage 3A Cafe Plymouth MA Restaurants 4 Bros Bistro West Yarmouth MA Restaurants 4 Family Charlemont MA Travel & Transportation 5 and 10 Antique Gallery Deerfield MA Retail 5 Star Supermarket Springfield MA Supermarkets and Groceries 7 B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7 Nana Japanese Steakhouse Worcester MA Restaurants 76 Discount Liquors Westfield MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 7a Foods West Tisbury MA Restaurants 7B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7th Wave Restaurant Rockport MA Restaurants 9 Tastes Cambridge MA Restaurants 90 Main Eatery Charlemont MA Restaurants 90 Meat Outlet Springfield MA Food and Beverage 906 Homwin Chinese Restaurant Springfield MA Restaurants 99 Nail Salon Milford MA Beauty and Spa A Child's Garden Northampton MA Retail A Cut Above Florist Chicopee MA Florists A Heart for Art Shelburne Falls MA Retail A J Tomaiolo Italian Restaurant Northborough MA Restaurants A J's Apollos Market Mattapan MA Convenience Stores A New Face Skin Care & Body Work Montague MA Beauty and Spa A Notch Above Northampton MA Services and Supplies A Street Liquors Hull MA Beer, Wine and Spirits A Taste of Vietnam Leominster MA Pizza A Turning Point Turners Falls MA Beauty and Spa A Valley Antiques Northampton MA Retail A. -

Metro Boston Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy - WORKING DRAFT

Metro Boston Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy - WORKING DRAFT - Funding provided by the Federal Sustainable Communities Program and the Barr Foundation Revised June 2015 By: Metropolitan Area Planning Council 60 Temple Place Boston, MA 02111 617.933.0700 www.mapc.org With assistance from: Tellus Institute 11 Arlington St. Boston, MA 02116 Acknowledgements This report was originally produced in June 2014 by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, and revised on June 1 , 2015 after discussion and approval by the MAPC Executive Committee. Technical assistance was provided by Martin Pillsbury, Environmental Director (Project Manager); Julie Conroy, Senior Environmental Planner (Primary Author); Sam Cleaves, Senior Regional Planner (Author); Bill Wang, GIS Analyst; and Barry Keppard, Public Health Division Manager; James Goldstein, Senior Fellow, Tellus Institute; and William Dougherty, President, Climate Change Research Group. Editing and continued guidance was provided by Marc Draisen, MAPC Executive Director. The Metro-Boston Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (RCCAS) was undertaken with funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Sustainable Communities Program and the Barr Foundation. We would also like to thank the MAPC Officers for their continued support: Lynn Duncan, President; Keith Bergman, Vice President; Shirronda Almeida, Secretary; and Taber Keally, Treasurer. Special appreciation goes to the members of the RCCAS Advisory Committee for their continuous assistance and leadership: John Bolduc Environmental Planner Cambridge Community Development Dept. Wayne Castonguay Executive Director Ipswich River Watershed Assoc. Hunt Durey Acting Director MA Dept. of Ecological Restoration Kwabena Kyei-Aboagye MA Urban Program Manager U.S. -

Hamersley's Bistro Fomu Brown Sugar Cafe Trident Booksellers & Cafe

Sweetgreen.com Wendy's Back Bay 659 Boylston St 551 BOYLSTON STREET, BOSTON, MA Boston MA 02116 (617) 262-0727 617-936-3464 Baked Potatoes, apples, Mon - Sun 10:30am - 11pm salad can customize hours variable Build your own & sides. 2 blocks from hotel 3.5 blocks from hotel Hamersley's Bistro Trident Booksellers & Cafe Travelers' Choice® 2012 Winner Restaurants Ranked #278 of 2,668 in Boston Ranked #37 of 2,668 in Boston 112 reviews 201 reviews “Quaint” 06/12/2013 “Is the Price:Value Quotient Really “great for brunch” 06/07/2013 The...”06/11/2013 Price: $20 “Great Bistro Fare” 06/10/2013 Cuisines: Vegetarian, Café Price: $41 - $80 Map | Visitor photos (7) | Menu Cuisines: American, Mediterranean, Seafood, Vegetarian, Bistro Map | Visitor photos (13) | Menu Chilli Duck Ranked #282 of 2,668 in Boston FoMu 54 reviews Ranked #95 of 2,668 in Boston “Low key dinner” 06/03/2013 6 reviews “Great Thai place!” 05/26/2013 “Real ice cream for people with Price: $21 - $30 allergi...”06/05/2013 Cuisines: Asian, Thai, Vegetarian “A terrific surprise” 04/28/2013 Map | Visitor photos (1) | Menu Cuisines: Vegan Map | Visitor photos (1) Max and Dylans Ranked #287 of 2,668 in Boston Brown Sugar Cafe 57 reviews Ranked #237 of 2,668 in Boston “Brits in Boston” 06/12/2013 74 reviews “Short notice but very accomodating”05/14/2013 “Consistently good food and a step Price: $20 - $25 abov...”05/11/2013 Cuisines: American, Vegetarian, Bar, “Great Thai Food” 05/06/2013 Sandwiches Price: $20 Map | Visitor photos (6) | Menu Cuisines: Thai, Vegetarian, Vietnamese, -

Section 16 - ABP Progress & Expenditures Report, Run Date: 12/15/2015 10:08:00 AM Page 1 of 13 ESTIMATED COSTEXPENDITURES ESTIMATED SCHEDULE

ABP Progress and Expenditures Report Pursuant to 2008 Transportation Bond Act Chapter 233 §16 Data is current through 11/15/2015 This progress and expenditure report contains project expenditures incurred as of August 4, 2008 through the report date. This report may not reflect total project cost if the project incurred expenditures prior to August 4, 2008. Column Header Footnotes: 1 PRELIMINARY ESTIMATE - The preliminary estimate is not a performance measure for on-budget project delivery. It is the estimated construction cost value that was included in the November 30, 2008 report to the Legislature pursuant to §19 of Chapter 233 of the Acts of 2008; used for early budgeting purposes only. This “baseline” estimate was established at the inception of the program before many projects were scoped. This estimate included allowances for incidentals for construction such as police details, adjustment for inflation, and reasonable contingencies to account for growth approved by MassHighway/DCR. The Preliminary Estimate did NOT include costs associated with design, right-of-way, force accounts, project oversight, or other program related costs. * Indicates project is one of several that had an incorrect “Preliminary Estimate” and/or scheduled completion, as part of the Chapter 233 §19 Legislative requirement, to provide the estimates and schedules, as part of the 3 year plan of ABP. This Project had actual bid amounts and encumbered amounts, at the time of the filing of the Dec‐08 Legislative Report, but was not properly accounted for in the recording of the Dec‐08 Legislative Report. The Nov/Dec‐08 Conceptual Plan Chapter 233 §19 "Construct Cost" and/or "Completion" in this report reflect the corrected values as approved by the ABP Oversight Council at the March 8, 2010 Quarterly Meeting. -

AUGUST 19, 2020 TWENTY-FIVE CENTS Inside: Somerville Moves Towards Prioritizing Buses, Bikes and Pedestrians

VOL. 8 NO. 33 SOMERVILLE, MASS. WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 19, 2020 TWENTY-FIVE CENTS Inside: Somerville moves towards prioritizing buses, bikes and pedestrians By Denise Keniston On Thursday, August 10, Somerville’s Trans- portation Mobility Planners held their second public meeting on the “Holland St. and Col- lege Ave. Mobility Improvements” project. In Spring 2021, the city will start resurfacing the roadways and sidewalks of Holland Street from Davis Street to Teele Square, and of Col- lege Avenue, from Davis Square to Powder No mask, House Circle. no service The project focuses on prioritizing buses, page 3 bikes, and pedestrians with shared bus/bike lanes and other new surface roadway layouts and pavement markings. Justin Schreiber is a Transportation Mobility Department Plan- ner. He says public input has been essential in the design phase. Fall 2019 - Broadway after bus/bike lane restriping. The Holland St. and College Ave. plan will claim rush hour “At different points on Holland St. and Col- parking spots to be used as bus/bike only lanes. — Photo courtesy of Kittelson and Associates lege Avenue on-street parking Continued on page 4 Cambridge Health Alliance unveils 'Care to the People' mural Sustainable energy By Isabel Sami for Somerville To brighten and incite joy in Somerville, the page 5 Cambridge Health Alliance Foundation had an idea: a beautiful mural at the CHA Somerville Campus. Together with the Somerville Arts Council, the foundation put out a call for local artists to submit ideas for the mural, and Aman- da Hill was selected. On Thursday, August 13, the “Care to the Peo- ple” mural was unveiled. -

DCR's Beaver Brook Reservation

Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Bureau of Planning and Resource Protection Resource Management Planning Program RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN DCR’s Beaver Brook Reservation Historic Beaver Brook Reservation and Beaver Brook North Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts March 2010 DCR’s Beaver Brook Reservation Historic Beaver Brook Reservation and Beaver Brook North Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2010 Deval L. Patrick, Governor Timothy P. Murray, Lt. Governor Ian A. Bowles, Secretary Richard K. Sullivan, Jr., Commissioner Jack Murray, Deputy Commissioner for Parks Operations The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), an agency of the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, oversees 450,000 acres of parks and forests, beaches, bike trails, watersheds, dams, and parkways. Led by Commissioner Richard K. Sullivan Jr., the agency’s mission is to protect, promote, and enhance our common wealth of natural, cultural, and recreational resources. To learn more about DCR, our facilities, and our programs, please visit www.mass.gov/dcr. Contact us at [email protected]. Printed on Recycled Paper RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN Expanded Beaver Brook Reservation Belmont, Lexington and Waltham, Massachusetts Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 1 Planning Process 2 Distinctive Characteristics of the Expanded Reservation 2 Priority Findings 3 Recommendations 5 Capital Improvements 7 Land Stewardship Zoning Guidelines 9 Management -

Solar Electricity Pricing Plans Debated

Belmont Citizens Forum Solar Electricity Pricing Plans Debated By Meg Muckenhoupt and Virginia Jordan with an annual cap on solar buyback of 2% of total system sales. When a homeowner’s roof-top solar panels Under Phase 1 net metering, to calculate the generate more electricity than needed, how monthly bill, Belmont Light would measure much should Belmont Light pay for the excess the total amount of electricity a household energy fed back to the grid? uses and then subtract the electricity the That question is roiling environmental circles household produces. If Mary and Bob Sunshine in Belmont. Cutting the payback makes it less use 100-kilowatt hours (kWh) in a month and likely for people to install solar panels. But, are their photovoltaic solar panel system produced ratepayers subsidizing solar power, or vice versa, 75 kWh hours, they would be billed simply for and if so, by how much? Concerned residents 25 kWh. On the other hand, if their system can comment at the Belmont Light public produced 125 kWh, they would be billed hearing on September 18, 2014, at the Town Hall nothing that month and credited 25 kWh Auditorium, 455 Concord Avenue. against future use. Background The retail cost of electricity to Belmont residents includes the wholesale cost plus In 2008, Massachusetts mandated that overhead. Wholesale is what Belmont Light utilities adopt new net metering incentives pays to energy providers; it appears on your to encourage renewable energy installations. electric bill as Generation Usage. Overhead “Renewable energy” means solar, wind, or other includes maintenance of distribution lines non-fossil-fuel. -

Evaluation of Groundwater Flow and Contaminant Transport

EVALUATION OF GROUNDWATER FLOW AND CONTAMINANT TRANSPORT AT THE WELLS G&H SUPERFUND SITE, WOBURN, MASSACHUSETTS, FROM 1960 TO 1986 AND ESTIMATION OF TCE AND PCE CONCENTRATIONS DELIVERED TO WOBURN RESIDENCES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree, Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Maura A. Metheny, B.S., M.S. The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Professor E. Scott Bair, Advisor Assistant Professor Anne Carey Approved by Professor Carolyn Merry ______________________________ Professor Franklin Schwartz Advisor Department of Geological Sciences Copyright by Maura A. Metheny 2004 ABSTRACT Contamination of municipal wells G and H was discovered in 1979 and was statistically linked by epidemiological studies to leukemia cases that occurred in Woburn, Massachusetts in the late 1960’s through the early 1980’s. Historical contamination of the buried valley aquifer at the 133 hectare Wells G&H Superfund Site is simulated using MT3D-HMOC code to determine the possible contamination history of the wells with TCE and PCE. A MODFLOW groundwater flow model calibrated using measured heads, measured streamflow gains and losses, and tritium/helium-3 groundwater ages was used to compute flow velocities. The 26-year transient groundwater flow model incorporates realistic pumping schedules and variable recharge rates. Although the wells operated from 1964 to 1979, the transport model spans the period 1960 to 1985 so that the simulated concentrations can be compared to water quality measurements from 1979 through 1985. At least five local sources contributed TCE, PCE, and other contaminants to the groundwater system. The precise contaminant release times and source concentrations are not known for the sites. -

City of Somerville, Massachusetts Mayor’S Office of Strategic Planning & Community Development Joseph A

CITY OF SOMERVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS MAYOR’S OFFICE OF STRATEGIC PLANNING & COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT JOSEPH A. CURTATONE MAYOR MICHAEL F. GLAVIN EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION DETERMINATION OF SIGNIFICANCE STAFF REPORT Site: 151 Linwood Street Case: HPC 2018.100 Applicant Name: AREC 8, LLC Date of Application: September 6, 2018 Recommendation: NOT Significant Hearing Date: October 16, 2018 I. Historical Association Historical Context: “The trucking industry in the United States has affected the political and economic history of the United States in the 20th century. Before the invention of automobiles, most freight was moved by train or horse-drawn vehicle. “During World War I, the military was the first to use trucks extensively. With the increased construction of paved roads, trucking began to achieve significant foothold in the 1930s, and soon became subject to various government regulations (such as the hours of service). During the late 1950s and 1960s, trucking was accelerated by the construction of the Interstate Highway System, an extensive network of freeways linking major cities across the continent.”1 1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_trucking_industry_in_the_United_States accessed 10/5/2018 CITY HALL ● 93 HIGHLAND AVENUE ● SOMERVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS 02143 (617) 625-6600 EXT. 2500 ● TTY: (617) 666-0001 ● FAX: (617) 625-0722 www.somervillema.gov Page 2 of 15 Date: October 16, 2018 Case: HPC 2018.100 Site: 151 Linwood Street Evolution of Site: taken from the NR Nomination Form for 1 Fitchburg Street Development of the Brick Bottom Neighborhood “(T)he streets of the adjacent Brick Bottom neighborhood were determined at a much earlier date. In June of 1857, the Boston & Lowell Railroad hired William Edson, "delineator" of the J.H. -

B&MRRHS Display Case Collection 2021

Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Incorporated Assortment of railroad artifacts have now been preserved in display cases purchased by the society in 2018 16.5”x 12.5” Display cases Boston & Maine Railroad China Place Setting Feb 21, 1932 Menu B&MRR Snow Train Anonymous Donor Boston & Maine Railroad Assortment Conductor & Trainman Badges B&M Railroad Police Patch B&M Baggage Checks B&M Pins & Uniform Buttons Fitchburg Conductor & Brakeman Hat Badges. B&M Lighter, Ticket Puncher. Anonymous Donor Boston & Maine Railroad Brass Conductor Badges Brass Uniform Pins From the collection of former B&MRR Conductor Arthur E. Paquette Donation by; Mr. David C. Paquette Boston & Maine Railroad Silver Trainman Badges Silver Trainman Uniform Pins and Belt Buckles From the collection of former B&MRR Trainman Arthur E. Paquette Donation by; Mr. David C. Paquette Boston & Maine Railroad Assortment B&M Belt Buckles B&M Uniform Buttons B&M Brass Conductor Hat Badge PRR Belt Buckle, A.E.P. Belt Buckle United Transportation Works Union Lapel Pins. Donation by; Mr. David C. Paquette Boston & Maine Railroad Police Badges President Police Badge 2 Officers Police Badges 11 Police Badges Donation by; Mr. Alan Dustin Boston & Maine Railroad Station Agent – Telegrapher 25 & 50 Years Award Pins Photo Lowell B&M Station Photo Mr. Stanley E. Champeau Railroad Pass Cards 1928 New York Central Railroad 1927 Central Railroad Co. of New Jersey 1957 Boston & Maine Railroad No. 12902 1957 Boston & Maine Railroad No. 27419 Donation by; Ms. Belinda Champeau Boston & Maine Railroad Award Letter Mr. Stanley E. Champeau 50 Years of Service North Station, Boston, Mass Feb 29, 1968 Donation by; Ms. -

Transportation & Infrastructure Presentation

Trends in Somerville: Transportation & Infrastructure Report September 2009 Mayor Joseph A. Curtatone City of Somerville Office of Strategic Planning and Community Development Transportation & Infrastructure Trends Report City of Somerville Comprehensive Plan Report Introduction Technical Report #3 I. REPORT INTRODUCTION use in Somerville declined by roughly 20% during the approximate same time period. The City of Somerville depends upon its infrastructure which • The majority of Somerville’s home heating comes from utility provides the fundamental systems needed for residents to undertake gas (62%), significantly more than many of its neighboring their daily routines and employment, for businesses to thrive, and cities: Boston (48%), Brookline (41%), Cambridge (63%), new development to proceed. The transportation network within Chelsea (41%), Everett (50%), and Medford (43%). Somerville allows the population to be mobile and brings people and • Due to the commuter and freight rail lines that run through business into and out of the city. The history and patterns of the city much of Somerville is divided, or connected, by development for both the transportation and infrastructure network bridges. affects the City’s ability to reach economic development and land use • Somerville has made significant investments in its roadways – goals. By understanding the historical patterns and current paving 100 streets in the last four years and completing four capabilities and functionalities of these systems, and comparing our major road reconstruction projects. current conditions with surrounding communities, Somerville can • Somerville's public urban forest comprises over 11,000 better prepare itself to meet future demands and desires. trees, which provide an estimated $16 million in annual ecological, economic, and social benefits to the city.